This generic term covers molecular genetically extremely heterogeneous and predominantly hereditary metabolic diseases of heme biosynthesis, which are diagnosed and differentiated by specific biochemical patterns of porphyrins and porphyrin precursors in urine, stool and blood. There is a wide range of different symptoms, although the vast majority of gene carriers remain symptom-free.

All porphyrias are caused by a hereditary metabolic disorder of heme biosynthesis in the liver or erythrocytes. There is an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. The formation of heme from glycine and succinyl-CoA takes place in 8 enzymatic steps, each of which can be affected by a genetic defect. Accordingly, there is an accumulation of porphyrins or their precursors and increased excretion [1,2]. Although only 20-30% of defect carriers become symptomatic (typically between the ages of 20 and 40), there are also massive and life-threatening forms, particularly in acute intermittent porphyria, where attacks are characterized by a triad of abdominal pain, cardiological and neuropsychiatric symptoms [1–3].

Classification

In ICD-10, a distinction is made between erythropoietic porphyrias (main site of formation in the bone marrow) and other forms of porphyria according to the main site of formation of the intermediate products of heme synthesis [4–6]:

- E80.0: Hereditary erythropoietic porphyria (incl. congenital erythropoietic porphyria and erythropoietic porphyria)

- E80.1: Porphyria cutanea tarda

- E80.2: Other porphyria (incl. acute hepatic porphyria and acute intermittent porphyria)

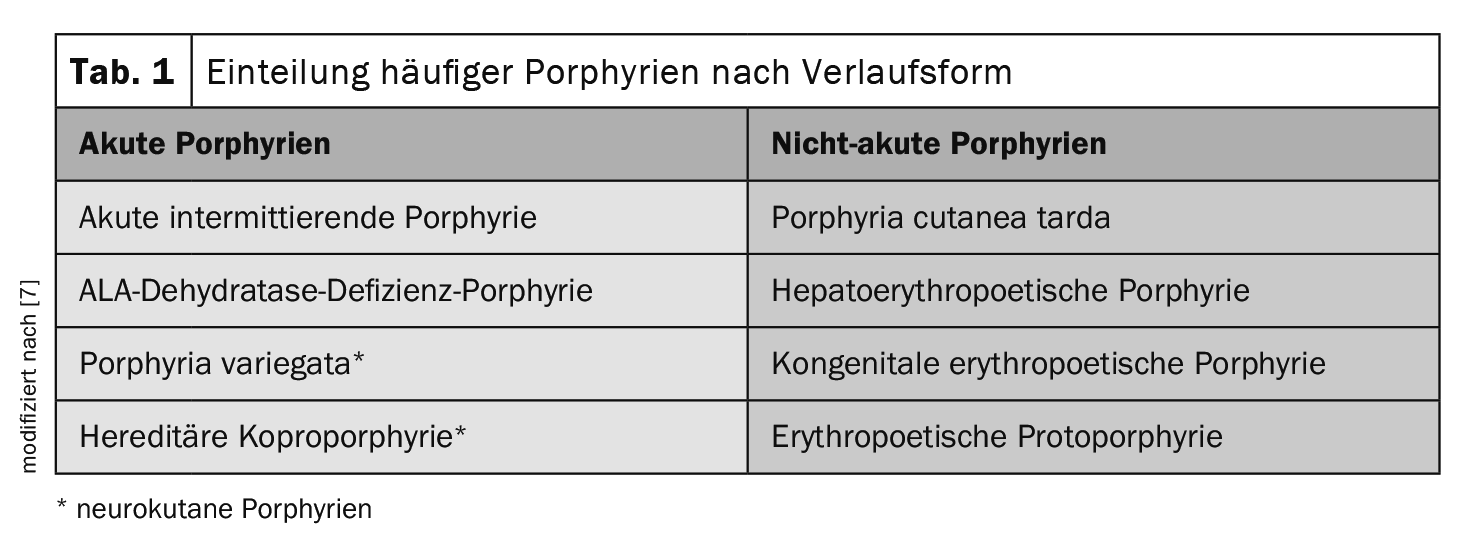

Another criterion for classification is the form of progression (Table 1) . This is the most common in everyday medical practice, as it takes into account potentially life-threatening acute neurovisceral attacks [7]:

In acute porphyrias, acute abdominal pain occurs in episodes together with neurological deficits (so-called neuro-visceral form). Reddish urine is typical during acute attacks. The most common acute porphyria is acute intermittent porphyria (AIP).

In the case of non-acute porphyrias, involvement of the skin is in the foreground. The intermediate products that accumulate in the skin make the skin more sensitive to light, resulting in typical changes such as the formation of blisters and later scars.

