The treatment of colorectal carcinoma has improved greatly. Patients today benefit from multimodal therapeutic approaches even in advanced stages and metastases. Management must be interdisciplinary.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Europe. Resection of the tumor is essential if the intention is curative. Over the past 20 years, the treatment of colorectal cancer has improved significantly. Patients today benefit from the strategic use of multimodal therapy even in advanced stages and metastases [1].

Interdisciplinarity and tumor board in CRC

The disciplines of oncology, surgery, gastroenterology, radiation oncology and medical genetics are closely linked in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal carcinoma. All patients with colon or rectal cancer should present to an interdisciplinary tumor board at diagnosis, especially patients with metastases and recurrences. It has been shown that tumor board presentation significantly increases the number of patients offered metastatic ablation and surgery [2].

Staging of the CRC

The mandatory investigations for treatment decision in colon and rectal cancer are digital rectal examination and complete colonoscopy with biopsy. In the case of non-passable stenosis, completion colonoscopy should be performed three to six months postoperatively; alternatively, virtual colonoscopy or barium enema may be performed if available. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as a tumor marker and computed tomography of the thorax are part of the complete staging. According to the S3 guidelines, ultrasonography of the liver is sufficient to exclude liver metastases [3], whereas contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is recommended in the European ESMO guidelines [1]. In rectal cancer, more precise local staging and rigid rectoscopy to determine the height of the tumor’s lower margin should also be performed to determine whether neoadjuvant therapy is necessary. The relation to the sphincter and the determination of the T- and N-stage can be determined with rectal endosonography (ERUS) as well as pelvic MRI – the therapeutically and prognostically important indication of the distance of the tumor to the mesorectal fascia, however, only with pelvic MRI. If rectal cancer extends to 1 mm or less to the mesorectal fascia, the local recurrence risk is significantly increased [4].

PET-CT currently plays no role in the routine diagnosis of CRC. The value of PET-CT in metastatic disease (Stage IV) is controversial. It was shown in a randomized trial that PET-CT reduced the number of unnecessary resection attempts [5], but other studies have shown no difference in patient-relevant events with or without PET-CT [6]. It is considered certain that PET-CT within four weeks after administration of chemotherapy or antibody therapy has no diagnostic value [7]. Lymph node staging by imaging remains unreliable in both colon and rectal cancer and, in the case of rectal cancer, the combination of ERUS, CT, and MRI has not changed this much, as recent meta-analyses have shown. Lymph node staging must ultimately be left to pathology. The proximity of rectal cancer to the mesorectal fascia, the so-called “circumferential resection margin” (CRM), and the presence of “extramural vascular invasion” (EMVI) are more important than lymph node status with regard to the decision for neoadjuvant therapy, but also the prognosis in rectal cancer.

Intraoperative staging consists of exploration of the abdominal cavity and resection of the tumor with consideration of adequate spacing of the resection margins. Sentinel lymph node excision (“sentinel node biopsy”) has no role in the treatment of colorectal carcinoma. Radical resection of the supplying vascular pedicle with the associated lymphatic drainage area is important.

