Lowering LDL cholesterol is an important component of secondary prevention. For the first time, the “shooting stars” of lipid therapy, PCSK9 inhibitors, demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular events. The FOURIER study was therefore the main topic at ACC 2017 in Washington.

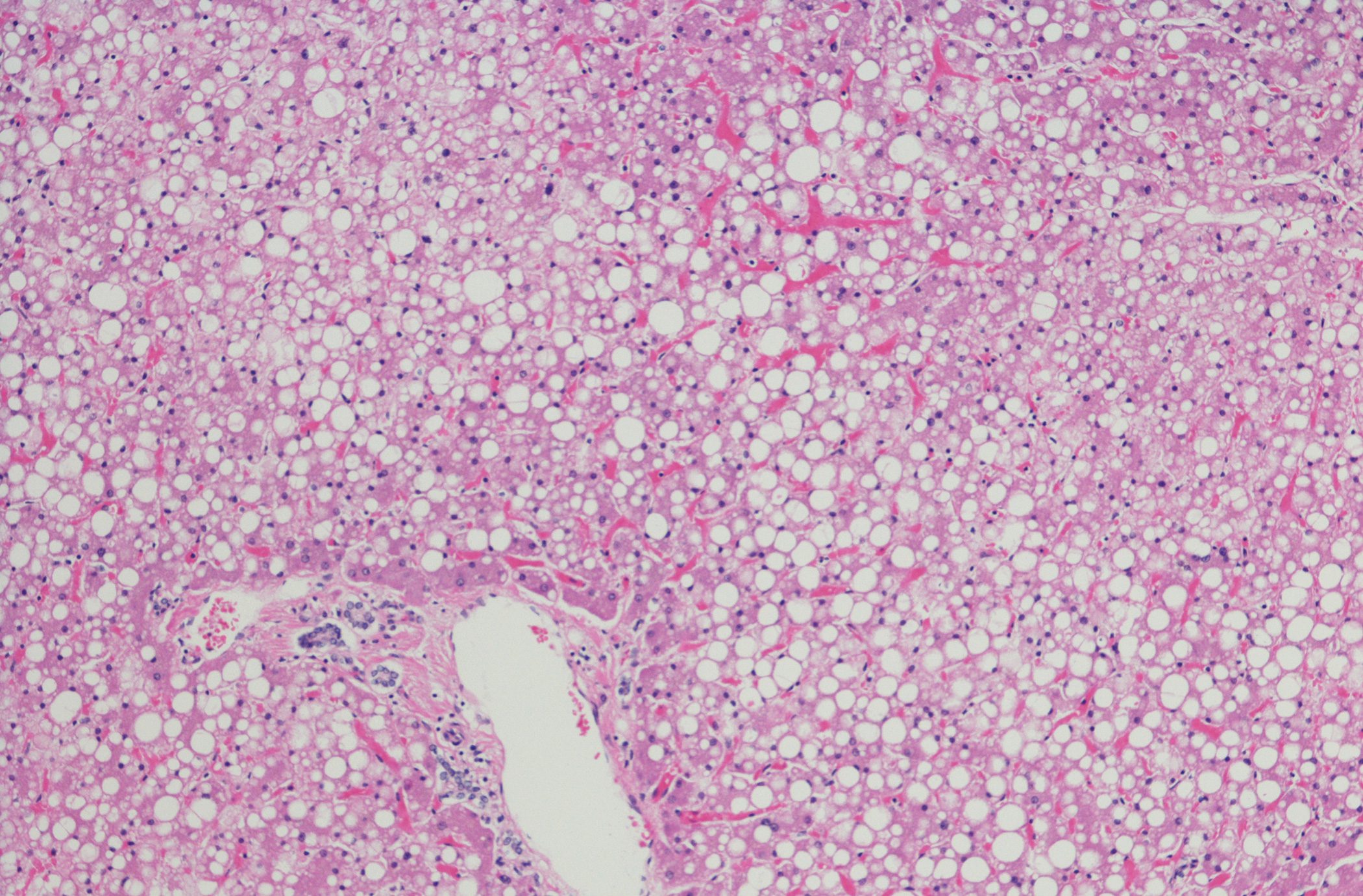

Concurrent with the presentation at the congress, the long-awaited results were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine [1]. It has been known for some time that the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab investigated in this study lowers LDL cholesterol to previously unattained levels. Like LDL, PCSK9 docks to the LDL receptors of hepatocytes. The complex formed diffuses into the cell interior, where it is completely degraded. Because this reduces the number of LDL receptors on the cell surface, fewer receptors are available for the uptake of LDL from the blood. By selectively binding to PCSK9, evolocumab increases the number of LDL receptors on liver cells, which in turn allows more LDL cholesterol to be removed from the blood. Sustained reductions in LDL cholesterol levels of 60% or more are possible. As a result, the active ingredient has also been approved in Switzerland since 2016 – as an adjunct to the maximum tolerated statin dose (with/without other lipid-lowering therapies) in adults with severe heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or with clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, as well as in adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. In each case, subject to the additional requirement of LDL cholesterol lowering.

In addition, the following sentence can be found in the original product information: “The effect of Repatha® on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been demonstrated.” Indeed, the question remained open until ACC 2017. Much was written about it, much was conjectured based on exploratory data. Now it is clear: Evolocumab is able to reduce cardiovascular event rates. The results of the phase III trial called FOURIER were received positively at the congress. However, the antibody did not reduce the mortality rate.

Risk reduction of up to 20%

27,564 high-risk patients with clinically evident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and an LDL cholesterol of at least 70 mg/dl resp. 1.8 mmol/l were randomized to receive either evolocumab (at the approved dose) or placebo over a median observation period of approximately two years – in each case as an adjunct to existing statin therapy with/without ezetimibe. On average, the participants were 63 years old and mostly male. According to the definition of clinically evident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, 81.1% had a history of myocardial infarction, 19.4% had nonhemorrhagic stroke, and 13.2% had symptomatic PAOD. Thus, this was a secondary prevention study.

