The dermatological societies emphasize the need for skin cancer prevention and it is increasingly also an issue on the health policy agenda. Identifying risk factors for melanoma and white skin cancer, informing about possible measures and debunking myths are just a few aspects. An overview of the most important current facts on UV exposure, screening, treatment options and much more.

Skin cancer is divided into black skin cancer, melanoma, and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). NMSC refers on the one hand to the large group of white skin cancer, which originates from the epithelial cells of the skin and includes basal cell carcinoma (basal cell carcinoma/BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma/SCC, and on the other hand to the less common Merkel cell carcinoma, sarcoma and lymphoma.

The terms prevention and precaution are used synonymously. This refers to all medical and social efforts to promote health and prevent diseases and their consequences. Prevention is divided into primary prevention, secondary prevention and tertiary prevention. While primary prevention attempts to prevent the development of a disease through various measures, secondary prevention is understood to mean early detection through screenings and preventive examinations. The aim of tertiary prevention is to prevent the progression of diseases that have already occurred and thus to treat them at an early stage and prevent recurrences [1].

In the context of skin cancer, prevention consists of the following three pillars:

- Information and education about UV radiation, the development of skin cancer and protective measures such as physical, chemical and textile light protection.

- Regular clinical screening and reflected light microscopic skin screenings

- Early treatment of precancerous skin lesions or in situ tumors using surface procedures or minimally invasive procedures for basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma

Primary prevention

The key facilitators of primary prevention are the primary care physician and dermatologist, as well as communities, advocacy groups, and policy makers. The tasks of general practitioners and dermatologists in primary prevention are to identify at-risk individuals and risk behaviors, to raise awareness of the dangers of the sun or UV light, and to educate patients on the correct use of sun protection, which is based in particular on skin type and UV index. Stakeholders and municipalities conduct health policy by informing the population and defining preventive medical actions in the field of leisure and work.

Dangers of UV rays and development of skin cancer

The solar radiation consists of 4% UV radiation. UV rays are invisible electromagnetic wavelengths from 30-400 nm and are divided into long-wave UVA (400-315 nm), medium-wave UVB (315-280 nm) and short-wave UVC (280-100 nm). While UVA is mainly responsible for premature skin aging and wrinkling in addition to triggering light dermatoses, its contribution to skin carcinogenesis is via indirect DNA damage by photooxidation and formation of oxygen radicals. Photocarcinogenesis of UVB radiation leads via direct interaction with DNA to the formation of pyrimidine dimers and thus to mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene and consequent failure of damaged cells to undergo apoptosis. 60-100% of all basal and squamous cell carcinomas have mutations in the p53 gene. Photocarcinogenesis is further enhanced by UV radiation inducing general immunosuppression, which is also used in phototherapy. UVB is particularly still responsible for the development of erythema solare and physiological light callosity (epidermal hyperplasia with histological acanthosis and hyperkeratosis). Danger from UVC exists especially in high mountain areas and due to the risk of triggering keratoconjunctivitis photoelectrica [2].

50% of lifetime UV exposure occurs during midday hours between 11-14 . Severe sunburns before the age of 15 increase the risk of melanoma by a factor of 3 to 5. UV light is thought to play an initiator and promoter role in melanoma development, with the exception of lentigo maligna melanoma. However, artificial UV radiation from tanning bed use at a young age also increases the risk of cancer of BCC by 30%, SCC by 70%, and melanoma by 60%.

Skin types and UV index

There are 6 skin types according to Fitzpatrick, based on the genetically determined degree of pigmentation of the eumelanin of the skin and the ability to react to UV radiation with an adjustment or increase of melanin. In Central Europe and Switzerland, skin types II and III are most common, followed by skin type IV in people of southern (e.g. Italian) descent and skin type I from northern European countries, respectively. The more melanin the skin has, the higher the self-protection time, which is defined as the amount of time to be exposed to the sun without being protected and without turning red at a UV index of 8. This can vary from a few minutes for skin type I to about 40 minutes for skin type IV. Table 1 describes the 6 skin types and the self-protection time.