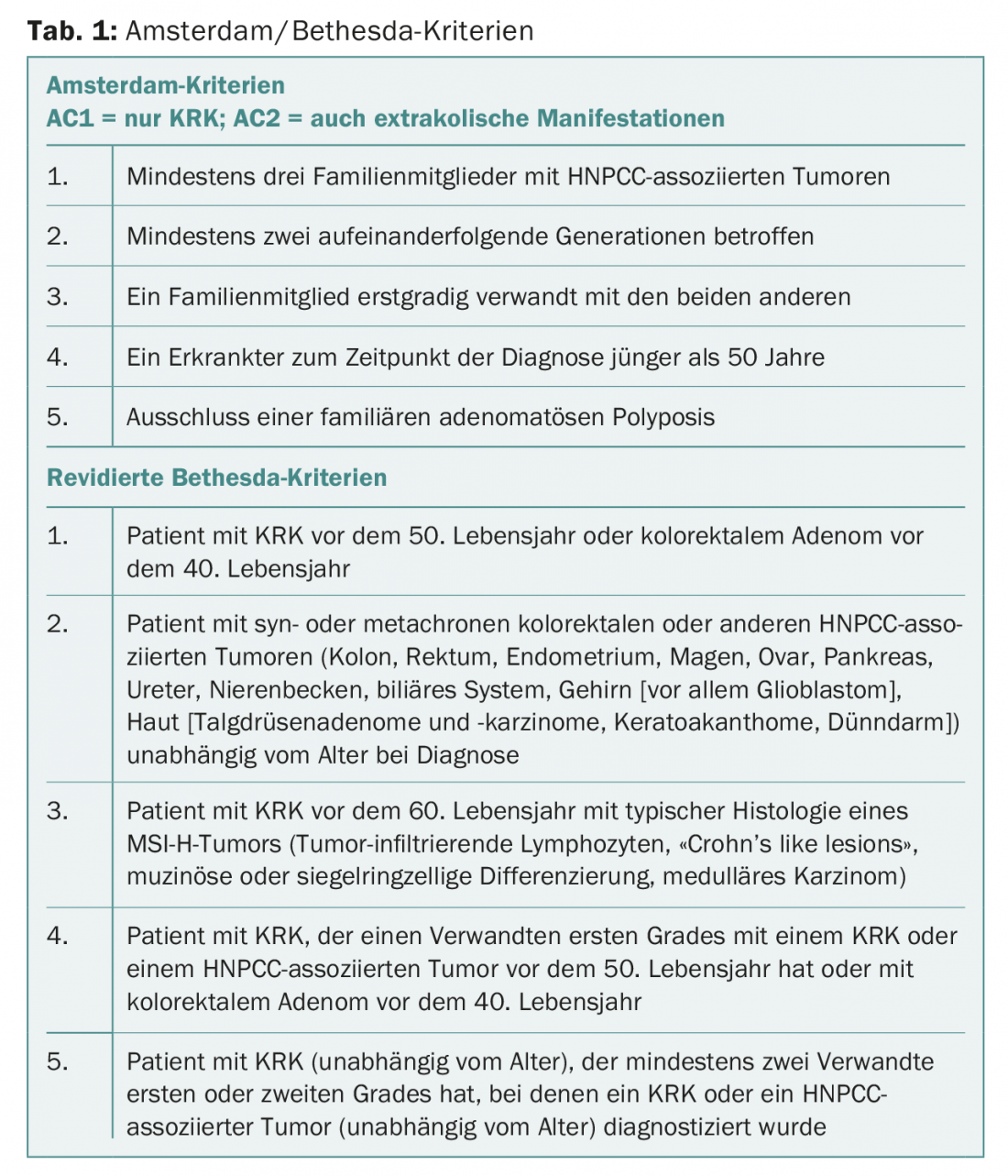

According to the S3 guidelines, microsatellite examination is optional in non-metastatic carcinoma and recommended in suspected HNPCC or poorly differentiated colon carcinoma. Since the Amsterdam or Bethesda criteria (Tab. 1) are not sensitive enough due to current family size, the European ESMO guidelines recommend routine screening for possible microsatellite instability in all patients under 70 years of age to exclude familial colon cancer in the setting of hereditary colon cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome). years and in patients over 70 Years with positive Bethesda criteria. Many certified colorectal cancer centers now adhere to the more stringent ESMO guidelines. In metastatic CRC, RAS and B-RAF mutation status and microsatellite instability should be tested due to prognostic and therapeutic relevance. Other biomarkers such as circulating tumor cells, liquid biopsy, and whole-genome/exome/transcriptome analysis are discussed but have yet to have any practical consequence in everyday life [1].

Recent data indicate that right-sided and left-sided colon tumors are pathogenetically different tumors (keyword “sidedness”). Left-sided colon tumors likely respond better to anti-EGFR therapy (cetuximab) than right-sided colon tumors, and left-sided colon tumors have different pathogenetic markers compared with rectal cancers [8].

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy in Stage 1-3 CRC.

Neoadjuvant therapy is not indicated for resectable colon carcinoma without metastasis. The indication for neoadjuvant therapy of rectal cancer is based on the location (proximal, mid, or distal rectum) depending on the T and N stage. Regardless of height localization, a CRM ≤1 mm or an EMVI + is always an indication for neoadjuvant therapy.

