Early death after childhood cancer diagnosis remains a challenge. Infants, ethnic minorities, and the socioeconomically worse off are at higher risk for early death. The reasons for this need to be further explored.

Until now, little is known about the characteristics of these children, and the exact reasons for their poor prognosis are insufficiently understood. In addition, the group is likely to be underrepresented in clinical trials. Early death after diagnosis (even before inclusion in a study) or such a critical health condition that participation seems impossible make them an elusive population. The previous state of knowledge comes from previous registry studies:

- An Italian study from 1967-1998 on deaths of children diagnosed with cancer only one month ago referred to risk factors such as age less than one year, disseminated disease at diagnosis, and certain types of cancer, e.g., acute myeloid leukemia (AML),non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, CNS and liver tumors [1].

- A second study from the well-known US SEER registry (1973-1995) found an increased risk in infants and similar associations with leukemia, CNS/liver tumors, and neuroblastoma, but at the same time no association with ethnicity [2].

- In addition, socioeconomic status is a key determinant of both diagnosis and outcome in childhood cancer, according to numerous other studies [3], although the specific association with early death has not been tested.

Which influencing factors decide on prognosis?

The study from the Journal of Clinical Oncology therefore sought to re-examine the extent to which cancer type, demographics, and economic conditions play a role in early death after cancer diagnosis. It also did so using the SEER registry, accumulating 36,337 cancer cases among people aged 0 to 19 years from 1992 to 2011. Early death was defined as death within one month of diagnosis. In addition, data were collected on the socioeconomic status of the patients’ respective administrative units (counties).

The results are similar to what is already known; overall, 1.5% of the total population, or 555 children, were affected by early death.

Children with AML had the highest risk of dying one month after diagnosis, as did those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in infancy, hepatoblastoma, and malignant brain tumors.

When various variables such as unemployment, poverty, education, and year of diagnosis were included in the analysis, age less than one year remained as a strong independent predictor, across all cancer types. For hematologic malignancies, it significantly increased the risk by a factor of 4.32, for CNS tumors by as much as a factor of 18.55, and for solid tumors by a factor of 5.34.

With regard to ethnicity, it could be observed that children of African American and Latino descent had a significantly higher risk of early death (risk increased by approximately 50-90% compared with white, non-Hispanic reference population, depending on cancer type). This result is difficult to explain because, after all, socioeconomic status was controlled for in the multivariable analysis. It remains to be seen whether (explosive) structural disadvantages caused by the health care system play a role here, or whether cultural and biological factors do.

Those who resided in a county with below-median median income also had a significantly higher risk (at least for hematologic malignancies)-by 51%.

Moreover, the number of deaths from hematological diseases in particular decreased significantly over the study period.

There is a need to catch up

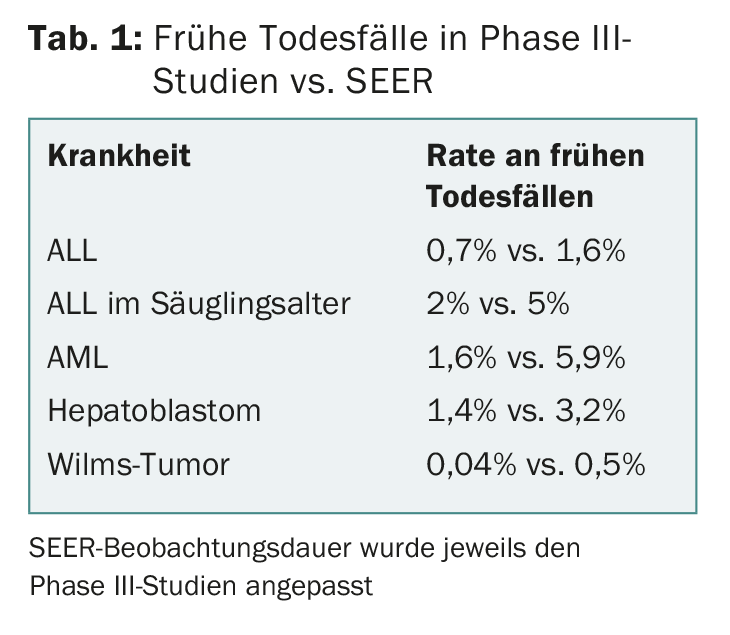

Important side note: Although early deaths decreased overall over the study period, the death rates collected were always significantly higher than could be expected based on clinical studies (tab. 1). This indicates that the study group is underrepresented in the current literature.

Furthermore, the difference suggests that many deaths in SEER were actually due to disease rather than treatment toxicity, as children were very likely to die before they could be enrolled in trials (which would explain the increased rates in SEER). This clearly distorts the results of clinical studies, i.e. a bias takes place, which is further reinforced by the lower chance of socioeconomically worse-off persons to participate in a study. In the future, therefore, the aim will be to identify and protect sick children at high risk of premature death at an early stage.

This task is anything but easy. Infants die significantly more often than older children, not least because they are not yet able to communicate feelings and pain linguistically, and thus pose challenges for medicine in the form of difficulties in interpretation as well as diagnosis.

Open questions remain

Green and colleagues’ analysis may help improve care for these high-risk patients, but it leaves the characterization of the cases open in one very crucial respect: the exact causes of death. Is it better infection control and supportive care for hematologic malignancies or modern therapies that have provided significant reductions in risk over time? Were the deaths mentioned consequences of acute life-threatening conditions or was progression of the disease itself responsible for the death? There is still a need for research.

The merit of the study therefore lies above all in the fact that this under-researched group of patients is thus coming increasingly into the focus of research.

Source: Green AL, et al: Death Within 1 Month of Diagnosis in Childhood Cancer: An Analysis of Risk Factors and Scope of the Problem. Journal of Clinical Oncology March 6, 2017. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.3249 [Epub ahead of Print].

Literature:

- Pastore G, et al: Early deaths from childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Registry of Piedmont, Italy, 1967-1998. Eur J Pediatr 2004; 163: 313-319.

- Hamre MR, et al: Early deaths in childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol 2000; 34: 343-347.

- Gupta S, et al: Low socioeconomic status is associated with worse survival in children with cancer: A systematic review. PLoS One 2014; 9: e89482.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(5): 3.