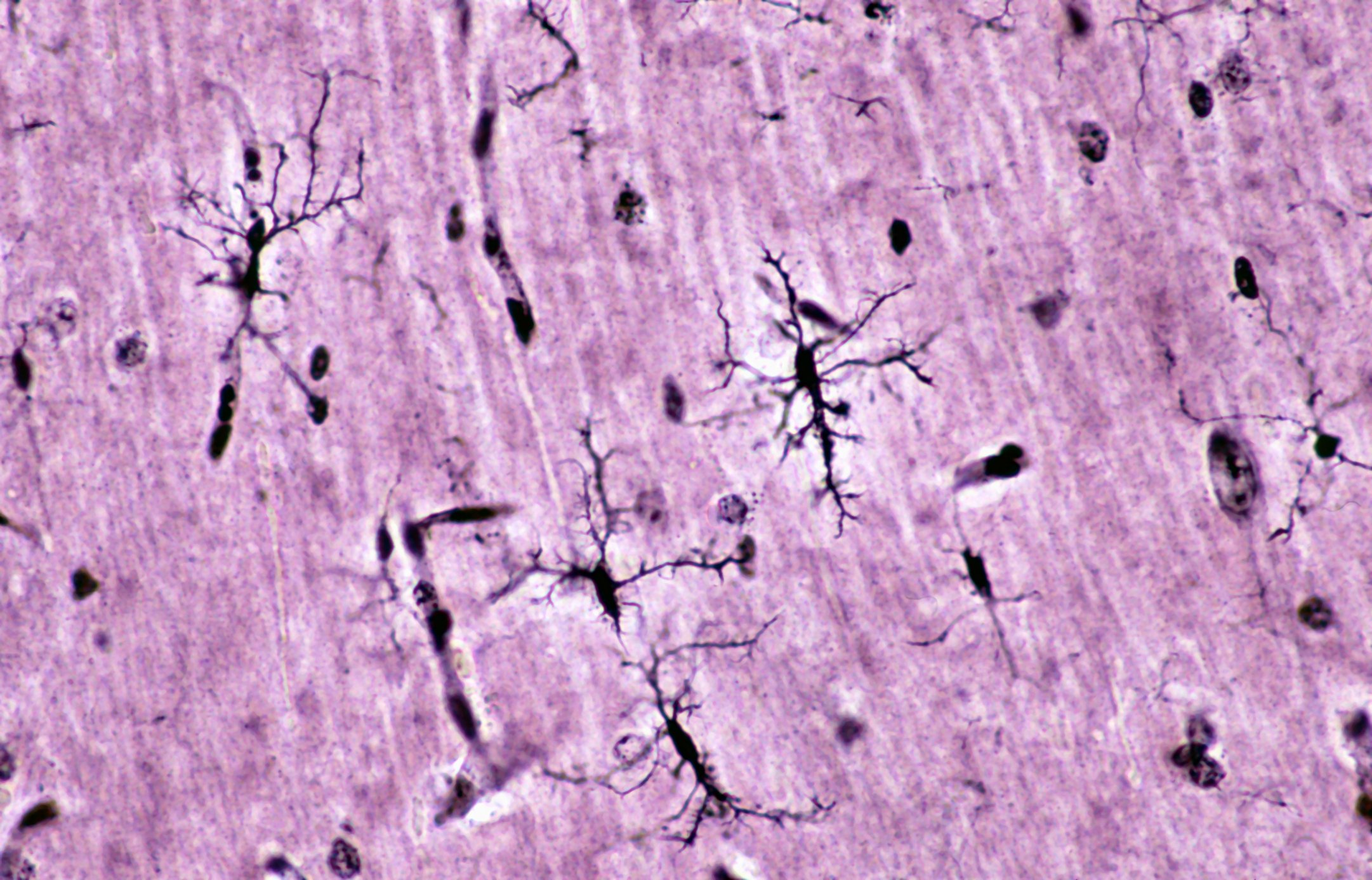

GP support for the patient and their relatives/carers is crucial to ensure the best possible course of the disease. Pharmacotherapy is only one component in the integral and multifactorial management of dementia. The factors of polymedication and individual benefit-risk profiles should always be included in the treatment concept. Regarding the use of traditional and modern antidementia drugs such as cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine or ginkgo extract, there are some new findings.

