Metastatic colorectal cancer was the focus of an afternoon symposium in St. Gallen. Significant progress has been made in the field of colorectal cancer therapy in recent years, but this in turn has raised new questions. Should patients with asymptomatic primary tumors be operated on at all if there is no immediate risk of complications? When is there a realistic chance of cure despite liver metastases? And what are the current guidelines regarding RAS testing?

Is it reasonable to remove the (asymptomatic) primary tumor in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and non-resectable metastases? This question was explained by Prof. Ulrich Güller, MHS, FEBS, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen and University of Bern.

To operate or not to operate?

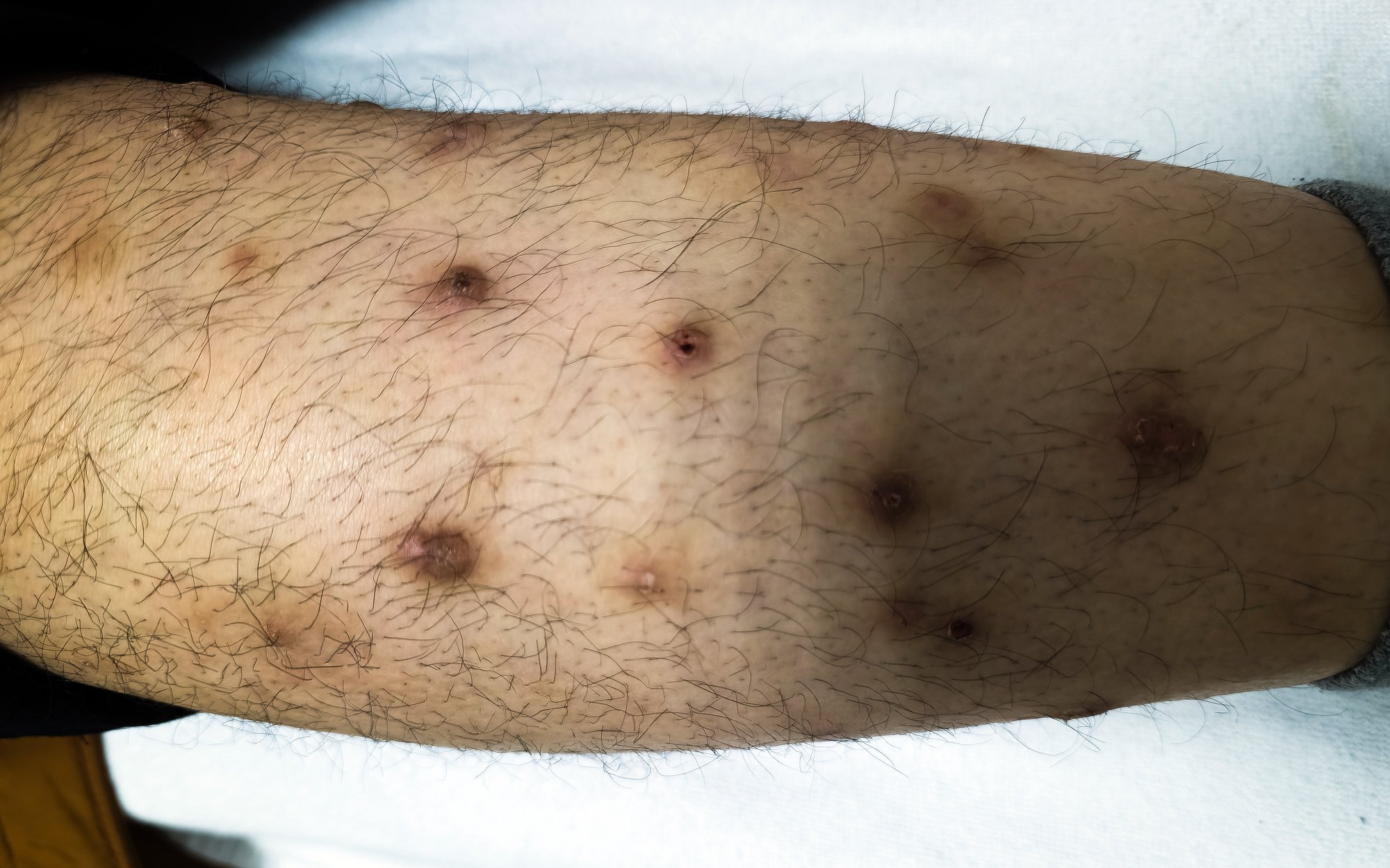

In about 20-25% of all patients diagnosed with CRC, metastases are already present (synchronous metastasis). In more than 70% of affected patients, these metastases are initially unresectable. Proponents of resection of the primary tumor argue that complications such as bleeding or obstruction can be avoided and emergency interventions can be prevented. The argument against resection is that even elective removal of the primary tumor is associated with a certain postoperative morbidity (and mortality), especially in the case of deep-seated tumors, and that surgery may therefore also delay the start of relevant systemic therapy.

