Travel is steadily increasing worldwide: while there were 150 million tourist arrivals in 1970, this number rose to over 940 million in 2010 [1]. On average, each Swiss person took 2.8 trips in 2012; 20.3 million trips were made in total, of which 12.9 million were abroad. The characteristics of travelers have changed in recent years. Traditional tourist trips are decreasing proportionally, and increasingly trips are made by people visiting friends and relatives in their former home countries (‘visiting friends and relatives” VFR) [1]. This article is intended to provide an overview of the classic travel medicine topics, but also to highlight the changing epidemiology among travelers and to promote risk-focused counseling in practice.

In Switzerland, “visiting friends and relatives” (VFR) account for 17% of all travelers [2]; in the UK, VFR already account for about 50% of all travelers when traveling to Africa or the Indian subcontinent. Increasingly, older persons with comorbidities are taking trips to subtropical or tropical areas. Especially these two groups of travelers have some peculiarities and need the special advice.

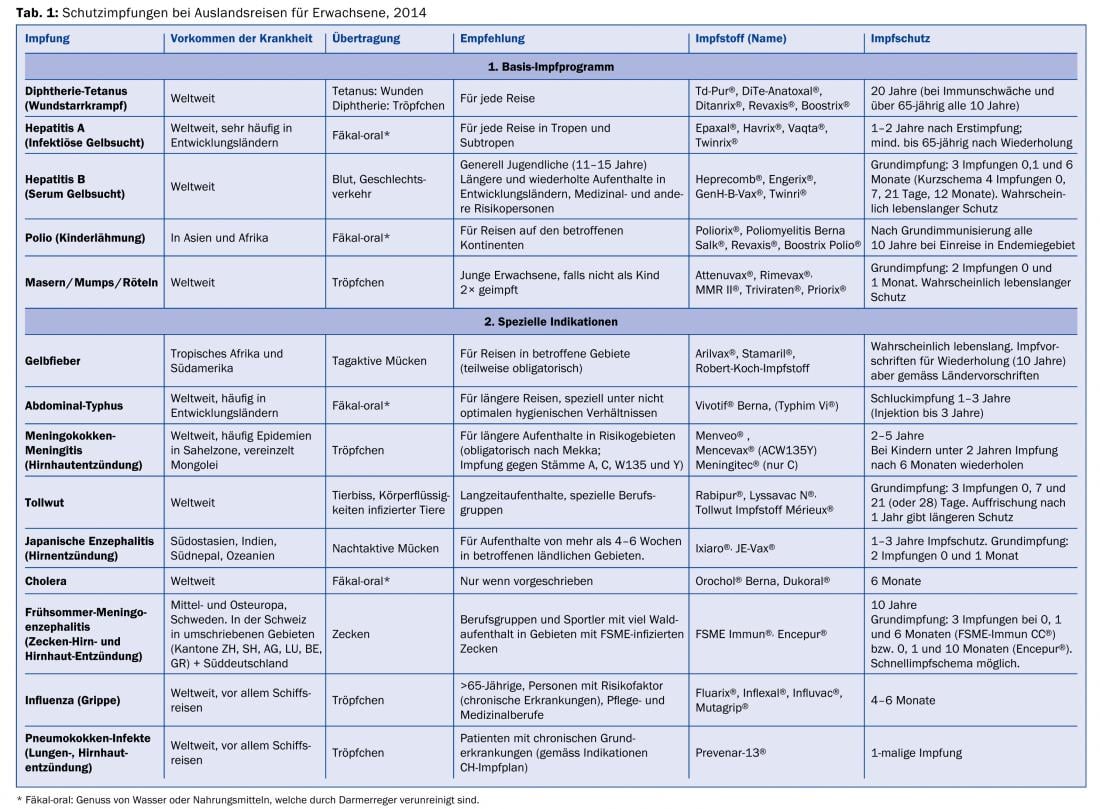

Furthermore, travel counseling can and should be taken as an opportunity to evaluate the completeness of basic vaccinations (especially MMR) and any recommended vaccinations in risk groups (e.g., pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in patients with chronic comorbidities, according to the Swiss Vaccination Schedule [3]). Table 1 provides an overview of this.

