At a symposium on cardiac arrhythmias at the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, the epidemiology, diagnostics and risk assessment of atrial fibrillation were discussed. In addition, the study situation regarding direct oral anticoagulants was discussed and the current situation regarding antidote development was addressed. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages of frequency and rhythm control were the focus of interest.

Atrial fibrillation (VHF) is an absolutely arrhythmic atrial (tachy) arrhythmia lasting more than 30 seconds. Often there is irregular flickering of the baseline, P-waves are not detectable. Surface ECG shows irregular RR intervals (arrhythmia absoluta) without repetitive pattern. Hospitalizations are common in VHF and the risk of death is significantly increased (by 50% in men and 90% in women according to the Framingham cohort [1]). There is also a risk of cerebral stroke (including hemorrhage), which is then usually particularly pronounced in terms of severity. Overall, men are affected slightly more often than women and the prevalence increases sharply with age. The clear number 1 predisposing factor is hypertension.

In cases of VCF, correct diagnosis should be made first, followed by prevention of thromboembolic events. In addition to the treatment of concomitant cardiovascular diseases (central is the control of hypertension), the reduction of symptoms as well as rhythm or frequency control are therapeutic goals. According to Prof. Dr. med. André Linka, Head of Cardiology at the Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, the following can be said about the diagnosis and initial management: If VCF is suspected, the ECG is used for documentation (in the case of antiarrhythmic therapy, regular ECG checks must also be carried out during the course). Symptoms can be quantified using scores (e.g., EHRA score). In addition, a detailed arrhythmia-specific history and physical examination should be performed. “Basically, every patient also needs an echocardiogram,” Prof. Linka said.

Risk assessment: balancing stroke and bleeding risk

For initial simple assessment of thromboembolic risk in VHF, the CHADS2 score is used. If this is at least 2 points, the use of oral anticoagulation (OAC) with a target INR of 2.0-3.0 is indicated. The risk of bleeding should always be considered (quantifiable with the HAS-BLED risk score). If the CHADS2 score is less than 2, the CHA2DS2-VASc score is added. This allows a somewhat finer differentiation in patients at low risk of stroke and may allow better risk stratification. At a score of 1, either OAK or aspirin 75-325 mg/d is used, with OAK being preferable in all cases. If a value of 0 is obtained, either no antithrombotic therapy is required (preference) or aspirin is used at the above dose.

Study situation on anticoagulation

According to Thomas Lehmann, MD, Senior Physician at the Center for Laboratory Medicine, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major problem of the modern healthcare system: In Europe alone, a good half million deaths per year are associated with VTE – mortality is thus many times higher than, for example, for breast or prostate cancer (approx. 60-90 000) [2].

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) may be considered standard therapy for VHF. A review of the studies (RE-LY [3], ROCKET-AF [4], ARISTOTLE [5], ENGAGE AF [6]) shows that DOAKs are not inferior to vitamin K antagonists (VKA) in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism and are even superior in some cases. In addition, fewer patients experience intracranial hemorrhage with DOAKs than with warfarin. Severe bleeding also occurs significantly less frequently, except with rivaroxaban and dabigatran 2× 150 mg/d.

In preventing recurrence of VTE or VTE-associated death in patients with acute VTE, DOAKs are noninferior to conventional therapy (VKA, preceded by heparin) and tended to result in fewer bleeding events. The studies in question are called Hokusai-VTE [7], AMPLIFY [8], EINSTEIN-DVT [9], -PE [10] and RECOVER [11], -II [12]. Because rivaroxaban and apixaban differed significantly from comparators in the incidence of major bleeding-as shown by AMPLIFY and EINSTEIN-PE (as well as EINSTEIN’s pooled analysis)-there is an overall improved net clinical benefit for these two. Extension studies such as AMPLIFY-EXT [13], EINSTEIN [9], and RE-SONATE [14] also demonstrated a significant benefit of prolonged VTE prophylaxis with DOAK (compared with placebo). This either did not increase the rate of major bleeding at all or increased it only slightly. In this regard, apixaban showed the best benefit-risk profile in long-term VTE prophylaxis.

