During operations, it is not possible to achieve absolute sterility despite optimal hygiene measures. Thus, postoperative wound infections are a relevant clinical problem even today despite antiseptic techniques. In addition to pre- and perioperative measures, some principles must also be taken into account following a surgical procedure.

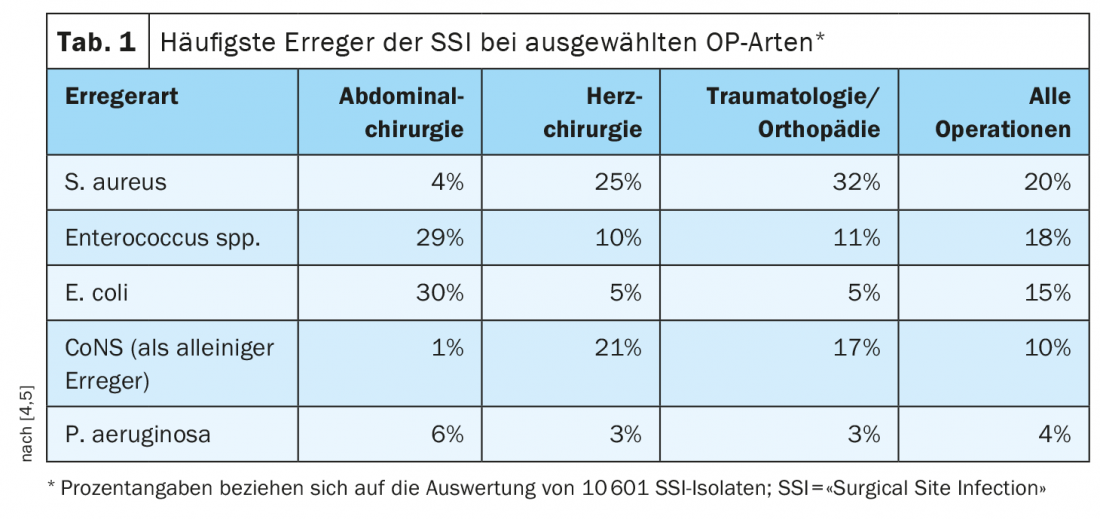

About 6% of patients in Swiss hospitals contract an infection [1]. This rate is in the European midfield. Wound infections after surgical procedures and catheter-associated bacteremia (blood poisoning) are particularly common and potentially serious. However, the lungs and urinary tract are also susceptible to infections after a medical procedure. “Surgical Site Infections” (SSI) result in longer hospital stays, higher costs and, in the worst cases, deaths. It is a serious and common complication of modern surgery with negative consequences for affected individuals and the healthcare system. The most important factors influencing SSI are, on the one hand, the general condition of the patient and, on the other hand, the type of surgery to be performed. Nosocomial postoperative wound infections are primarily caused by bacterial pathogens, rarely combined with fungi. The spectrum of pathogens varies depending on the type and location of surgery [3]. Certain facultative pathogens (e.g., coagulase-negative staphylococci, CoNS) occur only in special constellations, for example, in connection with implants. Table 1 provides an overview of the empirically identified most important pathogen species [4]. Postoperatively, it is particularly important to avoid secondary colonization of wounds that are still open and/or drains that are in place, as well as contamination of other patients. However, attempts to subsequently antisepticize the wound or the wound environment usually have no effect on the infection rate [5].

Primary vs. secondary wound healing

In the course of primary wound healing, the wound closes by direct abutment, fusion and scarring of the smooth wound edges [2]. They fuse with minimal new tissue formation. Healing is not delayed by inflammation or wound secretion. Secondary wound healing refers to delayed and gradual wound closure due to a wound healing disorder. After formation of granulation tissue in the wound bed and epithelialization from the wound margin, the wound tends to scar severely (contraction). In a primary healing wound, it takes 48 hours for the wound to close without drainage, so there is no further risk of contamination. Therapeutic measures of secondary healing, acute and chronic wounds are challenging because all phases of wound healing are affected.

Dressing change: “non-touch” technique

The surgical wound at the end of the surgical procedure must be covered with a sterile dressing. The first dressing change of a primarily closed wound is advisable after approximately 48 hours at the earliest, unless an earlier dressing change is necessary due to possible complications (secretion, pain, bleeding in dressing) [2,5]. Once the wound is dry and closed, it is not necessary to apply another sterile wound dressing for hygienic reasons [5]. Shorter time intervals increase the risk of fibrin network injury [2]. Wound covers that have bled through or become moist should be changed immediately. The “non-touch” technique is recommended for dressing changes, i.e. disposable gloves are used to remove the dressing and sterile gloves or instruments are used to dress the wound and apply the first layer of dressing [2]. The goal is to avoid touching skin, wound or sterile items with bare hands or non-sterile instruments.

Swiss healthcare system: NOSO strategy

Reducing healthcare-associated infections is a high priority for the Federal Council. For this reason, the NOSO strategy was declared a priority measure in the overall health policy review “Health 2020” [1]. NOSO builds on what is proven, fills in gaps, and takes into account the varying conditions of health care facilities. A strategic goal and a set of key measures are defined for each of five areas. The project was developed in close collaboration with the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Health Directors, H+ The Hospitals of Switzerland, Curaviva Association of Homes and Institutions Switzerland, the Swissnoso expert group, as well as medical societies and other important stakeholders. It is coordinated with federal measures such as the antibiotic resistance strategy (StAR) and the pilot programs within the framework of the quality strategy, so that a joint approach without duplication is ensured.

Literature:

- Federal Office of Public Health: NOSO Strategy, www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-noso–spital–und-pflegeheiminfektionen/ueber-die-strategie.html, (last accessed Sept. 29, 2021).

- Dressing Changes for Aseptic and Septic Wounds, The Practice Guide Issue 01.2019, www.die-praxisanleitung.de, (last accessed Sept 29, 2021).

- Mangram AJ, et al: Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Am J Infect Control 1999; 27(2): 97-134.

- National Reference Center for Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections 2015, www.nrz-hygiene.de/fileadmin/nrz/ module/op/reference_data_2010-2014 (last accessed Sept. 29, 2021).

- Robert Koch Institute (RKI), www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/Krankenhaushygiene (last accessed 29.09.2021).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(10): 34