It is largely unknown: interstitial cystitis. However, non-infectious chronic inflammation of the urinary bladder wall is associated with painful symptoms, concomitant diseases and psychological distress.

The first guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis has been in effect since fall 2018 [1]. It is aimed at general practitioners, urologists, gynecologists, internists, pain therapists and psychosomatics and is intended to contribute to a better quality of care for those affected.

High number of unreported cases

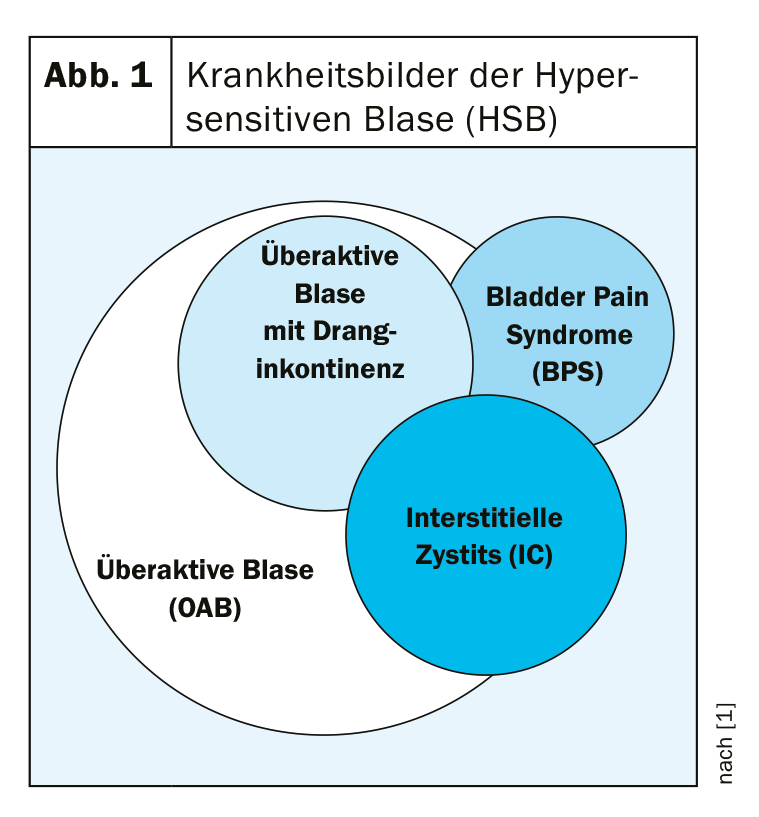

Although no worldwide definition exists, interstitial cystitis (IC) is understood as a non-infectious chronic urinary bladder infection symptomatically manifested by pain, pollakiuria and nocturia. Symptoms occur in varying degrees and combinations. The diagnosis of bladder pain syndrome (BPS) is not sufficient here, as it focuses too much on pain, which does not do justice to the clinical picture of IC. However, due to the sometimes close overlap of different clinical pictures, it is not so easy to distinguish IC from other bladder diseases (Fig. 1).

In principle, IC can occur in any age group, with the highest prevalence found in middle-aged people. Women are affected about nine times more often than men. However, in the absence of epidemiological studies, no precise data exist. The number of unreported cases is high.

It is also unclear how an IC is created in the first place. Various etiopathogenetic factors are discussed. The focus is on possible damage to the urothelium: frequent bladder infections alter the GAG layer, urinary bladder permeability, and urothelial homeostasis. As a result, irritating substances from the urine penetrate the submucosa and deeper layers of the urinary bladder wall. This destructive process may even lead to loss of the urothelium. The defective urinary bladder mucosa evokes increased urinary bladder sensation and pain.

Doctors marathon increases suffering

It can take up to nine years for affected patients to receive a diagnosis of IC. Misdiagnosis is not uncommon, especially in the early stages of the disease. This marathon of doctors is stressful and can lead to sufferers feeling like malingerers, becoming lonely and even developing depression. To make matters worse, IC patients often suffer from concomitant diseases such as fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, psychological disorders and other neurological, functional somatic or rheumatic complaints.

Therefore, it is all the more important that with the S2k guideline of the German Urological Society a consensus now exists on how IC can be diagnosed and treated.

How to diagnose?