Irradiation consists of either short-term irradiation with 5× 5 Gy followed by immediate surgery (short-term regimen) or conventional fractionated radiochemotherapy (1.8-2.0 Gy to 45-50.4 Gy) with an interval of six to ten weeks until surgery (long-term regimen).

Adjuvant therapy is indicated in colon cancer with lymph node involvement (stage 3) or in selected high-risk situations at stage 2 (T4, tumor perforation, emergency surgery, number of lymph nodes examined <12) and consists mostly, in patients younger than 70 years, of oxaliplatin-containing protocols. Because successful adjuvant chemotherapy was usually initiated within six weeks in the randomized trials, adjuvant therapy after surgery should be initiated within six weeks or less if possible. be made as soon as possible. The indication for postoperative (radio)chemotherapy in rectal cancer is based on T, N, CRM, and Mercury (completeness of mesorectal excision in pathologic staging) [4].

Radical resection of the colon

Surgical therapy of colon carcinoma consists of radical resection including lymphatic drainage. The minimum number of lymph nodes in the specimen is 12. Organs adherent to the tumor must be resected with multivisceral en bloc resection. For tumors of the cecum and ascending colon, a right hemicolectomy is performed. This implies a central truncation of the ileocolic artery and thus also a resection of 5-10 cm distal ileum, truncation of the right-sided branches of the medial colic artery, the right-sided omentum majus and, if a dextra colic artery is present (only 15% of all patients), a central truncation of the same. In the extended right hemicolectomy, the median colic artery is also ligated centrally, and the lymph nodes of the dextra gastroepiploic artery, the large gastric curvature, and above the pancreatic head are resected.

For transverse tumors, both colonic flexures are also resected, the colic artery is centrally ablated, the omentum is resected, and a lymphadenectomy of the large gastric curvature is performed.

In tumors of the left colonic flexure, the medial and sinistral colic arteries are set down at their outlets, and the left omentum is resected close to the stomach.

For tumors of the descending colon, a central transection of the inferior mesenteric artery and an interposition of the left colon in the upper third of the rectum are performed.

For sigmoid carcinomas, central ablation of the inferior mesenteric artery and transection of the colon in the upper third of the rectum with a minimum aboral distance to the tumor of 5 cm are also mandatory. Complete mesocolic excision (CME) with respect of embryonic fascia analogous to total mesorectal excision (TME) in rectal cancer is conceptually plausible in terms of maximal local radicality and high lymph node yield, but prognostically has not been clearly secured so far.

Radical resection of the rectum

Fundamental in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer is total excision of the mesorectum (TME) or partial excision of the mesorectum (PME) for carcinoma of the upper third of the rectum. Since lymph node metastases can occur up to 5 cm distal to the tumor, horizontal transection of the mesorectum is performed at least 5 cm distal to the tumor in proximal rectal carcinoma, and total mesorectal excision is then required consecutively in deeper carcinomas. Organs adherent to the tumor must be resected with multivisceral en bloc resection. The pelvic autonomic nerves should be spared by maintaining the correct resection plane. With regard to aboral resection margins, a safety margin in the area of the bowel wall of 1-2 cm in situ can be accepted for “low-grade” tumors (G1-2) of the lower rectal third, whereas a larger safety margin is desirable for “high-grade” tumors. After neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, an aboral free resection margin of 0.5 cm can be accepted, although this should be secured by intraoperative frozen section examination. The decision to perform a sphincter-preserving procedure for deep-seated rectal cancer after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy can be made no earlier than six weeks after completion of radiochemotherapy.

For T1 rectal cancer without risk factors (G1/2, L0, V0), transanal, usually endoscopic, full-wall excision of the rectum can be performed. Full-wall excision is not adequate for T2 tumors and tumors with suspected lymph node metastases.

Rectal extirpation

When tumor-free resection margins cannot be achieved with sphincter-preserving strategies, cylindrical excision of the anorectum, rectal extirpation, remains the gold standard.

