Both habitual rhonchopathy, or simple snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) are sleep-related breathing disorders. While snoring is not associated with any consequences for the affected person, because it does not affect the quality of sleep, in OSAS health risks lurk for the patient and his environment.

Habitual rhonchopathy is more of a social problem, as the bed partner is often much more likely to be affected than the nocturnal disturber themselves due to the loudness. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, on the other hand, can have serious consequences, not only for the sufferer, but also – in terms of potential accidents – for those around them. The distinction between rhonchopathy and OSAS is sometimes not so easy. Basically, rhonchopathy can be a symptom of OSAS, but it does not have to be.

When patients suffer from sleep fragmentation due to apneas/hypopneas (box) and thus non-restorative sleep with increased daytime sleepiness, this is referred to as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, explained Dr. Nikos Kastrinidis, senior physician at the Department of Ear, Nose, Throat, and Facial Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich [1]. This is measured by the Apopnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI), which is divided into three degrees: “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe.”

- Light = 5-15/hour

- Medium = 15-30/hour

- Heavy = >30/hour

However, there may be people who have an elevated AHI of, for example. 15 but are completely symptom-free – these then also do not need to be treated, the expert explained: “We only speak of patients with OSA if the increased AHI is also accompanied by non-restorative sleep or daytime sleepiness.”

Manifestation and diagnostics

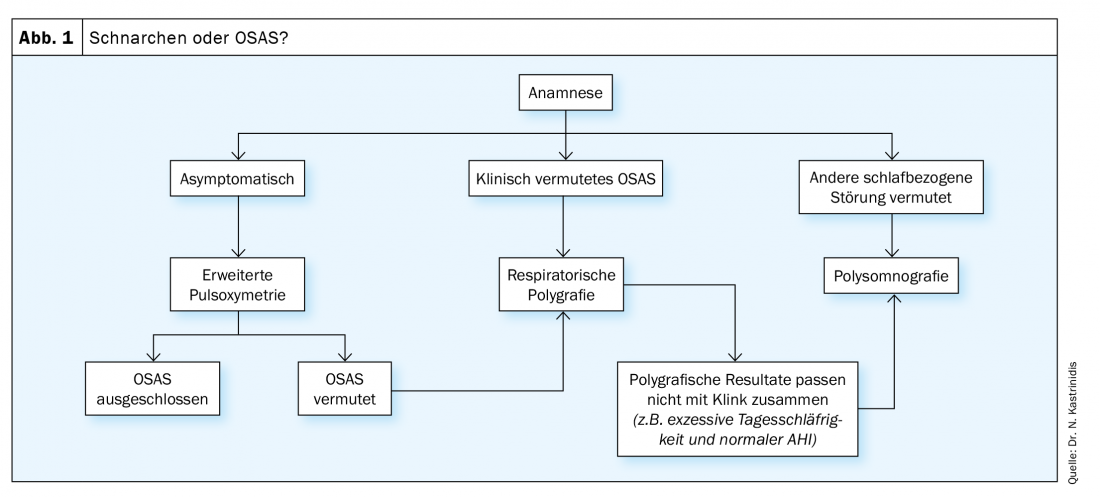

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome manifests itself in many ways. Characteristics include excessive daytime sleepiness (TV sleep, car sleep), fatigue, tiredness after getting up (hypersomnia), often associated with headaches, loud, irregular snoring and breathing pauses during the night. All of this ultimately leads to non-restorative sleep. Resulting complications and associations with OSAS primarily include the risk of falling asleep at the wheel of a car (accident rate increased 1.3 to 12 times) and increased cardiovascular risk (arterial hypertension), but chronic headaches and loss of libido may also occur. For the exact procedure in practice, Dr. Kastrinidis presented an algorithm that offers help in differentiating from snoring (Fig.1). In doing so, he advises performing polysomnography in unclear cases where the practitioner is not quite sure if he or she is dealing with OSAS and is considering another sleep-related disorder.

Measurement techniques

Advanced pulse oximetry is a screening device that should be worn for at least 6 hours, and the device cannot distinguish whether the patient is asleep or awake during the wearing period. Pulse rate, oxygen saturation and respiratory rate are measured. It should only be used in cases of low pretest probability for reassurance or exclusion. If the findings are unclear, further clarification is indicated.