As with other diseases, the S2k guideline recommends starting the diagnosis with a comprehensive medical history. Questionnaires such as the ICSI/ICPI index (micturition frequency, urinary bladder discomfort), the PUF questionnaire (dypareunia, pelvic pain) and the Bladder Pain/IC Symptom Score (BPIC-SS) provide support. Documentation forms in the form of a pain diary or a micturition-drinking log are also helpful. The physical examination focuses on the genital area. In addition, a urine sample should be taken. Additional investigations include urosonography, cystoscopy and, in men, uroflowmetry. If needed, hydrodistension, flow EMG, or potassium chloride testing may be considered to elicit increased pain sensitivity. Not crucial for the diagnosis, but additionally to be considered is a biopsy of the urinary bladder wall. However, because mast cells are involved in diverse inflammatory processes, this method is not unique in determining an IC. A stool sample, which provides information about the intestinal flora, also represents a complementary medical option. No biomarkers are currently known, although research is being conducted in this regard.

The diagnosis also includes the exclusion of a whole range of differential diagnoses. These include:

- Muscoskeletal disorders (e.g., pelvic floor dysfunction, fibromyalgia, hernias, chronic back pain, malignancies).

- Gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., CED, irritable bowel syndrome, small and large bowel stenosis, malignancies).

- Gynecological diseases (e.g., endometriosis/adenomyositis, pelvic varicosis, cervical stenosis).

- Urological diseases (e.g. bladder dysfunction, chronic urinary tract inflammation, prostatitis, malignancies)

- Neurogenic causes (e.g., genital herpes, neuralgia, varicella zoster).

- Mental disorders (e.g., affective, schizophrenic, somatoform disorders).

Multimodal treatment!