Clinic

Porphyria should be considered in case of abdominal symptoms, e.g. colic-like nature, intestinal motility disorders (vomiting, constipation, also diarrhea) in connection with adynamia, confusion, headache, hyponatremia, impaired consciousness, seizures and a severe, rapidly progressive motor-accentuated polyneuropathy [2]. The latter is characterized by a severe, rapid, sometimes painful course with motor and proximal emphasis, sometimes accompanied by cranial nerve neuritis and autonomic disorders. A variety of medications are considered to trigger attacks [2].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of porphyria is based on the detection of accumulated heme precursors in stool, urine and plasma corresponding to the enzyme defect [1]. A qualitative screening detection of porphobilinogen is possible using the Hoesch-Schwartz-Watson test [2]. The clinical suspicion of porphyria must be confirmed by means of metabolite tests in urine, stool and blood by detecting the excessively elevated porphyrin precursors δ-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen as well as porphyrins in the urine. The differential diagnosis of the various forms of porphyria is carried out in a second step in urine, stool and blood samples. In contrast to acute porphyrias, the two porphyrin precursors are not elevated in non-acute porphyrias. Enzyme determinations and molecular genetic examinations are possible to determine the stage of the enzyme defect, but are not relevant for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

| Case study In a 28-year-old woman suffering from cycle-dependent abdominal pain, extensive diagnostics did not reveal any conclusive findings. Psychosomatic treatment was then recommended. However, the symptoms worsened after a fasting cure: painful paraesthesia in the thighs, nausea, constipation and vomiting occurred. Metamizole was prescribed to alleviate the symptoms. |

| In the course of the disease, the patient developed incipient paralysis of the extensor muscles of both hands, severe hyponatremia (sodium concentration 105 mmol/l) and hallucinations. This led to hospitalization and immediate intensive care. After reddish urine was found in the urine bag and massively increased ALA and PBG concentrations** were found in a urine sample, the diagnosis of acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) was made. Acute hepatic porphyrias are characterized by the occurrence of neuro-visceral attacks with or without cutaneous manifestations. The most common AHP is acute intermittent porphyria. |

| The patient was then treated with hemarginate i.v. (3 mg/kgKG in 100 ml 20% albumin solution over 30 min) for four days. Due to the vomiting, caloric intake had to be administered parenterally via infusions. In the acute phase, the target calorie intake was 24 kcal/kg bw per day. With regard to individual metabolic tolerance, daily serum phosphate determinations and six-hourly blood glucose checks were carried out to prevent refeeding syndrome. |

| ** ALA=delta-aminolevulinic acid, PBG=porphobilinogen |

| to [8,9] |

Therapy

Initially, all porphyrinogenic drugs should be discontinued and replaced with “porphyria-compatible” drugs [2]. The following measures are also recommended:

Acute porphyrias: In severe attacks and with a confirmed diagnosis, treatment with hemarginate is carried out [6]. In addition, sufficient glucose (4-5 g/kg bw/d) should be administered. Depending on the patient’s condition, this can be given orally, by nasogastric tube or intravenously. Oral glucose administration can be carried out with e.g. maltodextrin solution (25%). Even with asymptomatic courses of acute intermittent porphyria, regular examinations (1-2 times a year) should be carried out in a liver center, as this form, as well as porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), carries an increased risk of developing a liver tumor. For porphyria variegata and hereditary coproporphyria, adequate photoprotection and prophylaxis of acute relapses are among the most important measures [6].

Non-acute porphyrias: In non-acute porphyrias, the cutaneous symptoms are in the foreground [6]. As a general rule, patients should avoid direct exposure of the skin to UV light. In PCT, excessive iron storage can be reduced by phlebotomy, which usually leads to an improvement in symptoms. Another therapeutic approach is the administration of the antimalarial drug chloroquine [6]. In the treatment of erythropoietic protoporphyria, an effective reduction in photosensitivity can be achieved by taking beta-carotene daily from February to October.

Literature:

- Layer P, Rosien U (eds.). Liver. Practical gastroenterology. 2011:281-366.

- Straube A, et al: Metabolic disorders. NeuroIntensiv 2015 Apr 30: 643-723.

- Kauppinen R: Porphyrias. Lancet 2005; 365: 241-252.

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: ICD-10, www.icd-code.de, (last accessed 09.11.2023)

- Flexikon, https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Porphyrie,(last accessed 09.11.2023)

- Düsseldorf University Hospital, www.uniklinik-

duesseldorf.de/patienten-besucher/klinikeninstitutezentren/klinik-fuer-gastroenterologie-hepatologie-und-infektiologie/klinik/fuer-patienten/behandlungsschwerpunkte/metabolic-diseases/porphyria, (last accessed 09.11.2023) - Muschalek W, et al: The porphyrias. JDDG 2022; (20, Issue 3): 316-333.

- Stölzel U, Stauch T, Kubisch I. Porphyrias [Porphyria]. Internist (Berl) 2021; 62(9): 937-951.

- orphanet: Porphyria, acute hepatic, www.orpha.net,(last accessed 09.11.2023).

GP PRACTICE 2023: 18(11): 48-49