In November 2015, the new guidelines on cardiopulmonary resuscitation were presented. In it, especially – compared to the previous version – elements of the rescue chain are improved. Unconsciousness and absent or abnormal breathing signify cardiovascular arrest. A defibrillator should be used as soon as possible, if available. First responders should begin resuscitation as soon as possible. Availability of public and in-house defibrilators needs to be increased to achieve early defibrillation within 3-5 minutes.

In November 2015, the new American Heart Association (AHA) and European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines on cardiopulmonary resuscitation were presented [1,2]. Both guideline variants are based on a broadly supported scientific consensus of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR), a worldwide association of national and international resuscitation organizations.

Of course, it is very unfortunate when two Guideline variants face each other, because this can potentially lead to different doctrinal statements and confusion. Although the differences are unlikely to be relevant to daily practice, the Swiss Resuscitation Council (SRC) issues binding teaching statements throughout Switzerland, focused on a uniform algorithm for Basic Life Support (BLS) and Basic Life Support (BLS), respectively, in order to avoid uncertainties. automated external defibrillation (BLS/AED).

Recognize emergency quickly and resuscitate quickly

Today’s cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was born in 1960. The ILCOR was founded in 1992 and international guidelines of the ILCOR were published for the first time in 2000. The 2010 resuscitation guidelines brought a focus on chest compressions or chest compressions in addition to a major simplification of the BLS/ALS algorithm. Aside from minor changes, the content of the 2010 BLS/ALS algorithms was essentially confirmed with the new 2015 resuscitation guidelines.

The important innovation of the 2015 Guidelines can be found in the improvements of elements of the rescue chain. This means that important concerns, such as those called for in the “Guidelines on Rescue in Switzerland” or in the article “Resuscitation by First Responders” by the FMH, are now also supported by international guidelines [3,4].

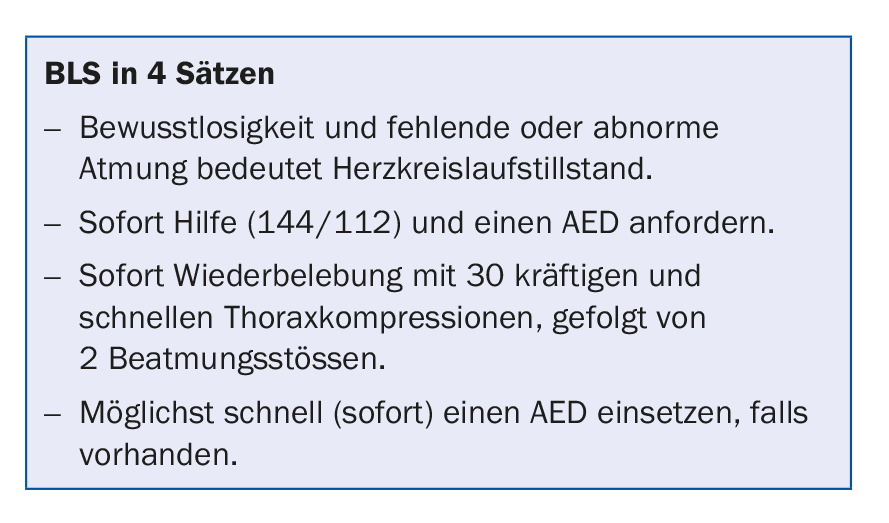

In terms of content, four goals are to be achieved to ensure the best possible chances of survival:

- Rapid detection and emergency call

- Rapid resuscitation

- Rapid defibrillation

- Optimal post reanimation phase

Recognize key symptoms correctly

Recognizing an emergency situation, especially circulatory arrest, is extremely challenging. Of course, the ideal situation would be to correctly interpret the symptoms of impending circulatory arrest even before the patient suffers it. A first responder/emergency witness and the dispatcher at an emergency medical center (SNZ) must both quickly make the diagnosis to activate the rescue chain. A pulse test has been shown to be an inaccurate test method, and even a gasp (up to 40% of patients in circulatory arrest exhibit one) can be misleading for detecting circulatory arrest. Key symptoms include sudden loss of consciousness, lack of response to response or pain stimulus, and abnormal breathing.

Resuscitation measures initiated immediately can double to quadruple the chances of survival. Those not trained in resuscitation should at least perform chest compressions, under the guidance of an SNZ dispatcher if necessary, until professional help arrives.

Availability of and access to public and in-house AEDs must be increased to achieve early defibrillation within 3-5 minutes. This can improve the survival rate to 50-70%. Standards for the post-resuscitation phase help when primary resuscitation measures are unsuccessful (e.g., airway management).

