Oral chemotherapy is an evidence-based option in drug therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Both the favorable side effect profile and the patient autonomy ensured by the oral form of administration have a favorable effect on quality of life. Patient adherence significantly affects treatability with an oral cytostatic agent and thus influences treatment safety and outcome. Close monitoring with regular physician consultations and the promotion of personal responsibility contribute significantly to improving adherence.

To date, chemotherapy for metastatic breast carcinoma is predominantly administered intravenously. However, oral dosage forms of cytostatic drugs, when used correctly, can be associated with significant benefits for patients, providers, and payers. Patient preference and their ability to implement the prescribed therapy are important factors, as are bioavailability and cost-effectiveness.

Oral cytostatics such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, vinorelbine, and capecitabine have been used for a very long time in the treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma, with capecitabine and vinorelbine predominating in recent years. In the future, the representative selection of convincing data on oral chemotherapy could help oncology physicians to overcome the still widespread reservations against this form of therapy. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the specifics of indication, patient selection, and application.

Disadvantages of intravenous chemotherapy

With 5518 new cases and 1376 deaths per year in Switzerland, breast carcinoma is the most common cancer in women [1]. In the metastatic setting, median overall survival is 20-28 months [2]. Palliative therapy in metastatic breast cancer implies restoration and maintenance of quality of life and reduction of tumor-related symptoms. The prolongation of life that can be achieved by optimized therapy should only be a secondary therapeutic goal.

Despite abundant trial data on the efficacy and practicality of oral cytostatics, prescriptions for intravenous cytostatics predominate. This is due to concerns on the part of treating oncologists regarding adherence, bioavailability, and treatment benefit for patients [3]. In this context, the use of intravenous chemotherapy is associated with considerable additional expense for the patient, the health care provider and the service provider. Patients spend a not insignificant amount of time in medical facilities for cytostatic application due to their commitment to oncology outpatient clinics, which in turn has an impact on quality of life. Physician prescribing of cytostatics for i.v. applications involves administrative time and effort, depending on the medical facility. Furthermore, additional health care system resources must be utilized through the use of nurse practitioners and application sites [4]. Thus, the benefits of oral chemotherapy must be factored into the decision-making process when weighing and selecting chemotherapy. The preparations vinorelbine oral and capecitabine will be examined in more detail below with regard to their properties and mode of application.

Oral vinorelbine

Oral vinorelbine (Navelbine Oral®) is a well-established substance with a firm place in the therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. Vinorelbine belongs to the vinca alkaloids and inhibits mitosis via inhibition of tubulin polimerization. It can be used as a mono-substance, but also in combination with capecitabine or trastuzumab (Herceptin®). Vonorelbine has a response rate of 26% even after pretreatment with anthracyclines and taxanes [5]. The most common side effects of oral vonorelbine are nausea, vomiting, and myelotoxicity. This necessitates the routine use of antiemetic therapy (e.g. HT3 antagonists) and regular monitoring by differential blood count. Nausea can also be prevented by taking the tablets after a small meal.

