When treating bone metastases, interdisciplinary discussion is necessary to ensure an optimal multimodal therapy regimen and thus the best possible outcome for the patient. Radiotherapy is considered the treatment of choice for uncomplicated bone metastases. Different therapy regimens are possible. A pathological fracture should first be treated osteosynthetically before irradiation. The early diagnosis (therapy within 24-48 hours after the onset of symptoms) and the radiation sensitivity of the tumor are crucial for the best possible success of therapy in spinal cord compression.

Bone metastases are the most common cause of pain in tumor patients [1]. Besides pain, bone metastases may cause other symptoms such as hypercalcemia, pathologic fractures, and spinal cord compression. The appearance of osseous metastases provides evidence that the tumor disease is in the generalization stage. Thus, the goal of treatment is palliative, regardless of the sometimes very good long-term results with solitary metastases of thyroid or renal cell carcinoma.

Therapy goals and options

Bone metastases are most common in breast, prostate, lung, and renal cell carcinoma [2]. The goals of therapy are pain reduction, function preservation (prevention of fractures and/or myelon compression), function restoration (stabilization of incurred fractures and/or elimination of myelon compression), and prevention of local metastatic recurrence. There are various options for the treatment of bone metastases: conservative therapy with local radiation, systemic (chemo)-therapy, hormone therapy and, if necessary, embolization of tumor vessels, as well as surgical therapy.

Recurrent bone metastases

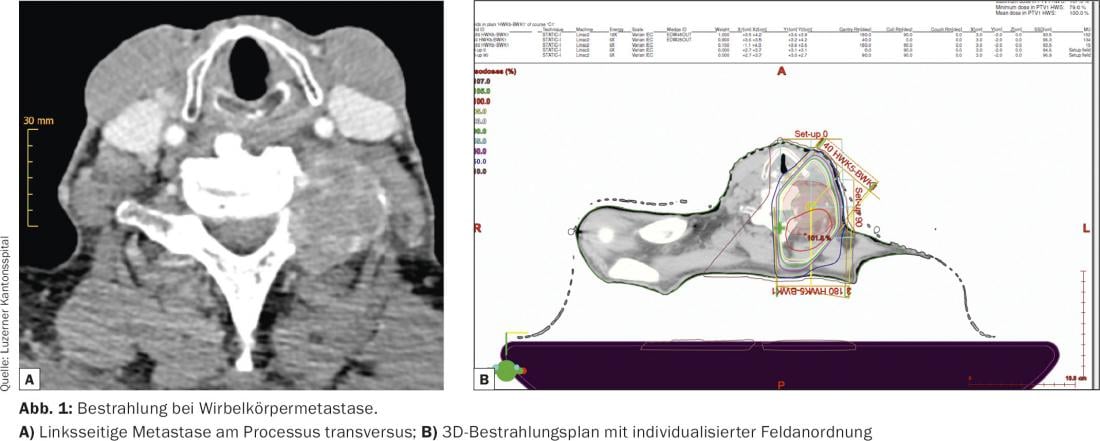

Painful metastases without (impending) fracture or without spinal cord compression in spinal metastases are referred to as uncomplicated bone metastases (Fig. 1) . The available randomized controlled trials show partial or complete pain relief after irradiation after approximately three to eight days in more than 80% of patients. In at least 50% of patients, this pain relief lasts six months or longer, and a good third of irradiated patients become pain-free [3]. An international consensus conference defined standards for partial response of painful bone metastases to radiotherapy [4]. An improvement of two points on a 10-point analog scale without intensification of pain medication and reduction of analgesic requirement by 25% without increase in pain are considered partial response.

Under radiation therapy, there may be a temporary increase in pain. The incidence of this phenomenon, known as a “pain flare,” ranges from 14 to 44% and can be significantly reduced by the prophylactic administration of dexamethasone [5–7]. Studies showed that after administration of 8 mg dexamethasone before irradiation with 1× 8 Gy, a “pain flare” occurred in only 3% of patients [6].

Different irradiation regimes

In randomized trials, the following four radiation regimens were compared in terms of response, complete freedom from pain, re-irradiation for pain recurrence, and pathologic fractures in the subsequent course:

- A single irradiation fraction (single time irradiation).

- Single-time and fractionated short-time irradiation with up to six fractions

- One-time and long-term irradiation (10× 3 Gy in two weeks).

