After aortic valve stenosis, mitral valve regurgitation is the second most common valvular defect. It can usually be corrected by reconstruction of the native valve.

After aortic valve stenosis, mitral regurgitation is the second most common valvular heart defect in Europe [1]. Minimally invasive mitral valve reconstruction is a surgical and primarily tissue-preserving treatment of the mitral valve apparatus. Surgical access is possible via lower median hemi-sternotomy as well as mininally invasive endoscopic access via right lateral minithoracotomy. If reconstruction is not possible for anatomic reasons, conversion to biological or mechanical mitral valve replacement is indicated.

Epidemiology

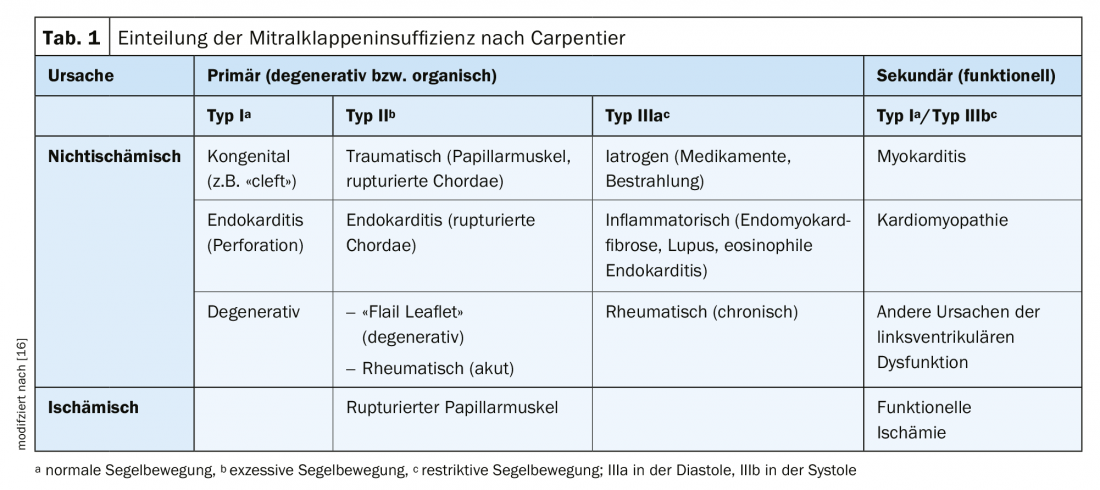

Mitral valve regurgitation is divided into types according to Carpentier (Table 1). Primary mitral regurgitation is a disease of the mitral valve and the mitral valve leaflet. The most common causes include degenerative changes such as tendon filament rupture, prolapse, and valve annulus calcification (60-70%) followed by endocarditis (2-5%) and rheumatic fever (2-5%).

Secondary mitral regurgitation results from changes in the geometry of the mitral valve apparatus. Reasons include ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy, ischemic left ventricular dysfunction, or myocarditis. In contrast to primary mitral regurgitation, in secondary mitral regurgitation the valve is not pathologically altered a priori.

In chronic mitral regurgitation, symptoms such as palpitations (due to atrial fibrillation) and symptoms of left heart failure as well as right heart failure may usually occur late. In contrast, acute insufficiency can lead to fulminant courses with pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock.

Diagnostics

Patients with mitral regurgitation present clinically primarily with a holosystolic heart murmur with punctum maximum in the 4. respectively 5. ICR in the medioclavicular line and classic heart failure symptoms such as edema, dyspnea on exertion, dizziness, and fatigue. In addition, the ECG provides information on cardiac rhythm, such as new-onset atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or a positive Sokolow-Lyon index as a sign of left ventricular hypertrophy. If mitral regurgitation is suspected, transthoracic echocardiography is the diagnostic gold standard for describing valve function, underlying pathology, and severity. In addition to the assessment of left ventricular function (LVEF) and determination of the diameters of atria and ventricles, the assessment of the function of the right ventricle is of highest relevance to assess the consequences of mitral regurgitation. If orienting transthoracic echocardiography reveals mitral valve vitium, supplemental evaluation by transesophageal echocardiography is recommended because it allows even more accurate assessment of valve pathology.

Mitral valve surgery remains the gold standard in the treatment of primary mitral regurgitation. In symptomatic patients with primary chronic mitral regurgitation and an LVEF >30% (class I B recommendation) and in asymptomatic patients with an LVEF <60% and/or a left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) >45 mm, surgical repair of the mitral valve is recommended (class I B recommendation). Reconstruction of the mitral valve should be attempted whenever possible [2].

