Case history: 28-year-old M. Janine, with no family or personal history of atopic disease, had been suffering from a persistent cough for several months, especially at night. Various therapy attempts with antitussives, without or with codeine, homeopathic globules, bioresonance, etc. remained unsuccessful. Due to worsening of symptoms and recurrence of wheezing and mild dyspnea , the patient decided to see a pulmonologist. A metacholine pulmonary test showed mild bronchial hyperreactivity, IgE level was 57 KU/l (normal range), and a phadiatop test for inhalant allergens was negative. A therapy with an inhalable corticosteroid (Symbicort® by means of a turbohaler) was successfully initiated, but the patient discontinued it of her own accord during a two-week stay at the sea when she was free of symptoms. Back at home, the first severe asthma attack occurred during the night. The general practitioner now prescribed the Symbicort® again and gave another bronchospasmolytic (Ventolin®) to be used before the Symbicort inhalation, as well as for the emergency. With this therapy, which the patient did not perform regularly, she was not completely free of symptoms: Especially at night, she was again plagued by a persistent cough. In the meantime, she had a boyfriend and during sleepovers with him, she was symptom-free. She now thought it was an allergy, so she came to see me for further allergy workup.

Allergological clarification

Atopy prick test: all negative; serum IgE levels within normal range at 85 kU/l, SX1 (inhalation screen) negative at <0.35 kU/l.

