Four different medications are currently available in Switzerland for the prophylaxis of relapses of alcohol dependence with generally good safety and tolerability. Despite the high prevalence of alcohol dependence in the population, the disease is rarely correctly diagnosed and treated at an early stage. Despite their effectiveness, relapse-preventive medications are prescribed relatively infrequently. Relapse prophylaxis must ideally be combined with medication and psychotherapy.

Alcohol dependence is a chronic recurrent neuropsychiatric disorder with multidimensional etiology due to the interaction of physical, psychological and social factors, on the ground of genetic predisposition and neuroadaptive changes in neurotransmission circuits due to alcohol consumption. Alcoholism is one of the major health problems worldwide and also in Switzerland. Alcoholism has far-reaching consequences with physical, psychological, social and economic consequences for the person affected as well as for their fellow human beings and society. In Switzerland, about 250,000 people are addicted to alcohol, of which about two-thirds are men. This corresponds to 3.9% of the population (persons over 15 years of age) [1]. According to a study by the FOPH, every twelfth death in Switzerland is attributable to alcohol consumption (consequences of chronic alcohol consumption and accidents).

Medication for relapse prophylaxis

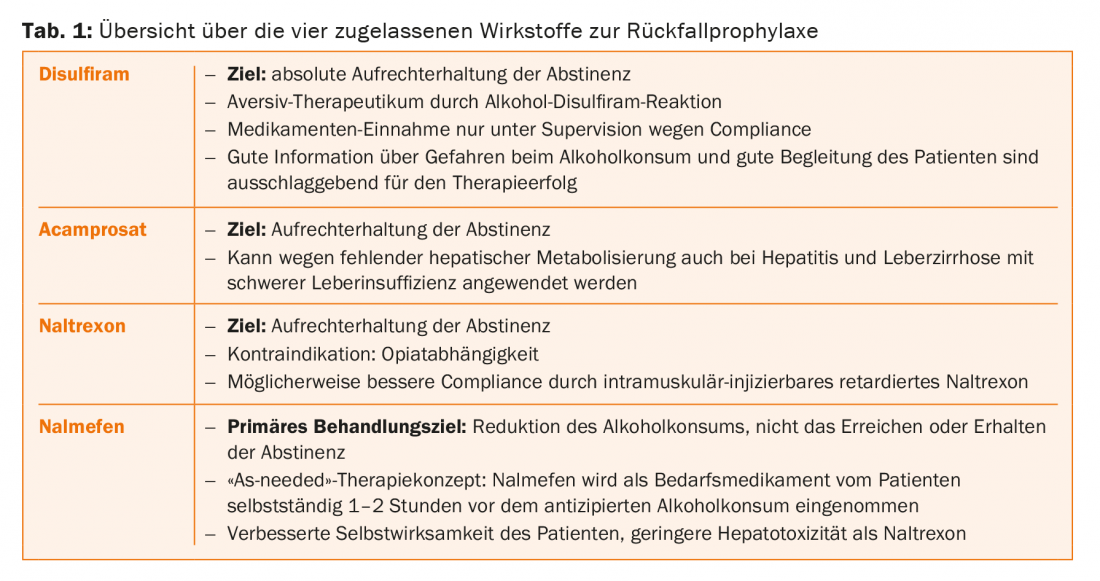

Four different medications are currently available in Switzerland for relapse prophylaxis of alcohol dependence: Disulfiram (Antabus®), acamprosate (Campral®), naltrexone (Naltrexin®) and nalmefene (Selincro®) with the “as-needed” therapy concept (Tab. 1) . Although the efficacy of these medications has been proven many times, to date only a small proportion of alcohol-dependent patients receive adequate treatment because the problem is not recognized and diagnosed, the patients and the disease are stigmatized, and physicians often lack specific expertise regarding treatment and appropriate use of relapse-preventive medications. According to a US study, less than 30% of alcohol-dependent patients are in adequate treatment, and less than 10% receive therapy with relapse-preventive medications [2].

Different types of craving

Craving refers to the addictive pressure, compulsive use, or the patient’s irresistible desire to use the addictive substance. Three different types of craving are distinguished [3]:

Reward craving: In reward craving, the focus is on the subjectively pleasant effects of alcohol consumption, which cause the dependent patient to strive for this pleasant state through the positive reinforcement effect. In this context, alcohol dependence is triggered by the reward system and is based on a dysregulation in the opiate/dopamine system. Patients with reward craving often have a family history of predisposition to alcohol dependence and an early manifestation of the addictive disorder. Patients with reward craving seem particularly amenable to naltrexone or nalmefene therapy because these agents interfere with the opiate system in a regulatory manner.

