Irritable bowel patients suffer from intolerance reactions to food. A low-FODMAP diet or a gluten-free diet can significantly alleviate these symptoms.

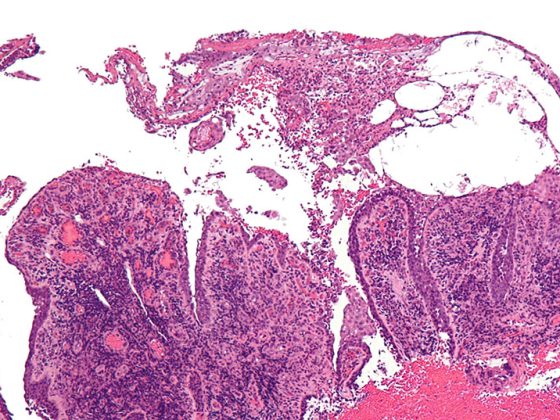

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have impaired intestinal barrier, motility, secretion, and/or visceral sensitivity. Often, IBS is associated with impaired enteric immune balance, with microinflammatory or neuroimmunological processes in the intestinal mucosa leading to local proliferation of immune cells and/or EC cells [1].

“It is now well established that irritable bowel syndrome patients are not simply imagining things,” says Prof. Dr. med. Yurdagül Zopf, Division Head of Nutritional Medicine at the University Hospital Erlangen (D), “but that inflammatory processes take place in IBS that are not found in healthy controls.” It is known from histological studies that IBS patients have increased levels of intraepithelial lymphocytes, mast cells, and EC cells. Mucosal biopsies also showed increased density of nerve fibers [2–4]. In addition, IBS patients had significantly elevated levels of serotonin, histamine, and tryptase when mediator concentration was measured [5]. This altered mucosal mediator profile activates the enteric nervous system and primary afferent (nociceptive) nerves [1].

The diagnosis is made by exclusion procedure. Diagnostic tools include pathogen testing in stool (microbial and virologic diagnostics with focus on inflammation-related shifts; worm eggs), ileocolonoscopy with step biopsies, esophagogastroduodenoscopy with duodenal biopsies, and lactose, fructose, and sorbitol H2 breath tests. Advanced laboratory diagnostics include serum electrolytes, renal retention values, liver and pancreatic enzymes, TSH, blood glucose/HbA1c, celiac antibodies (transglutaminase-AK), and fecal calprotectin A.