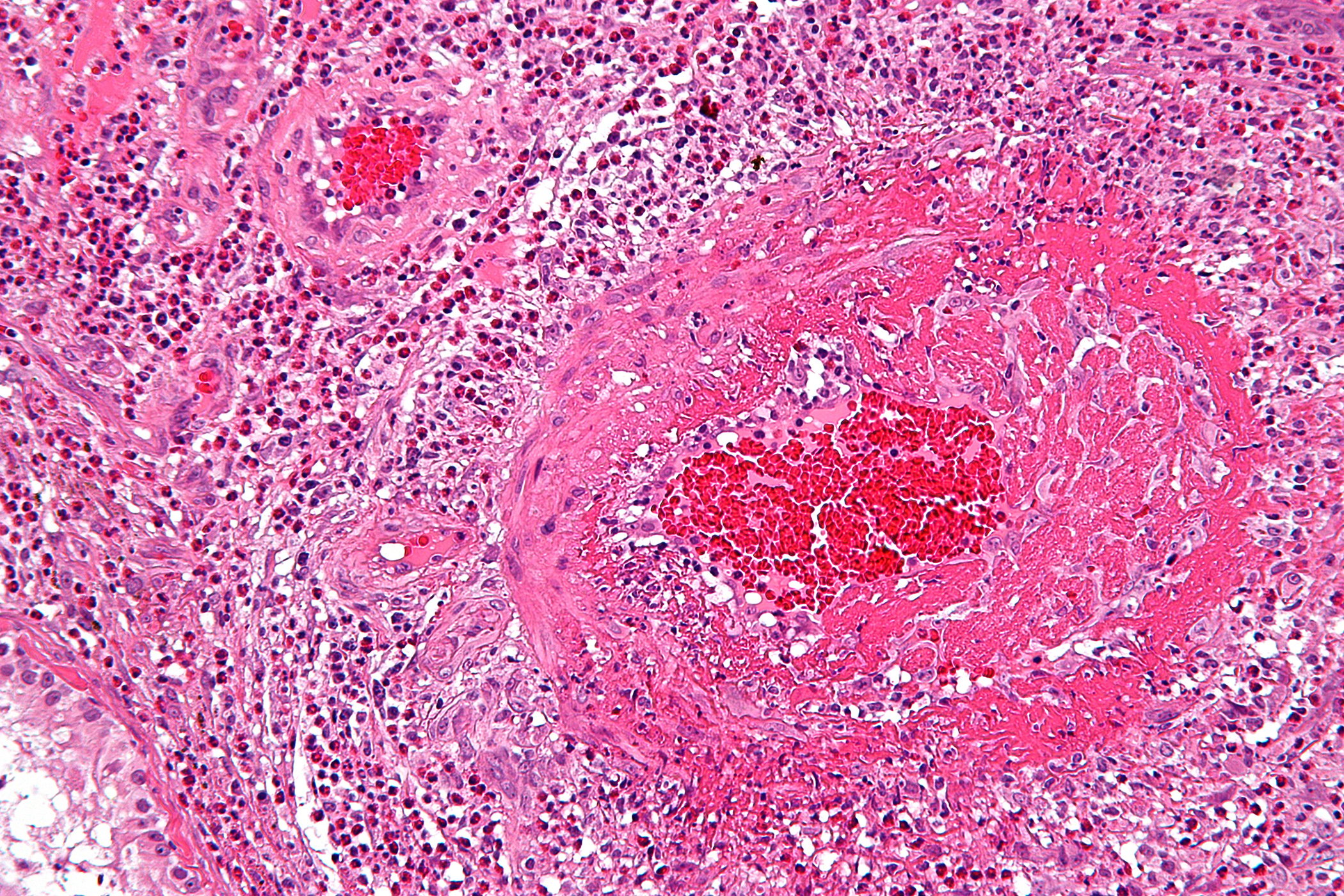

Capecitabine

Capecitabine (Xeloda®) is an antimetabolite that is transformed intracellularly as a prodrug by thymidine phosphorylase to its active compound 5-fluorouacil (5-FU). In addition to monotherapy, there is the option of combination with taxanes, vinorelbine and – in HER2-overexpressing breast carcinoma – with trastuzumab or lapatinib. Combination with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab (Avastin®) is also possible. In patients pretreated with taxanes or anthracyclines, response rates of up to 30% can be achieved with capecitabine monotherapy [6]. The most common side effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea and hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, PPE). Advantageously, hardly any myelotoxicity is to be expected, which is why capecitabine proves to be a favorable partner in combination therapy. As with vinorelbine, alopecia does not occur with capecitabine.