According to European guidelines, even in asymptomatic patients with preserved left ventricular function (LVESD <45 mm and an LVEF >60%) and new-onset atrial fibrillation or pulmonary hypertension, mitral valve repair is strongly recommended (class IIa B recommendation). This also applies to asymptomatic patients with a “flail leaflet” in the presence of a torn tendon suture or severe left atrial dilatation (volume index >60 mL/m2 body surface area) (Class IIa C recommendation) [2].

Asymptomatic patients with severe primary mitral regurgitation who have no indication for surgery should be monitored cardiologically at annual intervals. Echocardiography, as well as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) neurohormonal activity, are crucial for the assessment of progression [3,4].

Secondary mitral regurgitation is a geometric disorder of the left ventricle. It is most common in dilated and ischemic cardiomyopathy. In this case, the interaction of a change in the position of the papillary muscles, tensile stress on the leaflets (tethering), and consecutive malcoaptation results in mitral valve insufficiency [5].

Indication conference

All patients with severe mitral regurgitation are discussed at the University Hospital Basel (USB) in a “Heart-Team” indication conference with the presence of at least interventional, non-interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. If the indication for surgical rehabilitation is given, a detailed educational discussion takes place with the patient. The conventional approach via a sternotomy versus the procedure via a right lateral minithoracotomy is also discussed there. Primarily, all isolated mitral valve reconstructions are performed at the USB via minimally invasive minithoracotomy; there are few contraindications, such as marked atherosclerosis [6], severe thoracic deformities, and moderate or severe aortic regurgitation. If mitral valve reconstruction is part of a combination procedure (e.g., aortic valve replacement, coronary bypass surgery, etc.), sternotomy is the access route of choice.