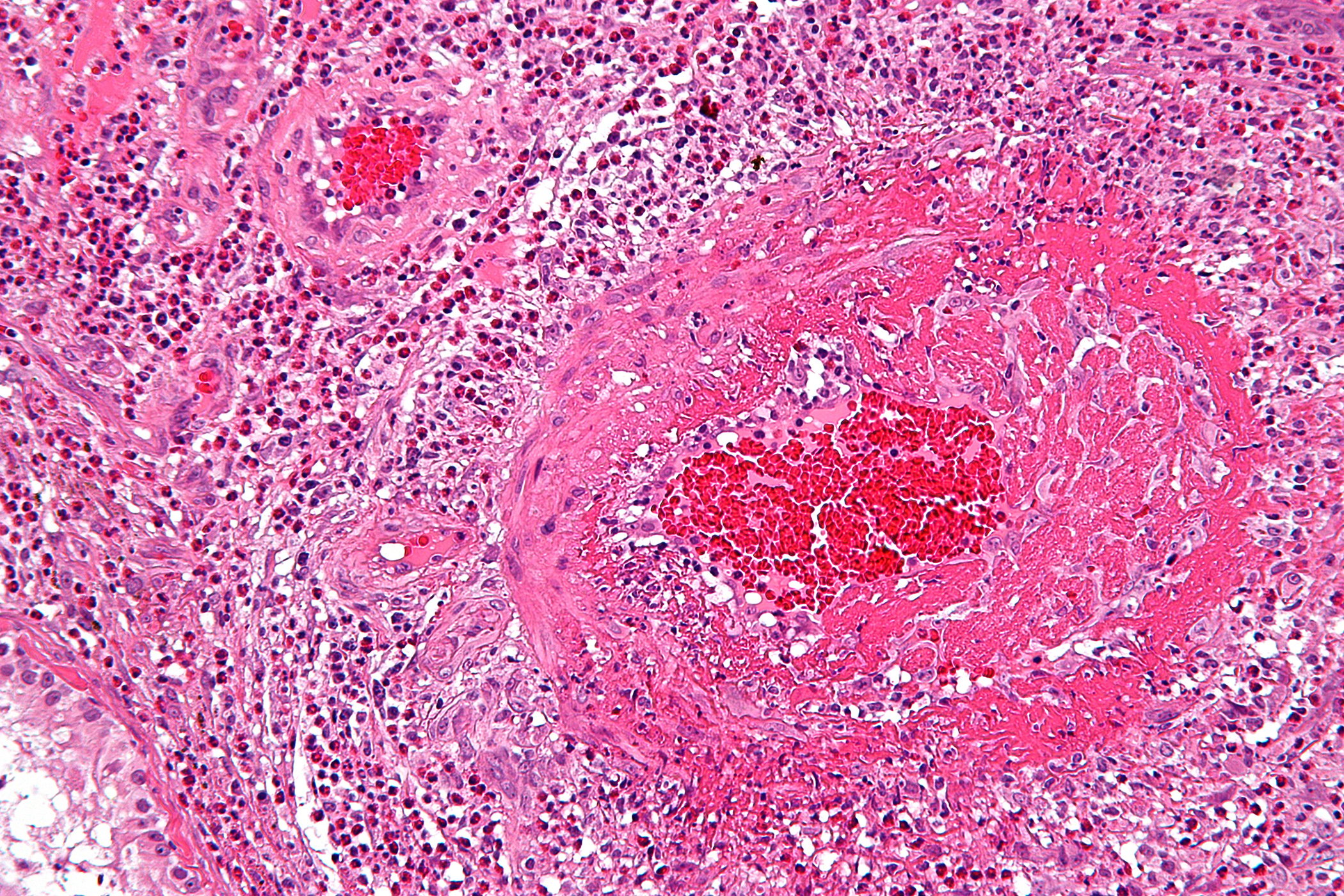

The patient did not keep pets or houseplants (Ficus benjamina), she did not have any particular hobby, and in her opinion there was nothing noticeable in the bedroom. Various scratch (scarification) tests with dust samples from the dust bag, from the pillow, the mattress and the comforter gave a very strong positive immediate reaction with the filling material of the comforter (Fig.1). The label declaration showed that the Mandarin brand quilt contained wild silk (tussah silk) (Fig.2). On the label was the designation “Dream Sleep”. After removal of the blanket, the patient was symptom-free after two days without medication.

Diagnosis

Bronchial asthma allergicum in monovalent sensitization to wild silk.

In search of the triggering allergen in the “wild silk” blankets

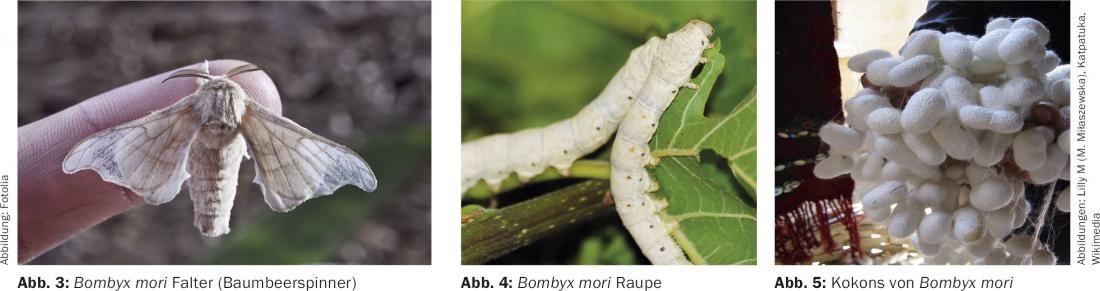

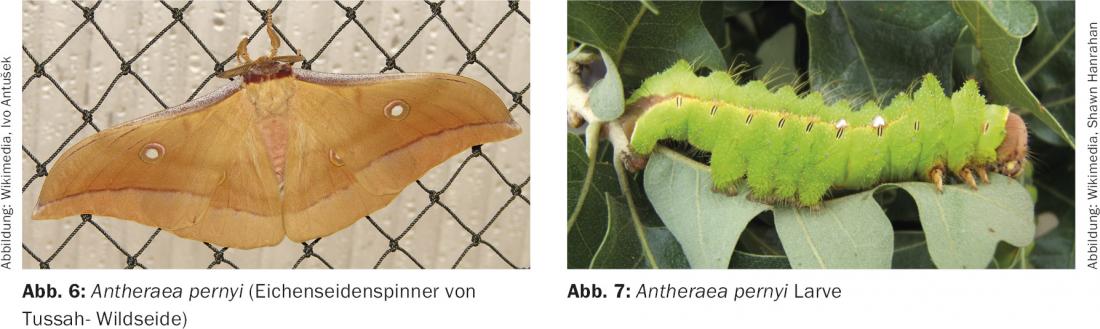

Besides the mulberry silk, made from the cocoons of the silkworm, the larva of the silkworm Bombyx mori, which feed exclusively on mulberry leaves (Fig. 3-5), wild silk, also called tussah silk, is obtained from the cocoons of free-living silkworms, mainly oak silkworms of the genus Antheraea pernyi (Fig. 6-7). (For terms of silk nomenclature, see below).