DOAK and acute bleeding

If one wants to treat (cerebral) hemorrhagic complications under apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban, the problem arises that so far no specific antidote is available. In April 2014, the so-called RE-VERSE AD study started, which is currently recruiting patients in more than 35 countries worldwide. In it, idarucizumab is being studied to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran (interim data published in late June 2015 [15] are promising). Previously, a study presented at the 2013 AHA Congress demonstrated that idarucizumab injection had a rapid, complete, and sustained effect against dabigatran anticoagulation in healthy volunteer participants (visible in the dTT[diluted thrombin time] measurement).

A promising solution is also offered by the new antidote Andexanet alfa, which acts as a kind of “bait” for Factor Xa inhibitors in the blood. The recombinant molecule resembles human Factor Xa, but does not exhibit its clotting function. It thus “attracts” the anticoagulant agent circulating in the blood and binds to it with high affinity and competitively. Inhibition of clotting is quickly reversed because the inhibitors are no longer able to dock to and block human factor Xa. Andexanet alfa antagonizes the action of the three known factor Xa inhibitors and enoxaparin thus rapidly and without thrombotic events. A large phase III program called ANNEXA™ is currently ongoing (new results on ANNEXA-R were presented at the ACC Congress, see CARDIOVASC 3/2015).

Rhythm vs. frequency control

According to Holger Stöckel, M.D., senior physician in cardiology at Winterthur Cantonal Hospital, the goal of drug therapy for VHF can be rhythm or frequency control. The AFFIRM trial showed that rhythm control did not confer a survival advantage over rate control. Both vascular and cardiac deaths occurred with equal frequency in both groups, and the rate of death from noncardiovascular causes was even significantly increased. “Presumably, the more frequent use of antiarrhythmic drugs in the rhythm-maintenance group was the cause of the increased noncardiovascular mortality,” Dr. Stoeckel said. A follow-up several years later therefore concluded that sinus rhythm, but not antiarrhythmic drug use, was associated with a lower risk of mortality. Preservation of sinus rhythm without use of the potentially dangerous antiarrhythmic drugs is probably better, he said.

Before initiating drug therapy, it is always recommended to first clarify possible cardiac diseases. Treatment then depends on the underlying disease and symptoms. In principle, you should only use medications that you know well (beta-blockers as a basic medication). The patient must be informed about the possible side effects. Progress monitoring also allows the therapy to be adjusted.

