Pain management is one of the great challenges in palliative care, but often one with measurable therapeutic success. In advanced stages, all pain management options should be exhausted to improve quality of life. If therapy fails, it is necessary to contact a pain specialist. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced tumor disease can be treated with minimal pain in this way.

Almost all patients who are affected by a serious, often malignant disease, fear pain that cannot be treated. Many of them are familiar with situations of family members or friends who suffered from inadequately treated pain during the course of their illness and had to experience the end-of-life phase in agony. With today’s pain management options, these courses should no longer occur. However, there are situations in which the treatment of pain can reach its limits due to its complexity.

The treatment of the symptom pain is very suitable as an example of good symptom control in palliative care, especially since pain is a frequent problem in the course of life-threatening diseases. Efficient analgesia is one of the main tasks of palliative care. Often, due to the destructive course of the disease, we find a progressive pain situation that requires continuous adjustment of therapy. It is important for the treatment concept to analyze the type of pain and the possible underlying etiologic pathologies in order to apply causal therapeutic approaches, such as pain radiation, whenever possible. Due to inactivity, there is often an increase in pain and therapy can be complicated by increasing organ dysfunction. Especially in the late course of the disease, non-somatic factors for the pain experience are increasingly in the foreground. On the other hand, understandably, symptom control is rarely demanded by patients as vehemently as being free of pain.

Pain Basics

The definition of pain in use today comes from the International Association for the Control of Pain (IASP) in 1986 and reads: Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that is accompanied by real or impending tissue damage – or is described in terms of such damage – often accompanied by vegetative manifestations such as pallor, sweating, and elevation of blood pressure.

Acute pain usually has a useful warning function and is meaningful, protective, and life-sustaining. However, in the case of chronic pain in the course of a malignant disease, pain has lost this useful warning function. Pain can be classified according to its temporal course into acute or chronic, but also according to its pathogenesis into nociceptive, neuropathic and mixed pain, in addition we know the so-called somatoform pain disorder. In the palliative situation, we are usually dealing with chronic progressive, often mixed pain situations, however, acute pain occurs again in the course of the disease, which must be subjected to a differentiated evaluation in order not to miss causal therapy options.

Pain Pathogenesis

The differentiated pain analysis with regard to pathogenesis is indispensable, since a meaningful pain therapy is only possible after a successful classification. We distinguish nociceptive pain from neuropathic pain. Nociceptive pain is pain that usually results from local damage at the site of the lesion. An exception to this is visceral pain, which can make local assignment difficult via Head’s zones.

A good example of a nociceptive event is pain caused by the appearance of bone metastases. In this case, local destruction by irritation of the appropriate receptors triggers a constant baseline pain that is occasionally accentuated by a more intense pain attack.

In contrast, neuropathic pain originates in the central or peripheral nervous system. The onset of pain is often not in immediate temporal relation with some latency of days or weeks after the actual lesion, the pain attacks are frequent and very intense, unpredictable and described as burning, cutting, electrifying and pulsating. In addition, hyperalgesia or hypalgesia, as well as allodynia, may occur. Examples of neuropathic pain include postherpetic neuralgia, phantom limb pain, radicular pain, or centrally triggered pain (thalamic pain).

Cancer pain

In the context of tumor disease, pain can occur that is directly triggered by the tumor, whether by destructive growth in the tissue, pressure or infiltration of nerves, stretching or pressure on hollow organs. Indirect tumor pain results from perilesional edematous inflammation, pathologic fractures, or displacement of hollow organs. Finally, pain also arises as a consequence of tumor therapies postoperatively, postactinically or due to inflammation and consequences of chemotherapy. Whenever possible, after clarifying the cause of the pain, priority is given to the causal therapy option if the associated burden appears justifiable in the overall context. Unfortunately, these options are limited, so symptomatic therapy is often the only option.

Pain therapy

At about the same time that pain was being defined by the IASP, the WHO was developing a staging scheme for the treatment of pain in cancer patients. The goal of this regimen was to alleviate or eliminate pain and prevent recurrence of pain exacerbation. The classification allows for efficient, relatively low-risk and fast-acting pain treatment. Nowadays, the WHO staging scheme, modified, is also used in the treatment of non-malignant pain.

At level 1, the three levels include the classic nociceptive non-opioid analgesics with which we are all well familiar. Examples include paracetamol, metamizole, aspirin, diclofenac, mefenamine, etc. In addition to their analgesic effect, these substances also have antiphlogistic and antipyretic properties to varying degrees. With the exception of paracetamol, they act exclusively peripherally on the nociceptor. Only paracetamol also has a central effect component. In Stage 2 we find the weak opioids. Representatives of this category are tramadol, codeine, dihydrocodeine or tilidine. They have a favorable risk-benefit ratio, have about 1/6-1/10 the efficacy of the reference substance morphine (hence called weak opioids), and are easy to dose. Problems arise in 10% of patients who cannot metabolize codeine, for example, and suffer only from opioid-induced side effects, and from the different metabolizers in whom tramadol leads only to serotoninergic and antiadrenergic orthostasis symptoms.

