The concept of artificial intelligence dates back to the 1950s. 20th century and includes a collection of technologies that allow a computer to emulate typical characteristics of human intelligence. Initially, great hopes were placed in these technologies and early attempts were made to establish them in medicine. At the beginning of the In the 21st century, research into AI in medicine was rather quiet due to the initial sobering results. However, several important developments paved the way for the technology’s breakthrough.

The term artificial intelligence originated in the 1950s and encompasses a collection of technologies that allow a computer to emulate typical characteristics of human intelligence [1]. Initially, great hopes were placed in these technologies and early attempts were made to establish them in medicine. Examples from the 1970s include programs for bacterial identification in infectious diseases [2] or for coronary heart disease prognosis [3]. A certain disillusionment occurred in the 1990s: an editorial [4] in the famous journal New England Journal of Medicine gave the programs for computer-aided diagnosis available at that time a grade of “C”, which roughly corresponds to a “3” in the Swiss grading system. These programs produced a false diagnosis 30 to 50 percent of the time, making their use and acceptance in the clinic difficult. At the beginning of the 21st century, research into artificial intelligence in medicine was rather quiet due to the initially sobering results. However, several important developments paved the way for the technology’s breakthrough.

Deep Learning

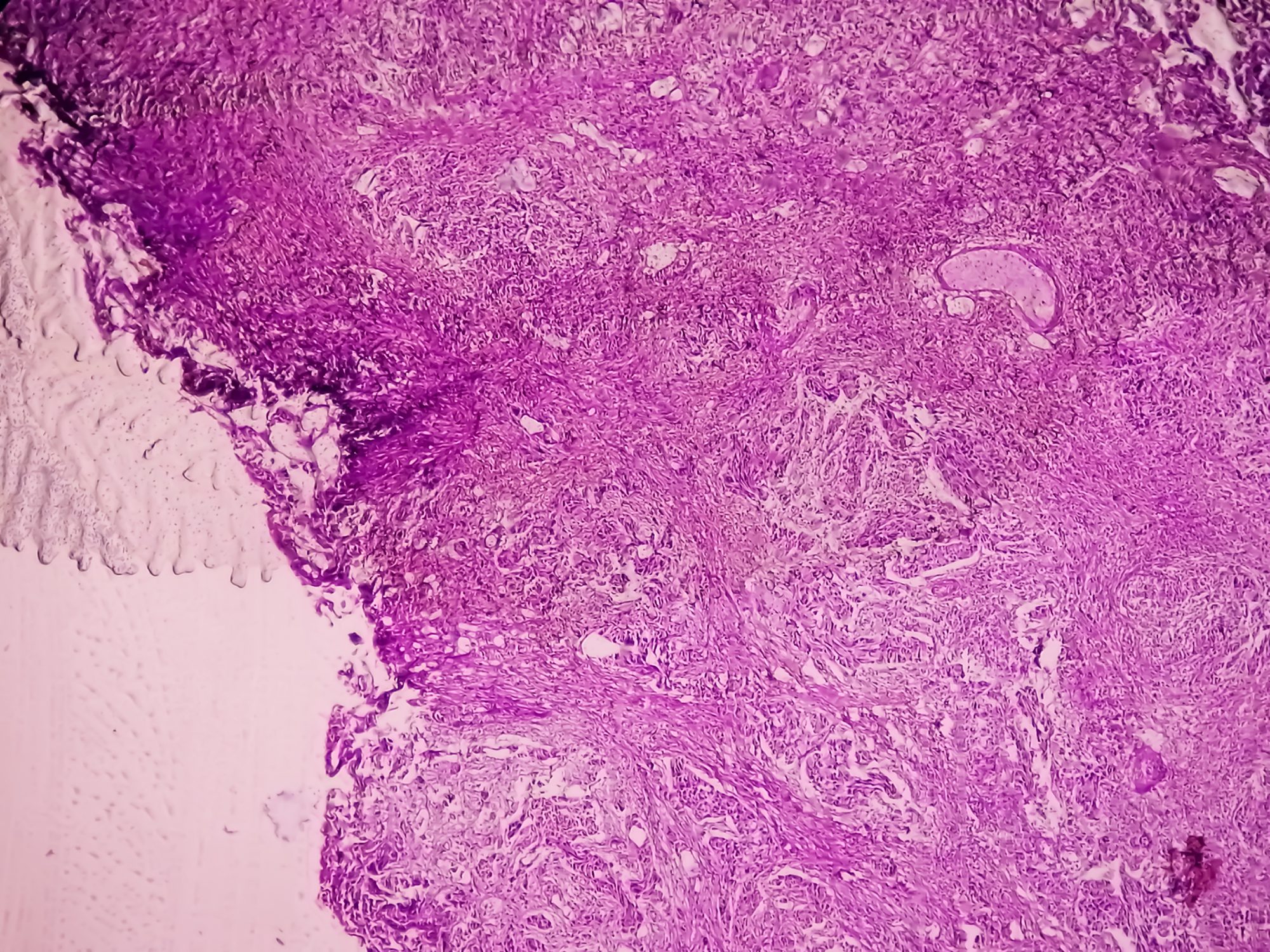

On the one hand, there has been a steady expansion in the use of electronic medical records. Computers thus gained access to large medical data sets. The large amount of data enabled the creation and further development of a new generation of artificial intelligence programs. These programs were developed in the 2010s and are now grouped under the term deep learning . This is understood to be algorithms based on artificial neural networks that can recognize patterns in large amounts of data with high precision. Remarkably – and with great importance for medicine – these programs have an outstanding ability to recognize structures in images [5]. In direct comparison with human viewers, computers have been shown to perform far better in