Drug safety is about research before and after approval of a drug, knowledge of physicians and special patient groups, but also about integration of technology into everyday hospital life. Medication errors and dangerous interactions can thus be avoided.

First, let’s talk about drugs. The “life phases” of the clinical development of a drug are sufficiently well known. Beginning with premarketing, which includes Phase I through III trials, through to submission to the appropriate drug regulatory agency (e.g., the FDA in the U.S.) and approval – assuming the drug survives testing. While in recent years special study populations, i.e. persons of older age, with renal/liver diseases, of different ancestry, etc., have increasingly been included in the premarketing phase, this obviously does not cover all treatment groups and situations by far. For example, pregnant women and children are often excluded for ethical reasons.

Therefore, to better assess the safety of a drug, postmarketing (Phase IV) follows approval, where long-term surveillance of adverse events, systematic monitoring, and pharmacoepidemiological safety studies are conducted. Since the end of the 1990s, this “life phase” of the drugs has been increasingly systematized and more actively integrated into the overall marketing concept. Today, it is usually already proactively considered or integrated in the development of new substances (i.e., systematic, population-based, epidemiological safety studies are usually negotiated at the same time as a marketing authorization is submitted).

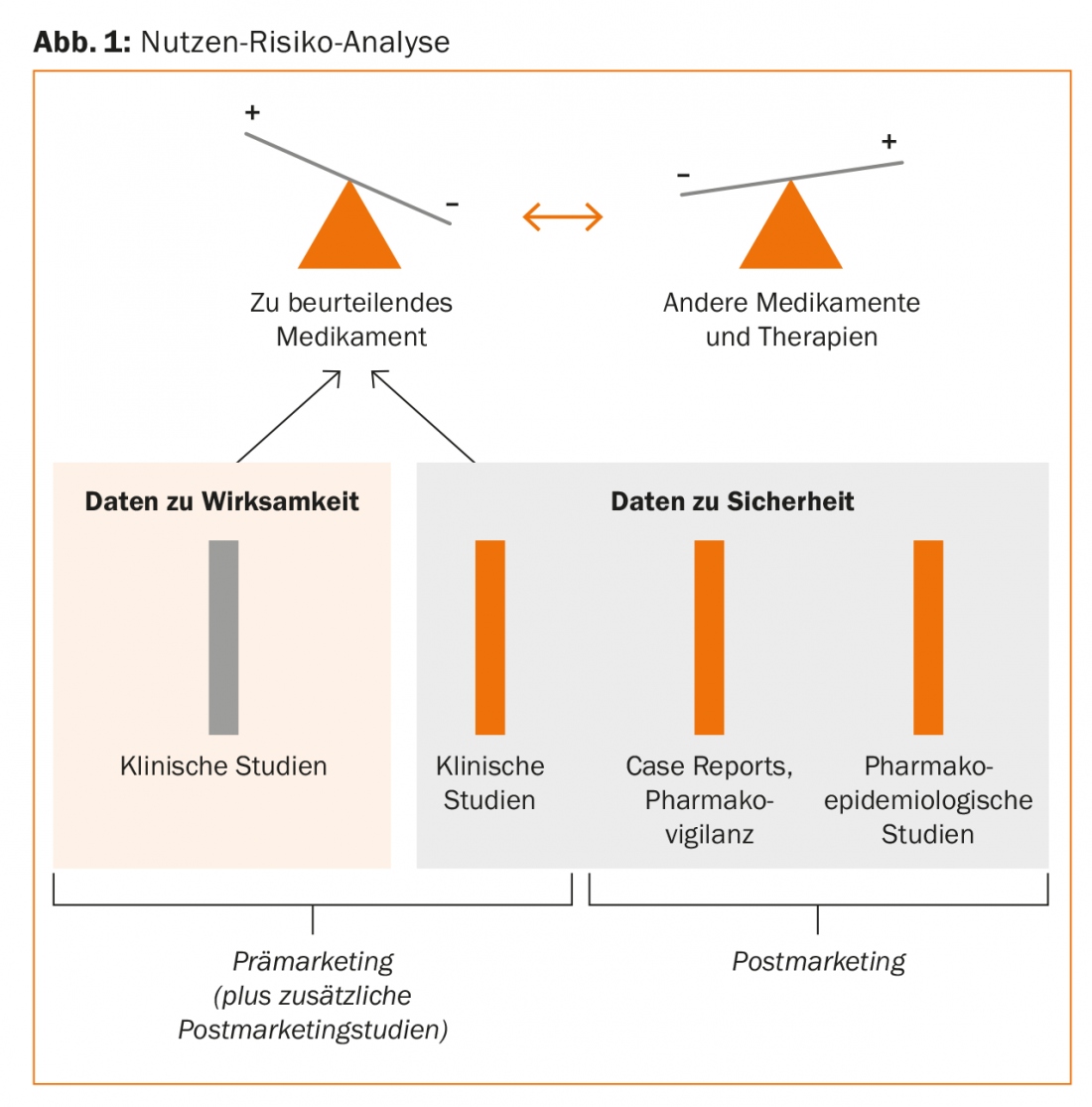

A rational benefit-risk analysis of drugs with the same indication thus rests on the following pillars:

- Clinical studies (Phase I, II, III)

- Case Reports/Pharmacovigilance (Spontaneous Observations).

- Pharmacoepidemiologic studies (Fig. 1).