Since this first case of wild silk allergy diagnosed in the allergy ward in 1979, by February 1982, 26 patients (19 women and 7 men with the relatively high age of manifestation of a mean of 34 years) had been diagnosed with allergic bronchial asthma to wild silk blankets. (More typical case studies in the box). Our first announcement in the Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift [1] generated great interest among the media and blanket manufacturers. Similar cases were soon found in other cantons of Switzerland, in Germany and in Austria. The diagnosis was based, as in the case described above, on the positive scratch tests with the contents of the wild silk blanket of various manufacturers (Mandarin, Brinkhaus AG, Dorseide and Dorberna, Dorbena AG; Patricia and Billerbeck) and – as it turned out in later cases – on a positive intracutaneous test with the silk extract of the Hollister-Stier company. After the number of patients had increased to 50 by the end of 1982 (21 of whom were monovalently sensitized), extensive investigations were carried out in collaboration with Prof. S.G.O. Johannson, Karolinska Institute in Stochkolm, Sweden, elaborate investigations were carried out to find the causative allergen. Morphological-microscopic examination of bed contents from different manufactures, extracts for specific IgE determination were prepared from declared pure wild silks and silks of Bombyx mori, from sericin, the silk glue of Bombyx mori, cocoons and chrysalides [2]. It turned out that the products declared as “pure wild silk” actually consisted of wild silk waste and also contained up to 20% waste from mulberry silk, and that some bedding ingredients were contaminated with an insect of the genus Anthrenus, which – during transport to the silk factories – parasitized the cocoons [2]. A RAST disk (k73, Pharmacia) coupled with the extract from the contents of a wild silk blanket, shipped by us to Stockholm, was thus available for in vitro diagnostics for the first time in 1985. A wild silk extract for prick testing was also prepared in the allergology-immunology laboratory in Zurich.

Accordingly, “wild silk allergy” is partly a sensitization to Bomby mori- and Antheraea and partly to – anthrenus allergens.

The history of silk

According to the website www.seidenwald.de/wissenswertes-ueber-seide/allergiepotential-von-wildseide.html, a Chinese legend tells that silk was discovered in 2640 BC by Xi Ling Ji, the 14-year-old wife of the third Chinese emperor Huang Di (also known as the Yellow Emperor, who had the imposing necropolis of Xi An built). Xi Ling Ji was drinking a cup of tea under a mulberry tree in the palace garden when a silk cocoon fell from the tree into her cup. She and her maids watched in amazement as the cocoon began to dissolve, leaving a long fine thread behind. Xi Ling Ji was enchanted by the beauty and strength of this material, so she had thousands of silk cocoons collected and woven into a cloak for the emperor.

So much for the legend. In fact, silk as a fabric for luxury items has been known in China for 4000-5000 years. Originally only the emperor was allowed to wear this noble material, later also high officials at court. With the development of production technologies, the use of silk spread. At times, silk was also used as a means of payment because of its high value. From about 2000 B.C., China began to trade silk with Western countries as well via the so-called Silk Road, although silk products were always luxury items for wealthy people. The dissemination of the “production know-how” of silk manufacture was thereby forbidden under penalty of death – and could thus be prevented for over 2500 years. It is claimed that around 550 AD two monks managed to smuggle silk cocoons in their walking sticks all the way to Constantinople/Byzantium, which was then the main silk market for centuries. However, it took a good 700 more years (until the 13th century) for the technology of silk production to spread further west. Around 1400, large mulberry plantations were established in Lombardy and then in the 15th century Italy was the leading nation in the production of silk, which had its heyday in the 19th century. Later this became France, which in the 17th century greatly expanded its capacity in silk production. Then, around 1620, the silk weaving district in London was founded by Huguenots who had fled. From the 17th to the 19th century Krefeld was one of the sites of silk production.

From China, silkworm breeding and silk production spread to India, Korea and Japan. Even today, these countries are the world’s most important silk producers after China and together with Brazil and Thailand.