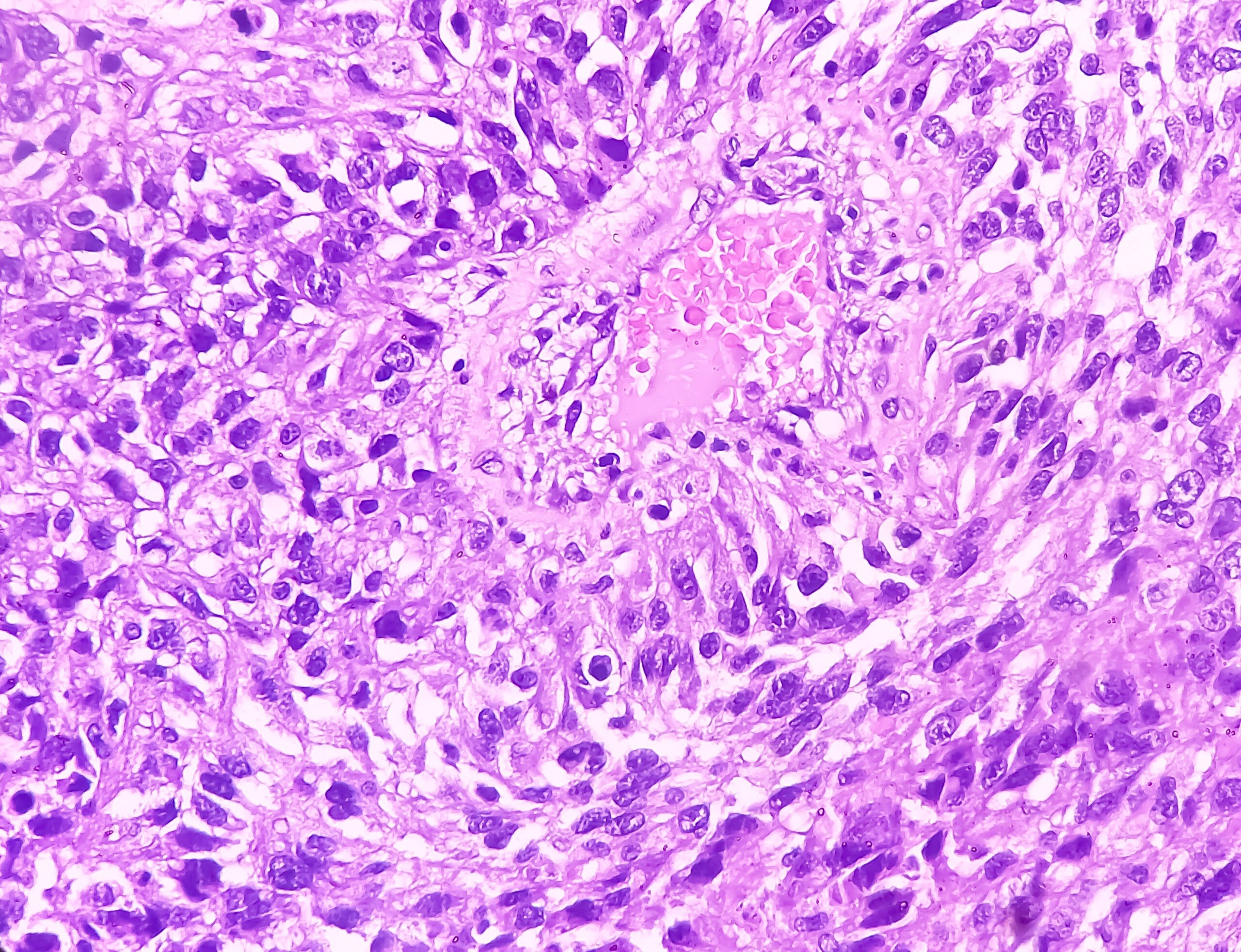

Despite huge financial investments by the pharmaceutical industry, there is still no curative dementia therapy in sight. After the numerous setbacks in therapy development in the amyloid field, the breadth of research approaches had to be opened up further. In addition to immunotherapy with tau antibodies (tau as the second typical deposit besides amyloid in Alzheimer’s dementia), other innovative approaches, such as anti-inflammatory therapy via targeted modification of the intestinal flora, are also being scientifically tested.