Also in FOURIER, participants achieved a significant 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol with the PCSK9 inhibitor compared with placebo. This difference was, unsurprisingly, significant. At baseline, median values were 92 mg/dl (almost 70% of patients were already receiving intensive statin treatment at this time) – after 48 weeks, values were 30 mg/dl (reduction from 2.4 mmol/l to 0.78 mmol/l). Familial lipoprotein(a), which is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, was also reduced by 27% by the antibody.

Primary Endpoint: The addition of evolocumab significantly decreased the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization. Overall, the risk reduction was 15%. During the study period, such events occurred in 11.3% of patients on placebo plus statin, compared with 9.8% in the comparison group.

Secondary endpoint: Evolocumab was also significantly superior to placebo when considering the “harder” secondary endpoint, which included only cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke. Specifically, the risk here decreased by 20%. During the study observation period, 7.4% vs. 5.9% of patients experienced such events.

The extent of risk reduction by antibody administration increased over the course of the study, both in the primary and secondary endpoints. In the subcategories myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization, decreases of 21-27% were observed, whereas the risk of cardiovascular or other death, considered separately, was not lower, nor were hospitalization rates due to unstable angina.

The benefit of evolocumab was found in all major predefined subgroups (including age, sex, type of atherosclerotic disease). Patients with already low LDL levels at baseline, i.e., those with a median LDL cholesterol of 74 mg/dl (1.9 mmol/l), benefited as much as those in the highest quartile with baseline levels of median 126 mg/dl (3.3 mmol/l). The same was true for the different intensities of statin therapy (with/without ezetimibe) and for both dosing regimens of the antibody.

Safety profile convinces again

The known good safety profile was also confirmed in FOURIER: There was an equal number of (severe) adverse events or study discontinuations due to side effects under placebo and evolocumab addition. Although rare, there were slightly more injection site reactions in the evolocumab group (2.1% vs. 1.6%, p<0.001). About 90% of them were mild. There were no differences in the comparison groups with respect to new-onset diabetes or allergic reactions.