recognizing patterns in images and to be below the human error rate of 5% [6]. A research group at Stanford University in California applied Deep Learning technology to the field of dermatology in 2017. In a seminal paper, it was shown that computers are on par with dermatologists in the detection of malignant skin lesions [6]. Since this publication, more and more new studies have reported similar results in various diagnostic disciplines (for example in pathology or radiology [7–10]). In parallel with image recognition – and with equally far-reaching significance for medicine – deep learning technologyhas also led to breakthroughs in speech recognition in recent years [11]. As a result, computers can increasingly understand and analyze medical data written in natural language (discharge reports, diagnostic reports, etc.) or even compose texts themselves [12]. In summary, the following can be said: Thanks to electronic medical records, computers have broader access to medical data that is still mainly in unstructured form (images or text). A technology (Deep Learning) can effectively process this unstructured data, enabling it to increasingly emulate medical activities (diagnosis, treatment decision or writing an exit report).

To what extent and in what time frame these new technologies will influence medicine remains an open question. In the coming section, we will explore these questions and pay particular attention to the opportunities and risks of artificial intelligence in everyday medical practice (Tab. 1).

Use of AI in everyday clinical practice: competition for the medical practitioner?

Currently, there is a growing interest in using artificial intelligence (AI) to complement, enhance, or even replace the diagnostic intelligence of the physician. Proponents of AI expect that such technologies could improve diagnostic accuracy (with less under- and overdiagnosis) in addition to diagnostic efficiency[13].

However, others have argued that this will create another information burden during an already overloaded office hour. It could do very little to improve patient outcomes, physician stress levels or the financial state of the healthcare system. These arguments are sometimes based on experience with existing systems that assist physicians in activities such as drug interaction detection, often failing to convince because of false alarms or non-relevant interventions[14].