Cognitive disorders in old age are common and can – if diagnosed early and correctly – probably not be cured with currently available drug and non-drug measures, but they can be influenced positively in a decisive way. Both the assessment and the therapy are tailored to the individual patient and depend to a large extent on the patient’s consent, state of health and social circumstances.

Introduction

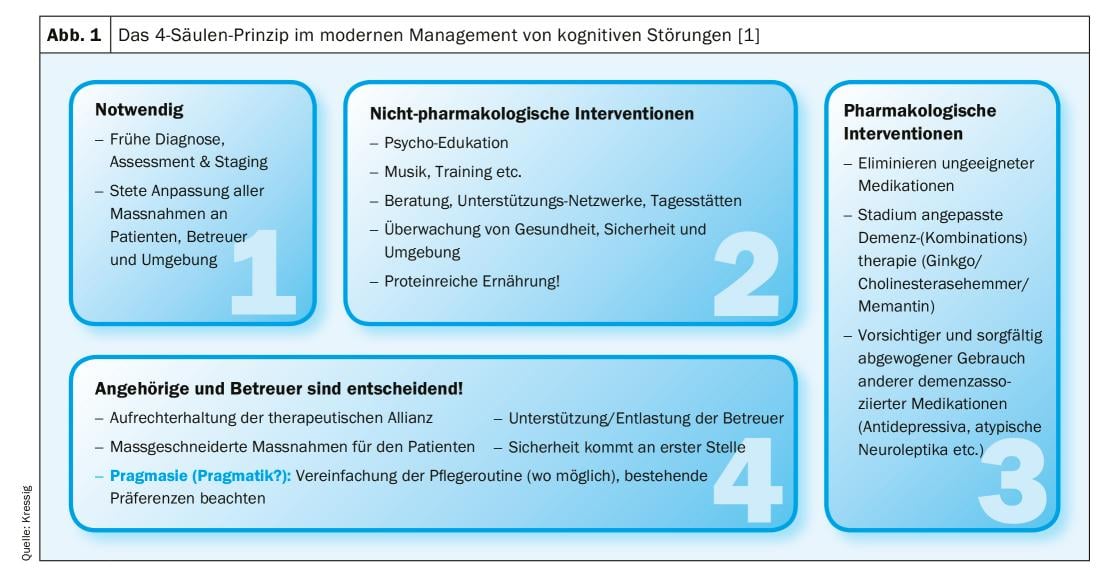

We can deal with patient complaints of cognitive impairment in younger adults, but more specifically in the 3. and 4th age are confronted. In any case, such complaints must be taken seriously, because if the diagnosis is made correctly and therapeutic measures are initiated at an early stage, the further course of the disease can be changed significantly. Although since the introduction of the DSM-5 the term “dementia” actually no longer exists and one now only speaks of “severe neurocognitive disorders”, this clinical picture, which is common in old age (one in three over 85-year-olds is affected!), has of course not disappeared. Although the incidence of dementia has decreased by up to 50% over the past 20 years as a result of significantly improved treatment of vascular risk factors – demographic change has virtually neutralized this medical progress in numerical terms. The modern management of cognitive disorders in dementia development is based on 4 pillars (Fig. 1) : Early and precise diagnosis, drug therapy, non-drug therapy measures, and targeted support/guidance of relatives and caregivers [1].

Are there “normal” cognitive disorders in old age?

Patients – like us doctors – have a tendency to blame aging or age in general for increased forgetfulness and other “minor” brain malfunctions. The fact is another. Normal brain aging is very well studied scientifically and is associated only with a discrete slowing of thought and reaction processes. So if a name cannot be remembered immediately, but after a certain time, this is still “normal”. If you have always had a poor memory for names, you should not expect any improvement in this regard as you get older! However, if the forgetfulness is new and the resulting subjective distress of the patients is present (even in neuropsychological examination with normal findings), then according to the latest findings, this should be considered as “Subjective Cognitive Decline”, which leads to dementia in 25% of cases within 6 years [2]. Unfortunately, brain disorders are still reduced by many primarily to memory and forgetfulness. However, our brain does much more! Many dementia processes begin in other brain areas where deterioration (while memory is preserved) becomes apparent primarily through different behavior (e.g., more problems with complex tasks such as managing financial matters or even cooking more complicated menus!). Such changes are not normal and must be clarified!