For a meaningful individual consultation, the health condition of the travelers (age, diseases, pregnancy, allergies, medication, etc.) must be known. We need to know the destination, how long they stay in specific risk areas, and how they travel (group vs. individual tourism, travel mode, and accommodations). An appropriately designed questionnaire can be completed by travelers prior to the consultation; this can greatly facilitate the consultation and save meaningful time.

Travel risks

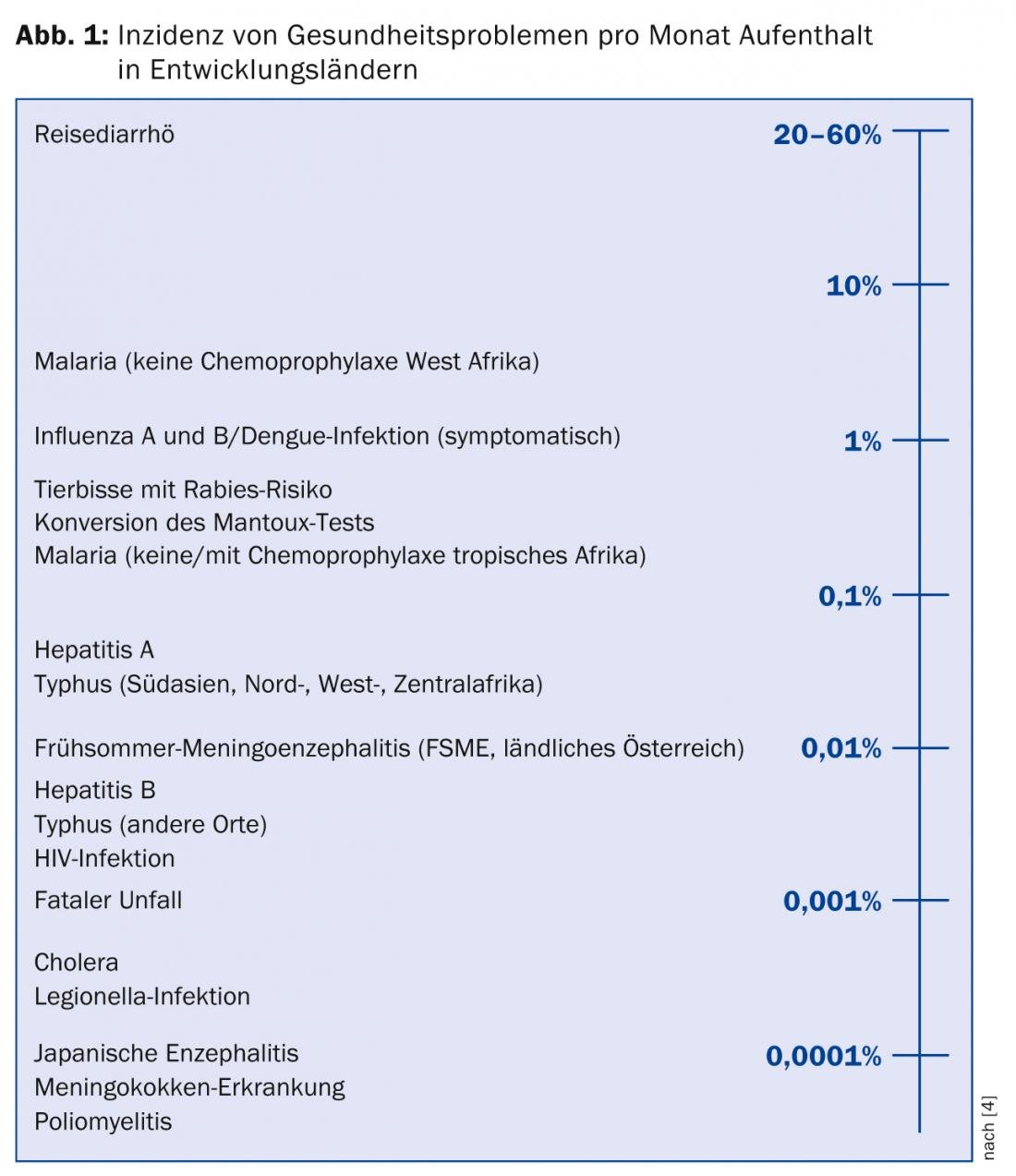

In all publications on travel-associated diseases, travelers’ diarrhea is the main complaint – with an impressive incidence rate of up to 60% already within the first two weeks. Traveler’s diarrhea is usually harmless and lasts a few days, with half of travel-associated diarrhea resolving spontaneously after 48 hours. Special risk groups for traveler’s diarrhea are children and young adults (<30 years), persons on antacid treatment, and those with pre-existing gastrointestinal disease or immunodeficiency. In the “risk axis” of Steffen et al. [4] lists the risks per month of travel: Traveler’s diarrhea is followed by the risk of contracting malaria when traveling to West Africa without malaria prophylaxis, with an incidence of 3% per month, followed by influenza and the risk of suffering a dog bite with rabies risk (Fig. 1).

Travel mortality is largely dependent on age and, for younger travelers, on their activities. In an analysis of 89 521 ill travelers treated at GeoSentinel clinics, specialized travel medicine clinics on all continents worldwide, 8.4% of travelers were over 60 years of age [5]. Compared with the comparison population of 18- to 45-year-olds, this group of travelers had a significantly increased risk of being treated for pneumonia/bronchitis or heart failure. In contrast, the most common reasons for medical treatment among younger travelers were malaria and dengue infections. Mortality was 45/100,000 in the younger population and 199/100,000 in the older population, with increasing risk with each decade over age 60.

In an analysis [6] of causes of death in Chiang Mai City, Thailand, 7.9% of all deaths were foreigners, with an average of six foreign deaths per month. The median age of foreigners at death was 64 years; accordingly, cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of death, followed by neoplasms and finally infectious geneses. 10% of all causes of death were traumatic (accidents, suicides, drug overdose, and drowning). The standardized mortality rate did not differ from that in the travelers’ countries of origin – so what you die of most often at home, you die of abroad. Two studies of deaths of Scottish and Canadian citizens traveling, respectively, showed similar main findings: three-quarters of all deaths had a natural cause. However, in these two studies, traumatic deaths, mainly traffic accidents and suicide and homicide, were higher, about 20%. These were the leading causes of death among younger travelers.

Special travelers

It is therefore of great importance that travel advice is geared to the age and risk profile of the travelers. The risk of traumatic causes of death and their prevention are often neglected in travel counseling.