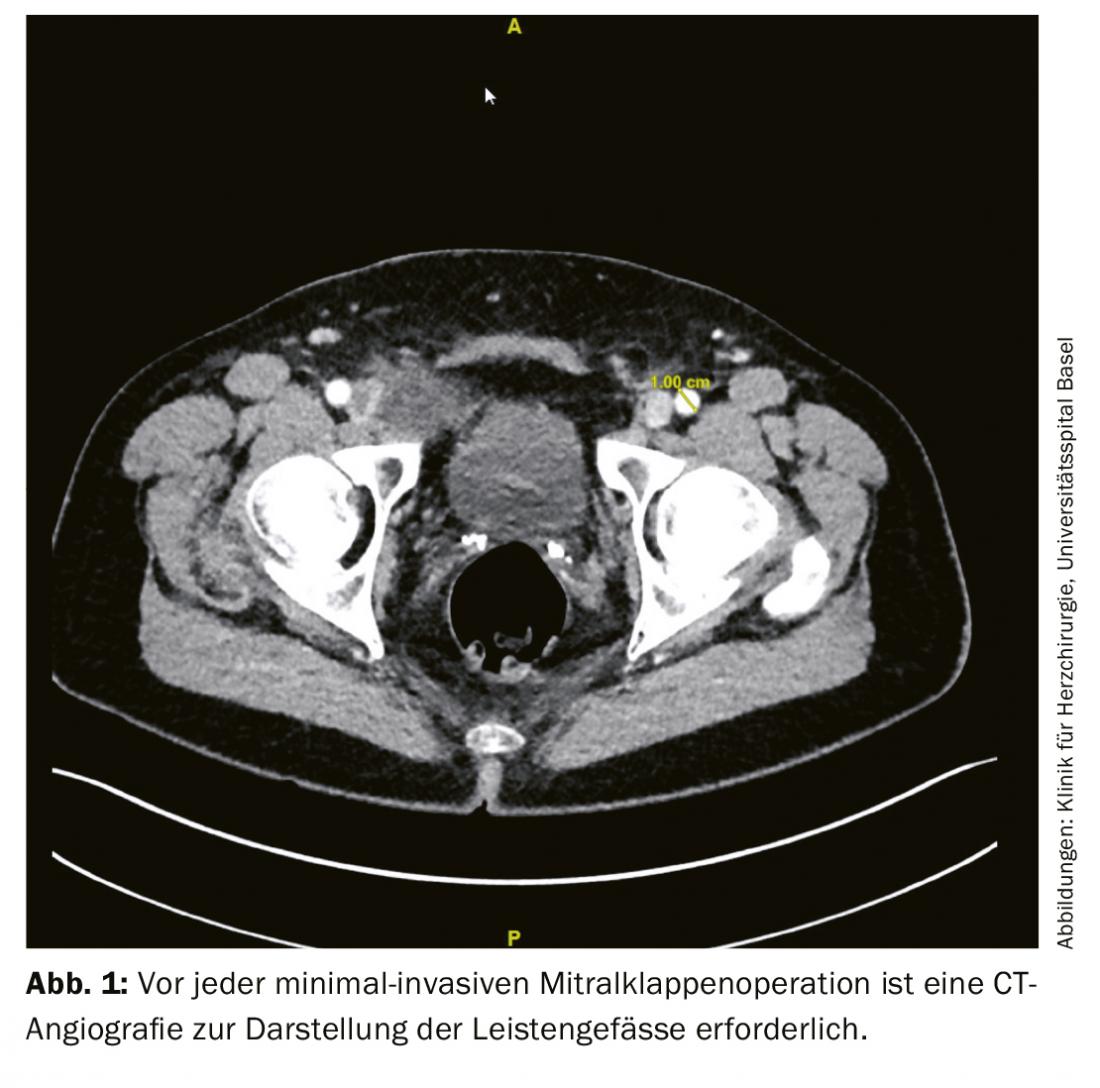

After the patient’s consent, preoperative examinations are performed. This includes transesophageal echocardiography and a CBC, computed tomography of the coronaries or coronary angiography to rule out coronary artery disease. Furthermore, duplex ultrasonography of the neck vessels is recommended for all patients older than 65 years to exclude higher-grade stenoses [7]. For planning a minimally invasive operation on the heart, a computed tomographic examination of the entire aorta up to and including the inguinal vessels is also recommended. This examination describes in particular relevant changes or thrombotic deposits of the aorta as well as inguinal vessels and possible pulmonary adhesions (Fig. 1).