Regulation through nutrition

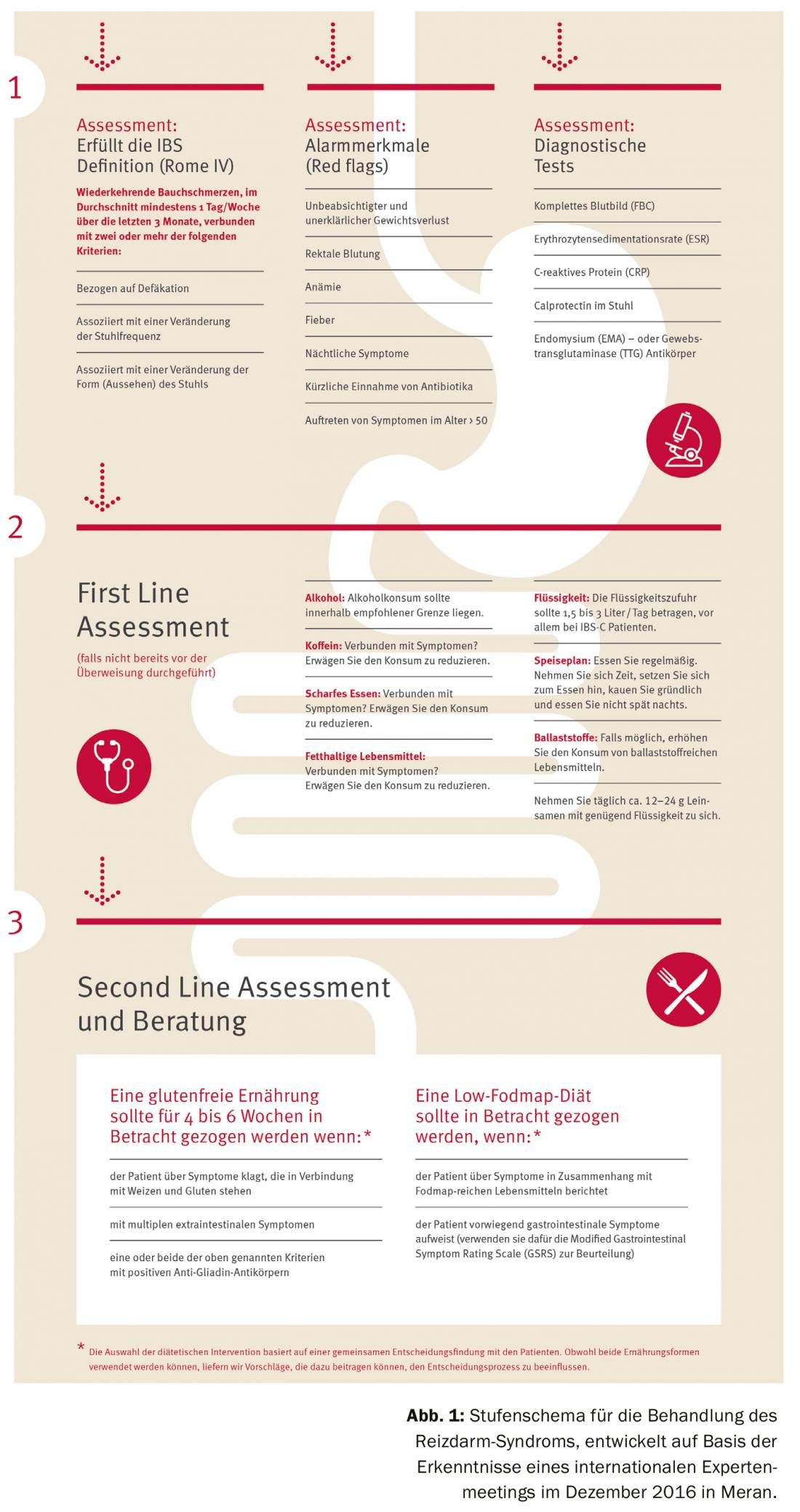

The etiopathogenesis of IBS is complex and varies from individual to individual. Accordingly, many therapeutic approaches exist that are predominantly oriented to the treatment of the leading symptom. These include pharmacological measures (e.g., laxatives, spasmolytics, antidepressants, loperamide), phytotherapy, psychohygiene and exercise, and diet [6].