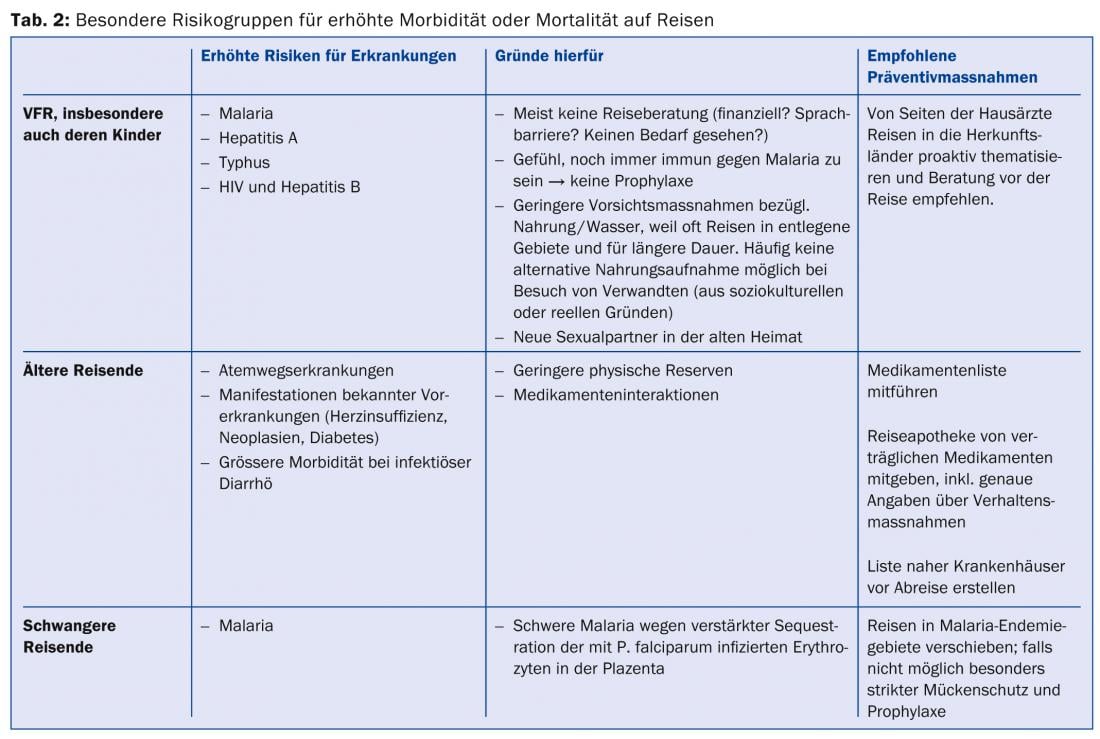

Table 2 lists some specific groups of travelers and their particular risks. VFR and especially their children are the travel group with the highest morbidity in many studies [7]. VFRs now account for 21-68% of all imported malaria cases [8] and by far the major group of imported hepatitis A and typhoid fever cases. When counseling elderly travelers with comorbidities and comedications, interactions with travel prophylaxis (e.g., risk of QTc prolongation of some antimalarials) must be considered. In the presence of diarrhea and decreased food intake, individuals on antihypertensive or oral antidiabetic therapy should be instructed to adjust it for the duration of symptoms, otherwise dangerous hypotension or hypoglycemia may be provoked. Due to the particular risk of severe malaria, pregnant women should be advised against travel to malaria endemic areas if possible.

