What are the signs of problematic alcohol consumption? How can a therapeutic process be initiated? What role does the environment play? Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Monika Ridinger showed the possibilities and limits of GP support in the treatment of alcohol dependence.

There are 250,000 to 300,000 alcohol-dependent people in Switzerland [1]. At risk are constantly 3-5% of the population. The non-representative online Global Drug Survey shows alcohol at the top of the addiction statistics, but cannabis is on the rise [2]. In recent years (2014-2016), alcohol consumption has declined somewhat.

The definition of problematic alcohol use is not always clear-cut in practice, Ridinger said. In psychiatry, one has to deal with a small proportion of those affected, namely just 6% of the really severely affected. People with problematic consumption often do not appear conspicuous at all. In order to be able to narrow down alcohol consumption and its physical and psychological consequences, repeated contact offers in the form of questions are recommended: What motivates patients to consume alcohol? What motivates to change the habits? What could support this?

Alcohol activates the reward system and is often perceived as a pleasure. It’s not as easy to get into the conversation that indulgence may have tipped over and a harmful, problematic habitual use has developed, Ridinger explained. Simple quantifying questions are a good place to start: “Have you consumed alcohol more than 15 times in the last month?” This specification to the last 30 days is important, as is concreteness. To nonspecific questions, “How often have you drunk alcohol recently?” one would typically get only a general response, “Quite a bit.” Quantifications can be used to narrow it down further: “Have you consumed alcohol more than three times a week?”

The measurability of problematic alcohol consumption

For the purpose of determining problematic use, the definition of a specific number of grams is ambiguous. It is necessary to speak of addiction when there have been changes in life due to regular consumption or when the body shows signs. WHO has outlined effects of problematic alcohol consumption [3]. For men, the quantitative limit today is 40-60 g of pure alcohol daily, and for women 20 g (1 dl of wine contains about 10 g of alcohol).

What is treated?