Reconstruction after deep anterior resection

Reconstructions after deep rectal resection include end-to-end anastomosis, transverse coloplasty, side-to-end anastomosis, and colon J-pouch. The functional results of all procedures after two years are identical. However, the short-term results of the latter two procedures are superior to end-to-end anastomosis – so that, because of the technically simpler side-to-end anastomosis, this reconstruction procedure is most commonly used.

Stoma creation in CRC

In rectal cancer excision with TME and deep anastomosis, a temporary deviation stoma should be created, especially after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, and an ileostomy is usually preferred. The deviation stoma does not reduce the rate of anastomotic insufficiency, but it does reduce its morbidity and mortality. Initial avoidance of stomas in rectal surgery does not result in a lower rate of stomas overall. Preoperative counseling by stoma therapists and marking of the stoma site while lying, sitting, and standing simplify postoperative care for this patient population.

“Watch and Wait” strategy in rectal cancer.

The so-called “watch and wait” strategy for complete response after neoadjuvant therapy is the first example of curative, nonsurgical therapy for rectal cancer. Habr-Gama’s group from Brazil demonstrated that 27% of 265 patients no longer had endoscopically and radiologically detectable tumor after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for stage 2-3 rectal cancer. These patients were designated “Stage 0” and followed with a follow-up strategy called “Watch and Wait” with a recurrence rate of only 7.4% at a median follow-up of 58 months [9]. The concept, with the goal of organ preservation, has not yet caught on, but it has been much discussed internationally, followed with interest, and is now being studied by other groups [10].

Laparoscopy in CRC

Laparoscopic resection of both colon and rectal cancers is now considered equal to open resection when patients are appropriately selected. Meta-analyses demonstrate lower postoperative morbidity in the first 30 or 90 days compared with open surgery. Regarding the oncological outcome, there are no differences between the methods (CLASICC trial, COLOR trial, etc.) [11]. In transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME), rectal cancers are removed combined from transanal and transabdominal laparoscopically. The transanal approach offers distinct advantages, especially in the narrow male and/or obese pelvis. The operation can be performed as a “one-team operation” or as a “two-teams operation”, i.e. by two surgical teams simultaneously (Fig. 1) . Initial meta-analyses show oncologic equivalence to laparoscopic deep anterior rectal resection [12] and initial consensus papers support cautious implementation [13].

Postoperative management, ERAS and prehabilitation.