Terms of silk nomenclature and manufacture

Natural silk is understood to include both mulberry silk and wild silk (non-mulberry silks). The different forms of cocoon production and their further processing are as follows [3]:

- The main product raw silk, reel silk or grège. This is the part of the cocoon thread that can be reeled in one piece and is about 500 to 1000 meters long. This consists of two elements: fibrinoin, the actual silk, and sericin, the silk bast that acts like a glue, gluing two bavels of fibrinoin together and surrounding them with a protective sheath. As a rule, six to eight cocoons are unreeled at the same time (in parallel) and combined into a single thread and wound onto skeins, which are then further processed as raw silk or grège into yarns or twists. Sericin, which was identified by Fuchs in 1955 as the main allergen of asthma in silk weavers [4], provides perfect protection against the mechanical friction that is unavoidable in further production during winding, warping, weaving and knitting, and is therefore removed by boiling only at the end of production. The main product should therefore be allergen-free.

- By-products of silk production are referred to as silk waste. Flock silk (from the mulberry moth Bombyx mori) is the name given to the outer, irregularly spun scaffold threads, also called pupa bed. The flock silk contains a significantly higher than average proportion of sericin, which is not completely removed during boiling in a mass that also contains other silk waste.

Of the reelable cocoons, the beginning and end of the cocoon thread yields most of the silk waste. They still contain the chrysalides (pupae), the sericin and a small amount of foreign fibers and other impurities. The chrysalides are largely removed by mechanical cleaning, the sericin and other impurities by boiling with soap and other chemical aids or by putrefaction or fermentation. The non-hashable or pierced cocoons are the cocoon envelopes left by the hatching butterfly. They are also cleaned and boiled.

- The products of combing, the first processing operation of the three silk wastes described above are the combs and the combs. After several operations (opening, combing and stretching) the long threads, the tops, are obtained. High-quality, fine schappe yarns are spun from it. They contain practically no more impurities, but still around 3% sericin to reduce electrostatic charging during further processing. The remaining short fibers, the combers, are used to make bourette yarns, and the shortest enter the woollen spinning mills as silk naps as an admixture for fancy and decorative yarns.

These processing products are largely the same for farmed and wild silk, thus necessitating one or another type of identifying, complementary designation, e.g. sheared wild silk yarns.

Mulberry and wild silk differ in sericin content and thickness of fibrin fiber. In the case of wild silk, this has the larger fiber cross-section, which leads to better structural elasticity. Therefore, the wild silk waste is preferred for filling blankets, comforters and mattress pads (fleece).

The “wild silk story” continued – a sheepskin jacket from Scotland also contained wild silk from China!

After the first publication in 1982 [1], it seemed that the silk industry had the problem of allergenic silk waste under control, because only rarely new cases came to observation in the following two years. However, 15 new cases were diagnosed in the allergy ward in 1984 and 16 more in the first half of 1985, so that a 1985 publication reported 118 patients with wild silk allergy and further progress in its control [3]. In another publication in 1993, the number of diagnosed cases even increased to 167, so that attention was again drawn to this problem [5].

Apparently, many of these allergenic blankets – although now withdrawn from the market – were still in use, and in some cases they were passed on to other people by those who had fallen ill. However, even newly available products were not completely allergen-free despite better cleaning and debasing [3].