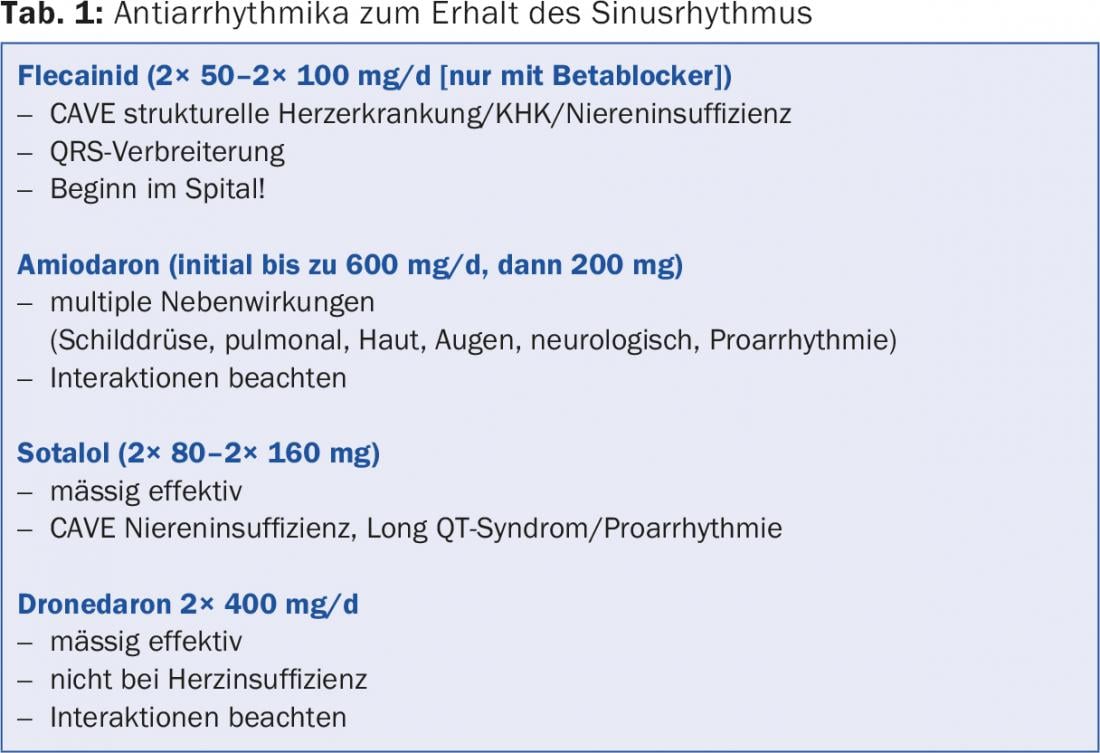

For first events, conversion is usually the goal. For symptom-free patients, frequency control may be sufficient (drugs approved for this purpose are metoprolol, bisoprolol, verapamil, diltiazem, and digoxin). In the event that conversion is performed for a new-onset VCF, there are two options: Hemodynamically unstable emergency patients and physician-selected candidates undergo electrical cardioversion. Hamedynamically stable patients receive antiarrhythmic drugs depending on the presence and severity of structural heart disease. Detailed information on this can be found in the ESC Guidelines 2012 [16]. Flecainide, amiodarone, sotalol, and dronedarone are used to maintain sinus rhythm. Important aspects in the handling of the drugs are shown in Table 1.

In symptomatic patients with atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation may be offered after ineffective/badly tolerated antiarrhythmic drug therapy or as an alternative. Pulmonary vein isolation is performed by radio-frequency or cryoablation in patients with paroxysmal and also persistent atrial fibrillation. At an experienced center and under careful assessment of the benefit-risk profile (age, concomitant diseases, etc.), atrial fibrillation ablation yields good results: In a randomized study from 2014 [17], (radiofrequency) ablation performs significantly better as first-line therapy compared to antiarrhythmic drugs. The primary end point was the time to the first documented atrial tachyarrhythmia of more than 30 sec. Duration. Secondary endpoints included the recurrence of such events.

In rare cases (1%), pericardial tamponade requiring drainage may occur. TIA or stroke also occurs in approximately 1% of cases. A feared complication, atrioesophageal fistula, is found very rarely at 0.03%. Relapses, on the other hand, occur in 20-50% of cases.

Source: “Rund ums Vorhofflimmern”, Symposium Herzrhythmusstörungen II, 11 June 2015, Winterthur

Literature:

- Benjamin EJ, et al: Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998 Sep 8; 98(10): 946-952.

- Cohen AT, et al: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 2007 Oct; 98(4): 756-764.

- Connolly SJ, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009 Sep 17; 361(12): 1139-1151.

- Patel MR, et al: Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011 Sep 8; 365(10): 883-891.

- Granger CB, et al: Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011 Sep 15; 365(11): 981-992.

- Giugliano RP, et al: Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013 Nov 28; 369(22): 2093-2104.

- Hokusai-VTE Investigators: Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013 Oct 10; 369(15): 1406-1415.

- Agnelli G, et al: Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013 Aug 29; 369(9): 799-808.

- EINSTEIN Investigators: Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010 Dec 23; 363(26): 2499-2510.

- EINSTEIN-PE Investigators: Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2012 Apr 5; 366(14): 1287-1297.

- Schulman S, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2009 Dec 10; 361(24): 2342-2352.

- Schulman S, et al: Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysis. Circulation 2014 Feb 18; 129(7): 764-772.

- Agnelli G, et al: Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013 Feb 21; 368(8): 699-708.

- Schulman S, et al: Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013 Feb 21; 368(8): 709-718.

- Pollack CV, et al: Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. NEJM 2015 June 22. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502000 (Epub ahead of print).

- Camm AJ, et al: 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 2012; 33: 2719-2747.

- Morillo CA, et al: Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (RAAFT-2): a randomized trial. JAMA 2014 Feb 19; 311(7): 692-700.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(9): 40-42