Demarcation of “normal” versus “pathological

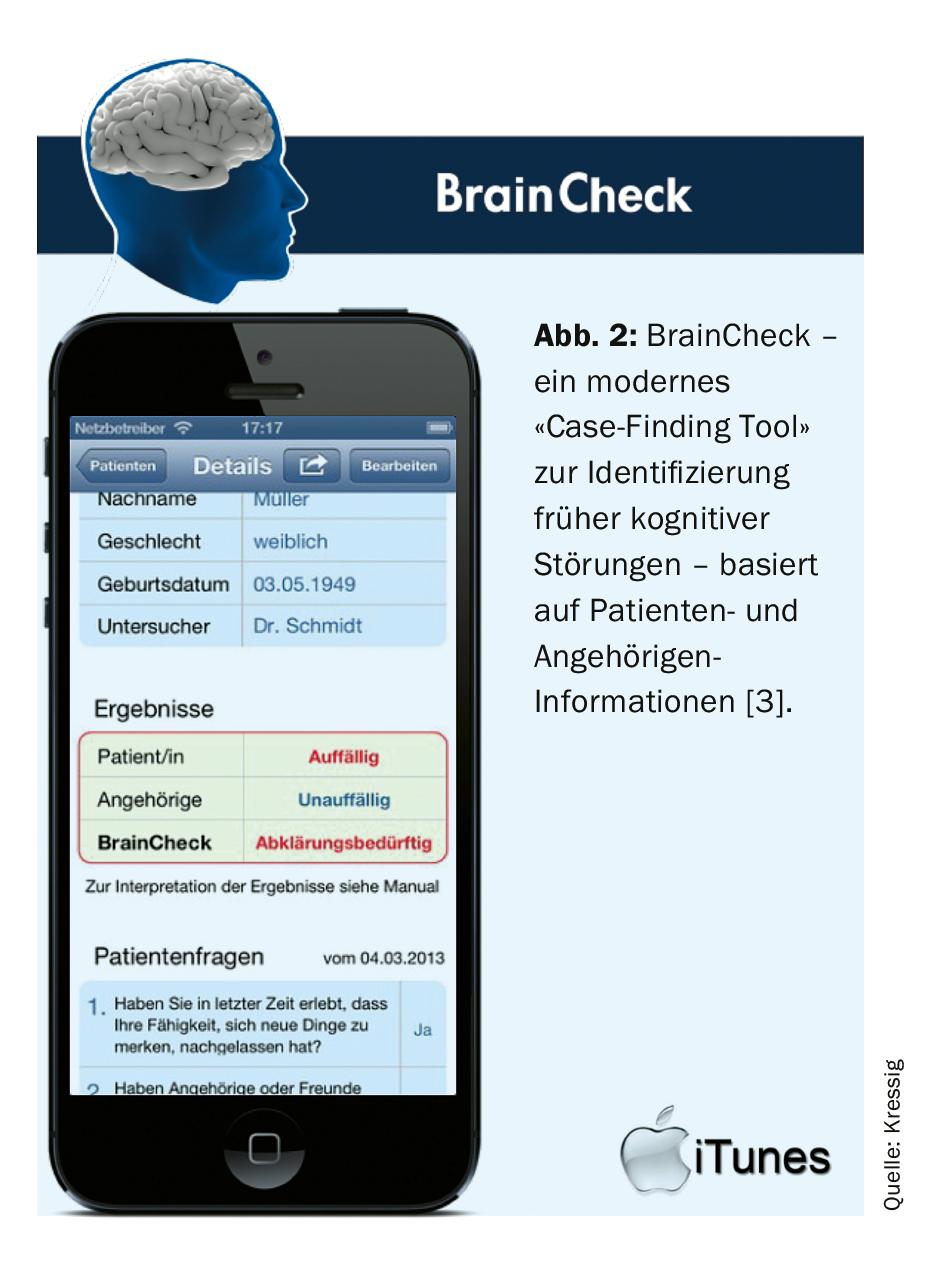

In everyday practice, it must be possible to decide quickly and with little time expenditure whether cognitive disorders need to be clarified further quickly, whether further observation is necessary or whether no further action is required! The former (time-consuming) screening of cognitive disorders by means of MMSE and clock test has been replaced in recent years by the more sensitive and targeted “case finding” by means of “app (Fig. 2). The paid app “BrainCheck” developed by the “Swiss Memory Clinics” and Swiss general practitioners separates “normal” from “pathological” in a few minutes with a discriminatory power of 90% [3]! To do this, the patient must answer three simple questions and complete a watch test. At the same time, his closest relative/partner is asked 7 short questions. All results can be recorded and assessed immediately in the app. The brief assessment can be easily integrated into the electronic medical record as a PDF file.

In addition to purely cognitive abnormalities, other clinical symptoms such as weight loss, behavioral changes, or depressive mood may also reinforce the early suspicion of dementia development.

If further clarification is required, a decision must be made together with the patient and his or her relatives on how to proceed with the diagnosis. As a first step, the (simple) exclusion of quickly treatable causes is certainly an absolute “must” here. A thyroid disorder can be ruled out by means of TSH determination, depression can be detected by means of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and a psychosocial stress situation (stress load) can be detected with a careful anamnesis and, in the positive case, addressed with appropriate countermeasures. In the case of anamnestically justifiable suspicion, a vitamin B status and lues serology can also be of further assistance. If one finds in the mentioned areas and is accordingly therapy-active, it is recommended to follow-up the cognition about 6 months later by means of BrainCheck.