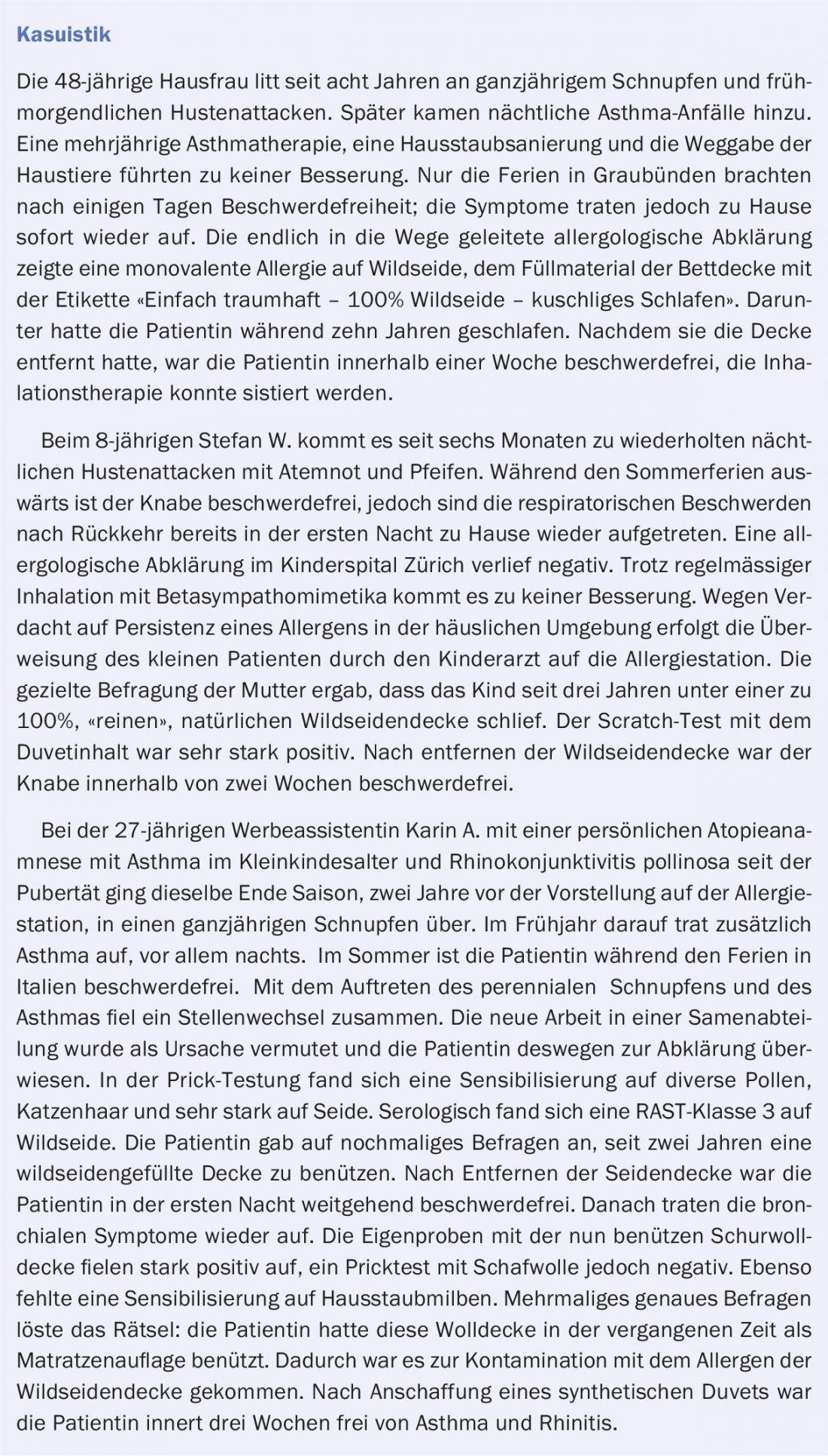

In 1999, the allergy ward saw a 27-year-old female patient who had been diagnosed with wild silk allergy in previous years and was asthma-free after the blanket was discarded. She had bought a supposed sheepskin jacket during her vacations in Ireland [6]. During the train journey from Cork to Limerick she suffered from asthmatic symptoms and likewise when she was back home, especially during the day and in increasing intensity. The allergological clarification confirmed the previously diagnosed strong wild silk allergy (prick test to wild silk extract ++++, CAP-FEIA strongly positive to wild silk with 17.7 kU/l, slightly positive to silk with 3.7 kU/l). Focused questioning revealed that the patient had purchased a cardigan (cardigan) on the occasion of an outing in Cork, which held sheep’s wool. It became her favorite jacket, which she always wore, even at home. Gradually, the asthmatic complaints increased. Inspection of the label (Fig. 8) revealed that the cardigan was “made in China” and was made of 20% silk and 80% cotton. A skin test with cardigan fibers lightly wetted in water was very strongly positive. After giving away the cardigan, the symptoms disappeared completely.