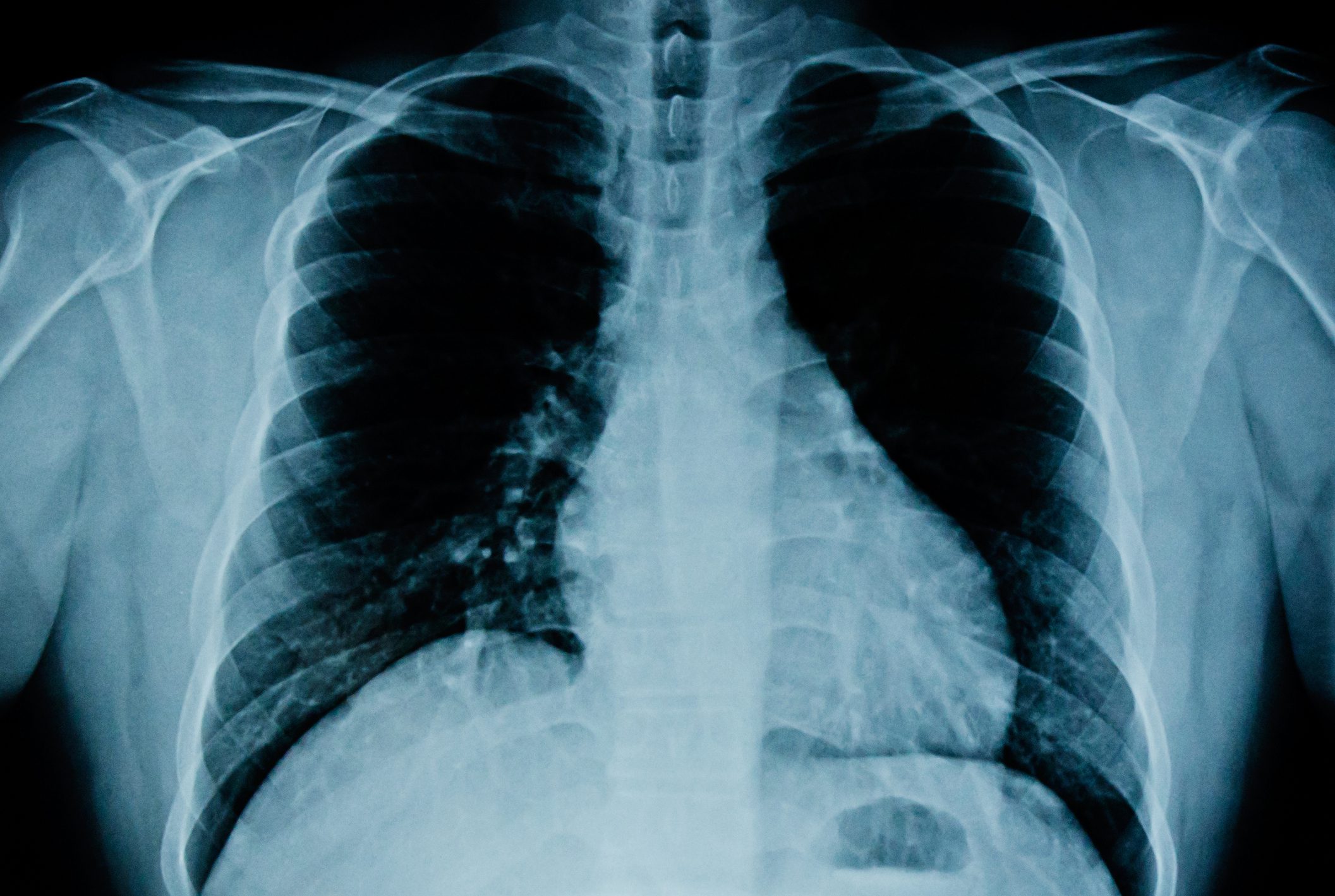

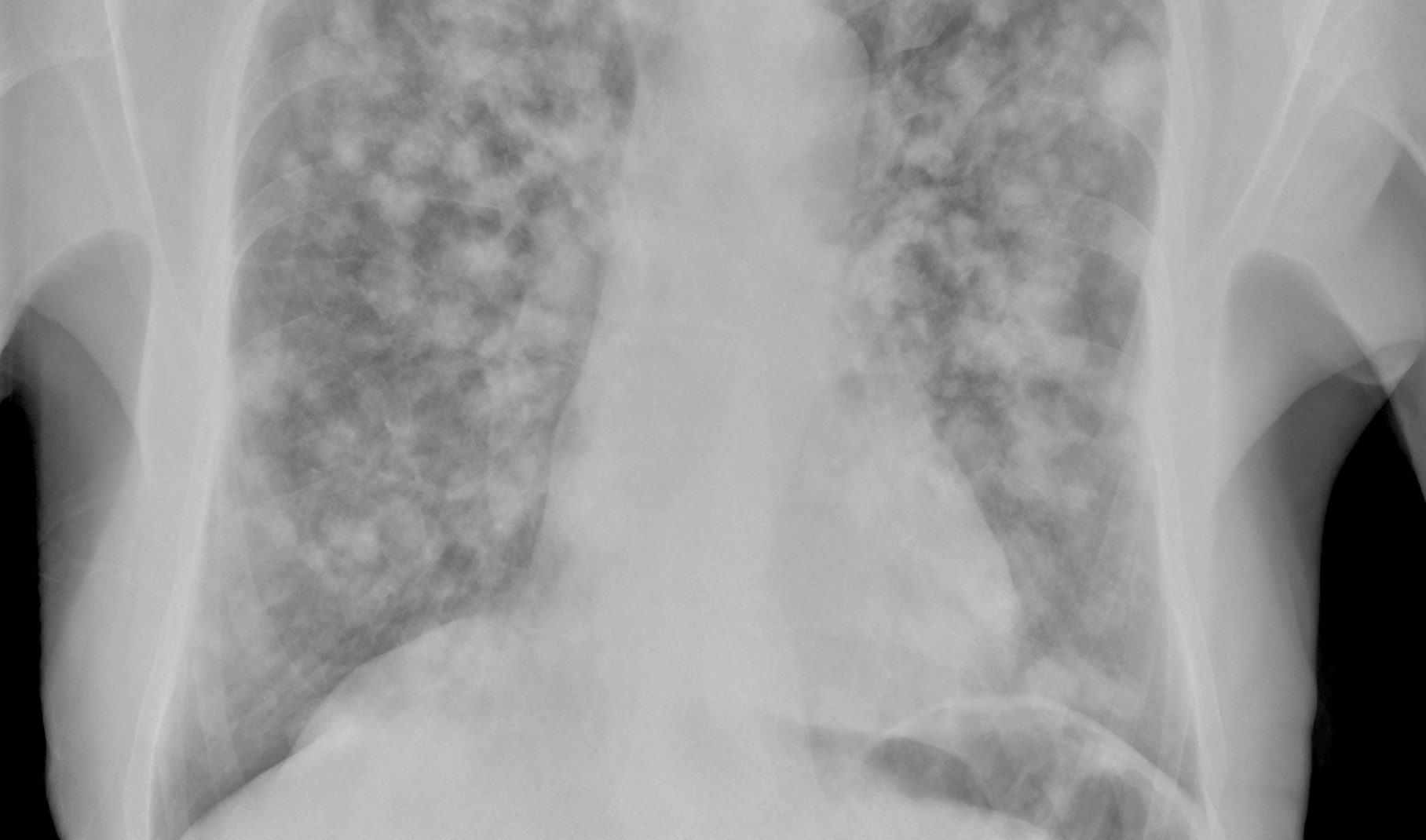

However, with a new generation of AI systems, it can be expected that they will become established in everyday clinical practice in the longer term. The reason lies mainly in the capacity of these systems to study an unlimited number of cases and thus perfect a diagnostic algorithm. A radiologist, for example, has access to a large but then limited number of radiological images during his training and also professional activity, which he can use to sharpen his diagnostic skills. In contrast, computers have access to potentially all radiological images ever acquired at one or more hospitals. Accordingly, the computer can rely on radiological images and findings from hundreds of radiologists and can thus effectively emulate, albeit indirectly, their collective knowledge. Thus, a single radiologist is at a disadvantage compared to a computer.

These new generations of AI systems do not necessarily have to operate autonomously (without physician supervision), as they are already being used, for example, in ophthalmology to diagnose diabetic retinopathy [9]. Rather, AI will support physician activities, such as radiology AI systems that prioritize radiology images yet to be adjudicated by severity in the background, or AI-based assistance systems that alert radiologists to a fracture in the radiograph and have been shown to increase diagnostic precision [17]. Whether specialists will actually accept and use this AI help is still an open question at this point. In any case, non-specialists, primary care physicians, physicians-in-training, and other medical personnel will be empowered by AI to perform complex diagnostic tests themselves.

It should be noted here, however, that an AI system can never fully replace the physician, as the system lacks empathy and compassion for the patient for the time being. A physician must understand the patient’s context and absorb social as well as psychological circumstances with empathy, care, and compassion. Explicit knowledge about the predictive value of symptoms can be taught to an AI system, but that it learns how to gain a person’s trust is unlikely at this point.

Quality improvement of medicine

Properly applied, however, AI systems could bring about an increase in the quality of medical care. The AI systems do not fatigue and guarantee consistent diagnostic performance regardless of time of day or patient volume. The AI can monitor medical processes in the background and take corrective action. Optimistically, AI could lead to significant time savings, improving the quality of the patient-doctor relationship. Specifically, doctors could leave routine examinations to AI and devote more time to talking to patients. An example from GP practice would be advising a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. GPs spend a lot of time collecting information from various sources, for example reading outpatient or inpatient discharge reports, analyzing blood tests from the last few months and looking up clinical guidelines. In contrast, AI assistance systems can automatically prepare the most important information and identify risks and measures based on the patient’s individual risk profile. AI systems can also play an important role in prevention. These systems could proactively suggest consultations when they determine that a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus is at increased risk of developing a particular diabetic complication and warrants intervention.

