In 2019, the new S1 guideline “Prehospital airway management” was published. Preoxygenation and mask ventilation are of central importance. Two studies have provided clear answers to this.

Intubations in the intensive care unit are very often accompanied by complications, some of them severe. Most often, doctors are dealing with a drop in oxygen saturation, and cardiac problems are the result. In this regard, researchers from France and the United States have studied preoxygenation during intubation using high-flow oxygen therapy and compared it with non-invasive ventilation (NIV).

In the multicenter FLORALE-2 trial [2] from France, patients in 28 intensive care units with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg) were randomized to a NIV arm (n=142) and a high-flow O2 arm (n=171) for preoxgenation. The performance before intubation lasted 5 minutes with 100% oxygen, and the primary end point was severe hypoxemia, situations in which there was a drop in saturation below 80%. This endpoint was documented in 23% of the NIV patients and 27% of the HFNC group.

However, the situation was different in the subgroup of those patients who had more severe baseline hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 <200 mmHg). Here, a statistically significant difference in favor of noninvasive ventilation was observed. When oxygen was administered with high-flow alone, 35% (n=44) fell with desaturation; in the NIV group, this was the case in only 24% (n=28) (fig. 1).

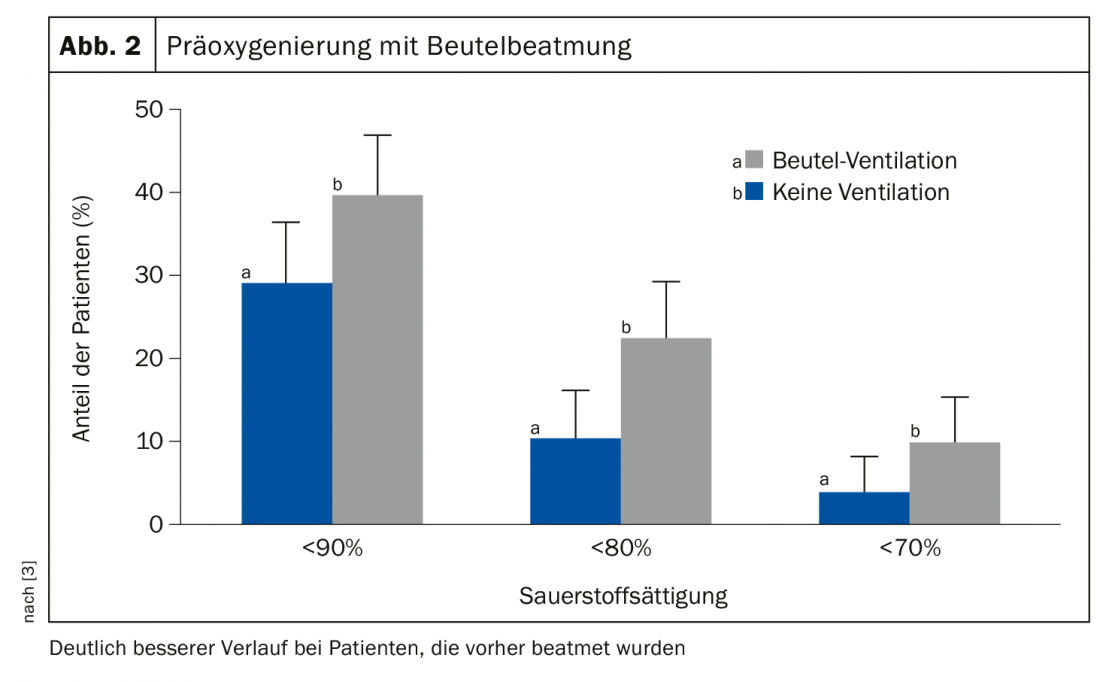

Another study [3] also looked at this issue and asked a very simple question: Does preoxygenation with bag ventilation make sense or is it dangerous? In the intensive care setting, 40% of all intubations result in critical hypoxemia, with cardiac complications, hemodynamic instability, or even resuscitation and death as a consequence.

The nonblinded, randomized, multicenter study included 401 adult patients in 7 US ICUs with an indication for intubation (but those with an indication for emergency intubation and/or increased risk of aspiration were excluded). Patients had a median age of 60 years, 50% had sepsis or septic shock, and 60% had hypoxic respiratory failure.

Patients were divided into a group that received bag ventilation with an oxygen rate of >15 l/min and positive end-expiratory pressure of 5-10 cm H2Oat 10 breaths/min before intubation (n=199) and a control group that received no ventilation but 77.7% received supplemental oxygen via oxygen mask (n=202). The result was clear: those patients who had previously received active ventilation showed a significantly better course. The proportion of patients who showed desaturation was significantly lower here. And, there was no significantly meaningful difference in the frequency of aspirations in the bag (2.5%) versus control (4%) group-although this must be considered in light of the fact that patients at high risk for this were excluded from this study (Fig. 2).

In summary, both studies demonstrate the usefulness of preoxygenation before intubation, as also called for in the guideline. Whether NIV or HFNC is used for ventilatory support is not entirely central. It is crucial that a sufficiently high oxygenation of the organism is achieved in any case.

Source: Pneumo-Update Mainz (D)

Literature:

- Timmermann A, et al: S1 guideline prehospital airway management 2019.

- Frat JP, et al: Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 303-312.

- Casey JD, et al: N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 811-821.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(1): 28-29.