Cognitive disorders requiring clarification

The type of further workup for cognitive impairment is highly individualized and depends on the patient’s consent, health status/life expectancy, and social circumstances. Younger and fitter seniors should always seek specialized evaluation from a dementia specialist or memory clinic. In addition to a medical examination with laboratory and biomarkers, this includes a neuropsychological assessment with brain imaging (MRI). In very elderly and fragile patients, an abbreviated cognitive assessment (e.g., using MoCa assessment [4]) can also be performed. This can – with some experience – be performed and diagnostically evaluated in the general practitioner’s office. Again, this imperatively includes brain imaging (MRI or CT) to determine the most likely neuropathologic cause of dementia development. This is crucial for the type of therapy to be initiated.

Cognitive disorders: Therapeutic options

If these are “mild” cognitive disorders according to the DSM-5, they are within two standard variations of a normal cognitive finding. Therapeutic options here include medicinal (Ginkgo Biloba 240 mg/d and vitamin D 24,000 units per month), the main focus is on non-drug measures: regular physical and social (cognitive) activity, a healthy age-appropriate diet (regular and sufficient protein – at least 1.2 g/kg body weight per day; Mediterranean diet with sufficient omega-3 acids) and good GP control of vascular risk factors (type of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia). In the Finnish FINGER study [5], significant cognitive improvements were achieved after 2 years with these lifestyle measures alone.