AI in everyday practice

AI-based systems also bring supportive diagnostic expertise to primary care. An image of a skin lesion is sufficient to diagnose its etiology using an AI system. Images could be captured in a primary care physician’s office and sent to a specialized dermatology AI system for timely analysis [6]. Patients at low risk would receive immediate reassurance, while patients at higher risk for melanoma could be referred to a dermatologist immediately and not have to wait long, as specialists only see selected cases. This concept is not only limited to the field of dermatology, but also in the interpretation of many other complex patient data, for example retinal scans, X-rays or ultrasound images. Many of these images can soon be collected and analyzed with relatively inexpensive equipment and AI. A good example is a new generation of small ultrasound devices that connect directly to smartphones and can use AI to analyze a wide variety of organ systems[18].

Other applications are also relevant. For example, new approaches to drug interaction detection based on deep learning algorithms show potential. Polypharmacy is a growing problem in medicine with a high risk of adverse drug interactions. AI systems that assist physicians can play an important role in detection and also in prevention (Fig. 1). [15,16]

However, one hurdle to the safe and widespread implementation of AI systems in family practice and many other areas of medicine is often inadequate data entry. In healthcare, the process is rarely automated and often depends on physicians who lack the time to enter data. Without accurate and up-to-date data, AI systems do not have the necessary information to generate a working algorithm for proper decision making [19]. A great deal of effort is still needed to improve the data situation accordingly.

Black Box Nature and Systematic Bias of AI

The development of deep-learning algorithmsgives computers the ability to explore increasingly complex associations. Deep learning algorithmsbuild on the idea of a “computerized” brain. However, the neural processes going on in the system are not always comprehensible to humans (AI is a “black box”). This makes the interpretation of the results more difficult. This, in turn, can lead to a reduction in trust toward the system, making integration into clinical practice more difficult [19]. Also, an AI system is only as good as the data provided to it; should the data be flawed or biased, it may contain systematic biases. The risk for a systematic misstatement of the AI system thus becomes greater. For example, patients with low socioeconomic status may receive fewer diagnostic tests and medications for chronic conditions and have limited access to health care. Thus, an AI system has a limited amount of information about this patient population and may suggest a needed intervention later than for patients who visit the physician regularly[20].

On the other hand, physicians are not immune to bias. Clinical decision making often depends in part on a set of “rules of thumb” and algorithms. Sheringham et al. [21] for example, were able to show that British GPs were no more likely to clarify patients with high-risk symptoms of cancer than patients with low-risk symptoms. It has also been shown that patients with the same symptoms are treated or clarified differently [21].

An AI system can potentially objectively synthesize and interpret all the data available in the electronic medical record, which is impossible for the physician due to the vast amount of data. Physician/AI interaction is synergistic and holds the opportunity to mitigate bias and achieve better patient care.

Open Data – Implications for AI, Privacy and Security

Open Data is a trend that is becoming increasingly important in healthcare as well. A major advantage of Open Data is that data from clinical trials and other sources can be used, reanalyzed, shared, and combined with other data. Open Data facilitates scientific collaboration, enriches research, improves analytical capacity to make decisions, and provides for much faster progress in medicine. MIMIC-IV, for example, is a dataset that contains unidentifiable health data on over 60,000 intensive care patients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from 2008 to 2019 and is publicly available [22].

Open Data is spurring AI, which depends on very large patient datasets. This aspect will inevitably lead, at least at the data level, to a convergence of healthcare systems so that sufficient data for AI can be gathered in the network of hospitals. This “data transparency” could lead to other positive effects in the longer term, such as better cost control in healthcare.

The dependence on data also has its downsides. Medical data contains highly sensitive information that must be protected for data protection reasons and, at first glance, represents a major barrier to Open Data. The use of open data therefore requires a careful balance to be struck between free access and patient privacy. To meet these security and privacy challenges, great emphasis must be placed on legal safeguards (“data use agreements”), advanced encryption algorithms, and pseudo-anonymization of personal data. AI systems in general should guarantee privacy and security, as well as establish good governance standards [23].