Operative procedure for minimally invasive mitral valve reconstruction

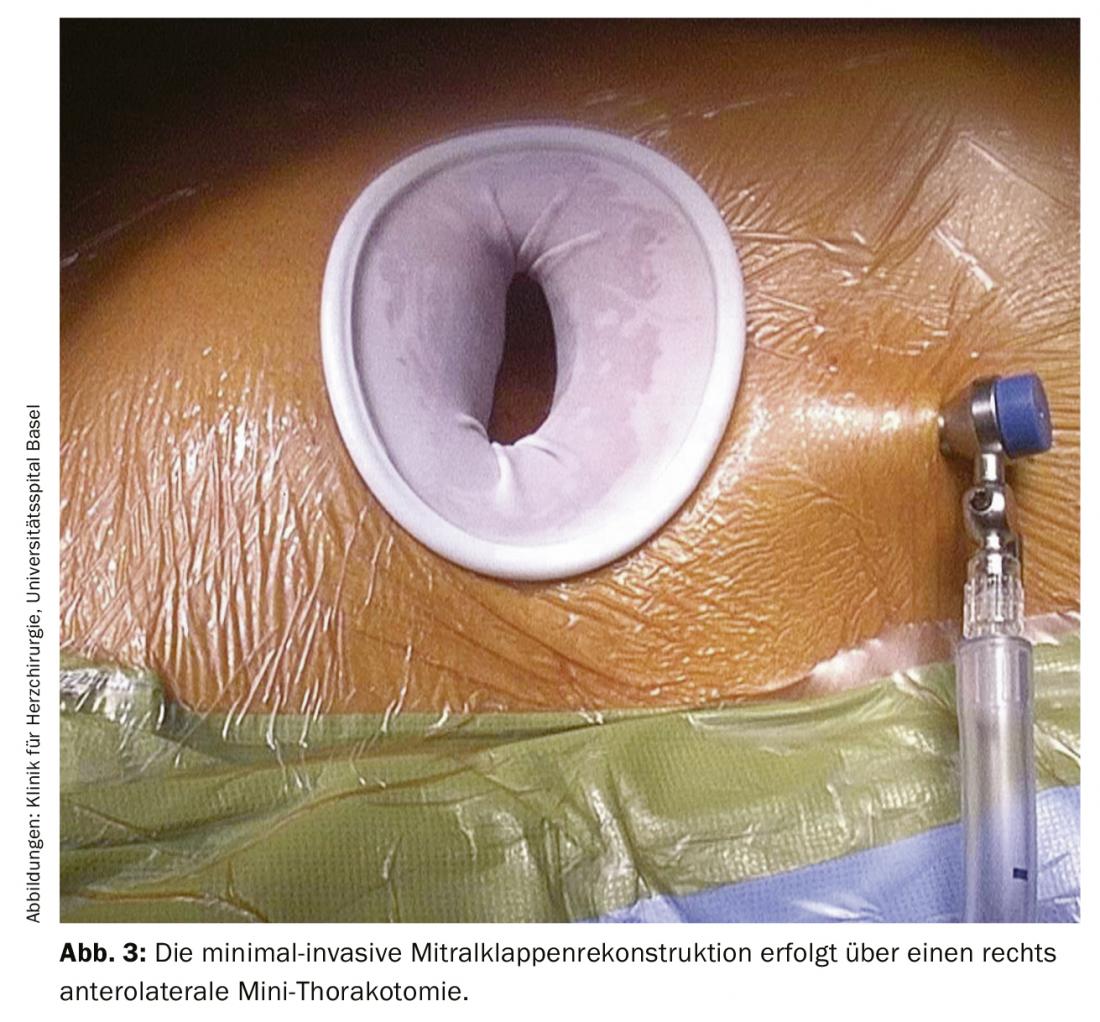

In cardiac surgery at the USB, isolated minimally invasive mitral valve surgery initially involves a small skin incision of approximately 4-5 cm on the right side of the chest. The skin incision can be made at the lower edge of the nipple at the transition from non-pigmented to pigmented skin (Fig. 2). This approach has mainly cosmetic advantages of a later almost invisible scar without restriction of sensitivity. In addition, a rigid rib spreader (Fig. 3) is not normally required in this case; this provides maximum protection for the intercostal nerves. After single-lung ventilation (double lumen tube) exclusively of the left lung, the pericardium is opened. The endoscope is inserted through a small incision in the skin, which is later used for drainage. This allows the interior of the chest and heart to be illuminated, displayed and transmitted to two large high-resolution 3D monitors in the operating room. The access route via right minithoracotomy with improved visibility allows better and more accurate assessment and surgery of the mitral valve. After connecting the patient to the heart-lung machine via a small incision and cannulation of the inguinal vessels (Fig. 4), the pericardium is opened, the aorta is clamped, and the heart is cardioplegated. After cardiac arrest is achieved, mitral valve pathology is assessed first, followed by reconstruction.

