The use of home remedies for minor health problems is common among patients in Western countries. This was also confirmed by a survey study conducted in Switzerland in 2020. In total, more than 300 patients from 15 medical practices in the Geneva region participated in the study.

One of the few European studies on the use of non-pharmacological home remedies ( NPHR) in primary care was published in 2018. This was a survey of primary care physicians [1,2]. Salt water, stretching exercises, and cold applications were considered useful NPHR but were rarely prescribed in practice. Winkler et al. 2022 illuminated the patient perspective in their study, focusing on the following [2]:

- Frequency of NPHR use among primary care patients.

- Reasons for using NPHR

- Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and NPHR use.

What is meant by “home remedies” in this context?

To avoid bias due to misunderstanding, Winkler et al. Established the following working definition: NPHRs are remedies that (i) are not available in a commercial drug formulation; and (ii) do not require external help from therapists [1,2]. Consequently, prescription drugs, as well as over-the-counter medications and phytotherapeutics (e.g., cranberry preparations, essential oils) and treatments by health professionals (e.g., physiotherapy, osteopathy) and methods of complementary and alternative medicine (e.g., acupuncture, homeopathy) were excluded [6]. Other remedies or methods were considered, such as plants or herbs, techniques, exercises, or the use of simple objects.

Methodology and implementation of the study

This study was designed as a cluster-randomized survey. Data collection took place among adult primary care patients in the waiting rooms of randomly selected primary care practices. The study population included patients 18 years of age and older who were able to provide informed consent and to read and understand all study documents in French. Patients who were in an acute emergency situation or who reported being too uncomfortable to participate in the study were excluded. The co-investigator was present in the respective waiting rooms of the consenting primary care physicians and suggested the study to the subsequent patients, informed them about the study, and obtained written informed consent before distributing the self-completed questionnaire.

Results

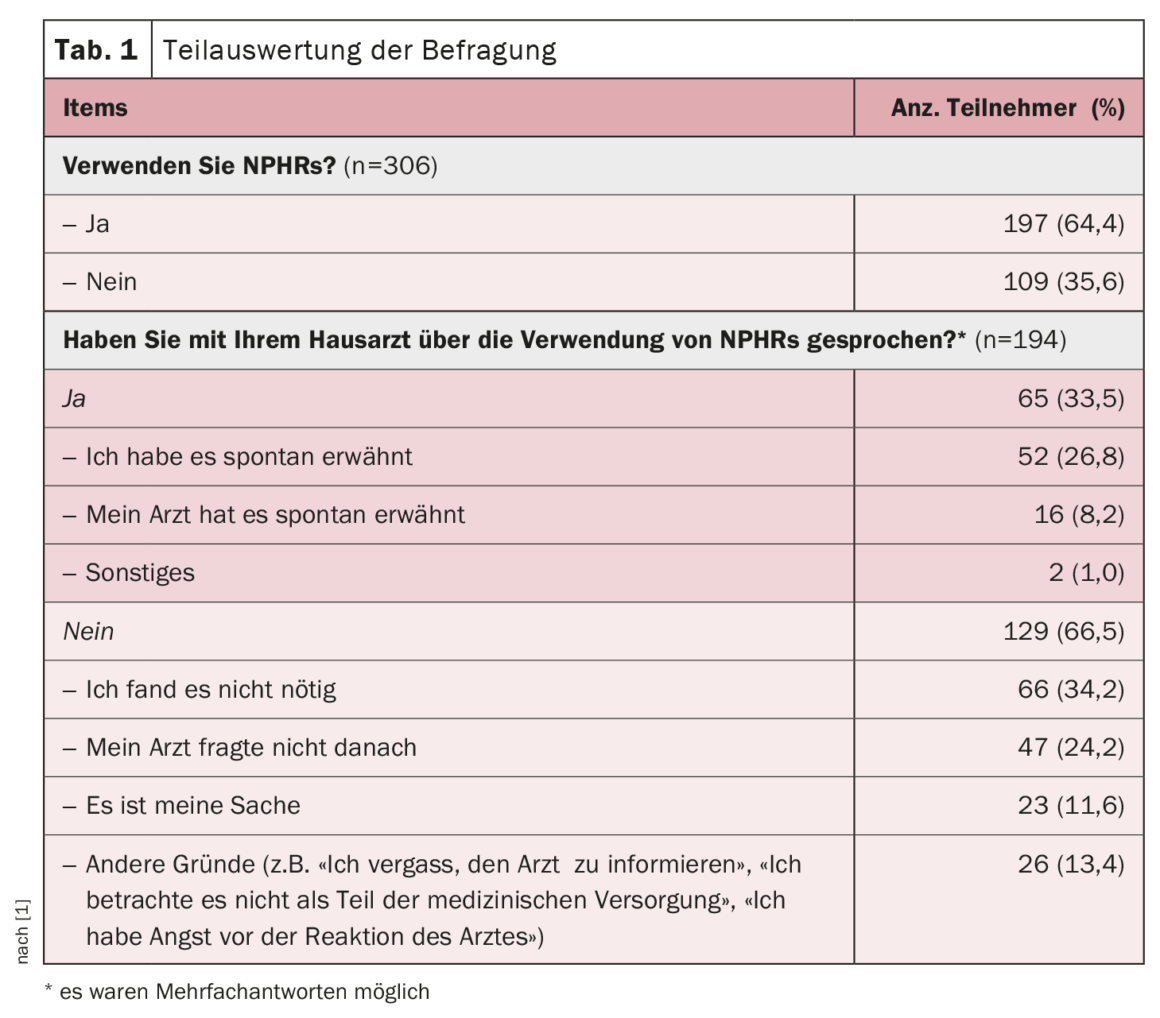

Of the primary care practices contacted, a total of 15 agreed to have the study conducted in their waiting rooms, including eight group practices and seven single primary care practices The patient participation rate was 80.5% (n=314). The average age of the study participants was 52 years. The majority of participants were female (60.5%), Swiss (71.1%), and lived in an urban area (70.7%). Nearly two-thirds (64.4%) of all participants reported using NPHR. They were mainly used for prevention (55.3%), self-treatment (41.0%), or as an alternative to conventional medicine (40.5%). The latter either to limit the number of medications taken (27.2%) or to avoid the side effects associated with medications (21.1%) and to avoid or delay a visit to the doctor (38.5%). In contrast, the main reasons for non-utilization were unfamiliarity with NPHR (48.6%), but also a desire to consult the primary care physician (38.5%) and easy access to care (35.8%).

About two-thirds of users felt that it was the primary care physician’s responsibility to inform them about NPHR, either spontaneously (36.4%) or at the explicit request of patients (32.3%), while one-third felt that it was not his or her responsibility (30.3%). Accordingly, two-thirds of users did not discuss NPHR use with their primary care physician (66.5%).

Literature:

- Winkler NE, et al.: BMC Complement Med Ther 2022; 22(1): 126.

- Sebo P, et al: Swiss Med Wkly 2018; 148(4344).

CARDIOVASC 2023; 22(2): 4

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(6): 44

InFo PNEUMOLOGIE & ALLERGOLOGIE 2023; 5(3): 24