At this year’s Medidays in Zurich, various experts from the fields of psychotherapy and psychosomatics spoke about the potential of this form of therapy, for example in dealing with chronically ill patients or people who show psychosomatic symptoms due to traumatizing experiences of war or torture. The family doctor in particular, as the first point of contact for such conditions, should be well informed about the possibilities and limits of mental health treatment.

Although psychoeducation is anchored as a standard in guidelines, its application falls far short of recommendations, according to Prof. Michael Rufer, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital Zurich. “This form of treatment has great potential. The main goal of psychoeducation is not only to convey disease-related information or possible therapy strategies, but also to go beyond this first stage and teach people how to influence their own health. Among other things, active stress regulation and a functioning crisis management are aimed at.”

Good explanatory models of the course and symptomatology of a disease are crucial for success. They must be comprehensible and convincing and must not stigmatize the patient, but should rather leave room for individual content. Coping approaches can thus be specifically promoted. “For example, I recommend to primary care physicians what is called bibliotherapy: both the physician and the patient read a good self-help book and discuss the contents step by step,” Prof. Rufer explained.

Of course, psychoeducation, like all therapeutic approaches, also carries risks. In particular, the patient may feel overwhelmed or may find the knowledge of his or her disease psychologically stressful. Likewise, it is conceivable that by dealing with his problems as an expression of a disease, he may enter a passive state of acceptance. Therefore, it is even more important that psychoeducation is individualized and activating.

Dealing with war trauma

It is estimated that up to 150,000 people live in Switzerland who have been victims of torture or traumatizing war experiences. The wars in Bosnia and Kosovo in particular triggered waves of refugees between 1992 and 1999. Many of these people traumatized by war and torture do not appear as patients in the health care system. Even those with physical and psychological problems usually do not see themselves as victims of torture or war. Rather, they focus on psychosocial as well as socioeconomic difficulties related to residency, social isolation, uprooting, unemployment, or lack of economic prospects. Precisely because these individuals rarely consult a psychiatrist, the role of the treating primary care physician and his or her sensitivity to trauma becomes more relevant. Thomas Maier, MD, Chief Physician of the Cantonal Psychiatric Service in St. Gallen, therefore points out seven important principles for practice:

- In the case of certain countries of origin and biographies, think of the possibility of war and torture traumatization.

- Let them tell you, don’t interrogate them.

- Appreciate or value the life story. Do not relativize or trivialize, do not raise doubts. You have to try to understand that these people have experienced things that sound inconceivable to you.

- Take symptoms seriously and clarify them precisely. If necessary, also arrange for additional examinations, but do not lapse into heroic actionism. Don’t look for the quick, total solution to the problem.

- Work out a suitable explanatory model together with the patient. Usually the “body memory” model is well understood (body can remember pain even if the head has forgotten it). Avoid terms with the word part “psycho” at all costs, as such have very negative connotations in many Balkan countries.

- Offer relationship, reliance and authenticity.

- In addition to trauma, take into account real current life situation (migration problems).