A 2009 study evaluated the outcome of patients with synchronously metastatic CRC in whom the primary tumor was not removed after diagnosis [1]. Complications of the primary tumor occurred in only 11% of these patients, and 4% could be treated without surgery. Emergency intervention was necessary in 7% of patients. The “number needed to treat” was 14. Therefore, the current NCCN guidelines (version 2.2015) do not recommend palliative removal of the primary tumor; the experts value the risk of surgery higher than the potential benefits.

But might not removal of the primary tumor also have a positive impact on overall survival? This issue was addressed in a study led by Prof. Güller, which examined data from nearly 38,000 patients with metastatic CRC from the SEER database [2]. Significantly better overall survival was shown in various analyses in patients whose primary tumor was resected. However, the speaker pointed out that there may be a selection bias here, as patients who have undergone surgery tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities, better performance status, and less frequent tumors in the rectum. A 2012 Cochrane Collaboration systematic review showed no statistically significant differences in overall survival, but the included studies were of poor quality [3].

Therapeutic options for resectable liver metastases.

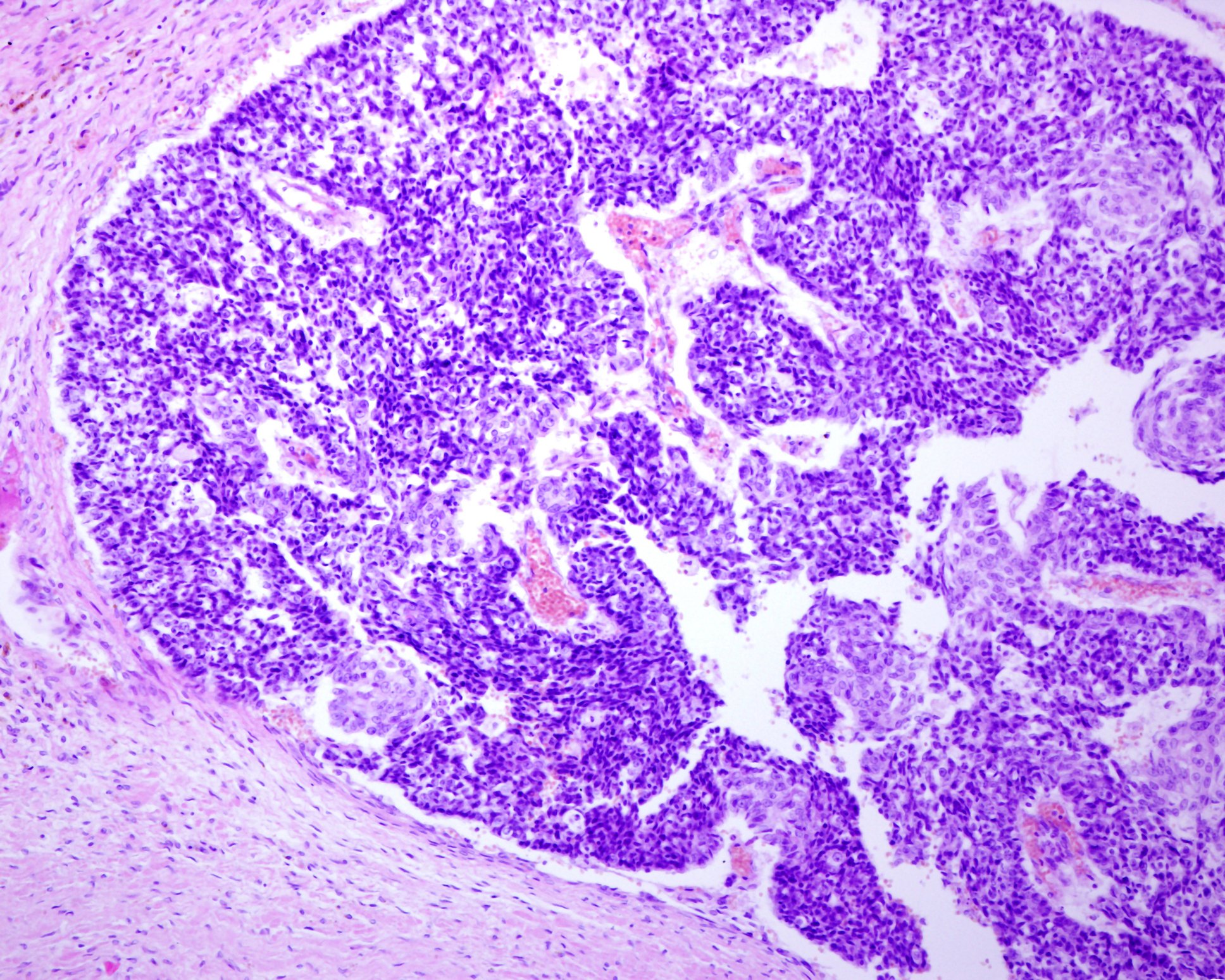

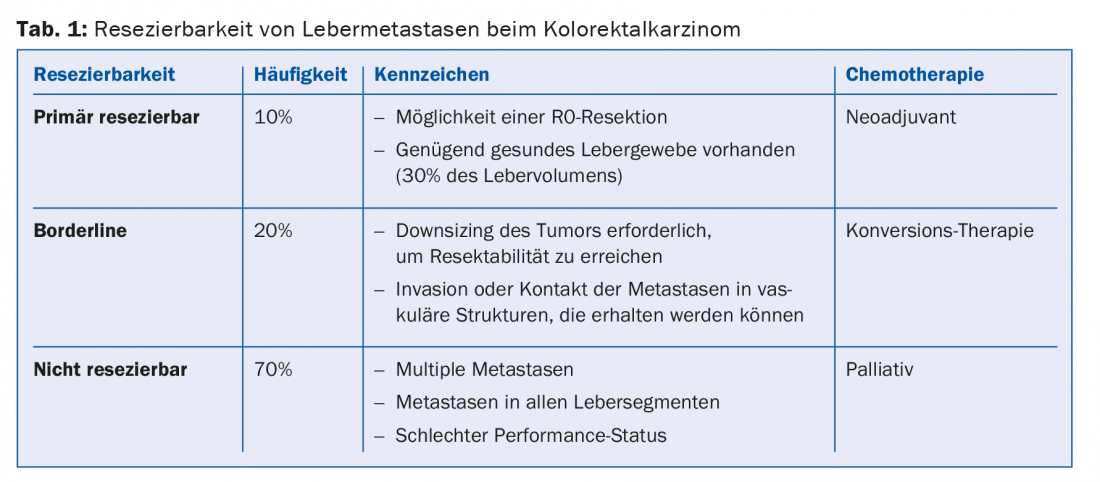

PD Dr. med. Dieter Köberle, Claraspital Basel, provided information on the procedure for patients in whom metastases are limited to the liver. A distinction is made between three situations: primarily resectable, borderline resectable and non-resectable metastases (Table 1). Patients in whom metastases can be resected have a survival advantage.

Any patient with limited liver metastasis should present to a tumor board that includes a liver surgeon. In the tumor board, prognostic factors are examined (e.g., size of the liver after resection, number and size of metastases, vascular supply) and therapy concepts are jointly developed. The term “curative intention” does not mean that a cure is likely, only that it is possible (possibly only in a small percentage of patients).

According to one study, patients with fewer than five liver metastases have a survival advantage when perioperative chemotherapy is given in addition to metastatic surgery [4].

Therapy algorithm in metastatic CRC.