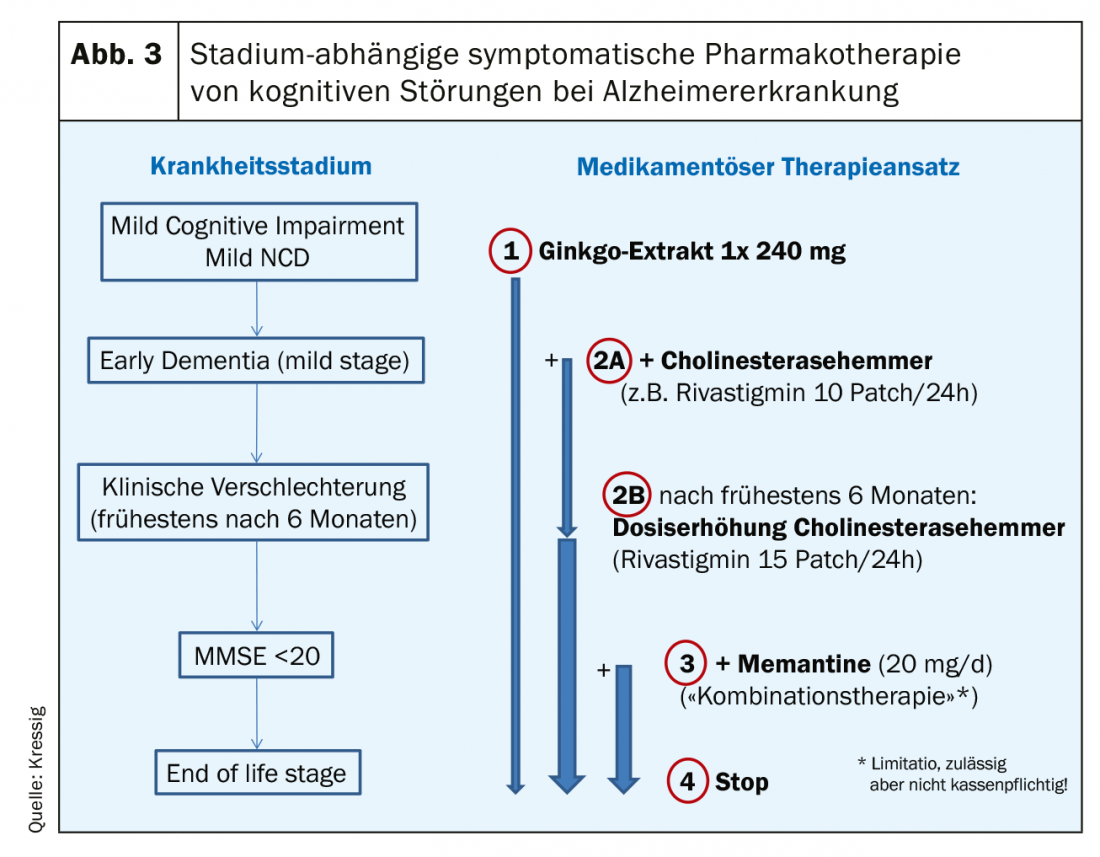

Drug options: Before new medications are used, it is essential to review any existing polypharmacy for cognitively impairing anticholinergic agents. If the disorder is a “majore” cognitive disorder (dementia) according to the DSM-5, the neuropathology underlying the process is critical in determining drug therapy. For this purpose, appropriate imaging with or without biomarkers is usually mandatory. If it is a neurodegenerative process (Alzheimer’s disease), ginkgo, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine are the first choice, depending on the stage (Fig. 3).