- Fractionated short-term and long-term irradiation

Assuming a single application of 8 Gy, the degree and duration of pain relief in the studies did not correlate significantly with the irradiation regimen used (single dose vs. fractionated administration) [3]. However, the data show a significantly increased rate of subsequent retreatment after single irradiation compared with a fractionated regimen [3]. Reirradiation after a single time irradiation is considered effective, safe and with few side effects [8,9]. Grade 3 acute toxicity on re-irradiation has not been described. Response rates after re-irradiation are similar to those after primary irradiation, with response rates as high as 87% [8,9]. If re-irradiation is required after fractionated irradiation with a higher total dose, the use of special techniques such as high-precision techniques should be considered if necessary to better spare healthy tissues and avoid late radiogenic damage. These techniques can be used in the spine area. Significant pain relief was achieved in 81-100% of cases [10–13].

Pathological fractures after radiotherapy

Regarding the rate of pathologic fractures after radiotherapy, there was no significant difference between single-time and fractionated irradiation in the recent studies and meta-analyses. One study showed a more significant increase in bone density after 10× 3 Gy than after 1× 8 Gy [14]. With regard to fracture rate, the absolute difference between different regimens decreased with the use of bisphosphonates. In randomized trials, bisphosphonates resulted in a significant reduction in “skeletal related events” including fractures [15–17].

Complicated bone metastases

We speak of complicated bone metastases when, in addition to pain symptoms, serious complications such as a pathological fracture or metastatic spinal cord compression are present. A pathological fracture should first be treated osteosynthetically (Fig. 2) . Since surgery does not result in complete destruction of the tumor tissue, postoperative radiotherapy is required to prevent recurrence and loosening and dislocation of the osteosynthetic material.

In addition to pain relief, the main goal of postoperative irradiation is to remineralize the fractured bone (Fig. 3). After one-time irradiation, remineralization is usually insufficient [14]. Therefore, in case of pathological fracture, a long-term regime should be performed (mostly 10× 3 Gy in two weeks) [14,18]. However, relevant remineralization is not expected until months after radiotherapy. Therefore, single-treatment irradiation may be considered in patients with limited survival prognosis.

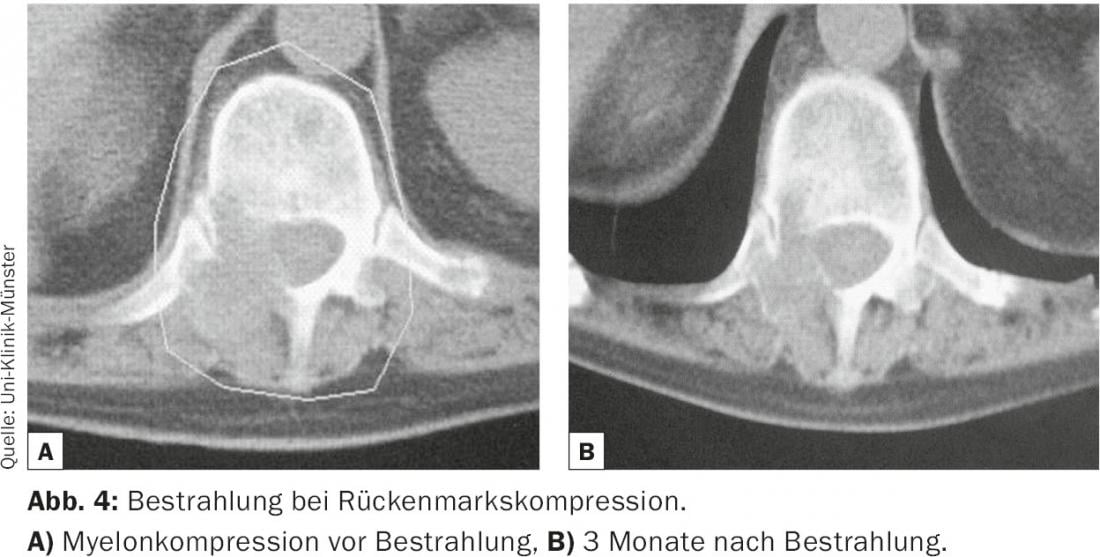

Radiotherapy for spinal cord compression

For radiotherapy of metastatic spinal cord compression, single-time irradiation with 1× 8 Gy, fractionated short-term irradiation with 5× 4 Gy, and long-term regimens such as 10× 3 Gy, 15× 2 Gy, or 20 x 2 Gy are comparable in terms of their effect on motor function (Fig. 4) [19]. Response rates in terms of improvement in motor function or prevention of neurological progression are approximately 85%. However, recurrence within the irradiation field is significantly more frequent after single-time or fractionated short-term irradiation than after irradiation with a long-term regime [20,21]. Thus, patients with better survival prognosis should receive long-term irradiation with, for example, 10× 3 Gy.