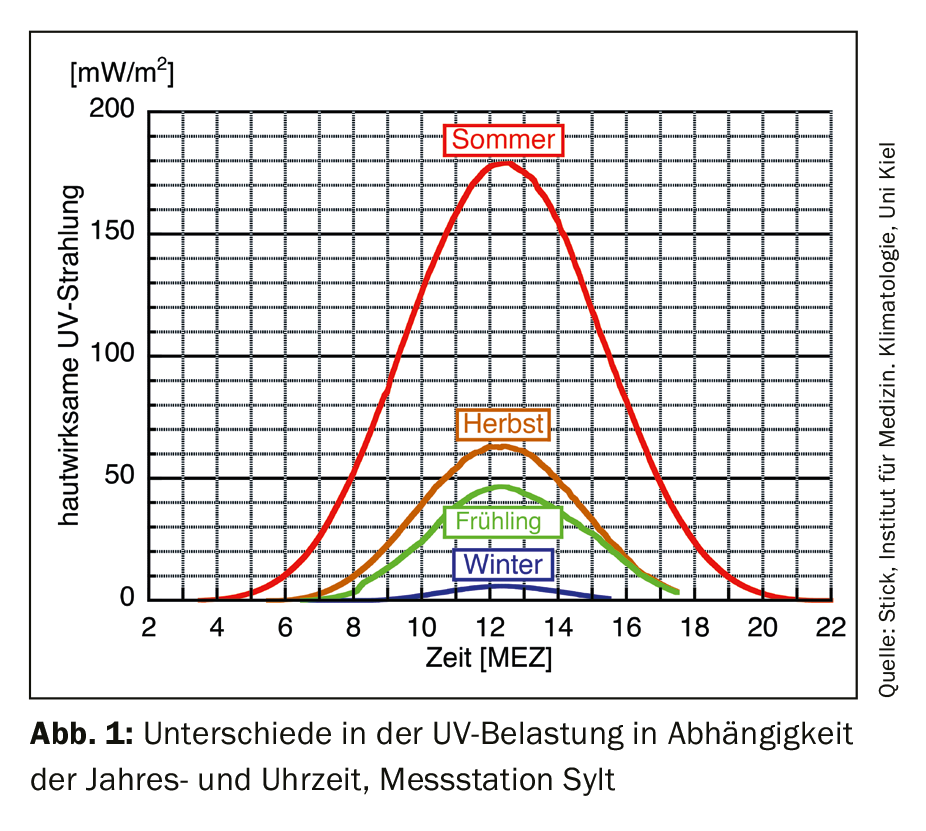

The UV index (UVI) is a seasonal, diurnal, and location-dependent measure of the strength of UV radiation from the sun (radiant power of skin-active radiation per area in watts per square meter), ranges from 1-11+, and is primarily determined by the position of the sun. Furthermore, the ozone layer, weather conditions (clouds), altitude and reflections from water, sand and snow influence the effectively achieved values. The higher the UVI, the faster you get sunburned and the more harmful the UV radiation. The UVI is higher on clear days than on very cloudy ones, significantly higher in summer than in winter, and experiences a steep increase here at midday, which is why the midday sun should be avoided in particular (Fig. 1). From UVI 3, the application of a sunscreen is necessary. With increasing values, the combination with textile light protection such as T-shirt, hat or sunglasses is recommended. From index 8 (midday summer months Switzerland), outdoor exposure should only be done with potent light protection or even avoided completely; dermatitis solaris can develop unprotected from 15 minutes [3].

Protective measures such as physical, chemical and textile light protection

Before any protective measure, the basic avoidance of natural (sun) or also artificial (solarium) UV radiation must be taken. To a certain extent, the skin also has a physiological light protection (melanin, light callus). Sunscreens are divided into physical or chemical sunscreens and textile sunscreens. The sun protection factor (SPF/SF) indicated on European sun creams refers purely to UVB radiation and describes the extension of the exposure time before redness occurs in relation to unprotected skin; an SPF 10 thus extends the exposure time by a factor of 10. The American factor SPF (Sun Protecting Factor) is not equivalent to the European one, here 30% protection factor must be deducted in comparison [4].

In sunscreen with physical light protection, mineral pigments such as titanium oxide, zinc oxide, iron oxide, kaolin, talc are added, which largely reflect and scatter UV light. These often have an opaque white effect that is perceived as annoying, but this is much less pronounced in modern UV filters consisting of nanoparticles. In contrast, chemical UV filters cause absorption of UV light and, based on Stokes’ law, a shift in the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation and thus conversion to heat. Here, substances such as butylmethoxydibenzoylmethane, octocrylene, ethylhexylmethoxycinnamate (EHMC) are mainly used in Switzerland. As a disadvantage, it must be mentioned that they have a potential for developing contact allergies and are suspected of influencing the hormonal system.