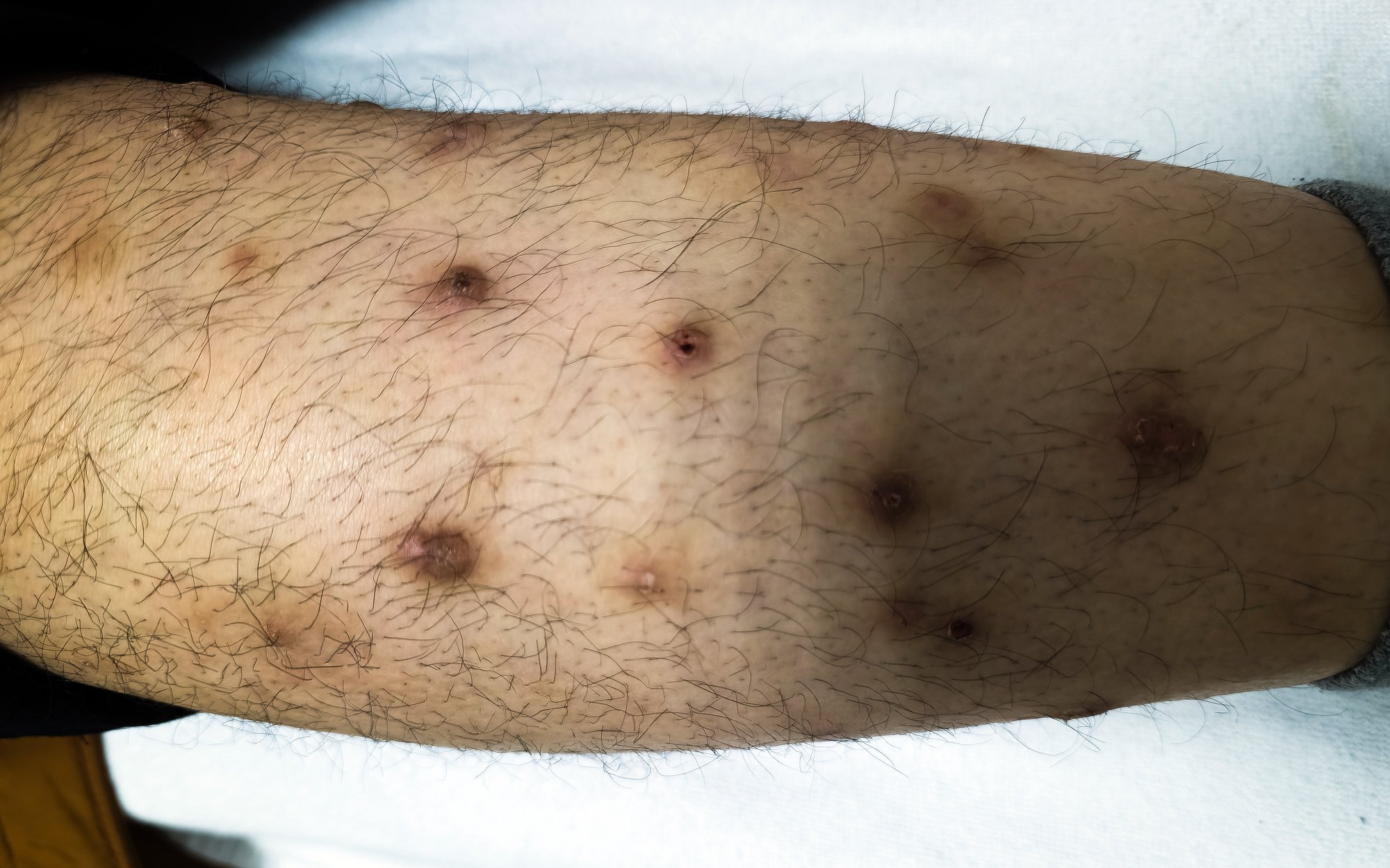

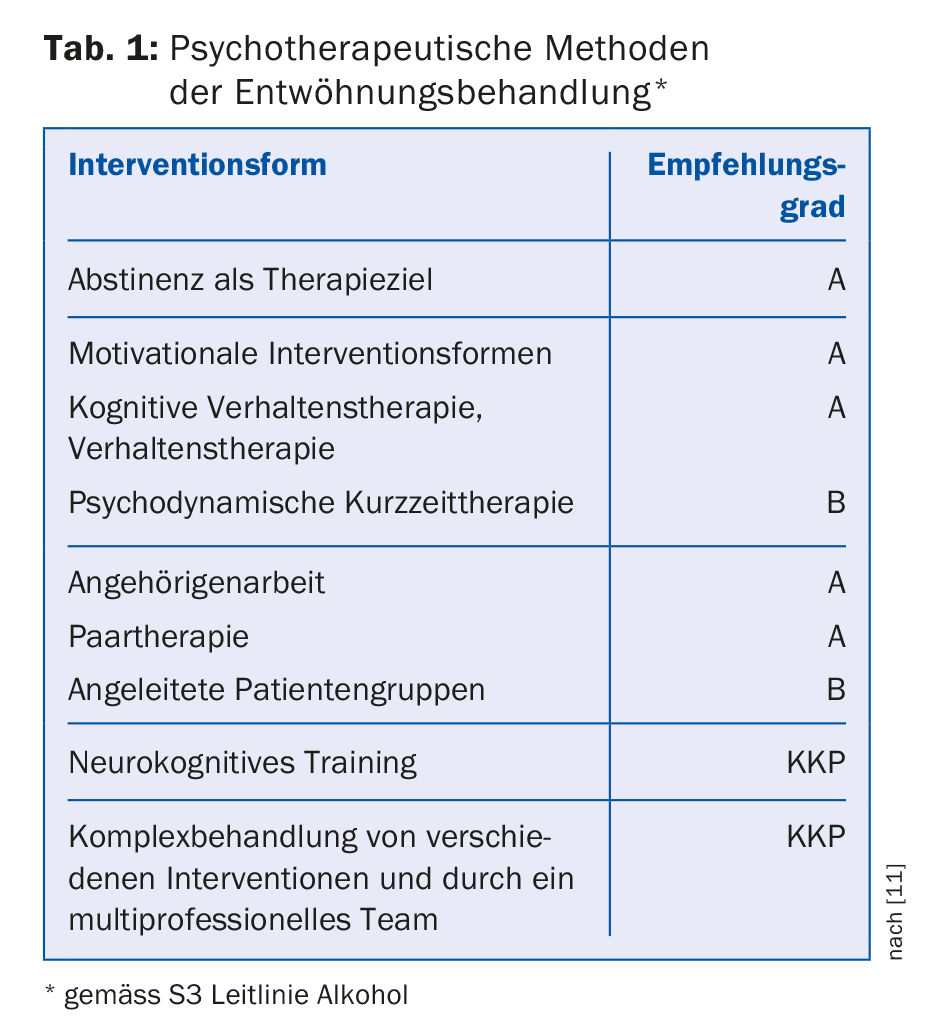

Addiction is more than substance use. It has a lot to do with situation, environment, group dynamics. The treatment is mainly about critical habits. To this end, it is important to establish an exchange on the topic with the patient (Tab. 1). Everyone compares themselves with heavy drinkers in their circle of acquaintances. This is where therapists need to get specific and personal, Ridinger recommends. “Let’s take a look at your liver, then.” Liver values can be very individual. Women are more likely than men to develop cirrhosis of the liver – but there are also genetic variants.

If there are no signaling toxic signs of excessive use and there are also no problems in the social sphere or at work, the reason for the conversation is not so obvious. Ridinger advises to then discuss ways to reduce alcohol consumption, “Can you imagine reducing however you can?” In such a conversation, controlled consumption gains a different perspective. It is not about should limits, may or may not, but about how the patient copes as a father, mother, as a human being, as an employee. Does consumption impair? Whenever alcohol is functionalized, it is a trap – statements are made like: “To become calmer” or: “To sleep better.” When alcohol is used to feel lighter, the patient has already created a dependence. This is often a first realization of addiction, namely that one’s internal state is dependent on a substance.

This perception often collides with the self-image of people as autonomous decision-makers. “After all, freedom begins with three options: If I always do the same thing, I am an automaton. Whenever I want to be relaxed and consume, I am an automaton. If I could do exactly two things, I have a dilemma. From three possibilities, freedom begins. Treatment is about increasing degrees of freedom and discussing possibilities.” Ridinger uses this equation to explain her approach to addressing this distorted self-image of addicts. Patients often have trouble shaping situations; they are stuck. Here, it may help to increase the degrees of freedom more slowly, at the speed of the particular patient. The patient chooses for himself.

