There are 400 million COPD sufferers worldwide. It is the fourth leading global cause of mortality. At the Internal Medicine Update Refresher 2017 in Zurich, the latest findings for evidence-based diagnostics and therapy were presented.

There are 400 million COPD sufferers worldwide. It is the fourth leading cause of global mortality [1]. There are 300,000 sufferers in Switzerland, with a prevalence of 2.5% in 30-39 year olds and 8% in >70 year olds. In addition to tobacco smoking, risk factors include dust particle exposure (e.g., in agriculture) and smoke particle exposure from wood-burning stoves. For the most specific treatment possible, tailored to individual needs, the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines have been adapted to the current state of research. The importance of bronchodilators (LAMA = long-acting anticholinergics/LABA = long-acting β-2-agonists) has increased significantly in recent years, whereas inhaled steroids (ICS) are used less frequently than in the past, reported Prof. Robert Thurnheer, MD, Head of Medical Diagnostics, Münsterlingen Cantonal Hospital.

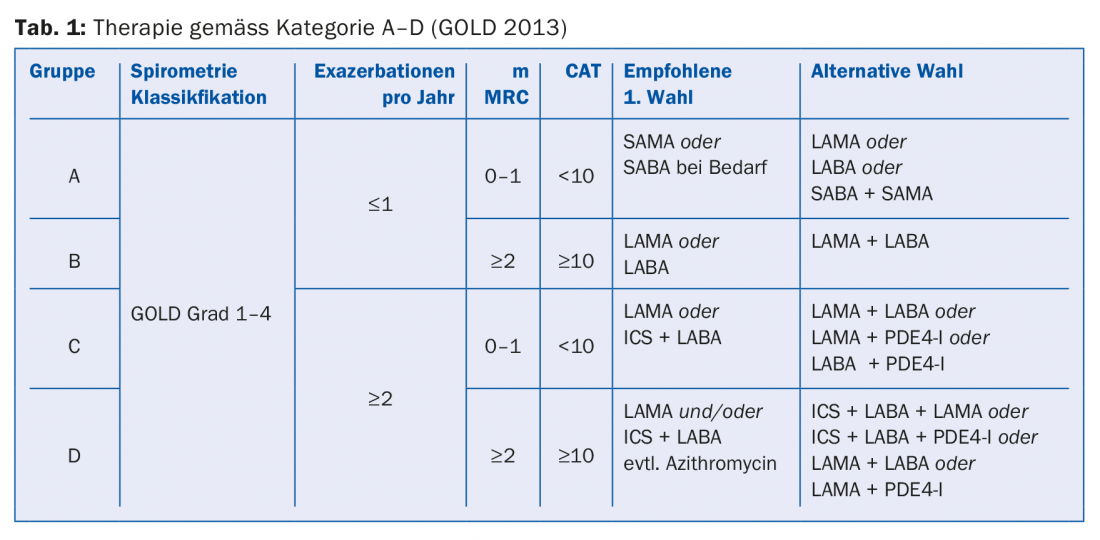

Phenotyping according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)

The currently valid classification A-D (tab. 1) is no longer based on lung function but on symptoms and exacerbation risk and serves as a basis for evidence-based therapy. The “CAT” (COPD Assessment Test) and “mMRC” (Dyspnea Screening) questionnaires are used as diagnostic tools. For group A patients (few symptoms, no exacerbations), a bronchodilator (LABA or LAMA) may be used. Group B patients (symptoms but no exacerbations) should also receive a bronchodilator. If symptoms persist, switch to a combination drug (Anoro® or Spiolto® or Ultibro®). In case of increased exacerbations, the combination with an inhalable steroid (ICS) is recommended according to GOLD guidelines. In group C patients (exacerbations), the first choice is monotherapy with LAMA. If exacerbations continue to occur, switch to combination therapy: LABA and LAMA or LABA and ICS. Therapy of group D can also be performed according to a stepwise scheme (Tab. 1), although Professor Thurnheer advised caution regarding prophylactic use of macrolides due to side effect risks (e.g., sensorineural hearing loss, long-QT syndromes, resistance, lack of long-term data).

Bronchodilation: what is the therapeutic benefit and how to achieve the best effects?

In summary, the following arguments support the efficacy of bronchodilation (LAMA, LABA): improvement in lung function [2], decrease in hyperinflation [3], improvement in symptoms [4], decrease in exacerbation rate [4]. For Group A and B, it does not matter whether LABA or LAMA is used first. For group C and D it is recommended to use LAMA first. In the POET study, LAMA (Spiriva®) was superior to salmeterol (Serevent®) in preventing exacerbations [5].

According to new evidence, starting therapy as early as possible (i.e., in pulmonary functional stage 2 = target FEV1 50-80%) has a positive effect; for example, studies showed that when tiotropium (Spiriva®) the decrease in FEV1 (Forced Expiratory Volume in the first second of expiration) after two years is less pronounced than in the placebo condition [6] and patients are also less affected by “hyperinflation” (dynamic overinflation) at an early stage during exercise.

Several clinical studies [7,8] have shown that combination preparations of LAMA and LABA (Anoro®, Spiolto®, Ultibro®) are superior to monotherapy (LAMA or LABA) with regard to the following targets: better lung function, fewer symptoms, reduction in the exacerbation rate. In the SPARK study, for example, Ultibro® was shown to achieve better effects than the respective single agents [7]. The use of a combination drug is recommended mainly for COPD patients with insufficient response to low-dose monotherapy with LAMA or LABA [9] and for patients with severe COPD and dyspnea symptoms [10,11].