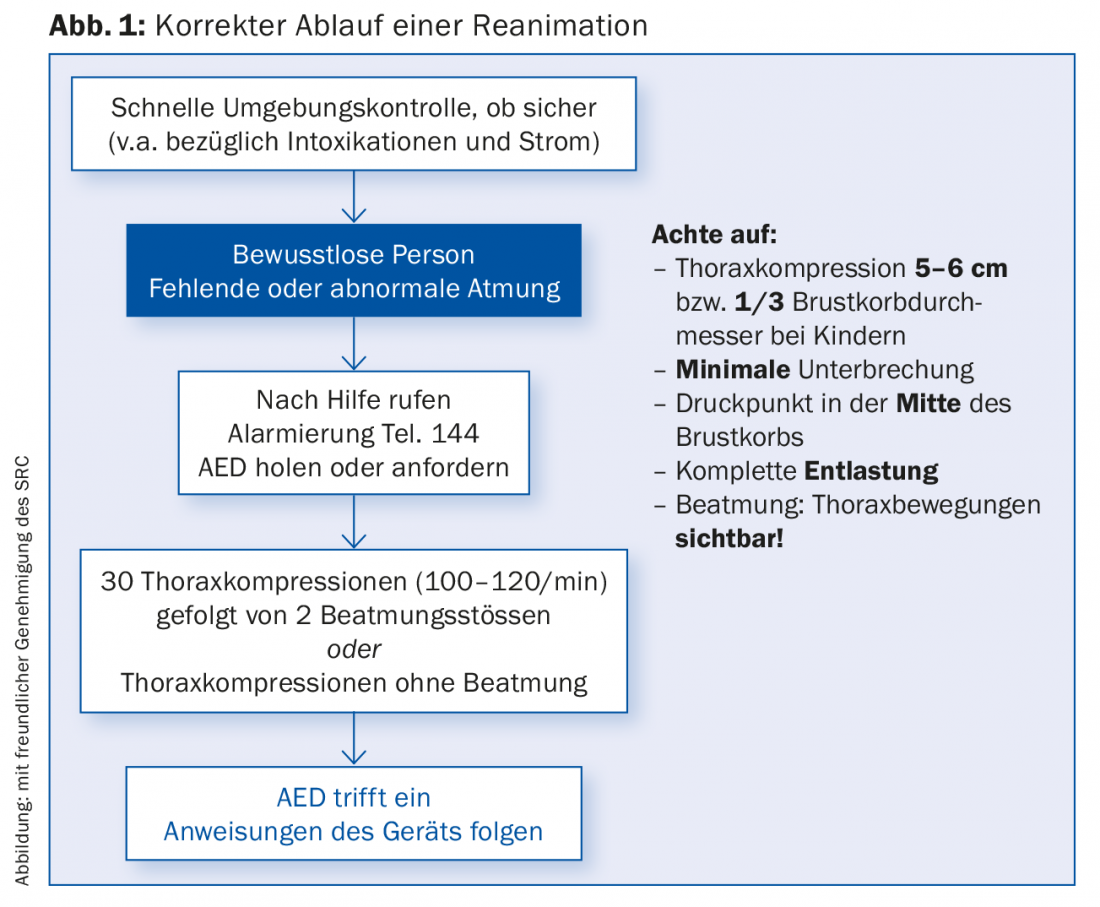

Improved safety and increased rea measures

The SRC’s BLS procedure (Fig. 1) shows step-by-step procedures and provides reassurance to the untrained responder and emergency witness, as well as the trained responder. In terms of content, the BLS process has remained essentially the same. The few innovations are highlighted below.

- Environment control: The first item is a short environment control. This is to emphasize the importance of assessing your own safety first and foremost.

- Assessment: When assessing a motionless person, the assessment of consciousness and respiration can be performed simultaneously. Only a professional may and should perform a pulse check (carotid artery, maximum 10 seconds), therefore this point is not mapped in the general BLS algorithm.

- Circulatory arrest: an unconscious person with absent or abnormal breathing has circulatory arrest. The importance of recognizing gasping as abnormal breathing and thus diagnosing circulatory arrest is emphasized.

- Depth of chest compression and compression frequency: After alerting (144) and requesting an AED where possible, resuscitation must begin immediately. The ultimate goal is good cardiac massage with strong and rapid chest compressions. The exact specifications for depth (5-6 cm or one third of the chest diameter in children) and compression frequency of 100-120/min are new. However, priority is given to good cardiac massage with at least 5 cm compression depth and minimum frequency of 100/min.

- Ventilation by trained rescuers: A rescuer trained in resuscitation should provide ventilation (ratio of chest compressions:breaths = 30:2); laypersons should provide chest compressions alone.

- Immediate AED use: If an AED/defibrillator arrives, it should be used immediately. BLS AED measures should be continued until professional help arrives.

Training of the general population

Only if the BLS-AED algorithm can be widely trained in the population can the chain of rescue truly be improved. Ideally, the curriculum should already be implemented in schools, as in the canton of Ticino. However, this still requires a great deal of education and persuasion to motivate the key decision-makers. Yet these days, BLS AED training is simple and can be learned quickly. Medical professionals should acquire and regularly review BLS-AED skills.

Literature:

- American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015 Nov 3; 132(18 Suppl 2).

- European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015, Resuscitation 95 (2015).

- FMH mission statement on ambulance services in Switzerland, Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 2010; 91: 33.

- Resuscitation by first responders. Swiss Medical Journal 2015; 96(33): 1124-1126.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(7): 29-31