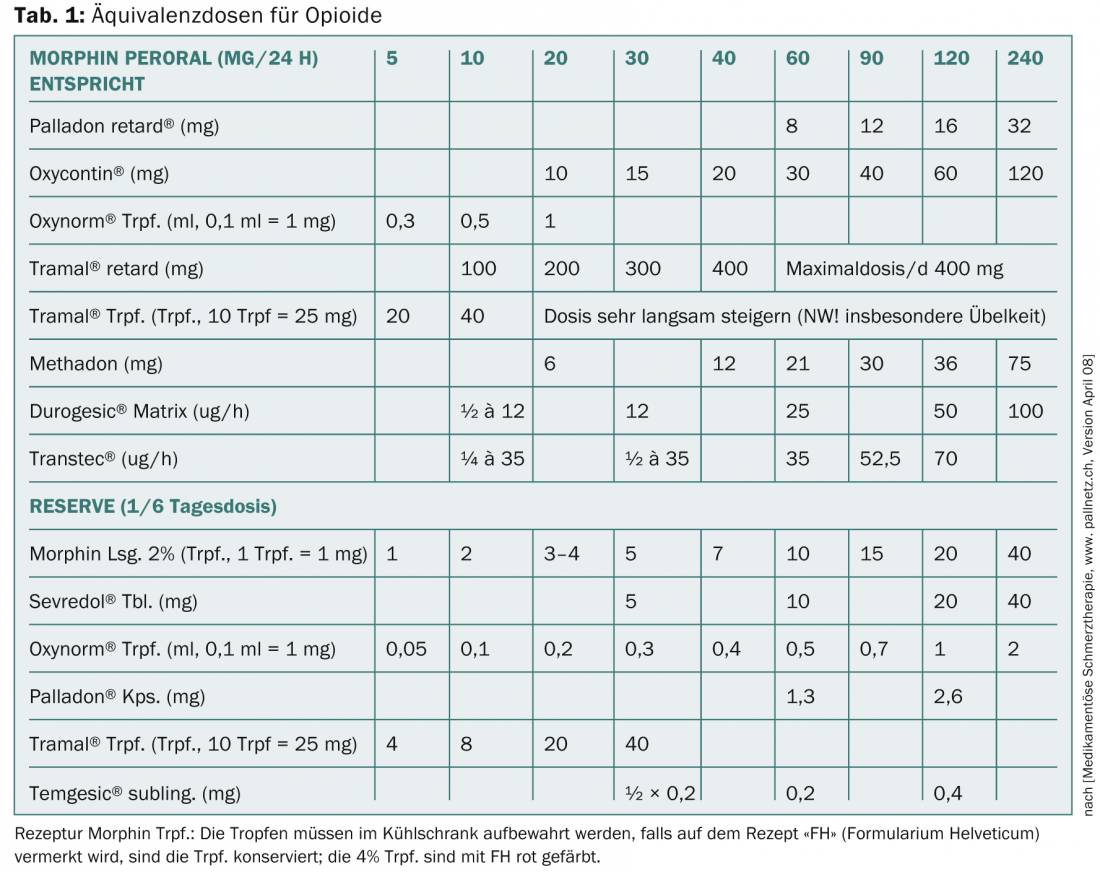

Level 3 includes the classic opioids with the reference substance morphine (more mg for same analgesia – weak opioids; less mg for same analgesia – strong opioids). A summary of equivalent doses for opioids is shown in Table 1 . Opioids inhibit transmission at synapses of the nociceptive system, activate inhibitory systems in the CNS and spinal cord, alter pain sensation by their attack on the thalamus, the limbic system, and thereby also cause anxiolysis. Peripherally at the nociceptor, opioids act mainly in inflamed tissue.

The main problems are opioid-induced nausea, which is usually passive, and permanent constipation, which requires obligatory concomitant medication. The individual substances differ primarily in their different effects on the mü, kappa and delta receptors.

The basic principles of pain management are based on oral administration (by the mouth) with the choice of appropriate galenics, at a fixed time (by the clock) in the sense of prophylactic administration rather than reactive, preferably in sustained release form, and with a stepwise build-up of therapy (by the ladder). A few years later, the individualization of therapy regimens and the consideration of patient needs with regard to non-pharmacological measures were added. The original recommendation of building up over all three stages is no longer followed today, especially in the case of tumor pain and the likelihood of a rapid increase in pain, in order to counteract chronification of pain through unnecessary loss of time.