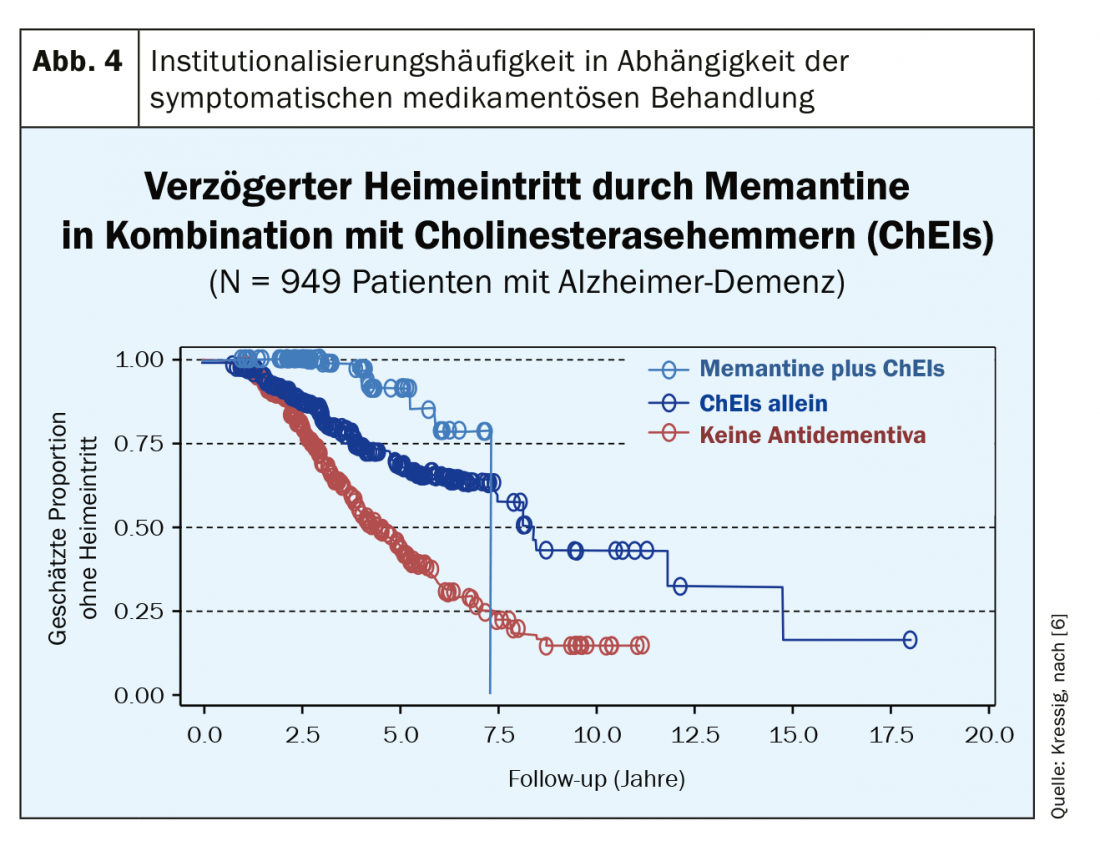

After more than 20 years of experience with these symptomatic therapy options, it has become clear that it is not the improvement of purely cognitive functions (e.g., memory) that makes the difference here to no drug treatment. This symptomatic therapy (if started early) significantly improves the course of the disease in terms of maintaining functionality and independence. These drugs are decidedly slow-acting, but have a high responder rate thanks to a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of less than 10 (for all three drug classes!). Compared to non-treated control populations, however, the first clinically noticeable differences appear only after one year of treatment; however, these become very relevant in the further years, since treatment leads to impressively fewer nursing home admissions (Fig. 4) [6]. The combination therapy of memantine with cholinesterase inhibitors (at MMSE <20) has proven to be very successful. In Switzerland, however, this is only possible off-label and is not fully covered by basic insurance due to a limitatio. Nevertheless, many patients are happy to pay the few hundred francs per year themselves (in view of the sharp drop in the price of anti-dementia drugs) if this saves the much higher financial costs of institutionalization. In addition to the longer preservation of everyday functionality with antidementia drugs, significantly fewer dementia-associated behavioral abnormalities (aggression, crying, motor restlessness, etc.) occur with this therapy.

If the underlying pathology of dementia is purely vascular, the above antidementia drugs (except ginkgo) are not effective and accordingly not indicated. Here, the goal is to slow further progression of the disease by all means possible, with lifestyle measures and control of vascular risk factors. Antidementia drugs can be used for mixed vascular-neurodegenerative forms of dementia. For rarer dementia pathologies such as Lewis-Body disease, Parkinson’s disease, or frontotemporal dementia, it is worth consulting with appropriate specialists.

Non-drug options: Non-drug interventions for dementia patients are recommended by major professional societies and expert groups primarily and as the primary approach for dementia-associated psycho-social behavioral disorders (BPSD), except in emergency situations [7]. According to Cohen-Mansfield [8], most physicians are trained and educated to prescribe medication for BPSD, but very few have knowledge of related non-drug therapeutic interventions and their effectiveness. Accordingly, antipsychotic medications are frequently used before nonpharmacologic interventions are attempted.