Reconstruction versus mitral valve replacement

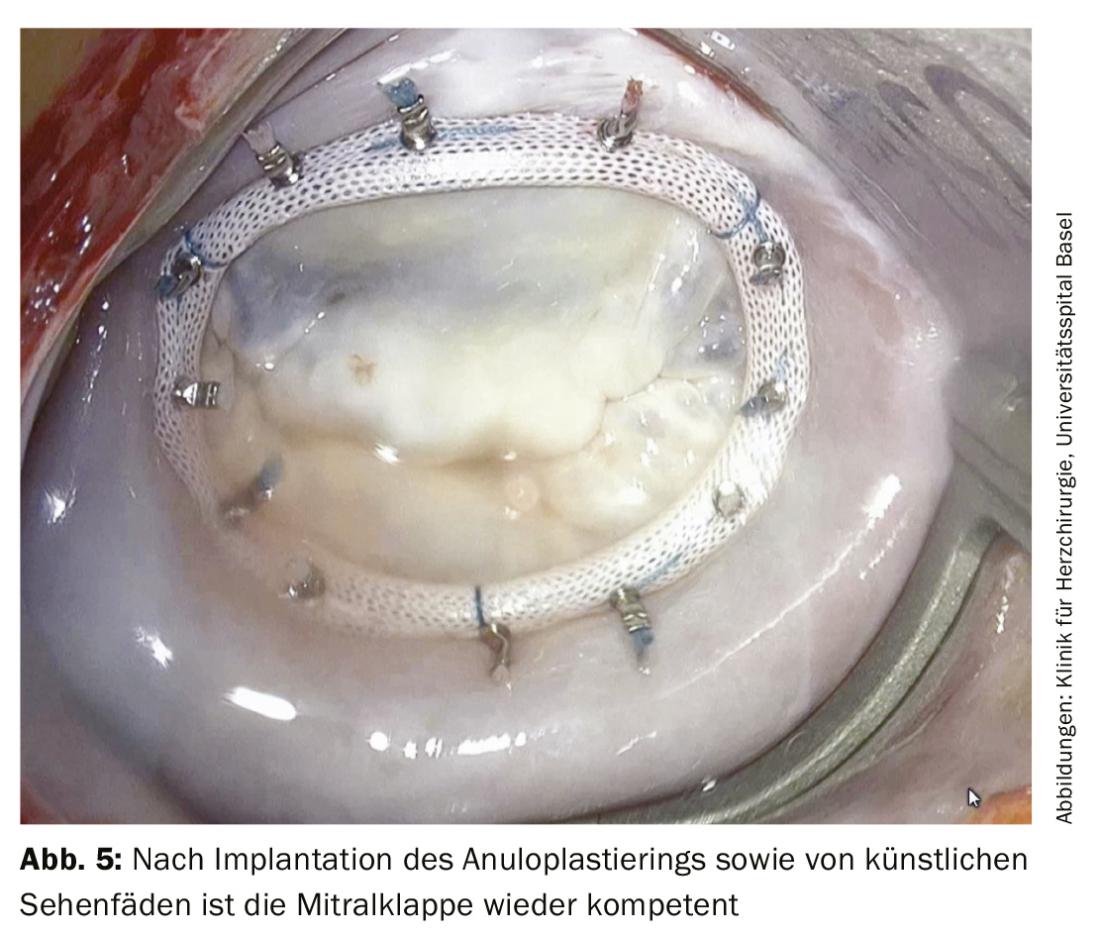

In primary mitral regurgitation, mitral valve repair is the gold standard. The principles already established by Carpentier in 1971 of maintaining sail mobility, restoring annulus geometry, and allowing the largest possible coaptation area between the two sails still apply [8]. According to the guiding principle “Respect rather than resect”, modern mitral valve surgery reconstructs as tissue-sparingly as possible, i.e. usually without leaflet resection [9].

Ring annuloplasty is almost always performed as part of mitral valve repair for support. This is done by means of a so-called mitral annuloplasty ring, which is sewn in on the atrial side (Fig. 5). If there is also a rupture of the tendon suture, the corresponding part of the leaflet is reattached to the papillary muscle using artificial Gore-Tex® tendon sutures (Fig. 6).

After the performed reconstruction, the mitral valve is evaluated perioperatively by echocardiography. At the end of the operation after departure from the heart-lung machine, the thoracotomy is closed, the inguinal vessels are reconstructed, and then the wounds are closed with an absorbable intracutaneous suture. The advantage of this is that almost invisible scars are created without limiting sensitivity and no further stitches need to be removed in the course.

Basically, morbidity and mortality are comparable for both access routes, minimally invasive and sternotomy [10]. It was found that although there was a longer ischemia time (minimally invasive 101.3 ± 32.4 min vs. sternotomy 82.3 ± 38.5 min; p<0.001) and bypass time (minimally invasive 136.8 ± 42.0 min vs. sternotomy 108.1 ± 48.3 min; p<0.001) occurs with minimally invasive mitral valve repair, but patients require blood transfusions less frequently (minimally invasive 14% vs. sternotomy 22.9%; p=0.03), and there are fewer rehospitalizations within the first 30 days (minimally invasive 4.4% vs. sternotomy 12.6%; p=0.01) [11]. Good wound healing and excellent cosmetic appearance of the scar after minimally invasive mitral valve reconstruction are shown [12].

Due to the underlying pathology, the risk of re-insufficiency in secondary mitral regurgitation is higher than after primary regurgitation [13,14] despite successful mitral valve repair. Survival in the prospective randomized trial was 14.3% for patients with mitral valve reconstruction versus 17.6% for mitral valve replacement (p=0.45) [13]. In a meta-analysis, the eight-year survival rate after reconstruction was 81.6 ± 2.8% and after replacement 79.6% ± 4.8% (p=0.42) [14]. If biological or mechanical replacement of the mitral valve is required, this can also be performed via a minimally invasive approach.

Postoperative course

After surgery, each patient is initially cared for in the intensive care unit for one to two days and then in the cardiac surgery normal care unit for three to five days, where physiotherapy and respiratory therapy are started immediately and then continued in a three-week rehabilitation program. In addition, angiologic duplex sonography of the cannulated inguinal vessels is performed prior to discharge to rule out aneurysm spurium or stenosis after inguinal cannulation. At the end of the hospital stay, transthoracic control echocardiography is performed for final evaluation of the reconstruction. Furthermore, 3 and 12 months postoperatively, as well as yearly thereafter, echocardiographic and clinical check-ups with established cardiologists will be performed. In case of mitral valve reconstruction (annuloplasty) or biological mitral valve replacement, oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists is given for at least three months postoperatively. Patients with mechanical mitral valve replacement require lifelong oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists [2]. If the mitral valve cannot be reconstructed, implantation of a mechanical mitral valve prosthesis is generally recommended for patients younger than 65 years of age (class IIa C recommendation) and without contraindication of permanent oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (class I C recommendation). Otherwise, implantation of a biological mitral valve prosthesis is indicated, although the patient’s wishes are of course the primary consideration in the choice of prosthesis. After biological mitral valve replacement, oral anticoagulation is required for only three months [15].