Useful tools in travel consulting

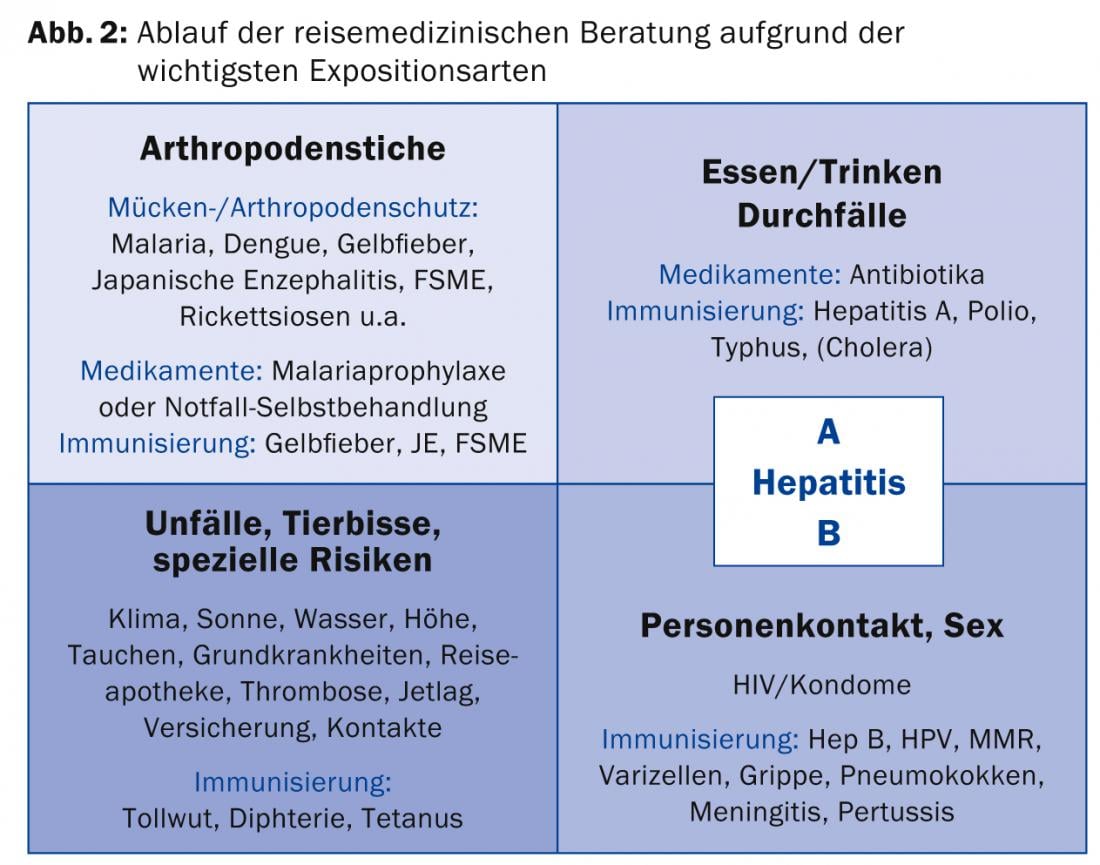

There is usually little time available for advice tailored to the individual risks of travelers, which is why travel advice is often reduced to just vaccination and malaria advice. It is helpful to recommend preventive measures as exposure-specific packages (Fig. 2).

These, of course, include the vaccination recommendations and the measures to prevent malaria morbidity, but they go well beyond them. In order for these exposure-based packages to be reasonably and efficiently offered to travelers, broad baseline knowledge and continuous updates on epidemics occurring around the world are essential. First of all, it is helpful to have an updated database of epidemiological situations, regulations and recommendations depending on the destination and time of travel. Tropimed®, other databases such as Safetravel® or the recommendations issued by the Federal Office of Public Health or the respective state authorities are recommended. The ProMED mail website (www.promedmail.org) provides more geographically detailed information on local epidemics. Further information material can be given to the traveler in the form of summary sheets per disease/risk due to limited time. In addition, we have written a small booklet “Safe Travel” (ISBN 978-3-905708-84-4), which can also be given to travelers. Likewise, a list with practical information on the vaccinations recommended in travel medicine is very helpful for a quick overview (Tab. 1).

Concrete procedure

We recommend a consultation (Fig. 2) that considers the following four main exposures according to the specific risks of the travelers and the travel destination: Arthropod bites; food, drink, and diarrhea; person contact incl. Sex; accidents, animal bites and special risks.

When this scheme is gone through, the consultation is complete. The focus of the consultation is set individually according to the travel destination.

Arthropod bites: Efficient mosquito protection, i.e. the correct use of impregnated mosquito nets, clothing as well as repellents is strongly advised. In addition to malaria, this protection covers a variety of diseases such as early summer meningoencephalitis, rickettsial fever, dengue and chikungunya fevers, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, “Ross River” and other mostly viral fevers. To this end, notes on diurnal activities of arthropods (Anopheles vs. Aedes, ticks) are provided.

Eating/drinking and diarrhea: As mentioned earlier, diarrhea is the most commonly reported health complaint by travelers. Few travelers adhere to the classic advice of “cook it, boil it, peel it or forget it,” which explains the high incidence of up to 60% traveler’s diarrhea mentioned above. Nevertheless, basic hygiene tips should be taught in any case. Emergency antibiotic therapy may be given to elderly travelers and to travelers of any age with pre-existing underlying gastrointestinal disease or immunosuppression. Currently, quinolones for Africa and azithromycin for Asia and Latin America are such drugs, although rapidly increasing resistance of intestinal pathogenic bacteria worldwide is challenging the effectiveness of emergency antibiotic therapy. At this point, the indication for hepatitis A and typhoid vaccination can be discussed.

Person-to-person contact, sex: combination vaccination for hepatitis A and B eases the transition into the topic of sexually transmitted diseases. “We’ve now talked about infectious jaundice hepatitis A, which is transmitted through eating and drinking. Another even more dangerous jaundice, hepatitis B, is primarily sexually transmitted.”