Dosage and course of therapy

Capecitabine is administered at a dosage of 2500 mg/m2 body surface area, divided into two daily doses, on days 1-14. This is followed by a week’s break from therapy until the 21st day. On day 22, the next cycle begins. Patients receive a consultation appointment every three weeks, during which the general condition and blood count are evaluated. Tablets are available in single doses of 500 mg or 150 mg each. In the interest of simplifying therapy, 500 mg tablets should preferably be prescribed. The calculated dose should be rounded down. The number of cycles depends on treatment response and tolerability. Special therapy diaries help with structured daily tablet intake and simplify communication between doctor and patient during the three-weekly consultations.

Oral vinorelbine is initially taken at a dosage of 60 mg/m2 body surface area once weekly. If well tolerated, dose escalation to 80 mg/m2 can be performed starting at week four. The tablets are available in dosages of 20 mg and 30 mg. Medical consultations including differential blood counts should be done on a weekly basis. Similar to capecitabine, the number of cycles is determined by response and tolerability. A therapy passport also exists for vinorelbine. Metronomic therapy (50 mg absolute on days 1, 3 and 5 every week) is currently still controversial and has not yet been approved in this form in Switzerland [7].

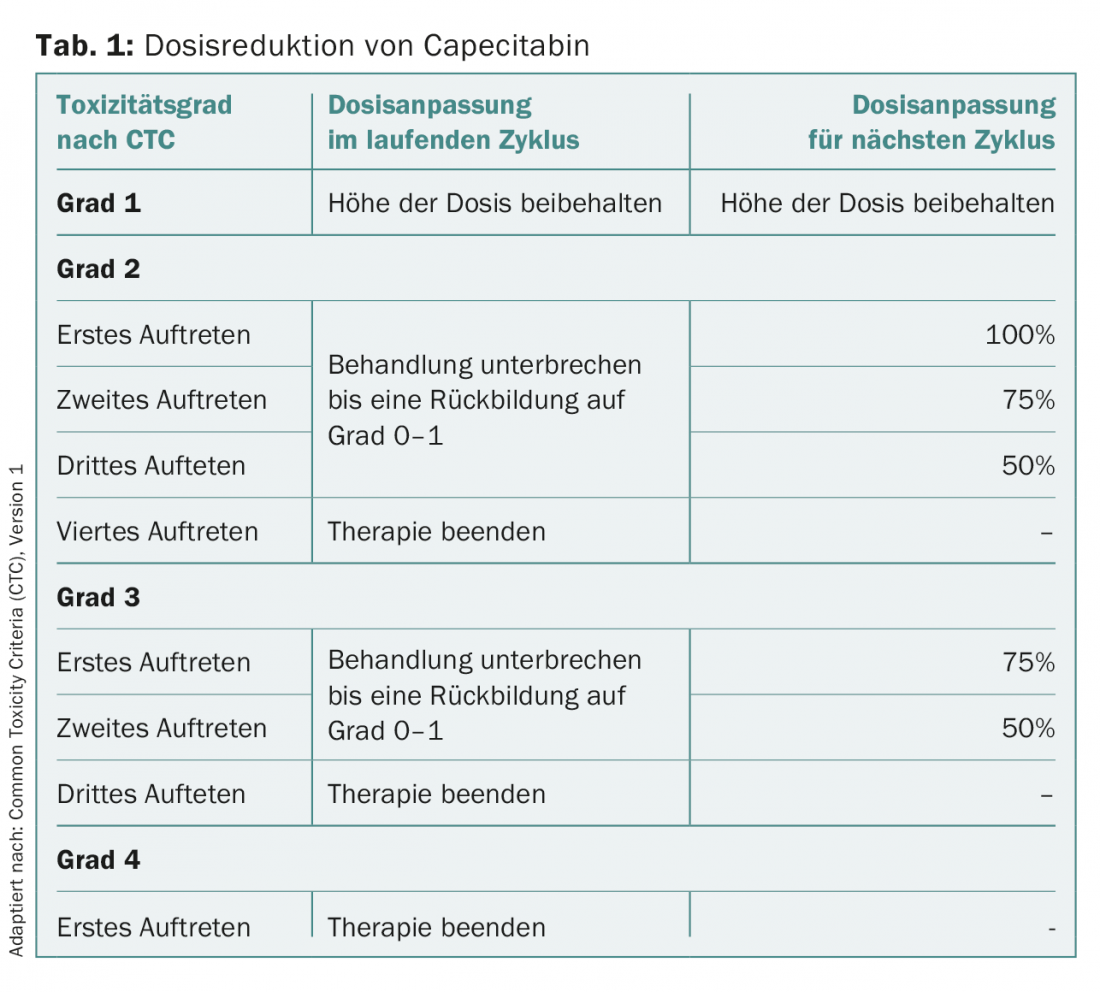

Side effect management