In contrast to the cognitive abilities that are impaired or lost early in dementia, emotional and psychosocial skills are often far less affected by deterioration until late stages of dementia. This is where non-drug interventions come in, by accessing existing brain performance resources – away from the deficit focus – and using and promoting them in a targeted manner. Physical activity, music-based activities, and high-protein diets supplemented with vitamin D to maintain muscle health in dementia have been shown to be most successful [9]. Exciting and always the subject of research is the brain effect of movement activities combined with music, such as dance and rhythmics. In the “Einstein Aging” cohort study, regular dancing as a recreational activity was associated with up to 80% decreased risk of dementia later in life [10]. In an intervention study using rhythmics according to Dalcroze, the motor-cognitive dual-task ability of seniors living at home was improved and the risk of falls was reduced by over 50% [11]. In advanced stages of dementia, Dalcroze rhythmicity appears to promote language skills in particular, in addition to positively affecting BPSD symptoms [12].

Non-pharmacological interventions for dementia patients are an essential component of modern 4-pillar dementia management. The main expected effect of such measures is to positively influence BPSD without side effects. Physical activity programs show additional benefits for everyday functioning, which can be maintained significantly longer, especially with a concurrent high-protein diet and vitamin D supplementation. The daily protein requirement of at least 1.2 g protein per kg body weight to maintain muscle health in dementia can often only be achieved by using protein drink supplements. These are covered by the basic insurance upon approval of the costs (http://geskes.ch, “Home Care”) and can be delivered to the patient’s home. Music and music-based movement programs such as dance and rhythmics seem to be particularly suitable for mobilizing brain reserves and thus significantly improving cognition.

Conclusion for practice

Non-drug and drug symptomatic therapy for cognitive impairment is only one component in the multifactorial 4-pillar management of dementia. Non-drug approaches show marginal to no detectable cognitive effects, but are effective for behavioral problems, psychiatric symptoms, and caregiver burden. In pharmacological therapy, it is important to reduce existing polymedication as much as possible and to discontinue potentially harmful substances (Priscus list). At present, there are no rational reasons not to use the symptomatic antidementia drugs available today (cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, and ginkgo extract). Although the immediate clinical effects at the start of therapy are relatively small, the main advantages are in the long-term course (institutionalization delayed by years, significantly fewer behavioral disorders).

Take-Home Messages

- Pharmacopia is only one component in the integral and multifactorial management of dementia.

- In addition to early diagnosis, the primary care physician’s support of the patient and his/her relatives/caregivers is essential for the best possible course of the disease.

- In pharmacological therapy, the primary goal is to reduce existing polymedication and discontinue potentially harmful (anticholinergic) substances (Priscus list).

- At the present time, there are no rational reasons not to use the symptomatic antidementia drugs (cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, and standardized ginkgo extract) that have been available for years.

- Internationally, the combination of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in the approved MMSE range, as well as Ginkgo Biloba adjunctive therapy, is now state of the art in Alzheimer’s dementia therapy.

- In long-term studies, the combination therapy (cholinesterase inhibitor + memantine), which is only available off-label in Switzerland, delayed institutionalization by years and significantly reduced behavioral disorders.

Literature:

- Kressig RW: Dementia of the Alzheimer type: non-drug and drug therapy. Ther Umsch 2015; 72(4): 233-238.

- Wolfsgruber S, et al: Differential Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia in Stable Versus Unstable Patterns of Subjective Cognitive Decline. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 54: 1135-1146.

- Ehrensperger M, et al: BrainCheck – a very brief tool to detect incipient cognitive decline: optimized case-finding combining patient- and informant-based data. Alz Res Ther 2014; 6: 69.

- Nasreddine, et al: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 695-699.

- Kivipelto M, et al: The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2013; 9: 657-665.

- Lopez OL, et al: Long-term effects of the concomitant use of memantine with cholinesterase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80: 600-607.

- Savaskan E, et al: Recommendations for diagnosis and therapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD). Praxis (Bern 1994) 2014; 103(3): 135-148.

- Cohen-Mansfield J: Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9: 361-381.

- Kressig RW: Non-drug treatment options in dementia. Internal Medicine Practice 2017; 58: 1-7.

- Verghese J, et al: Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2508-2516.

- Trombetti A, et al: Effect of music-based multitask training on gait, balance, and fall risk in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171(6): 525-533.

- Winkelmann A, et al.: La rythmique Jaques-Dalcroze: Une activité physique novatrice pour les personnes âgées. GERIATRIE PRATIQUE 2005; 3: 1-5.

GP PRACTICE 2020: 15(5): 16-19