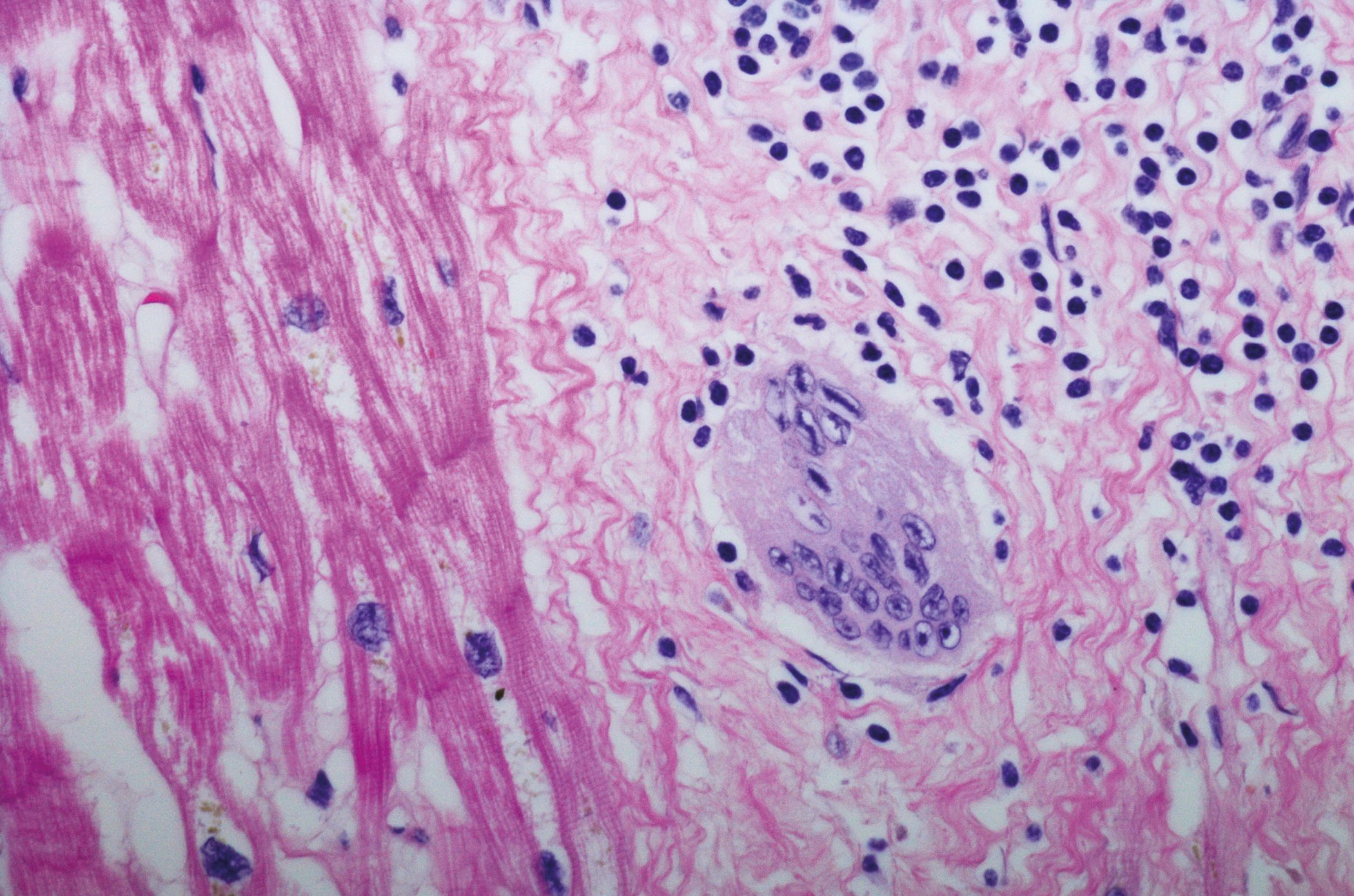

Neurocognitive events, which were followed particularly closely on the basis of previous observations, occurred at 1.6% and 1.5%, the same frequency. This contradicts the fear that particularly low LDL cholesterol blood levels have a negative effect on cognition. While cholesterol undeniably plays an important role in the normal functioning of the brain and memory. However, the brain covers its own needs, so low levels of LDL cholesterol in the blood do not create corresponding problems. Further results from the ACC from the so-called EBBINGHAUS study (with participants from FOURIER) confirm this – also for the group with extremely low values of below 25 mg/dl after the end of therapy.

Neutralizing antibodies that would lead to long-term loss of efficacy were not found (in contrast to other studies from the field).

Results under the magnifying glass

FOURIER provides extensive evidence not only for the benefits of PCSK9 inhibition but also for the hypothesis that LDL cholesterol lowering and coronary risk reduction are linearly related (“the lower, the better”). Is this sufficient to justify the not inconsiderable drug prices of the active substance class? Finally, the morbidity benefit did not translate into a significant survival benefit.