Relief Craving: Relief craving is triggered by internal states of tension, negative emotions and stress. The alcohol is used to avoid these negative states. The dependent patient thus needs alcohol as a means of repressing problems and experiencing relief from inner states of tension. Relief craving is particularly common in patients with advanced disease. This group of patients seems particularly suitable for therapy with acamprosate, since relief craving is based on dysregulation of the GABA/glutamate system.

Obsessive Craving: Obsessive craving is based on a disorder in impulse control, resulting in unplanned, impulsive drinking behavior due to loss of control. Because this is based on dysregulation of the monoaminergic system, these patients seem particularly suitable for therapy with disulfiram.

Disulfiram (Antabus®)

Disulfiram (tetraethylthiuram disulfide [TETD]) is a thiuram derivative approved as an aversive therapeutic for alcohol dependence under the trade name Antabus. Disulfiram leads to irreversible inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase in the liver and peripheral and central inhibition of dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) and hepatic microsomal enzymes [4]. Due to inhibition of hepatic aldehyde dehydrogenase, consumption of alcohol leads to accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde, resulting in an acetaldehyde syndrome within 10-30 minutes, which manifests as an alcohol-disulfiram reaction (ADR). Their symptoms include flushing due to vasodilation of the face and neck, sweating, dyspnea, hyperventilation, dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, weakness, confusion, agitation, and anxiety, as well as hypotension, tachycardia, and palpitations. Severe reactions range from respiratory depression, cardiac arrhythmias and bradycardia to circulatory decompensation with shock, acute heart failure, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest. In addition, impaired consciousness and seizures may occur [5].

Mild ADR resolves within 1-3 hours without need for medical intervention. However, no specific pharmacotherapy has yet been reported for severe ADR. The severity of ADR correlates with drug concentration and the amount of alcohol ingested. Therefore, comprehensive patient education is of tremendous importance and increases patient compliance in addition to safety. The anticipatable, highly unpleasant consequences of drinking are intended to trigger an aversive response in the patient and psychologically suppress drinking behavior [6].

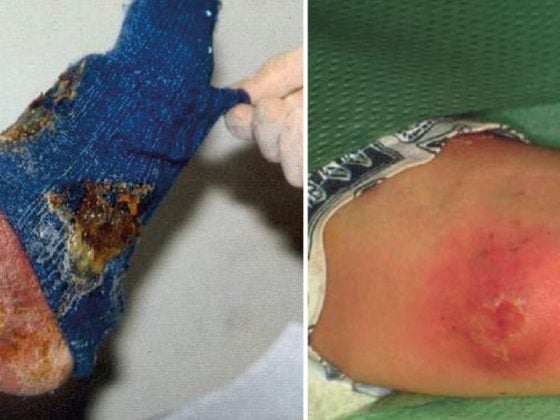

After oral intake of disulfiram, with a half-life of seven hours, the maximum plasma concentration of the drug is reached after 8-10 hours [4]. The aversive effect lasts at a daily dose of 0.2-0.5 g for 1-4 days, and in rare cases up to 14 days after the last dose. Because of the long half-life, weekly administration of 1-2 g is also possible [7]. Side effects of the substance alone, without the combination with alcohol, include fatigue, unpleasant body and mouth odor, headache, diarrhea, allergic dermatitis, sexual dysfunction, and blood pressure drop or rise [5]. Because of the increased cerebral dopamine concentration caused by inhibition of DBH, mental symptoms such as depression and manifest or paranoid-hallucinatory psychosis may rarely occur, especially in predisposed patients [8]. Dangerous side effects include lactate acidosis and toxic hepatitis (1:25,000), which occurs primarily during the first two months of therapy. Therefore, liver enzyme monitoring must be performed every two weeks for three months for early detection. If liver enzymes increase threefold, the drug must be discontinued immediately.

Contraindications to treatment with disulfiram include acute psychotic illness, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, decompensated cirrhosis, esophageal varices, hyperthyroidism, and pregnancy [9]. Due to cytochrome P-450-mediated enzyme inhibition, there may be potentiation of the effects of tricyclic antidepressants, phenytoin, warfarin, diazepam, and chlordiazepoxide.