For prophylaxis or therapy of nausea and vomiting, administration of an HT3 antagonist (e.g., granisetron 2× 4 mg) on days 2 and 3 after dosing is recommended concomitantly with oral vinorelbine. PPE under capecitabine should be treated generously, even in early stages, with urea-containing fat cream. Higher grade toxicities with oral vinorelbine and capecitabine usually necessitate a pause in therapy until symptoms resolve. Resumption of therapy with oral vinorelbine should be initiated with min. 60 mg/m2 body surface area should be made. The dose should be escalated again quickly. For capecitabine, a toxicity-adapted regimen is used for treatment resumption (Table 1).

Selection of suitable patients

The correct use of oral cytostatic drugs is not only the responsibility of the therapists, but also depends on the patients’ intake behavior. Proper use is the key factor that maximum therapeutic benefit can be achieved for the patient. Taking the prescribed dose at the prescribed time and the precise reporting of observed side effects can only be guaranteed if the patients agree with the prescribed therapy and are convinced of the sense of the therapy. Adherence is also referred to as the patient’s willingness to adhere to the treatment recommendations agreed with the physician to the best of his or her ability, and a concordant behavior on the part of the patient and the physician. This is therefore the principle of the highest common denominator, also referred to as “shared decision making” in the Anglo-American world. This process serves to stabilize the patient. The patient is perceived as mature – also with her ambivalences – she takes an active role within a (treatment) process and becomes a trained expert for her disease. Their decisions are accepted.