The early diagnosis (therapy within 24-48 hours after the onset of symptoms) and the radiation sensitivity of the tumor are decisive for the best possible success of the therapy. Initial intervention consists of intravenous application of high-dose steroids [22] In any case, a neurosurgeon should be consulted, because surgical interventions such as laminectomy can rapidly induce the effect of decompression. The same applies to vertebral body fractures: For any stabilization surgery, the patient should be presented to the neurosurgeon. The indication for surgery is based on certain inclusion and exclusion criteria. Again, surgery does not replace radiotherapy (after wound healing is complete).

The premise is to initiate therapy as quickly as possible: Here, the possibility of direct simulation of the irradiation field and therapy by means of ap/pa field arrangement is offered, so that sufficient tumor therapy is guaranteed without loss of time. In the case of re-irradiations or tumor localizations that make it essential to spare healthy tissue, a three-dimensional irradiation plan is drawn up on the basis of the planning CT; irradiation is performed according to individual field arrangement with optimal dose delivery to the tumor and the best possible sparing of healthy tissue.

To gain time in an emergency (e.g. acute paraplegia), therapy can be started with ap/pa field arrangement and continued with 3D plan. Dexamethasone therapy is also continued during radiotherapy to prevent radiogene-induced tissue swelling and associated compression symptoms.

Conclusion

When treating bone metastases, interdisciplinary discussion is necessary to ensure an optimal multimodal therapy regimen and thus the best possible outcome for the patient. Radiotherapy is considered the treatment of choice for uncomplicated bone metastases: various fractionation schemes can be used, pain control is very good with a low rate of side effects, re-treatment can be performed at the same site, and even in the spine, reirradiation is possible with the use of special techniques at best.

Literature:

- Mercadente S: Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain 1997; 69: 1-18.

- Modaressi K, et al: Bone metastases – workup and therapy; Schweiz Med Forum 2013; 13(29-30); 571-579.

- S3 guideline prostate cancer; version 2.0; 1st update 09/2011.

- Chow E, Wu JS, Hoskin P, et al: International consensus on palliative radiotherapy endpoints for future clinical trials in bone metastases. Radiother Oncol 2002; 64: 275-280.

- Chow E, Ling A, Davis L, et al: Pain flare following external beam radiotherapy and meaningful change in pain scores in the treatment of bone metastases. Radiother Oncol 2005; 75 :64-69.

- Chow E, Loblaw A, Harris K, et al: Dexamethasone for the prophylaxis of radiation-induced pain flare after palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases – a pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2008; 15 :643-647.

- Foro Arnalot P, Fontanals AV, Galceran JC, et al: Randomized clinical trial with two palliative radiotherapy regimens in painful bone metastases: 30 Gy in 10 fractions compared with 8 Gy in single fraction. Radiother Oncol 2008; 89: 150-155.

- Katagiri H, Takahashi M, Wakai K, et al: Prognostic factors and a scoring system for patients with skeletal metastasis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87: 698-703.

- Mithal N, Needham P, Hoskin P: Retreatment with radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1994; 29: 1011-1014.

- Gerszten PC, Burton SA, Ozhasoglu C, et al. Radiosurgery for spinal metastases: clinical experience in 500 cases from a single institution. Spine 2007; 32: 193-199.

- Milker-Zabel S, Zabel A, Thilmann C, et al: Clinical results of retreatment of vertebral bone metastases by stereotactic conformal radiotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 55: 162-167.

- Nielsen OS, Bentzen SM, Sandberg E, et al: Randomized trial of single dose versus fractionated palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases. Radiother Oncol 1998; 47: 233-40.

- Ryu S, Fang Yin F, Rock J, et al: Image-guided and intensity-modulated radiosurgery for patients with spinal metastasis. Cancer 2003; 97: 2013-2018.

- Koswig S, Budach V: Remineralization and pain relief in bone metastases after different radiotherapy fractions (10 times 3 Gy vs. 1 time 8 Gy). A prospective study. Radiation Oncol 1999; 175: 500-508.

- Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Igrutinovic I: Single 4 Gy re-irradiation for painful bone metastases following single fraction radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 1999; 52: 123-127.

- Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, et al: Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: a phase II, double-blind, randomized trial – The Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3150-3157.

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al: Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96: 879-882.

- Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR: The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases. Final results of the study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer 1982; 50: 893-899.

- Rades D, Stalpers LJ, Veninga T, et al: Evaluation of five radiation schedules and prognostic factors for metastatic spinal cord compression. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 3366-3375.

- Rades D, Fehlauer F, Schulte R, et al: Prognostic factors for local control and survival after radiotherapy of metastatic spinal cord compression. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 3388-3393.

- Rades D, Lange M, Veninga T, et al: Final results of a study comparing the local control of short-course and long-course radiotherapy for metastatic spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011; 79: 524-530.

- Souchon R, et al: DEGRO practice guidelines for palliative radiotherapy of metastatic breast cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 2009; 185; 417-424.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(3-4): 10-13.