An important prerequisite for ensuring the safety and efficacy of therapy is the controlled supervised use of the drug, because this increases compliance and psychological efficacy [10]. Under non-supervised delivery, few patients actually take the drug reliably, and it therefore has little benefit [11]. In the context of a comprehensive overall therapeutic concept with supervised intake of the drug, an impressive reduction in the risk of relapse was demonstrated by a significantly high increase in days abstinent [6,12,13]. A recent meta-analysis on disulfiram also demonstrated the superiority of supervised disulfiram therapy over nonsupervised medication use, as well as the superior treatment effect of disulfiram over naltrexone and acamprosate [14].

Because a considerable proportion of the effect is probably due to the aversive psychological aspects and regular medical supervision [10]The difference between disulfiram and placebo is only evident in the non-blinded study design, because in a blinded study the psychologically aversive effects in the two groups are blurred and thus no significant treatment effects are detectable despite clinical efficacy. [14]. On the other hand, pharmacological effects are also directly involved in the effect: For example, DBH inhibition is probably responsible for the demonstrated efficacy of disulfiram in relapse prevention of cocaine dependence and pathological gambling [15,16], and inhibition of norepinephrine formation may be responsible for the reduction of alcohol craving [17].

Treatment with disulfiram appears to be particularly effective in patients with obsessive craving (impulsive drinking behavior) [11]. Disulfiram also proved to be safe and effective in long-term treatment [18]. Therapy with disulfiram costs about CHF 13 per month (pure medication costs).

Acamprosate (Campral®)

Acamprosate (calcium bis-acethyl homotaurinate) is a derivative of the endogenous amino acid N-acetyl homotaurine, which is a neuromodulator found in the brain, and also has structural similarities to glutamate, GABA, aspartine, glycine, and taurine [5]. Like endogenous homotaurine, acamprosate is a nonspecific GABA receptor antagonist. However, the main effect is mediated by functional antagonism at the NMDA receptor (gutamatergic N-methyl-aspartate receptor), because attenuation of excitatory glutamate action inhibits glutamatergic hyperexcitability, which is partly responsible for the pathogenesis of alcohol dependence [19].

Because acamprosate modulates glutamatergic transmission, the drug is particularly suitable for patients with relief craving [20] and serves to maintain abstinence. Because of poor intestinal absorption, a short half-life of three to a maximum of eight hours, and low bioavailability, the drug must be taken in relatively high doses and at short intervals. The daily dose is 1.3-2 g, divided into three single doses of two tablets each containing 333 mg of active ingredient [5].

Side effects may include diarrhea, pruritus, fatigue, drowsiness, and headache. In general, however, the substance is well tolerated. Because of its purely renal elimination, it should not be taken in renal insufficiency. An important contraindication, due to the high calcium content in the active ingredient, is hypercalcemia. Other contraindications are pregnancy and lactation. Acamprosate has the advantage that it can be taken even in severe hepatic insufficiency because of the lack of hepatic metabolism.

Due to the very high therapeutic range, intoxications with acamprosate are extremely rare [5]. There is no potential for dependence, no increase in alcohol toxicity, and no relevant interactions. The recommended treatment duration is twelve months [21]. Meta-analyses on acamprosate showed an effect size of 0.26 with a proportion of continuous abstinence for six months of 36.1% on acamprosate versus 23.4% on placebo. The NNT is 7.5 [22]. Another meta-analysis does not estimate quite as high an effect, but recognizes acamprosate as a low-risk and moderately effective relapse prevention of alcohol dependence [21]. The cost of treatment with acamprosate is 80-100 CHF per month.

Naltrexone (Naltrexin®)

Naltrexone is a pure opiate receptor antagonist with predominant action on the μ-opioid receptor; it has no pharmacologic intrinsic effect but has a slight additional affinity for the δ- and κ-opioid receptors [5]. When alcohol is ingested, the opiate receptors are not activated, which means that the subjectively pleasant effect of alcohol cannot be perceived due to the blocked dopamine output [23]. Thus, there is a reduction in alcohol intake as relief craving in particular is lowered [24]. Treatment with naltrexone is used to maintain abstinence and reduce drinking.

After oral absorption of naltrexone, metabolization occurs in the liver (95% of the active ingredient). Despite the enormously large first-pass effect and short plasma half-life of four hours, receptor blockade lasts 72-108 hours due to its strong affinity [25]. Excretion is mainly renal.