Sunscreen application should be done 30 minutes before sun exposure. Apply sunscreens with a high sun protection factor (at least SPF 30, better SPF 50) with UVA and UVB filters generously and renew them after bathing or heavy sweating. Pay special attention when applying cream to sun terraces such as the ear helix, forehead, nose, crown region and shoulders. Adults should wear broad rimmed headgear and sunglasses with UV filters (100% UV protection up to 400 nm) as best as possible. For textile sunscreen, look for quality goods with UPF (Ultraviolet Protection Factor) labeling and choose at least UPF 30. Shade reduces UV exposure by 50% and is therefore also a good additional protective measure. Young children up to the age of one should not be exposed to the sun at all and should play in the shade between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. and be protected by sun hats and glasses.

Patients often make the argument that they need the sun exposure for their vitamin D balance. In this regard, it must be said that vitamin D also has a melanoma-protective effect. However, the unprotected exposure time required for UV-triggered vitamin D production is only about 10-20 minutes daily on the face, hands, and forearms. Not a single study has been able to prove a drop in vitamin D levels due to regular use of sunscreen. This is probably based on the effect that even when SPF 30 is applied, only 97% of UVB rays are filtered out and the remaining 3% are sufficient for vitamin D production. In the winter months, the sun is too weak to trigger sufficient vitamin D, so substitution is generally recommended during this time [5].

Health policy, employee protection and information campaigns

Primary prevention has become indispensable in the field of employee protection. The Swiss Accident Insurance (SUVA) informs on its homepage that 1000 cases of skin cancer illnesses at work are caused by UV radiation per year and especially points out the wearing of a hat with forehead shield and neck protection during outdoor work [6]. The Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SGDV) also emphasizes the need for skin cancer prevention in the workplace by drawing attention on Swiss Derma Day 2018 to the fact that there is a three to five times greater risk when working outdoors [7].

In Austria, one can find the information campaign “Sun without regret” of the Austrian Cancer Aid in cooperation with the Austrian Society of Dermatology and Venereology (ÖGDV), which has now been in existence for more than 30 years, in which the population is widely informed about sun protection, sun damage and skin cancer prevention [8]. In Australia, primary health prevention is written large due to the 40% higher UV exposure and is particularly targeted at children. For many years, UV-resistant full-body protective suits have been worn there for leisure and bathing. Recently, preventive measures have been increasing in schools, so that school uniforms have been developed as long-sleeved versions, 5 kg containers of sunscreen have been placed in schools for free withdrawal by all children, and lunch breaks are spent indoors rather than in the school yard.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention in the context of skin cancer screening is the early detection of skin tumors and their precursors. Tools for this are regular clinical screening and reflected-light microscopy, especially for pigmented skin lesions. However, in clinical examination, it is important to know what to look for, so knowledge of tumor frequencies and distribution as well as clinical and light microscopic signs play a major role.

The clinical and light microscopic screening for white skin cancer

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant skin tumor in humans with a lifetime prevalence of 30%. After the occurrence of a BCC, there is a 30% chance of developing a second basal cell carcinoma within 5 years. Nodular BCC (50%) is the most common presentation, followed by sclerodermiform BCC (25%) and superficial BCC (15%). The most frequent localization is the head area, here especially in the area of the nose, inner corner of the eye, zygomatic bone and forehead, as well as the trunk area.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common skin cancer, occurs twice as often in men as in women, and is most common in the 50-70 age group. They show up to 80% in the head area, especially on the alopecic capillitium, ears and lower lip. On the extremities, they are found on the backs of the hands, finger extensor sides and lower legs.

Actinic keratosis (AK) as a precursor of squamous cell carcinoma is an in-situ SCC and sign of chronic UV-damaged skin with a prevalence of 15% in men and 6% in women in Europe. At the age of 70 years, the incidence of disease increases even to 34% in men and 18% in women [9]. The distribution corresponds to SCC, but more relevant with regard to the therapy alternatives is the degree of expression, which is divided into grade I-III according to Olsen (early, advanced and long-term AK). In grade I, a few rather palpable rough, possibly slightly scaling reddish spots appear. Grade II AK are clearly visible and palpable, flat or slightly raised red keratinized plaques. Older grade III AK present as firmly anchored wart-like lesions with irregularly humped surfaces of varying color (Fig. 2).