In cardiac surgery at USB, more than 95% of isolated mitral valve reconstructions are performed via a minimally invasive approach. The surgical risk is lower with minimally invasive surgery than with the conservative approach, and the reconstruction rate is significantly higher at 98% (2018: 96%).

Conclusio

Reconstruction offers excellent results in primary mitral valve regurgitation due to degeneration and should always be favored as the gold standard. Prior to any mitral valve procedure, pathology on the leaflets and left ventricle is evaluated and an individualized reconstruction strategy is created.

Reconstruction can also achieve good long-term results in secondary mitral regurgitation. Compared with sternotomy, mitral valve surgery using mininally invasive anterolateral minithoracotomy offers better surgical results [10] with additional advantages, especially an excellent cosmetic outcome, and is therefore very well accepted by patients.

Take-Home Messages

- Transthoracic echocardiography is the gold standard in the diagnosis of mitral regurgitation.

- Surgical repair remains the gold standard in the treatment of severe mitral regurgitation.

- Isolated surgery on the mitral valve can almost always be performed minimally invasively.

- Mitral regurgitation can usually be corrected by reconstruction of the native valve.

- After mitral valve repair, oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist for 3 months is indicated.

Literature:

- Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al: Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 368(9540): 1005-1011, Sep 2006, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8.

- Baumgartner H, et al: 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 38(36): 2739-2791, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391.

- Rosenhek R, et al: Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation, 113(18), 2238-2244, May 2006, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.599175.

- Pizarro R, et al: Prospective Validation of the Prognostic Usefulness of Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Asymptomatic Patients With Chronic Severe Mitral Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 54(12): 1099-1106, Sep. 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.013.

- Sündermann SH, Falk V: Surgical treatment of secondary mitral regurgitation: “best-practice” recommendation for optimal long-term results. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, 31(4): 269-275, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1007/s00398-017-0147-0.

- Youssef SJ, Millan JA, Youssef GM, et al: The role of computed tomography angiography in patients undergoing evaluation for minimally invasive cardiac surgery: An early program experience. Innovations: Technology and Techniques in Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, 2015, 10(1): 33-38, doi: 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000126.

- Naylor AR, et al: Editor’s Choice – Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 55(1): 3-81, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.06.021.

- Carpentier A, et al: A new reconstructive operation for correction of mitral and tricuspid insufficiency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 61(1): 1-13, Jan. 1971.

- Perier P, et al: Toward a New Paradigm for the Reconstruction of Posterior Leaflet Prolapse: Midterm Results of the ‘Respect Rather Than Resect’ Approach. Ann Thorac Surg 86(3): 718-725, Sep. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.05.015.

- Percy E, et al: Long-Term Outcomes of Right Minithoracotomy Versus Hemisternotomy for Mitral Valve Repair. Innov Technol Tech Cardiothorac Vasc Surg, p. 155698451989196, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1177/1556984519891966.

- Goldstone AB, et al: Minimally invasive approach provides at least equivalent results for surgical correction of mitral regurgitation: A propensity-matched comparison. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2013, 145(3): 748-756, doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.093.

- Grossi EA, et al: Impact of minimally invasive valvular heart surgery: A case-control study. Ann Thorac Surg 71(3): 807-810, Mar. 2001, doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02070-1.

- Acker MA, et al: Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med 370(1): 23-32, Jan. 2014, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312808.

- Lorusso R, et al: Mitral valve repair or replacement for ischemic mitral regurgitation? The Italian Study on the Treatment of Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation (ISTIMIR). Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2013, 145(1): 128-139, doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.042.

- Sousa-Uva M, et al: 2017 EACTS Guidelines on perioperative medication in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg 53(1): 5-33, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx314.

- Nickenig, et al: Consensus of the German Society of Cardiology – Cardiovascular Research – and the German Society for Thoracic, Cardiovascular and Vascular Surgery on the treatment of mitral valve regurgitation. Cardiology 2013, 7: 76-90.

CARDIOVASC 2020; 19(1): 12-16