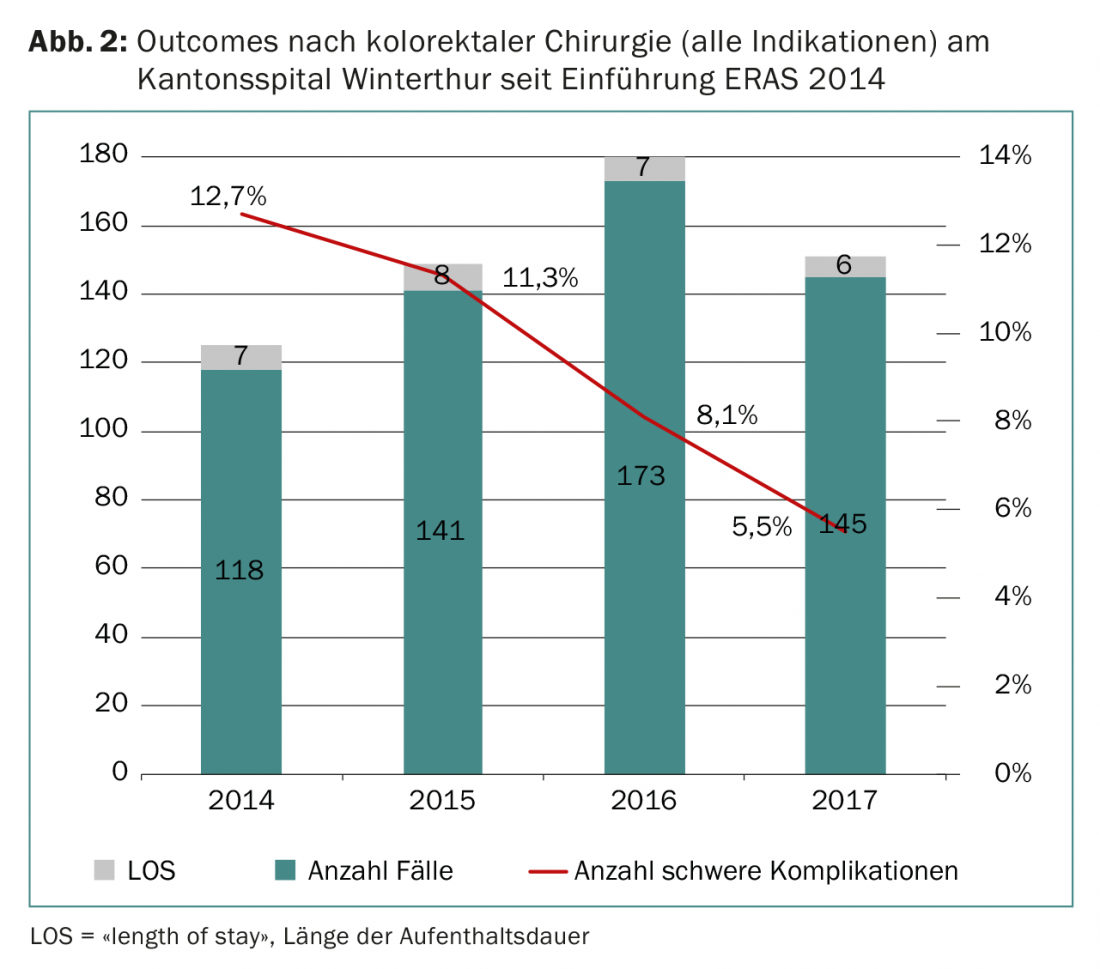

ERAS stands for “enhanced recovery after surgery” and refers to a postoperative care pathway consisting of bundles of practices with efficacy supported by scientific evidence. The ERAS Society was founded in Scandinavia in 2001, and membership of individual centers includes active quality control through a database. ERAS can significantly reduce the postoperative length of stay of patients and also the complication rate after surgery (Fig. 2) [14]. Continuing the ERAS principle, the Winterthur Colorectal Team is conducting a randomized trial on the effect of prehabilitation on postoperative morbidity in patients with colon and rectal resections [15].

The surgery of peritoneal carcinomatosis of CRC.

Until a few years ago, patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis were not considered curable. Meanwhile, cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) can be performed for limited peritoneal carcinomatosis if the “peritoneal cancer index” (PCI) is less than 20, no extraabdominal metastases are present, and removal of all macroscopic tumor manifestations is possible. Often the limiting factor for complete resection is involvement of the small bowel mesentery. Data regarding cytoreductive therapy and HIPEC are becoming increasingly broad. It is now established in many centers with appropriate expertise. Careful patient selection is crucial [16].

Emergency surgery and CRC

Classic emergency surgical indications for underlying CRC include hemorrhage, tumor obstruction, and tumor perforation. Radical resection must always be attempted. Bleeding can be stopped by endoscopic intervention in the majority of cases. Tumor obstruction can be relieved in selected cases by endoscopic stent placement (“bridge to surgery” concept). In obstructing rectal cancer, due to the size of the tumor, a deviation stoma is necessary in most cases to provide the desired neoadjuvant therapy in these advanced tumors.

Liver and lung metastases

Single liver metastases that do not require major liver resection (i.e., more than three segments, so-called major hepatectomy) can be removed simultaneously with colon resection. However, this should be avoided in patients with comorbidities and older age (>70 years). For single metastases smaller than 3 cm, an ablative procedure using radiofrequency or microwave ablation is probably oncologically equivalent to resection.

In patients with multiple metastases or those requiring a so-called major resection, a two-stage resection should be performed.

Most patients with synchronous liver metastases have a positive lymph node status and therefore receive adjuvant chemotherapy anyway. Adjuvant chemotherapy for liver metastases remains controversial. A randomized trial showed that perioperative chemotherapy with six cycles of FOLFOX for mixed nodal status resulted in a reduction in recurrence but did not prolong survival [17].