Further, the extent is divided into few AK (<5), multiple AK (>6) and field carcinization, and note the type, which can be either erythematous scaling, keratotic to the formation of a cornu cutaneum, pigmented and lichenoid. Even if these grow very slowly, there is an indication for treatment in terms of skin cancer screening for all AK, since about 10-20% of all patients with multiple actinic keratoses develop into SCC in the course.

Thus, regular screening examinations with special attention to the predilection sites are recommended, at least once a year for the first BCC or SCC; at least twice a year from the age of 50, the second white skin cancer or also in the presence of multiple actinic keratoses. Recently, documented associations have emerged between long-term use of hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) at a cumulative dose greater than 50 g and the development of white skin cancer. Thus, for BCC, the risk is increased 1.3-fold, and for squamous cell carcinoma, the risk is increased as much as 4 to 7.7-fold. Therefore, it is recommended to actively approach patients about taking HCT, to include this in screening intervals, and to provide feedback to the primary care physician if necessary.

Diagnosis of AK and white skin cancer is performed clinically, by reflected light microscopy and, if unclear, by sample biopsy. The clinic of BCC depends mainly on the type and location. A pink or brown-skinned shiny nodule or plaque with a waxy or even scar-like appearance is often found. Often there is a non-healing wound or ulceration, pearl cord-like marginal accentuation, and bizzare tree vessels (Fig. 3).

Classic clinical sign of SCC is a red, rough or bumpy nodule or indurated plaque. The nodule is often whitish-horny, sometimes crusty, or ulcerated and bloody as it progresses.

The clinical and reflected light microscopy screening for melanoma.

The most common location for melanoma in both sexes is the back at 24%, followed by the lower legs in women. Only 25% of melanomas arise from preexisting nevi; by far the greater proportion arise de novo in previously inconspicuous skin. Two thirds of advanced melanomas are discovered by the life partner through their clinical conspicuity, which subsequently leads to an evaluation and diagnosis by the dermatologist. Lentigo maligna melanoma is a typical disease of old age with a peak between 60 and 80 years and is mainly localized on the face.

Standard screening intervals are once a year, with dermoscopy being the main screening technique. The strength of the classic hand dermoscope is the assessment of individual nevi in the context of the overall picture (“ugly duckling” phenomenon). However, the disadvantage of this method is that this always represents only a snapshot. Digital reflected light microscopy offers the advantage of direct image comparison over time and thus has the strength in detecting early melanomas. In high-risk patients with, for example, dysplastic nevus syndrome, it therefore makes sense to combine both methods and perform them at 6-month intervals with a time delay.

The dermatoscopic descriptive approach with pattern analysis describes simple algorithms for the assessment of pigmented lesions. If the lesion consists of more than one color or more than one pattern or appears chaotic, the examiner must next perform a test for the presence of malignancy criteria. If these are found, the skin lesion with potential suspicion of melanoma is excised [10].

Regular self-examination by the patient of his skin is another important preventive tool. Here, he is instructed to assess his nevi according to the ABCDE rule (Fig. 4).

A (Asymmetry) stands for an inequality of the pattern in relation to the centerline, B (Border irregularity) for an irregular border, C (Color variation) for different colors such as gray, black, red or white, D (Diameter) for a diameter larger than 5 mm or a size growth and E (Elevation) a thickness growth.

Tertiary Prevention

The final pillar of skin cancer prevention is tertiary prevention, which includes early therapy of skin cancer to prevent progression. Whereas in melanoma the therapeutic approach at each stage is excision and, if necessary, re-excision, in BCC and SCC multiple local therapies, surface procedures or minimally invasive procedures prevent progression of in-situ tumors into invasive carcinomatosis.

The choice of method is made depending on the extent of AK (scattered, multiple, and field carcinization), the degree of AK expression (grade I-III), and the type (erythematous vs. keratotic). For single-cell lesions, cryotherapy using the contact or spray method with liquid nitrogen is the therapy of choice. If necessary, cryotherapy is repeated after 3 months if the response is insufficient. Alternatively, especially in hyperkeratotic grade III lesions, curettage can be performed, alternatively in combination with electrodesiccation of the wound bed, but this may lead to delayed wound healing in older patients, or an ablative laser procedure usingCO2 or erbium YAG laser can be applied.