The risk of sexually transmitted diseases is high among travelers. 20% of travelers reported new sexual contacts during their travels, of which 49% did not use condoms [9]. It is also worth mentioning that 34% of all new HIV diagnoses among heterosexual Swiss and 19% of the same among homosexuals are acquired abroad [10].

Other diseases can also be transmitted from person to person outside sexual contact. The indication of appropriate vaccinations such as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), varicella, pertussis, meningococcal meningitis, influenza, and pneumococcal can be discussed in this context. With particular emphasis, the opportunity can be taken here to catch up on or complete the basic MMR vaccination – especially in light of the fact that Switzerland is a major measles exporting country. This “export activity”, especially to poorer countries, is shameful, as measles often leads to particularly severe courses in local people there.

Accidents, animal bites, and special risks: Accidents, sunburn and altitude sickness are common causes of morbidity during travel. As mentioned above, accidents among younger travelers are also the leading cause of death during tropical travel. Travelers are encouraged here to choose the safer travel option when in doubt, and to interrupt the trip if necessary if the driver exhibits a risky driving style.

Potential rabies exposures from animal bites are not uncommon, and pre-exposure rabies immunization is indicated for extended travel to rabies high-endemic areas. Tetanus and diphtheria vaccination coverage is also evaluated during this portion of the consultation.

Summary

Exposure-based travel counseling is efficient and allows for an understandable individualized consultation. A simple graphical scheme ensures completeness and consistency of advice and proves especially useful in practices where more than one person is involved in travel advice.

Cornelia Staehelin, M.D.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Travelers to their original countries of origin (“visiting friends and relatives”) are least likely to seek pre-trip counseling, but are most likely to contract malaria, typhoid, or hepatitis A.

- Elderly travelers must receive special advice, in addition to the usual travel advice, regarding behavioral measures in case of possible complications of their underlying diseases while traveling.

- Younger travelers are particularly at risk for accident-related complications.

- Sex while traveling: safer sex rules are often left at home while traveling – 20% of travelers have a new sexual partner while traveling; condoms are not used in half of these contacts.

A RETENIR

- Les voyageurs qui se déplacent vers leurs pays d’origine (” visiting friends and relatives “) sont ceux qui consultent le moins souvent avant le voyage, mais souffrent le plus fréquemment de malaria, de typhus ou d’hépatite A.

- Les voyageurs plus âgés doivent bénéficier d’un conseil particulier en plus de la consultation de voyage classique en raison des conduites à tenir en cas d’éventuelles complications de leurs maladies préexistantes en voyage.

- Les jeunes voyageurs sont particulièrement à risque de souffrir de complications liées à un accident.

- La sexualité en voyage: les règles de prudence en matière de sexualité souvent oubliées à la maison lors des voyages – 20 % des voyageurs rencontrent un nouveau partenaire sexuel en voyage; la moitié de ces contacts s’effectue sans protection.

Literature:

- Leder K, et al: Travel-associated illness trends and clusters, 2000-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19(7): 1049-1073.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Travel by the Swiss resident population 2012.

- Federal Office of Public Health: Swiss Vaccination Plan 2014.

- Steffen R, Amitirigala I, Mutsch M: Health risks among travelers – need for regular updates. J Travel Med 2008; 15(3): 145-146.

- Gautret P, et al: Travel-associated illness in older adults (>60 y). J Travel Med 2012; 19(3): 169-177.

- Pawun V, et al: Mortality among foreign nationals in Chiang Mai City, Thailand, 2010 to 2011. J Travel Med 2012; 19(6): 334-351.

- Behrens R, Barnett ED: Visiting Friends and Relatives. In: Keystone J (ed.): Travel Medicine.2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier 2008; 292-298.

- Pavli A, Maltezou HC: Malaria and travelers visiting friends and relatives. Travel Med Infect Dis 2010; 8(3): 161-168.

- Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter PR: Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14(10): e842-e851.

- Federal Office of Public Health HIV and AIDS Section: HIV & STI Statistics and Analyses 2012. 27-5-2013.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(6): 12-18