In principle, stage 1 preparations can be well combined with those of stage 2 or 3, in that the nociceptive therapeutic effect of stage 1 drugs can lead to a sparing effect of opioids. The combination of stage 1 drugs with each other is controversial; there is evidence of synergy for the use of paracetamol and metamizole together. It is not advisable to combine stage 2 and 3 opioids, as competition for the receptor may result in the weaker substance taking effect.

Opioids

Opioids are central medications in palliative care and are often essential for successful symptom control. Therefore, it is worthwhile to take a closer look at some aspects of treatment with these substances.

There are still many myths surrounding opioid administration – not only among patients, but also among physicians. Often, the use of morphine is equated with the beginning of the end because the substance is seen as an iron reserve for dying. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss with the patient the indication for opioid administration, which is clearly justifiable in the symptom control of mainly pain or even shortness of breath. By explaining in detail the mode of action and the goals of the therapy, even rather skeptical patients can be motivated to undergo treatment. This includes information that with a stable opioid dose, for example via a transdermal system, even driving is not prohibited – unless there are other impediments due to the disease.

Dependence: The second fear deals with dependence. Of course, physical dependence develops under opioid treatment, which means that if causal therapy decreases the need for pain medication, an opioid preparation must be slowly phased out, otherwise the classic physical withdrawal symptoms will occur. Psychological dependence does not usually develop, especially when therapy is with sustained-release preparations or transdermal application. An exception is pethidine, here dependence is described, especially when the substance is given intravenously. Therefore, it is recommended to refrain from the administration of this substance. In some cases, a certain habituation occurs in the sense of tachyphylaxis. In terms of differential diagnosis, tumor progression must always be considered in the event of a loss of efficacy, and the possibility of causal pain control must be re-evaluated, even in the palliative setting.

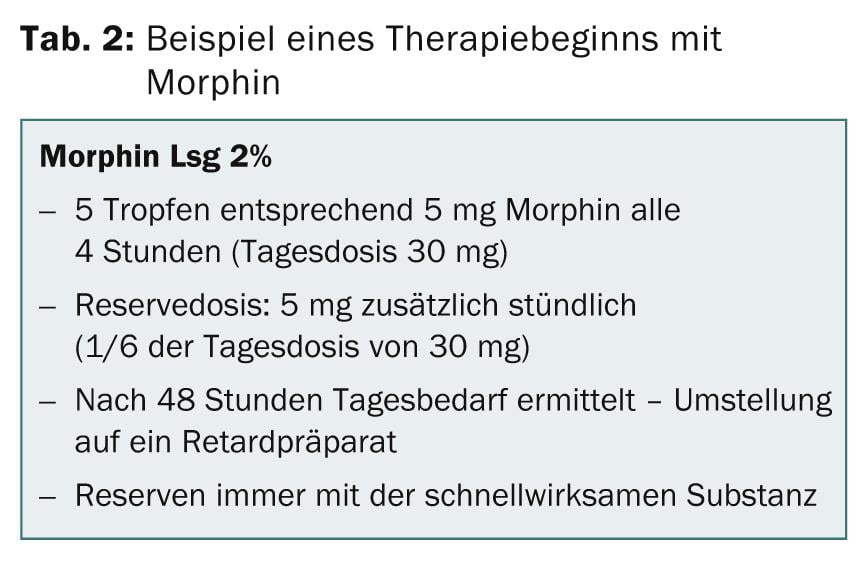

Dosage and side effects: Physicians who are untrained in handling the sometimes high doses of opioids fear the risk of respiratory depression in particular. When used properly, this risk does not exist, since the effect of morphine can be very well assessed clinically. An example start of therapy with morphine can be seen in Table 2.

In the titration phase, the undesirable side effects occur first, i.e., patients complain of nausea and constipation without any analgesic effect. This is often the moment when therapy is discontinued due to intolerance and ineffectiveness. After dose increase, more or less pronounced sedation occurs before analgesia sets in. This analgesic effective dose is referred to as the “therapeutic window” and is the target dose. Unfortunately, the therapeutic window is not always equally wide open, so that once a dose has been determined, it must always be corrected upward or downward. Before the critical dose in terms of respiratory depression is reached, confusional states and neurological symptoms, especially muscle twitching, occur, so that if these symptoms occur, the dose must be reduced.