“Today, the median survival in mCRC is about 30 months,” recalled Prof. Dirk Arnold, MD, Freiburg (D). This is a significant improvement when compared to survival 20 years ago. The speaker mentioned three areas where further optimization is possible: Improvements in first-line therapy, exploitation of the possibilities for cure by resection resp. Ablation of metastases and “continuum of care” with optimal therapies even in the second or third line. Trends for prolonged overall survival (OS) have emerged for most first-line therapy regimens with targeted therapies, but there is no evidence (yet).

New rules apply to the use of additional targeted therapies to chemotherapy: Patients are no longer tested only for KRAS but also for additional RAS mutations before any treatment, because for individuals with RAS mutations, therapy with an EGFR or VEGF inhibitor is not only useless but even potentially harmful.

Whether the use of anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF agents is more effective has been investigated in several phase II and III trials (CALGB 80405, FIRE-3, PEAK). In FIRE-3, there was a benefit in terms of overall survival for treatment with cetuximab, whereas no such benefit was evident in CALGB. Explanations for this difference are currently being sought. In the ESMO guidelines, for patients with mCRC and RAS wild-type, all chemotherapy-antibody combinations are considered standard treatments – selection should be made considering clinical and pathologic factors, patient factors, and also patient preference. Although the duration of progression-free survival (PFS) has remained approximately the same in the first-line setting in the various studies conducted in recent years, OS has increased markedly.

“In the future, testing for molecular subtypes will play a much greater role,” predicted the speaker. For example, it appears that the “standards of care” have limited benefit in patients with BRAF mutations. According to Prof. Arnold, the future here lies in treatment without chemotherapy.

Source: 25th Physician Continuing Education Course in Clinical Oncology, February 19-21, 2015, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Literature:

- Poultsides GA, et al: J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(20): 3379-3384.

- Tarantino I, et al: Ann Surg 2014 Nov 4. [Epub ahead of print]

- Cirocchi R, et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 8: CD008997.

- Nordlinger B, et al: Lancet 2008; 371(9617): 1007-1016.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(4): 41-42