Isolated lesions or limited infestation can be well treated with ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% once daily for three consecutive days on the face or 0.05% for 2 days on the body. The advantage is the short application time with the disadvantage of a strong and often difficult to control local reaction. In multiple and especially hyperkeratotic AK, local therapy in the combination of 10% salicylic acid with 0.5% fluorouracil once daily for a maximum of 12 weeks is recommended. If multiple AK of varying degrees and types are found, either Imiquimod 5% three times a week for 4 weeks and another cycle for 4 weeks if necessary or 5% Fluorouracil cream twice daily for 3 weeks is recommended. In cases of more severe keratinization and scaling, pre-therapy with urea, salicylic acid or topical retinoids may be helpful. With all local therapies, extensive patient education about the mode of action and expected local reaction is key to success. The patient must know that a violent inflammatory reaction will occur. It is best to support the clarification with visual material and to carry out an inspection in the practice at the time of the most expected reaction.

In case of field canker sores with grade I infestation, large-area local therapy with 3% diclofenac gel twice daily for 12 weeks is recommended, followed by a success check in the office. If the AK are numerous but already advanced and persisting for a long time, photodynamic therapy (PDT) with 5-ALA (5-aminolevulinic acid) or as MAL-PDT (methylaminolevulinate) is the therapy of choice. This is performed either as daylight PDT or conventionally with an irradiation lamp. The advantage of daylight PDT is the easy handling and the low pain development, but the disadvantage here is the poorer controllability of the result by factors such as weather, compliance, etc. In classical indoor PDT with an irradiation lamp, MAL or 5-ALA is applied after conditioning of the treatment area and removal of the hyperkeratoses and protected from light exposure for three hours under an occlusive dressing. This is followed by exposure to intense red light of 37 J/cm². During the educational discussion, it is important to draw the patient’s attention to the sensation of heat and pain during treatment and to the inflammatory reaction (Fig. 5), which is usually maximal on the third post-interventional day, with redness, swelling, pustules, secretion formation, and crusts, and to arrange for a checkup in the office if initial therapy is required. PDT twice a week apart is also, like cryotherapy and curettage with electrodesiccation, a treatment alternative for superficial basal cell carcinoma.

Take-Home Messages

- Only the patient who is informed knows how to protect himself from UV light and to recognize its consequences at an early stage.

- Avoiding the midday sun from 11 am – 1 pm and regularly applied sunscreen are the two most important preventive measures.

- The head, face and back should always be closely examined due to the probability distribution of skin cancer.

- Extensive patient education about the expected inflammatory reaction with all local therapies and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses is essential.

Literature:

- Kunze U, et al: Preventive Medicine, Epidemiology, Social Medicine. Vienna: Facultas, 2004.

- Altmeyer P, Peach V: Encyclopedia of Dermatology, Allergology, Environmental Medicine. Heidelberg: Springer, 2011.

- Federal Office of Public Health, MeteoSwiss: UV protection. www.uv-index.ch/de/uvschutz.html, last accessed 02.05.2019

- Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. Sixth edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, 2016.

- Federal Office of Public Health: Fact sheet – Vitamin D and solar radiation, 08.06.2017. www.bag.admin.ch, last accessed 02.05.2019

- Swiss Accident Insurance. Sun, heat, UV and ozone. www.suva.ch/de-ch/praevention/sachthemen/sonne-hitze-uv-und-ozon, last accessed 02.05.2019

- Mainetti C: Media release Leading Swiss dermatology alarmed: Increasing occupational diseases due to sun, 2018, Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology. https://my.derma.ch/, last accessed 02.05.2019

- Austrian Cancer Aid: Sun without regret 2019. https://sonneohnereue.at, last accessed 02.05.2019

- Stockfleth E, et al: Guideline Actinic Keratosis, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin 2004.

- Kittler H, Tschandl P: Dermatoscopy: Pattern analysis of pigmented and unpigmented skin lesions, 2nd rev. ed. Circulation. Vienna: Facultas, 2015.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(3): 13-18