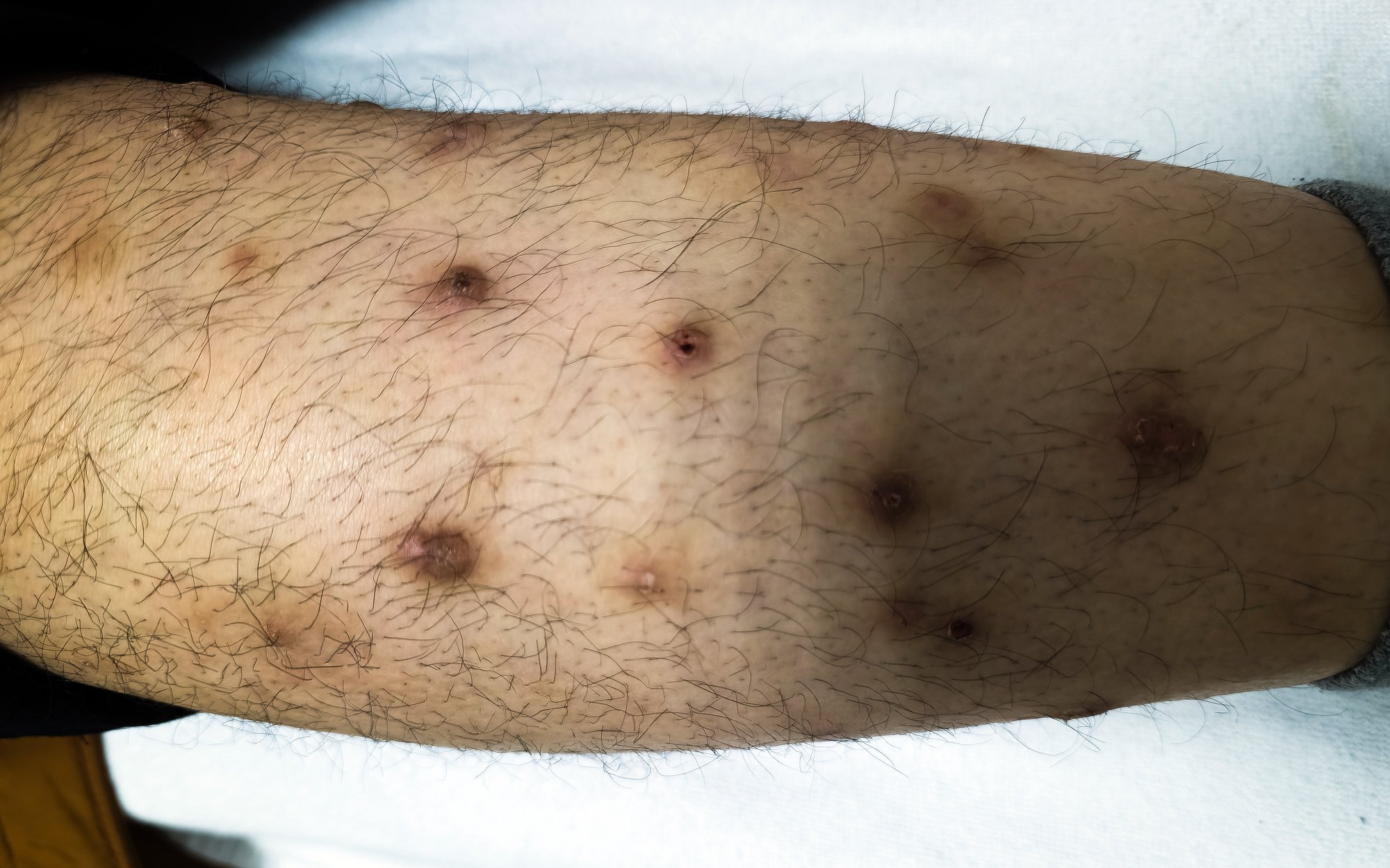

Nutrition in particular plays an important role in the regulation of IBS (Fig. 1). Various studies have shown that IBS patients react to different foods. Women tend to suffer from intolerance reactions more frequently than men, which may be explained by the higher mast cell density in women. However, intolerance reactions occur regardless of gender, IBS type, anxiety that may be present, or location of treatment (hospital vs. outpatient) [7].

The tolerability of dietary fiber has been well studied. In this case, it is essential to consume soluble dietary fiber instead of insoluble fiber, as the latter can even aggravate the symptoms: Hemicellulose, for example (contained in wheat and rye), results in increased gas production. “The patient has more severe symptoms than before and is even incomplient to further dietary modulations in the course,” warns Prof. Zopf.

It is also confirmed that allergies and intolerances are higher in prevalence in IBS patients [8]. Although only IgE-induced allergies can be detected diagnostically, patients with increased tryptase, histamine and mast cell activity in the gut are at higher risk for immunological reactions.

Gluten-free diet also helps IBS patients

One protein in particular is often the focus of interest: gluten. Here it is important to differentiate who actually cannot tolerate gluten – because a low gluten diet is not automatically healthier for everyone.

A lifelong gluten-free diet is the foundation of celiac disease treatment. Patients with gluten/wheat intolerance also benefit from such an adapted diet, whereas it is not recommended for healthy individuals, since according to current studies there is no clinical benefit for healthy individuals.

In many IBS patients, symptoms are triggered or exacerbated by wheat or gluten. In these cases, a gluten-free diet leads to significant improvement in symptoms, according to the IBS (GIBS) study published in 2017. There, symptoms improved in 34% of IBS patients in a statistically significant and clinically relevant manner in the course of a four-month gluten-free diet. Adherence to the dietary change remained in many subjects even after the study: A very high proportion (all responders, 55% of non-responders) continued to follow a gluten-free diet [9].

FODMAP – observe individual tolerance level!