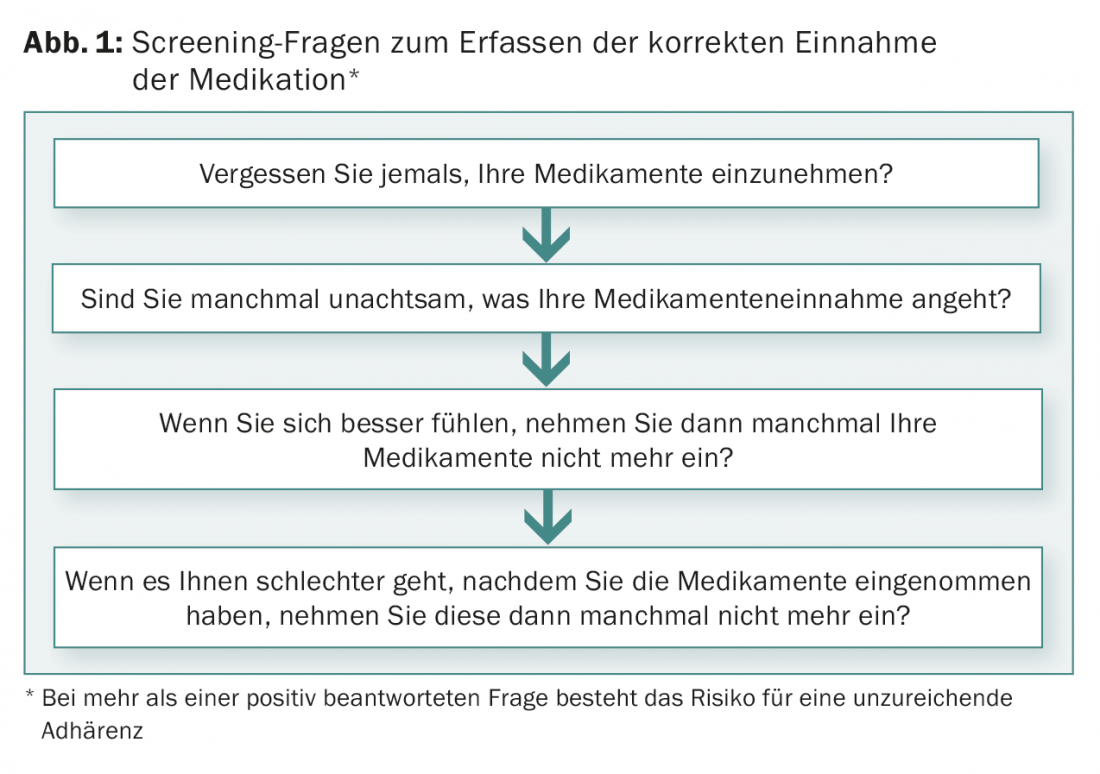

Prediction of adherence is one of the most important pretherapeutic measures to decide for or against oral chemotherapy. In addition to adherent patients (Adherers), there are Partial Adherers, Overusers, Eratic Users, Partial Dropouts, and Dropouts. Exclusively adherers will take the medication according to the agreements to the full extent at the right time, while overusers will take too high doses in the hope of an increase in efficacy and thus run the risk of dangerous side effects. Eratic users’ medication adherence is subject to wide fluctuations in the treatment cycle with negative effects on prognosis.

Various tests are available for pre-therapeutic assessment of adherence. A simple procedure consists of formulating four questions (Fig. 1). If one of these questions is answered in the affirmative, it is highly probable that there is a lack of adherence [8].

Summary

Oral chemotherapy has been an integral part of the drug treatment spectrum for metastatic breast cancer for several years. There is sufficient clinical evidence for efficacy both in combination with other agents and in monotherapy, and this also applies to advanced lines of therapy. The advantages of oral administration are the reduced time spent in medical facilities and the less invasive nature of the therapy. Venipuncture or port punctures are no longer necessary, and with them the associated pain and risk of extravasation or infection. Despite severe illness, the patients have more autonomy and thus more everyday life and normality. The low demand for human and spatial resources is reflected in reduced therapy costs for the health care system.

An important prerequisite is patient adherence, which should be checked and maintained with pre-therapeutic clarifications, regular consultations, patient-empathetic communication and seamless use of therapy diaries.

Literature:

- www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/14/02/05/key/02/05.html, incidence estimated based on data from the 12 cancer registries SG/AR/AI, BS/BL, ZH/ZG, GE, VD, NE, VS, GR/GL, TI, JU, FR, LU/OW/NW/UR.

- Gerber B, Freund M, Reimer T: Recurrent Breast Cancer: Treatment Strategies for Maintaining and Prolonging Good Quality of Life. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107(6): 85-91.

- O’Neill VJ, Twelves CJ: Oral cancer treatment: developments in chemotherapy and beyond. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 933-937.

- Husseini F, et al: Capecitabine vs Mayo Clinic and de Gramont 5-FU/LV regimens for stage III colon cancer: cost-effectiveness analysis in the French setting. Ann Oncol 2006; 17 (suppl 6): 64 (para 133).

- Martin M, et al: Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in Patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes: Final results of the phase III Spanish Breast Cancer Research Group (GEICAM) trial. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 219-225.

- Fumoleau P, et al: Multicentre, phase II study evaluating capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40: 536-542.

- Briasoulis E, et al: Dose selection trial of metronomic oral vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic cancer: A hellenic cooperative oncology group clinical translational study. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 263.

- Miaskowski C, et al: Adherence to oral endocrine therapy for breast cancer: a nursing perspective. Clin J Oncology Nursing 2008: 12(2): 213-221.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(1): 19-21.