The choice of opioid in terms of its elimination, renal or hepatic, also plays a role. In this case, possible organ complications should also be taken into account in the choice of preparation. Oxycodone and hydromorphone are often superior to other opioids in this regard. In principle, there is no upper limiting maximum dose for most opioids, but pain control determines the quantity. Particularly with partial agonists, however, a ceiling effect can occur, i.e., a further increase in dose does not cause an increase in effect. Then a rotation to another substance is recommended. Dry mouth, urinary retention, constipation, and orthostasis should not be dose-limiting.

Concomitant medication: The question of concomitant medication is often controversial. We always start antiemetic treatment with metoclopramide, the most potent substance for opioid-induced nausea, in addition to the opioid. It is possible that some of the patients are overtreated with this. However, for those patients who experience this unpleasant symptom, there is often such an aversion to opioids that retrying often requires a long lead time during which pain is endured rather than adequately treated. Usually, the nausea is only passive and the concomitant medication can be stopped after a few days. However, in some cases it persists, so the antiemetic must be maintained. Sometimes opioid rotation, i.e., switching to a different substance, is also needed to control this side effect.

Unfortunately permanent is the disturbing constipation, which usually requires a permanent therapy with laxatives, possibly with more than one preparation. In this case, the combination preparation Oxycontin with naloxone can partially facilitate therapy.

In summary, it must be stated that in a progressive pain situation, the use of opioids often cannot be avoided and that a combination of level 1 analgesics with analgesic comedic drugs is not an alternative for the necessary opioid treatment. Morphine allergy is very rare. Under no circumstances should itching, which is an effect of opioids by irritating the appropriate receptors, be misinterpreted as allergy. As stated above, the occurrence of nausea is not an allergy.

A good knowledge of the substances used is important for successful therapy. The duration of action, onset of action, any ceiling effect, interactions and side effects must be known. Sometimes the side effect can be used for therapy, e.g. diarrhea. A correct hospital or home prescription includes the unit dose, maximum daily dose, preparation, schedule, and reserve dose for breakthrough pain, which is usually 1⁄6-1⁄10 of the daily dose and can be delivered up to hourly, depending on the situation. The goal is low pain with a pain intensity on the VA scale of less than four; if there are more than five reserve doses per day, an increase in the base medication is indicated.

Depending on the character of the pain, the addition of co-analgesics makes sense, for example, the use of antiepileptics or antidepressants in neuropathic pain components. If edema is considered to be a contributing factor, the administration of glucocorticoids should be considered, and neuroleptics or muscle relaxants are also used. However, the use of these preparations is partly limited by the intensification of the already existing Cancer-related-Fatigue.

Reasons for failure of analgesic therapy may include incorrect pain diagnosis or underestimation of pain intensity, inadequate treatment of concomitant symptoms (e.g., anxiety or depression), incorrect dose, too long intervals, or avoidance of potent medications. However, even with lege-artis pain treatment, there are treatment failures that justify the involvement of anesthesiologists experienced in pain management. Invasive procedures may have to be used here.

Always, as a top priority, must be Dame Cicley Saunders’ statement, “Pain is, what the patient says it is.”

Christel Nigg, MD

Nic Zerkiebel, MD

Literature:

- Neuenschwander H, et al: Palliative Medicine, Krebsliga Schweiz, 2nd revised edition, 2006.

- Beubler E: Kompendium der medikamentösen Schmerztherapie, 4th revised edition, Springer WienNew York, 2008.

- Gallacchi G, et al: Schmerzkompendium, 2nd edition, Thieme-Verlag, 2005.

- Recommendations Breakthrough Pain, ed: Swiss Society for Palliative Medicine, Care and Support, palliative ch palliative.ch 2006.

- Eychmüller St: Sense makes sense, Therapeutische Umschau 2012; 69(2): 87-90.

- Büche D.: Assessment and assessment instrument in palliative care, Therapeutische Umschau 2012; 69(2): 81-86.

- National Strategy for Palliative Care 2010-2012, Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) 2009. www.admin.ch/palliativecare

- Indication criteria for specialized palliative care www.bundespublikationen.admin.ch

- Antonovsky A: Salutogenesis. On demystifying health. German edition by Alexa Franke. dgvt-Verlag, Tübingen 1997.

- Hydration at the end of life, Bigorio recommendations: Ed: Swiss Society for Palliative Medicine, Care and Support, palliative ch, 2011.

- Kunz R: Palliative care a comprehensive approach to care, not a new specialty, Swiss Medical Journal, 2006 (87): 1106.

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences SAMS: Palliative Care. Medical ethical guidelines and recommendations, 2006.

- Bruera E, et al: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J of Palliative Care 1991 (7): 6-9.

- Saunders C: Cicley Saunders Dying and living: spirituality in palliative care. Translated from Engl. by Martina Holder-Franz.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(3): 10-14.