Respiratory polygraphy is somewhat more complex, but also relatively easy and straightforward to perform on an outpatient basis. In addition to extended pulse oximetry, thoracic and abdominal excursion and body position can also be measured here, among other things.

Polysomnography is the most accurate examination. Again, heart rate, percutaneous O2 saturation, flow (nasal and/or oral), chest and abdominal excursion, body position, and snoring are measured. In addition, however, the EEG, ECG, EMG (M. tibialis ant, submental) and EOG (eye movements) are measured and the whole is recorded on video. This can no longer be done at home, but is done in a sleep lab.

Conservative therapies

Several non-surgical and surgical methods are available to treat OSAS, although surgery is rarely the first option and should only be used when conservative options have been exhausted.

CPAP

In order to achieve any effect at all, the mask must be worn for at least 4 hours per night on more than 80% of all nights, Dr. Kastrinidis pointed out at the outset. “That’s very long and very much, and young people in particular have quite a hard time with that.” Nevertheless, CPAP is still considered the gold standard, but there is a 35.6% failure rate – “they then have to be taken care of with other methods.”

Mandibular advancement device (MRD) (Progenating splint)

In the case of normal snoring, sufferers must pay for the progenitive splint themselves; in the case of OSAS, at least part of it is covered by the insurance company. Since this year already without CPAP intolerance – until 2020 this still had to be in the diagnosis to get a subsidy for the splint or brace. The brace prevents the base of the tongue from falling back and also addresses the soft palate if necessary. The acceptance depends on the construction height and design of the rail. “In principle, it’s a good thing, but it’s relatively clunky and uncomfortable to wear,” is the medical professional’s assessment.

MRD is contraindicated in patients with epilepsy, those with poor dental health, and patients with craniomandybular dysfunction (CMD, which can occur or be exacerbated during therapy). Known short-term side effects include discomfort in the masticatory muscles, excessive salivation, and altered bite sensation; long-term side effects may include undesirable tooth movement, occlusal changes, or CMD. Predictors of treatment success include low AHI, young age, low BMI, back position-associated OSAS, female gender, and low neck circumference.

Sleep position therapy

POSAS (positional OSAS) occurs only in mild and moderate OSAS. There are various devices for treatment, including an app that can be downloaded to a cell phone, but Dr. Kastrinidis doesn’t think much of it: “You’d have to strap the cell phone to your chest all night. Backpacks that you put on and that force you into the optimal position while you sleep work better. As a kind of “home remedy”, the physician suggests that one could also sew a tennis ball into one’s pajamas, which would also prevent a supine position. There are also harnesses that beep whenever the wearer gets supine.

Nasal breathing

In terms of nasal breathing, both nasal surgery and devices such as nasal staples may be options. For Dr. Kastrinidis, this is a controversial topic: “I would never operate on someone’s nose for snoring who has no nasal symptoms. If I have nasal breathing problems plus OSAS – ok. But not the other way around.” What is known, however, is that the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) can improve significantly with the surgical method, he said. And surgery may also be warranted for CPAP intolerance: “If the mask isn’t working because the nasal septum needs to be straightened, surgery makes sense.”

Didgeridoo

As early as 15 years ago, a study showed that playing a didgeridoo, the instrument of the Australian aborigines, for at least 30 minutes a day for at least 5 days a week had a positive effect [2]. The special demands of playing the instrument lead to a strengthening of the entire pharyngeal musculature. However, the so-called asate therapy usually uses modern instruments made of plexiglass, which keeps the noise level tolerable for the environment compared to the traditional bamboo material. The success rate with the didgeridoo is surprisingly high, while no side effects are known.

Weight reduction

Dr. Kastrinidis specifically emphasized the importance that weight loss can have on OSAS: 10-15% less of baseline weight on the scale can result in a 50% reduction in AHI.

Operational options

Several options are also available for surgical therapy, including tonsillectomy, hypoglossal stimulator, tongue base reduction, epiglottopexy, or bimax. For a BMI >35 kg/m2, the expert advises bringing in a bariatric team.

Congress: 60th Medical Congress Davos – Online event

Literature:

- Workshop “Simple Snoring or Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome”; 60th Davos Medical Congress – Online Event, February 11, 2021.

- Puhan MA, et al: Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005; 332: 266-270; doi: 10.1136/bmj.38705.470590.55.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(4): 18-19.