Conclusion

The use of AI systems in medical practice for more efficient diagnosis confirmation and therapy requires the acceptance and support of physicians. Before use, it is important to ensure that the AI-physician combination will provide a benefit to patient care, including by reducing the burden on physicians and without creating uncertainty for patients. What is therefore needed is AI research that holistically examines and systematically sheds light on the consequences for everyday clinical practice.

Take-Home-Messages

- Artificial intelligence is a growing field that will have a major impact on the medicine of tomorrow.

- A basic understanding of artificial intelligence is critical for proper implementation in clinical practice.

- The support of physician activities by artificial intelligence leads to potential quality improvement and time relief.

- Artificial intelligence is not infallible. Promising new systems are the subject of current research, but have not yet been widely adopted.

clinical application still has implementation difficulties.

Acknowledgement

We thank Lukas Bachmann, MD, for his constructive review of the article.

Literature:

- McCarthy J, Minsky ML, Rochester N, Shannon CE: A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Magazine 1955; 27(4): 12.

- Shortliffe EH, Buchanan BG: A model of inexact reasoning in medicine. Mathematical Biosciences 1975; 23(3): 351–379.

- Rosati RA, McNeer JF, Starmer CF, et al.: A new information system for medical practice. Arch Intern Med 1975; 135(8): 1017–1024.

- Kassirer JP: A report card on computer-assisted diagnosis-the grade: C. N Engl J Med 1994; 330(25): 1824–1825.

- Langlotz CP, Allen B, Erickson BJ, et al.: A Roadmap for Foundational Research on Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging: From the 2018 NIH/RSNA/ACR/The Academy Workshop. Radiology 2019; 291(3): 781–791.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al: Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017; 542(7639): 115-118.

- Kooi T, Litjens G, van Ginneken B, et al: Large scale deep learning for computer aided detection of mammographic lesions. Med Image Anal 2017; 35: 303-312.

- Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al: Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs. JAMA 2016; 316(22): 2402-2410.

- De Fauw J, Ledsam JR, Romera-Paredes B, et al: Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat Med 2018; 24(9): 1342-1350.

- van der Laak J, Litjens G, Ciompi F: Deep learning in histopathology: the path to the clinic. Nat Med 2021; 27(5): 775-784.

- Li Y, Rao S, Solares JRA, et al.: BEHRT: Transformer for Electronic Health Records. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1): 7155.

- Nooralahzadeh F, Gonzalez NP, Frauenfelder T, et al: Progressive Transformer-Based Generation of Radiology Reports. arXiv preprint arXiv:210209777; 2021.

- Summerton N, Cansdale M: Artificial intelligence and diagnosis in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2019; 69(684): 324–325.

- Embi PJ, Leonard AC: Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19(e1): e145-148.

- Schwarz K, Allam A, Gonzalez NAP, Krauthammer M: AttentionDDI: Siamese Attention-based Deep Learning method for drug-drug interaction predictions. ArXiv. 2020; abs/2012.13248.

- Moriarty F, Hardy C, Bennett K, et al: Trends and interaction of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in primary care over 15 years in Ireland: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015; 5(9): e008656.

- Rainey C, McConnell J, Hughes C, et al: Artificial intelligence for diagnosis of fractures on plain radiographs: A scoping review of current literature. Intelligence-Based Medicine 2021; 5: 100033.

- Buonsenso D, Pata D, Chiaretti A: COVID-19 outbreak: less stethoscope, more ultrasound. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8(5): e27.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA: Primary Care Artificial Intelligence: A Branch Hiding in Plain Sight. Ann Fam Med 2020; 18(3): 194-195.

- Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S.: Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019; 366(6464): 447-453.

- Sheringham J, Sequeira R, Myles J, et al.: Variations in GPs’ decisions to investigate suspected lung cancer: a factorial experiment using multimedia vignettes. BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26(6): 449–459.

- Johnson ABL, Pollard T, Horng S, et al: MIMIC-IV (version 1.0). PhysioNet0 2021; doi: 10.13026/s6n6-xd98.

- Kobayashi S, Kane TB, Paton C: The Privacy and Security Implications of Open Data in Healthcare. Yearb Med Inform 2018; 27(1): 41–47.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2023; 11(6): 12–16