As a therapist, Ridinger always asks if there was a problem with alcohol in the interim. If patients don’t respond or don’t want to talk about it, she leaves it at that. This is also a form of freedom. Insisting is useless. It’s important to ask questions to get into the conversation, he said. As a therapist, one should not judge. Moving means motivating, inquiring and changing within the scope of what is possible. Guilt blocks the process. Work must be done to help patients cope with their difficulties and setbacks.

Neurobiological mechanisms

Alcohol dependence is often secondary – as reward system activation. Primary alcohol dependence is rare. However, if the primary disorder is resolved, it does not mean that the alcohol dependence is resolved. Most disorders predate alcohol dependence. Statistically, this rarely develops before the age of 25.

However, there does not always have to be interference. With the activation of the reward system by alcohol, a good feeling is created, with which reward deficits are compensated, which also arise, for example, from high performance requirements or stress. To shed more light on lifestyle, it helps to find out how the patient “rewards” himself in everyday life with periods of rest, treats or other distractions. Reward procrastination is a mistake that can then lead to after-work beer. Among the many ways to activate the reward system, alcohol offers various advantages: It is effective, available, and not costly.

When alcohol creeps in as a solvent in such prolonged stressful situations, it becomes a habit. Even if at some point the insight to want to change something sets in, there is a neurobiological imbalance. Even if you increase degrees of freedom, the addiction, the habit effect remains. The brain looks for the easiest, familiar path. Habits are processed with the least amount of effort. Therefore, therapy must work together to establish new habits. When you establish new habits, they become easier. In this context, action determines thinking.