Unusual manifestation and triggering of silk allergy

Authors from London describe a 23-year-old female patient with multiple atopic manifestations and polyvalent sensitization who developed anaphylaxis with generalized urticaria, dyspnea, weakness, and drowsiness after shopping and trying on a silk blouse and dress, which was treated on the spot with intramuscular epinephrine by the paramedics who were called [7]. She had eaten a snack containing sunflower seeds two hours earlier and she suspected these seeds to be allergenic. A few months later, generalized urticaria reappeared while wearing a silk dress at home.

The allergological investigations confirmed the polyvalent sensitization, including to sunflower seeds, by skin tests and serology. However, an oral provocation test with the same was negative. A prick test with the moistened silk fabric of the blouse was strongly positive (wheal 22 mm in diameter), and a CAP IgE test on silk was slightly positive at 1.0 kU/L but negative with wild silk. After application of a piece of wetted silk to the forearm, a wheal appeared after 15 minutes, spreading several centimeters over the contact area. Thus, these tests confirmed an immediate-type contact allergy to silk. Since the double strands of fibroin are still held together by the sericin, the authors assume that the water-soluble allergenic protein is released by wetting the silk piece or by sweating when wearing the dress. Meanwhile, a major allergen of Bombyx mori, an arginine kinase of molecular weight of 42 000, has been identified as Bomb b 1 [8].

In Asian cuisine, the pupa of Bombyx mori is considered a delicacy because of its high protein content. A French tourist with a history of allergic rhinitis suffered anaphylactic shock in China after eating chrysalides fried in oil [9]. The Chinese authors were able to describe 13 cases of allergic reactions after consumption of mulberry dolls and mention that there are more than 1000 cases of allergic reactions annually in China; 50 could be recorded because of treatment in emergency departments.

Comment

The above impressively demonstrates the following:

Wild silk waste, contaminated with sericin that has not been boiled and degummed, and with other protein allergens from moths, caterpillars, and pupae, are aggressive allergens and can sensitize non-atopic individuals, including children. Furthermore, it became clear that testing with self-dust samples is often the only possibility to elicit a rare allergen in addition to a subtle anamnesis. The last case in the casuistry further demonstrates that occasionally elimination of the ceiling alone was not sufficient, but extended remediation was necessary to achieve freedom from symptoms. For example, the bedroom curtains of another patient were contaminated with wild silk allergens and only boiling them led to freedom from symptoms.

Wearing silk underwear, especially if you sweat underneath, can cause allergic reactions even with mulberry silk.

An unusual trigger of a severe silk protein allergy, which can also occur in atopically predisposed tourists when traveling in Asian regions and eating local specialties, is the consumption of mulberry dolls, which are considered a delicacy.

As a new study shows, sericin asthma is still a major problem among workers in the silk industry: out of 120 workers in the silk industry in a city in southern India, 35.83% were sensitized to silk allergen, whereas only 11.11% of a control group, which was not involved in silk production but lived in the same region [10] were not sensitized.

Literature:

- Häcki M, et al: an aggressive inhalation allergen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1982; 107: 166-9.

- Johansson SG, et al: Nightly asthma caused by allergens in silk-filled bed quilts: clinical and immunologic studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985; 75(4): 452-9.

- Wüthrich B, et al: The so-called “wild silk” asthma – a still current inhalation allergy. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1985; 115: 1387-93.

- Fuchs E: Silk as an allergen. Studies on the pathogenesis of asthma in silk weavers. Dtsch. Med. Weeklies 1955; 80: 36-9.

- Eng P, et al: “Wild silk” – another allergen in the bedroom Schweiz Rundschau Med (PRAXIS) 1994; 83: 402-6.

- Borelli S, et al: A silk cardigan inducing asthma. Allergy 1999; 54: 900-1.

- Makatsori M, et al: Silk contact anaphylaxis. Contact Dermatitis 2014; 71: 314-5.

- Liu Z., et al: Identification and characterization of an arginine kinase As a major allergen from silk worm (Bombyx mori) larvae. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2009; 150: 8-14.

- Ji KM, et al: Anaphylactic shock caused by silkworm pupa cionsumption in China. Allergy 2008; 63: 1407-8.

- Gowda G, et al: Sensitization to silk allergen among workers of silk filatures in India: a comparative study. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016; 6(2): 90-3. MCID: PMC4850340.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(6): 46-50

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018 Special Edition (Anniversary Issue), Prof. Brunello Wüthrich