The area of pharmacovigilance or case reports can be qualitatively evaluated very well and has a signal effect (hypothesis generation), but is poorly suited for the quantification of relative risks. The largest body of evidence comes from systematic pharmacoepidemiologic studies. “This area is now highly specialized and the studies are very extensive and demanding. What we can do very well with the new technical possibilities in everyday life, however, are evaluations based on clinical information systems. We published corresponding studies on drug interactions in 2011 [1]. Our data on second-generation neuroleptics from 2016 [2] also show that this is also possible locally, at your own hospital, and that it makes sense to improve the safety of prescriptions,” the speaker explained.

Life phases of physicians

With regard to medication errors, Ashcroft et al. two years ago nicely demonstrate that young, inexperienced physicians make twice as many errors in the first and second year as older physicians, but that the latter by no means “get away” without medication errors and that the errors – if they make any – are just as serious. This means that interventions are indicated not only for junior physicians but also for senior physicians to avoid potentially serious medication errors [3]. The willingness to continue learning and learning throughout life (including older from younger), as well as the integration of modern technology (e.g. iPad on rounds) into decision-making are prerequisites for this.

“Do we actually adhere to the Hippocratic principle ‘Primum non nocere’ (or in German: First do no harm)? Here’s an example: For an otherwise fatal disease, do you prescribe drug 1, which cures 75% of patients but carries a risk of an acute fatal side effect of 1:10,000 cases, or drug 2, with a cure rate of 80% and a corresponding risk of 1:100?”, Prof. Russmann asked the audience. “Quite a few would choose drug 1. However, this causes 421 more deaths than drug 2.” The corresponding calculation is very simple:

Drug 1: One patient in 10,000 dies, of the remaining 9999, 7499 are cured. Thus, 7499 out of 10,000 survive.

Drug 2: 100 patients out of 10,000 die, of the remaining 9900, 7920 are cured. 7920 out of 10,000 survive.

Defensive decision making, i.e. a self-protective attitude on the part of the physician, combined with an incorrect intuitive assessment of probabilities, can thus be dangerous for the patient. To stay with the above example: The fact that the patient died from the disease instead of from the medication prescribed by his own hand is somewhat easier for the physician to bear.

A summary of how to improve medication safety on the physician side is shown at 1.

Life phases of evidence

The following principles are relevant here:

- Use drugs with a well-documented safety profile

- Staying “up to date”, continuing your education

- Remain critical of new evidence, examine carefully

- Concerns: “Whenever a new drug comes on the market something crazy will happen”.

Life phases of hospitals

With systematic analyses and clinical information systems, dangerous or even contraindicated drug combinations can be identified and indicated in time. Interaction checks are possible via www.mediq.ch, for example. Prof. Russmann, as a clinical pharmacologist and epidemiologist, is himself intensively involved in this topic and has co-developed and implemented the so-called “interventional pharmacoepidemiology” program. In this process, a large number of prescriptions are registered via an electronic hospital information system and a local pharmacoepidemiological hospital database is established. Through the “interventional pharmacoepidemiology” program, medication errors in hospitals can be identified, quantified and their clinical relevance evaluated within a very short time. This allows targeted automated alerts to be integrated into electronic drug prescribing (in “real time”). In addition, cohort/case-control and longitudinal studies with information on prescribing patterns, side effects, and economic aspects are obtained from the data. Two publications in recent years show that this works [4,5].

Proactive quality management, as well as investments in IT and the above-mentioned systems that identify potential pharmacotherapy problems, assess clinical relevance and provide timely warnings of critical situations, are thus central. In addition to stability in the workforce and low staff turnover, they help a hospital to improve medication safety sustainably and in the long term.

Life stages of patients

Finally, a few words about patients late in life.” In the elderly, due to multimorbidity and thus polypharmacy, the examination of interactions between drugs (“drug-drug-interaction”) is central. However, interactions between drugs and diseases (“drug-disease-interaction”) must not be forgotten. An inventory of renal function and any dose adjustments, regular clinical visits and progress monitoring of various parameters such as blood pressure, ECG, etc. are also components of a clinical practice aimed at improving drug safety. “For the pediatric population, patients at the beginning of their life span, the website/knowledge base kinderdosierungen.ch provides valuable information,” he said.

Source: 15th Annual Meeting of the SGAMSP, September 28, 2017, Wil

Literature:

- Haueis P, et al: Evaluation of drug interactions in a large sample of psychiatric inpatients: a data interface for mass analysis with clinical decision support software. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011 Oct; 90(4): 588-596.

- Low DF, et al: Second-generation antipsychotics in a tertiary care hospital: prescribing patterns, metabolic profiles, and drug interactions. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2016 Jan; 31(1): 42-50.

- Ashcroft DM, et al: Prevalence, Nature, Severity and Risk Factors for Prescribing Errors in Hospital Inpatients: Prospective Study in 20 UK Hospitals. Drug Saf 2015 Sep; 38(9): 833-843.

- Low D, et al: Development, implementation and outcome analysis of semi-automated alerts for metformin dose adjustment in hospitalized patients with renal impairment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016 Oct; 25(10): 1204-1209.

- Low D, et al: Paracetamol overdosing in a tertiary care hospital: implementation and outcome analysis of a preventive alert program. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2016; 41(5): 515-518.

Further reading:

- Gigerenzer G: Risk: How to make the right decisions. Munich: Random House GmbH 2013.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(6): 39-41.