Medication

In primary care practice, when medications are used to support the patient’s efforts or when emergency intervention is required, there are two approaches. Alcohol mainly affects the messenger substances – the activating transmitter glutamate and the inhibiting transmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Alcohol activates neurotransmitters in the reward system, such as endorphins, serotonin, and especially dopamine. Medication can be used to reset dopamine release. When you take away alcohol, you have too much glutamate (restlessness, nausea, freezing) and too little GABAergic firing in the brain. Therefore, the GABAergic benzodiazepine is used.

In the long run, after all, you’re dealing with habits, so abstinence-induced dopamine deficiency leads to craving, the seizure-like craving. This is the most common reason for relapse. The reward system doesn’t have enough dopamine left. In the medium to long term, dopaminergic firing supports. The goal of medication is to find the right measure, since every patient reacts differently to treatment. Here, too, the focus is on the development of degrees of freedom.

The drug range is limited. Aversive treatment works very well for those patients who are optimistic. Disulfiram (Antabus®) [4,5] is a drug that prevents alcohol breakdown. This protects against consumption. It is poorly tolerated (flushing, tachycardia, vomiting) [6]. Disulfiram is slowly being withdrawn from the market because it is not catching on with patients.

Campral is a GABA analogue [7]; it has low bioavailability – you have to swallow at least six capsules – and causes digestive problems, so it has poor acceptability [8,9]. Naltrexone (Naltrexin®) has a dopaminergic (indirect GABAergic) effect via the opioid mechanism. In the case of naltrexone, alcohol shows a poorer effect because the drug competes with alcohol for binding sites [10]. Dizziness is an annoying side effect.

Nalmefene (Selincro®) is chemically similar to naltrexone as a partial agonist and antagonist in the opioid system. Treatment with nalmefene focuses on drinking reduction rather than abstinence maintenance. It is not comparable to other medications that rely on abstinence. The intake is recommended “as needed”. This is a modern therapeutic strategy that allows patients to decide for themselves, based on their experience, whether they need it. This triggers self-reflection, which is an important step in therapy. Studies by the manufacturer show that drinking quantities are reduced with it.

There is a limitatio for health insurance coverage: there must be chronic dependence with high dosages and the therapist must have known the patient for at least three weeks. Only then may the drug be used in combination with therapy. When additional addictions exist, the most severe withdrawal symptoms can result. This must be asked for by the therapist.

Source: SGAIM Fall Congress, September 14-15, 2017; presentation at SkillLab “Problematic Alcohol Use: What Moves the Patient?”

Literature:

- Addiction Monitoring Switzerland, Publications, www.suchtmonitoring.ch/de/page/9.html

- Global Drug Survey, www.globaldrugsurvey.com

- World Health Organization Europe, www.euro.who.int/de/health-topics/disease-prevention/alcohol-use/data-and-statistics/q-and-a-how-can-i-drink-alcohol-safely

- Ehrenreich H, Krampe H: Does disulfiram have a role in alcoholism treatment today? Not to forget about disulfiram’s psychological effects. Addiction 2004; 99 (1): 26-27.

- Laaksonen, et al: A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol & Alcoholism 2008; 43(1): 53-61. epub 2007.

- Bourdélat-Parks BN, et al: Effects of dopamine β-hydroxylase genotype and disulfiram inhibition on catecholamine homeostasis in mice. Psychopharmacology 2005; 183 (1): 72-80.

- Mann K, et al: Acamprosate: recent findings and future research directions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2008; 32 (7): 1105-1110.

- Anton R, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2006; 295. (17): 2003-2017.

- Mason BJ, et al: Effect of oral acamprosate on abstinence in patients with alcohol dependence in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: the role of patient motivation. Journal of psychiatric research 2006; 40 (5): 383-393.

- Graham R, et al: New pharmacotherapies for alcohol dependence. Medical journal of Australia 2002; 177 (2): 103-107.

- S S3 Guideline “Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Alcohol-Related Disorders” abridged version, AWMF Register No. 076-001 (as of Jan. 30, 2016) www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/076-001k_S3_Alkohol_2016-02_01.pdf

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(10): 41-44