The most common side effects of naltrexone involve the gastrointestinal tract with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of appetite. Furthermore, headache, nervousness, fatigue, sleep disturbances, anxiety symptoms and somnolence may occur. Because of hepatic metabolism, there is dose-dependent hepatotoxicity; therefore, acute hepatitis and severe hepatic insufficiency are contraindications. Another important contraindication is opiate dependence, because administration of naltrexone can induce a severe withdrawal syndrome. Pain therapy with opiates is also a contraindication. Despite the opioid antagonistic effect, depressive syndromes are extremely rare as a side effect. There is no potential for dependence [5,26] and the drug is generally well tolerated. The daily dose is 50 mg of naltrexone with one tablet.

Meta-analyses of naltrexone showed a significant relapse-preventive effect by reducing drinking frequency and severe relapse, with an effect size of 0.28 and an NNT of 7 [27]. Another meta-analysis estimated the effect to be a little lower and was able to demonstrate a reduction in alcohol use risk to 83% of the control group risk [26]. To improve compliance, the once-monthly i.m. application of sustained-release naltrexone (Vivitrol®) can also be used, but it is currently not approved in Switzerland [28]. The monthly cost of oral naltrexone therapy is approximately CHF 180.

Nalmefene (Selincro®)

Like naltrexone, nalmefene is an opiate receptor antagonist; structurally, the agents are closely related. Like naltrexone, nalmefene has antagonizing activity on the µ- and δ-opioid receptor but, in contrast, partial agonistic activity at the κ-receptor [26]. Thus, the drug has an additional impact on the dynorphin-kappa system, which plays a role in the development and maintenance of addiction [29]. Nalmefene appears to be particularly indicated in patients with reward craving, which is often associated with early onset of alcohol use disorder (before 25 years of age) and genetic predisposition (Cloninger type II) [30].

Unlike other medications for relapse prevention of alcohol dependence, nalmefene has a completely new treatment concept: the primary treatment goal is not to maintain abstinence, but to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed. In this case, nalmefene is used as an on-demand medication and is taken by the patient 1-2 hours before the anticipated alcohol consumption. After oral intake, nalmefene is absorbed very rapidly, and it leads to rapid but long-lasting receptor occupation due to its long half-life (10.8 hr, range 5.6-16 hr) [31].

The spectrum of side effects is similar to naltrexone and mainly affects the gastrointestinal tract with nausea and vomiting and the CNS with fatigue and drowsiness. However, despite similar side effects and contraindications, nalmefene is better tolerated and less hepatotoxic than naltrexone.

The innovative treatment approach of not taking a constant daily dose, but using nalmefene as an as-needed medication, is intended to promote the patient’s active participation in treatment and have a positive impact on self-efficacy because the patient decides when to take the medication (18 mg). This treatment strategy is particularly suitable for patients for whom complete abstinence does not seem realistic or who are striving for “controlled consumption”.

In a large, placebo-controlled study, the efficacy of “as-needed” therapy with nalmefene was demonstrated by significant reductions in the total amount of alcohol consumed and reductions in days with substantial alcohol consumption [32]. Clinically, nalmefene has been studied at doses of 5, 20, and 40 mg, with higher doses more commonly associated with adverse events [33]. Usually the dosage of 18-20 mg of nalmefene is used.

In a placebo-controlled study of the tolerability and safety of nalmefene 18 mg therapy, no serious complications were identified and tolerability was generally very good [34]. The only common side effect was mild and transient drowsiness and confusion. Furthermore, no differences in drug safety and tolerability were observed between the target population and the total population. Nalmefene, contrary to the pharmacological assumption, does not cause depressive symptoms or an increase in suicidality, but on the contrary has a slightly protective effect. In contrast to naltrexone, nalmefene appears to have a low hepatotoxic effect [34].

Nalmefene is still one of the newest medications for relapse prevention of alcohol dependence, so the cost of treatment is correspondingly expensive. Because nalmefene is used as an on-demand medication, monthly treatment costs cannot be provided. The cost is 105 CHF for 14 tablets of 18 mg.

Active ingredients with off-label use

Topiramate (Topamax®) is a drug for the treatment of epilepsy and the prophylaxis of migraine and cluster headache and belongs to the substance class of antiepileptic drugs. Topiramate inhibits neuronal activity by inhibiting excitatory glutamatergic AMPA receptors and by stimulating inhibitory GABA receptors. In addition, it has a modulating influence on voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels as well as on isoenzymes of carbonic anhydrase.