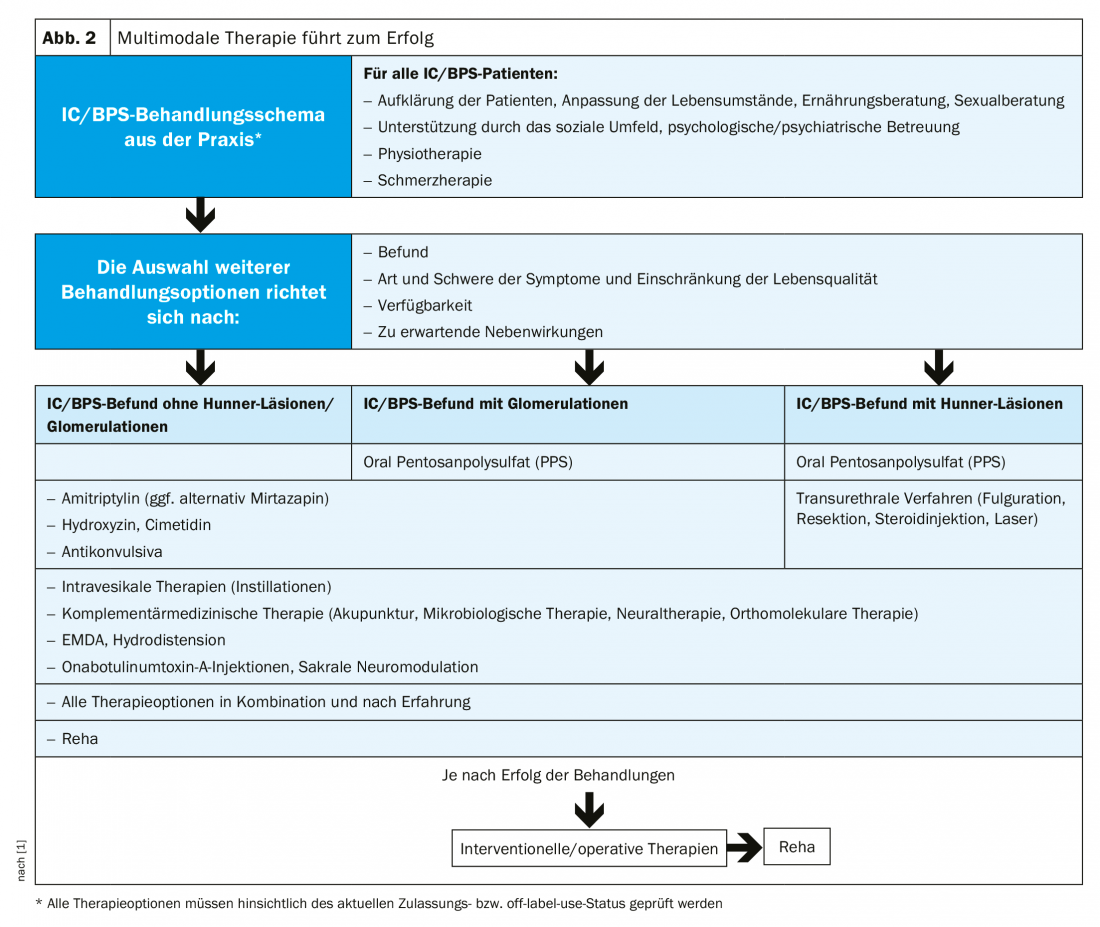

IC is not curable. However, the progression of the disease can be slowed down and the symptoms alleviated. Appropriate therapy should be interdisciplinary and multimodal, taking biopsychosocial aspects into account (Fig. 2). The first step is a change in lifestyle. Wardrobe, sexuality and sports are to be arranged in such a way that there is no worsening of the symptoms. Stress and cold have a negative effect, while bladder training is said to have some efficiency. Because food intolerances are often associated with IC/BPS symptoms, special attention must be paid to diet. Due to their low histamine content, non-fermented, fermented or microbially matured foods are preferable. Similar to IBS, a low-FODMAP diet may prove helpful. Psychosomatic symptoms should be alleviated by psychological or psychiatric care, and the patient’s social environment also plays an important role. Pelvic floor dysfunction, common in IC, can be treated with physical therapy.

Currently, only pentosan polysulfate (PPS) is approved as an oral drug therapy for IC in Europe. The active ingredient repairs the GAG layer of the urothelium, preventing substances that are toxic or irritating to the urinary bladder wall from penetrating. PPS also promotes blood flow to the urinary bladder. The effect usually occurs after three to six months, whereby the earlier the start of therapy, the better!

Off-label, other agents may be considered. Amitriptyline, by inhibiting serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake, modifies CNS pain transmission and reduces mast cell activation, resulting in decreased urination and pain. An alternative to amitriptyline is the tetracyclic antidepressant mirtazapine, which, unlike amitriptyline, has no anticholinergic side effects. Hydroxyzine also inhibits mast cell activation and has anticholinergic, anxiolytic, and analgesic effects. Studies showed a reduction in pain and nocturia in IC patients treated with the histamine-2 receptor antagonist cimetidine. This effect may be explained by the fact that cimetidine inhibits the overexpression of H1 and H2 receptors, purinergic P2X receptors, and cholinergic muscarinic receptors observed in IC. Montelukast, which is approved for asthma, also showed efficacy in IC by reducing mast cell-induced inflammation in a small study. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5) have a relaxing effect on the smooth muscle cells of the urinary bladder, although the cause of action is not yet clear. The calcium channel antagonist nifedipine also proved effective in the treatment of IC. However, prospective randomized trials are still lacking.

The S2k guideline also recommends adequate pain therapy. The patients’ pain should be relieved, and the ill-considered use of poorly effective painkillers should be avoided. Currently, there is no treatment consensus regarding IC, but experts refer to different groups of drugs that can also be used in combination. Depending on severity and patient response, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, novamine sulfone, and opioids may be used.

Furthermore, the use of muscle relaxants (e.g., tizanidine), alpha blockers (e.g., tamsulosin), and anticonvulsants (e.g., pregabalin) is possible.

Systemic side effects can be circumvented by intravesical forms of treatment. However, disadvantages of the therapy, in which high drug concentrations are introduced directly into the urinary bladder, are the risk of infection, invasiveness, and high costs.

Complementary medicine procedures such as acupuncture, neural therapy, microbiological therapies or micronutrient substitution are another option. If none of the therapies is crowned with success, surgery remains. An accompanying measure is always treatment in specialized urological rehabilitation centers. Ultimately, the goal remains to protect the IC sufferer from the threat of incapacity and/or social isolation.

Literature:

- German Society of Urology, ed.: S2k-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Interstitiellen Cystitis (IC/BPS), Langfassung, 1. Auflage, Version 1. 2018.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(5): 39-41