Patients with initially non-resectable bilobar liver metastasis (metastatic liver) and asymptomatic primary tumor should be offered so-called conversion therapy with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI (“doublet”) and antibodies (bevacizumab or cetuximab or panitumumab) or even “triplet” therapy (FOLFOXIRI) with antibodies. After shrinkage of the tumor mass, secondary resectability can be achieved. In this regard, the superiority of cetuximab over bevacizumab in KRAS wild-type tumors is well established [18]. Similarly, BRAF-mutated tumors with the V600 mutation likely respond better to a combination of FOLFIRI with cetuximab and BRAF inhibitors.

In patients who still do not have enough residual liver tissue for complete resection after successful conversion, there are methods of regenerative liver surgery. These include two-stage liver resection with portal vein embolization or ligation in the interval, as well as newer methods such as ALPPS (“associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy”) or simultaneous double embolization of portal vein and hepatic vein.

More than 50% of liver resections for metastases should currently be feasible laparoscopically in experienced centers.

Pulmonary metastases usually have a small impact on overall survival, but should also be surgically removed if the location is favorable.

Summary

The management of colorectal cancer requires close interdisciplinary collaboration. Multimodal therapy concepts enable a curative therapeutic approach even in advanced and metastatic stages.

Take-Home Messages

- Radical resection by proximal interposition of the vascular axes of the corresponding colonic segments is the basic surgical principle of colonic surgery.

- Tumor distance to the “circumferential resection margin” (CRM) (<1 mm) and “extramural vascular invasion” (EMVI) (“yes”) are the two most important elements in the decision to use neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer.

- Perioperative outcomes of colorectal surgery have been significantly improved over the past two decades with laparoscopic surgery and perioperative care pathways such as ERAS.

- The most technically exciting innovation in colorectal surgery in recent years is the transanal total mesorectal excision.

- Conversion therapy and regenerative liver surgery now allow up to 30% 5-year survival even in extensive liver metastasis.

Literature:

- Van Cutsem E, et al: ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 2016; 27: 1386-1422.

- Segelman J, et al: Differences in multidisciplinary team assessment and treatment between patients with stage IV colon and rectal cancer. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland 2009; 11: 768-774.

- AWMF: S3 guidelines on colorectal carcinoma. Status 2017.

- Glynne-Jones R, et al: Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 2017; 28: iv22-iv40.

- Ruers TJ, et al: Improved selection of patients for hepatic surgery of colorectal liver metastases with (18)F-FDG PET: a randomized study. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2009; 50: 1036-1041.

- Serrano PE, et al: Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) Versus No PET-CT in the Management of Potentially Resectable Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases: Cost Implications of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Oncol Pract 2016; 12: e765-774.

- Glazer ES, et al: Effectiveness of positron emission tomography for predicting chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Archives of surgery 2010; 145: 340-345; discussion 5.

- Arnold D, et al: Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumor side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 2017; 28: 1713-1729.

- Habr-Gama A, et al: Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Annals of surgery 2004; 240: 711-717; discussion 7-8.

- Kong JC, et al: Outcome and Salvage Surgery Following “Watch and Wait” for Rectal Cancer after Neoadjuvant Therapy: A Systematic Review. Diseases of the colon and rectum 2017; 60: 335-345.

- Guillou PJ, et al: Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365: 1718-1726.

- Ma B, et al: Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of oncological and perioperative outcomes compared with laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. BMC cancer 2016; 16: 380.

- Adamina M, et al: St.Gallen consensus on safe implementation of transanal total mesorectal excision. Surgical endoscopy 2018; 32: 1091-1103.

- Greco M, et al: Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World journal of surgery 2014; 38: 1531-1541.

- Merki-Kunzli C, et al: Assessing the Value of Prehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Surgery According to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Pathway for the Improvement of Postoperative Outcomes: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR research protocols 2017; 6: e199.

- Sugarbaker PH: Improving oncologic outcomes for colorectal cancer at high risk for local-regional recurrence with novel surgical techniques. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology 2016; 10: 205-213.

- Nordlinger B, et al: Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long-term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology 2013; 14: 1208-1215.

- Van Cutsem E, et al: Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2009; 360: 1408-1417.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(3): 7-12.