Because topiramate inhibits dopamine release in the corticomesolymbic system, the drug can be used off-label to maintain abstinence in alcohol dependence. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of topiramate in relapse prevention demonstrated a significant reduction in alcohol consumption and relapse risk. However, side effects such as paresthesias, taste disorders, anorexia, and impaired concentration are common with therapy [35].

Baclofen (Lioresal®) is a derivative of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and belongs to the group of central muscle relaxants. As an agonist to the GABAB receptor, it inhibits motor neuron excitation by inhibiting excitatory presynaptic transmitter release. In addition, however, motor neurons are also directly postsynaptically inhibited by baclofen. Because of its inhibition of mesocortical dopaminergic neurons, baclofen can also be used off-label for relapse prevention of alcohol dependence.

Due to the short half-life of 3-4 hours, the drug must be taken three times a day. Single doses are increased, starting at 5 mg (=15 mg/d), by 5 mg at a time until a daily dose of 30-80 mg/d is reached. Common side effects include ataxia, confusion, sedation and drowsiness, and sleep disturbances. In overdose, respiratory depression and epileptic seizures occur; in withdrawal, muscle weakness, anxiety symptoms, and hallucinations occur. The active ingredient is eliminated purely renally [36]. The drug is generally well tolerated and can also be used as second-line therapy in patients with severe hepatic insufficiency and alcoholic hepatitis if they are resistant to acamprosate [37]. The clinical efficacy of baclofen has been demonstrated in several double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials by a reduction in craving and a significantly lower relapse rate [37–39].

Other substances

Other drugs that may be considered as potential candidates for pharmacological relapse prophylaxis of alcohol dependence, but whose efficacy has not yet been sufficiently well established, are the anticonvulsants/pain modulators gabapentin and pregabalin, the antiemetic ondansetron, the cannabinoid receptor antagonist rimonabant (again withdrawn from the market), the antidementive memantine, and various antidepressants (fluoxetine, sertraline) and neuroleptics (quetiapine). The use of varenicilin as a partial acetylcholine receptor agonist for tobacco cessation or prazosin, an α-receptor antagonist, is also discussed. Possible candidates also include CRH antagonists, neuropeptides of stress regulation, or ALDH-2 antagonists [5].

Combination treatments

Because the drugs acamprosate, naltrexone/nalmefene, and disulfiram target pharmacodynamically different targets, combination treatment could have additive or even potentiating efficacy. Previous combination treatment studies have found no serious interactions, and tolerability has generally been good. However, the study situation is still insufficient.

Acamprosate and naltrexone: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed improved efficacy of combination treatment over placebo and monotherapies with acamprosate or naltrexone [40]. However, this result could not be reproduced in two other studies [41,42].

Naltrexone and disulfiram: Three separate studies failed to demonstrate additive or even potentiating effects of combination treatment [43–45].

Acamprosate and disulfiram: a controlled multicenter study showed better efficacy of combination treatment over monotherapies by extending abstinence duration [46]. No drug-drug interactions were detected.

Literature:

Only the most important sources are mentioned below. All other sources mentioned can be requested from the author.

2. Jonas DE, et al: Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014; 311: 1889-1900.

3. Verheul R, et al: A three-pathway psychobiological model of craving for alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol 1999; 34: 197-222.

5. Soyka M: Update Alcohol Dependence – Diagnosis and Therapy. UNI-MED 2013, 2nd ed; 103-113.

6. Mutschler J, et al: Recent results in relapses prevention of alcoholism with disulfiram. Neuropsychiatr 2008; 22: 243-251.

14. Skinner MD: Disulfiram Efficacy in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9(2): e87366.

18. Mutschler J, et al: Safety and efficacy of long-term disulfiram aftercare. Clin Neuropharmacol 2011; 34: 195-198.

21. Rösner S, et al: Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (9): CD004332.

22. Mann K, et al: The efficacy of acamprosate in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol-dependent individuals: results of a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004; 28: 51-63.

26. Rösner S, et al: Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Dateabase Syst Rev 2010; 12: CD001867.

27. Srisurapanont M, et al: Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of rendomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2005; 8: 267-280.

28. Garbutt JC, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 1617-1625.

32. Mann K, et al: Extending the treatment options in alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled study of as-needed nalmefene. Biol Psychiatry 2013; 73(8): 706-713.

34. Wim B, et al: Safety and tolerability of as-needed nalmefene in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the phase III clinical program. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015; 14(4): 495-504.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(5): 8-13.