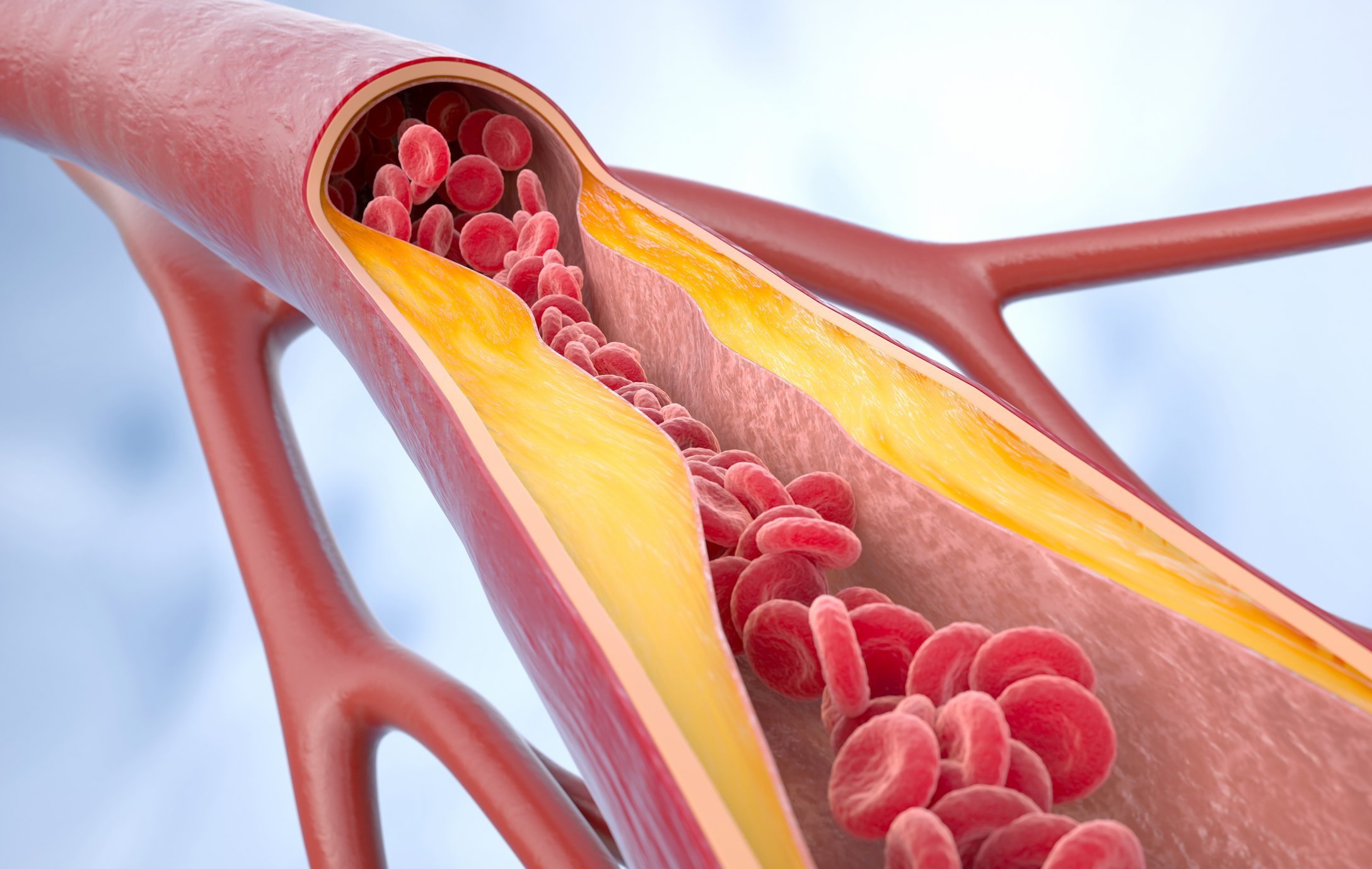

How to deal with chronic diseases?

The last speaker was Prof. Dr. med. Silke Bachmann, Medical Director of Clienia Littenheld AG, who addressed the question of what issues and burdens chronically physically ill patients have to deal with. First of all, of course, there is the fact that the disease is largely irreversible or even progressive. How does the patient deal with it? How does he cope with the constant dependence on medical specialists? In any case, with a chronic disease, physical integrity suffers and personal performance decreases. Furthermore, the unpredictability of the course of the disease and the repeated spatial separation from relatives (hospitalization) means a great burden. Concerns about the private and professional future are added.

“Here, the physician must specifically inquire about the subjective experience and evaluation of the illness and promote or increase self-competence. Hopelessness and shame in particular, but also not wanting to admit it, should be addressed directly. The goal is to draw attention to individual resources, e.g., using the questions: When have you ever succeeded in changing something? How did you do it? Who helped you to do it? What did you need to do it? Who and what can help you today?” says Prof. Bachmann. Continuous medical support enables appreciation of what has been achieved, which in turn is important for motivation.

Possible interventions are, in addition to education, supportive conversation, self-help groups, couple/family discussions, relaxation procedures, social services, rehabilitation, crisis intervention with or without psychotropic drugs, psychotherapy or, if necessary, end-of-life care.

Source: “Psychiatry – Psychosomatics”, Seminar at Medidays, September 2-6, 2013, Zurich.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8(9): 46-47