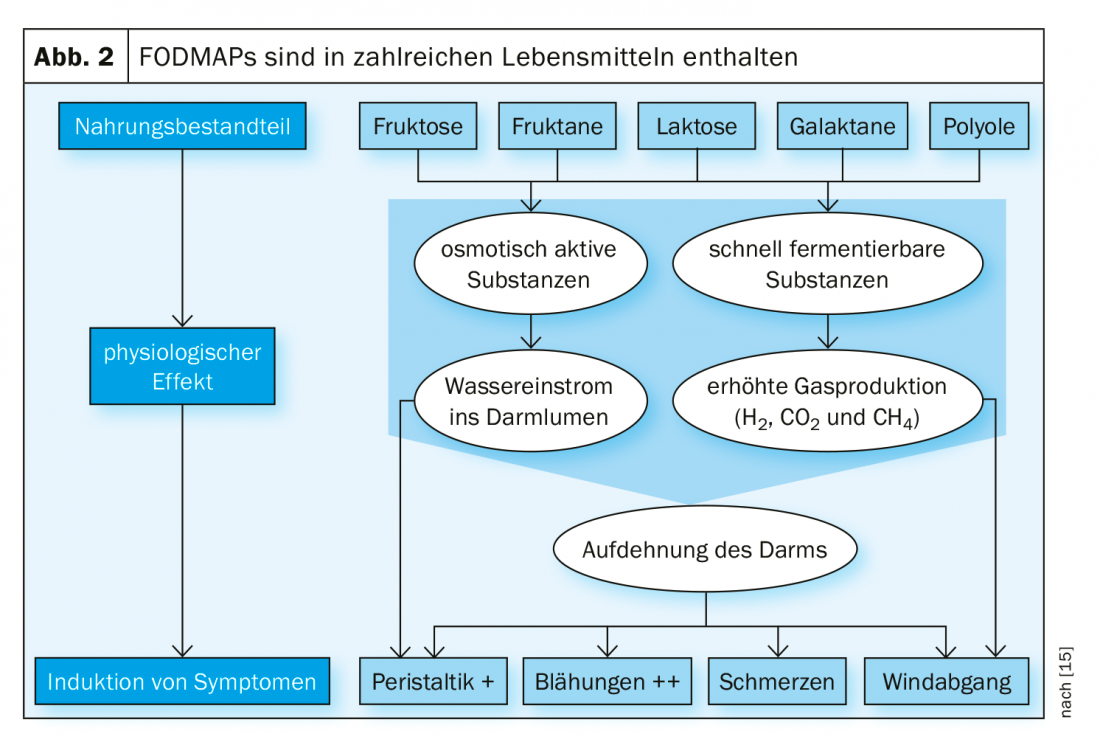

FODMAPs – fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides as well as polyols – are hardly if at all absorbed in the small intestine. Osmotic processes and fermentation result in increased water influx and increased gas formation. Malabsorption of these carbohydrates is normal, and many people do not feel any negative effects when consuming FODMAPs. IBS patients, on the other hand, sometimes experience severe symptoms in response to FODMAPs, such as bloating, pain and discomfort, flatulence, change in stool, and/or lethargy (Fig. 2). They respond with significantly higher gas production than healthy controls [10]. A low-FODMAP diet leads to improvement of symptoms in 68-76% of patients [11].

Prof. Zopf emphasizes the importance of an individually adapted approach: “Each of us has a different tolerance level of FODMAP. FODMAP diet does not mean: reduction to zero. The threshold that is tolerable for the individual must be detected”. Thus, a low-FODMAP diet does not always have to be followed in its maximum form. It can be enough to reduce even just shares.

In any case, to avoid malnutrition, it is important that the diet is carried out in the company of a professional nutrition therapist. This guides the patient through three stages:

- Elimination diet

- Re-introduce (to check which substances are causing problems).

- Adaptation

One concern associated with the low-FODMAP diet is the associated reduction in bifidobacteria [12]. Such a change in intestinal flora is understandable, especially since FODMAPs produce various substances that maintain mucosal integrity. However, a later study showed that concurrent probiotic therapy can stabilize the bifidobacteria population [13].

Dietary changes also show positive effects in relation to serotonin and PYY levels altered in IBS patients [14].

Source: Zopf Y: “Influence of diet on IBS”. Lecture in the context of the satellite symposium Dr. Schär “Nutrition in irritable bowel syndrome”, DGIM 2019, Wiesbaden (D).

Literature:

- Layer P, et al: S3 Guideline Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Definition, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Therapy. Joint guideline of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and the German Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (DGNM). Z Gastroenterol 2011; 49(2): 237-293.

- Akbar A, et al: Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1-expressing sensory fibers in irritable bowel syndrome and their correlation with abdominal pain. Gut 2008; 57(7): 923-929.

- Guilarte M, et al: Diarrhea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut 2007; 56(2): 203-209.

- Spiller RC: Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2003; 124(6): 1662-1671.

- Buhner S, et al: Activation of human enteric neurons by supernatants of colonic biopsy speci-mens from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009; 137(4): 1425-1434.

- Schaub N, Schaub N: Irritable bowel syndrome. Insights and Outlook 2012. SMF 2012; 12(25): 505-513.

- Simrén M: Altering the Gastrointestinal Flora in Patients with Functional Bowel Disorders: A Way Ahead? Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2009; 2(4 Suppl): 5-8.

- Boettcher E, Crowe SE: Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastro-enterol 2013; 108(5): 728-736.

- Barmeyer C, et al: Long-term response to gluten-free diet as evidence for non-celiac wheat sensitivity in one third of patients with diarrhea-dominant and mixed-type irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; 32(1): 29-39.

- Ong DK, et al: Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(8): 1366-1373.

- Tuck CJ, et al: Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols: role in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 8(7): 819-834.

- Staudacher HM, et al: Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction Reduces Luminal Bifidobacteria and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Nutrition Disease 2012; 142(8): 1510-1518.

- Staudacher HM, et al: A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and A Probiotic Restores Bifidobacterium Species: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology 2017; 153(4): 936-947.

- Mazzawi T, El-Salhy M: Effect of diet and individual dietary guidance on gastrointestinal endocrine cells in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med 2017; 40(4): 943-952.

- Beatrice Schilling: FODMAP concept. https://fodmap.ch/de/fodmap-konzept, last accessed 08/13/2019.

- Leiß O: Fiber, Food Intolerances, FODMAPs, Gluten and Functional Bowel Disease – Update 2014. Z Gastroenterol 2014; 52(11): 1277-1298.

GP PRACTICE 2019; 14(8): 40-41