The latter is not surprising, the authors say. It was known from other studies comparing more intensive with moderate lipid-lowering therapy that additional LDL cholesterol lowering did not exert a significant effect on cardiovascular mortality. In addition, the full clinical benefit is known to occur only after a certain delay, so final conclusions are tempting.

What is certain is that the study provides for the first time data on the long-awaited (and insistently demanded) “hard” endpoints in PCSK9 inhibition. Especially the 20% risk reduction in the secondary outcome, where only irreversible events were concerned, was very positively received. The results will soon be incorporated into international guidelines for the use of this class of active ingredients. Even before the presentation at ACC, the main positive findings from FOURIER had been leaked to the public, but details were withheld until the Congress. The need of the experts to know and check the exact data was great.

The LDL levels achieved were low, in some cases even very low (at neonatal levels), which the authors interpret as meaning that patients benefit from a massive LDL cholesterol reduction far below current target levels. In the lowest quartile, values of 22 mg/dl were reached. This was done in a rather short study period for a lipid study (on average, most studies in this field take about five years) – after all, it is known that the full clinical benefit of LDL lowering only becomes apparent after a certain delay. This is also confirmed by the increasing risk reductions from FOURIER over time.

Originally, patients were to be followed for four years, but since the statistically required event rate occurred much earlier, the follow-up was shortened. So can we expect much more in the future? Some experts at Congress argued along these lines. In addition, the long-term safety of some of the patients will be examined in an extension.

There were concerns about the event rate: as mentioned, it was significantly higher than expected despite low cholesterol levels and resulted in the study being shorter than planned. Other risk factors must be involved here (in addition to LDL cholesterol, which is undoubtedly very relevant in etiological terms), and these need to be investigated in greater detail.

Target values vs. dose-adapted approach

Not least because of competing European and American guidelines, the importance of absolute versus relative lipid lowering was also a topic at the congress. “Treat to target” or “fire and forget,” was the question, as it has been so many times before. Is the benefit more closely related to the absolute reduction, as the principal investigator of FOURIER, Dr. Marc S. Sabatine, among others, suspected, or is it only related to the percentage reduction in LDL cholesterol? There is much to be said for the former interpretation, which means that the target values are once again gaining in importance. After all, if patients in the lowest quartile with a reduction from 74 to 22 mg/dl have the same benefit as those in the highest quartile with original values of 126 mg/dl, this means that the benefit per reduction is increased by 1 mmol/l down to approx. 20 mg/dl is consistent – or in other words, the event curve does not decline J-shaped, but linear. Thus, lowering as low as possible seems reasonable, as it is efficient and (as FOURIER proved again) safe.

And the cost?

The question of price remains open. Cost limits the use of the new agents, which is why they do not reach all patients who could actually benefit from them. Study director Dr. Sabatine also believes cost analyses are indicated. Real-world data could provide additional insights in this context.

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) in FOURIER was 50 after three years, so 50 patients had to be treated with evolocumab to protect one of them from the cardiovascular events mentioned. An NNT of 50 was also found in IMPROVE-IT (ezetimibe study), but much later, after six to seven years. It is likely that the event curves in FOURIER will diverge even further over this period (NNT of 30 after five years, as study leader Dr. Sabatine suspects, or even lower in high-risk groups?). This would underline the efficiency of the therapy and would tend to justify a higher price.

Consequently, the goal is to more precisely define high-risk patients who will benefit most from PCSK9 inhibition and ensure that they receive the substance they need. There was agreement on this in discussion groups at the congress. Use has been suggested primarily in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, those with (true) statin intolerance, and in very high-risk infarct patients with progressive coronary artery disease (if target values are not achieved).

Take-Home Messages

Lowering LDL cholesterol reduces the risk of future events in patients with cardiovascular disease. Under statin therapy, this relationship is well established. Since IMPROVE-IT, this has also been true for ezetimibe, a drug from a different drug class (although the overall clinical benefit was rather small). But what about the “shooting stars” of lipid therapy, the PCSK9 inhibitors? That was uncertain for a long time. The FOURIER study provides clarity and convinces the expert audience at the ACC Congress in Washington.

Source: American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2017 Scientific Sessions, March 17-19, 2017, Washington, D.C.

Literature:

- Sabatine MS, et al: Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. NEJM March 17, 2017. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664 [Epub ahead of Print].

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(2): 44-47