According to the compendium, monotherapy should always be carried out first and a combination preparation should only be used if there is a lack of effect, but according to the guidelines, primary treatment with a combination preparation is also permitted. In addition to efficacy, handling can also play a role in the decision as to which of the three combination preparations (Anoro®, Ultibro®, Spiolto®) is used.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS): controversy regarding therapeutic benefit

Unlike asthma, where inhaled steroids (ICS) are the basic treatment, the use of ICS in COPD is controversial.

In the FLAME study [12], combined bronchodilators (LABA+LAMA) achieved significantly greater reductions in exacerbations compared with LABA+ICS. In the WISDOM study [8], omission of ICS did not result in an increase in the frequency of exacerbations, although patients without ICS showed worsening in FEV1 values over the long-term [8]. In a subgroup of COPD patients with eosinophilia (>2% blood eosinophilia) and increased risk of exacerbation, ICS caused a reduction in the rate of exacerbation [13,14]. In COPD patients with increased cardiovascular risk, according to the SUMMIT study (n=16 485, 43 countries), the use of ICS did not reduce mortality rates, but slightly reduced the “rate of decline” in lung function [15].

The effects of combined use of bronchodilators and ICS (“triple therapy”) can be summarized as follows according to current research [16]: no effect on mortality and cardiovascular endpoints, little effect on lung function, some exacerbation reduction [17,18], but significantly more pneumonias (side effect of ICS).

Therapy of advanced COPD: “Treatable traits” and behavioral interventions.

The preparation Prolastin® can be used as a substitution in the case of a deficiency of α-1-antitrypsin (protease inhibitor), although positive effects have so far only been shown for lung structural criteria. Daxas® (active ingredient: roflumilast) leads to a slight improvement in lung function and a slightly significant decrease in the rate of exacerbations, although side effects may also occur: Weight loss, increased risk of sleep disturbances, mood swings [19]. Mepolizumab (e.g. Nucala®) is already successfully used for asthmatics with eosinophilia and can also be used in COPD and eosinophilia to achieve positive effects in terms of reducing the exacerbation rate, although the drug is not yet approved for COPD patients for this indication [20].

Regarding oxygen therapy in severe hypoxemia, Professor Thurnheer mentioned that a survival benefit becomes significant only after about four years of therapy and that no effects were seen in only mild hypoxemia with respect to subjective quality of life, risk of hospitalization, and risk of exacerbation [21].

With regard to behavioral interventions, in addition to support for smoking cessation, physical therapy and nutritional counseling (often caloric malnutrition due to emphysema and muscle wasting) have proven effective. In the event of exacerbations, the creation of an action plan is recommended. For example, one should have systemic steroids (five daily doses of 40 mg each) [22] when traveling and antibiotics (e.g., co-amoxicillin, tetracycline, and others) in reserve in case of bronchial symptoms. Other measures mentioned include control of inhalation technique, annual influenza vaccination, and one-time pneumococcal vaccination (Prevenar-13® in children).

Source: Internal Medicine Update Refresher, December 5-9, 2017, Zurich.

Literature:

- Bridevaux P-O, et al: Prevalence of airflow obstruction in smokers and never-smokers in Switzerland. European Respiratory Journal 2010; 36: 1259-1269.

- Tashkin DP, et al: Bronchodilator responsiveness in patients with COPD. European Respiratory Journal 2008; 31: 742-750.

- Dellaca RL, et al: Effect of bronchodilation on expiratory flow-limitation and resting lung mechanics in COPD. European Respiratory Journal 2009; 33: 1329-1337.

- Jones PW, et al: Correlating changes in lung function with patient outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pooled analysis. Respir Res 2011; 12: 161.

- Vogelmeier C, et al: Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD (POET). N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1093-1103.

- Zhou Y, et al: Tiotropium in early-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 923-935.

- Wedzicha JA, et al: Analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 199-209.

- Magnussen H, et al: Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Eng J Med 2014; 371: 1285-1294.

- Donohue JF, et al: Efficacy and safety of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg in COPD. Respir Med 2013; 107(10): 1538-1546.

- Kessler R, et al: Symptom variability in patients with severe COPD; a pan European cross-sectional study. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 264-272.

- Price D, et al: Impact of night-time symptoms in COPD, a real-world study in five European countries. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013; 8: 595-603.

- Wedzicha JA, et al: Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(23): 2222-2234.

- Vedel-Krogh S, et al: Blood Eosinophils and Exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. AJRCCM 2016; 93(9): 965-974.

- Pascoe S, et al: Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 435-442.

- Vestbo J, et al: Fluticasone furoate and vilanterol and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with increased cardiovascular risk (SUMMIT): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1817-1826.

- Vogelmeier CF, et al: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic and Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report : GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1700214.

- Vestbo J, et al: Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY). Lancet 2017; 389: 1919-1929.

- Singh D, et al: Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 936-973.

- Chong J, Leung B, Poole P, Black PN: Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (5): CD002309.

- Pavord ID, et al: Mepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1613-1629.

- LTOT Trial Research Group: A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(17): 1617-1627.

- Leuppi JD, et al: Short-term vs conventional glucocorticoid therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309(21):2223-2231.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(1): 41-43