On January 24, the Swiss Derma Day took place in Lucerne for the second time. The University Clinics of Dermatology Basel and Inselspital Bern, in collaboration with the clinics of Aarau, Bellinzona, Lucerne and the Triemlispital Zurich, have again invited to this training event. The comprehensive program included an update on contact dermatitis and an overview of the management of hyperhidrosis.

Dr. med. Kathrin Scherer, Basel, presented news on contact dermatitis. “Allergic contact dermatitis is a common medical problem, with 15% of the population sensitized to a standard-range allergen,” she explained. However, due to newly emerging substances, the exposure is constantly changing. Therefore, the Information Network of Dermatological Clinics (IVDK) based in Göttingen constantly monitors and evaluates the situation. The approximately 50 hospitals participating in the IVDK also include four from Switzerland. An update of the collected data is published every two years [1].

Nickel, fragrances and preservatives

In 2010, 12,574 patients underwent epicutaneous testing in the dermatology departments participating in the IVDK [1]. The most common contact allergen is still nickel. “In general, however, the sensitization rate for metals is declining, especially when viewed over the long term,” Dr. Scherer added. “Nonetheless, the nickel sensitization rate among women aged 18 to 30 years remains around 20%.” Sensitization rates to cobalt and chromium are also on the decline.

This is due in particular to the fact that the use of these substances has been more closely regulated in recent years, according to Dr. Scherer. For example, the use of low-chromate cement has led to a decrease in new sensitizations to chromate among bricklayers.

Fragrances are the second most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis after metals. “Again, sensitization rates have decreased significantly over the past 13 to 14 years. This is mainly due to a reduction in the concentrations of oakmoss absolue and isoeugenol in cosmetics and personal care products,” she said. In the last three years, however, there has also been a slight increase in new sensitizations here. “This is likely explained by a relative increase in allergic reactions to the other fragrances included in each mix.”

The third major group among the leading allergens are preservatives. Sensitization rates to MCI/MI (methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone) show a marked increase after a prolonged constant phase. Since 2005, MI has also been used alone, without MCI, as a preservative. “The maximum amount permitted for MI is limited to 100 ppm in cosmetics. However, no limit exists for industrial use, e.g. in wall paints,” the expert explained. A study of painters found that MI and epoxy resin were the two most common allergens [2]. In other studies, study participants already reacted to MI concentrations between 5 and 50 ppm in e.g. rinse-off products and wet hygiene wipes [3, 4]. Furthermore, Dr. Scherer pointed out the importance of the preservative IPBC (iodopropynyl butylcarbamate). “IPBC is the second most common allergen in the preservative group. Metal- and wood-processing occupational groups are particularly affected here.” This substance has also been present in cosmetics and hygiene wipes for a few years. “IPBC is not a particularly strong allergen, but it penetrates very well because it is a small, lipophilic molecule. So it’s a substance we should expect to see in the future,” she concluded.

When sweating becomes a problem

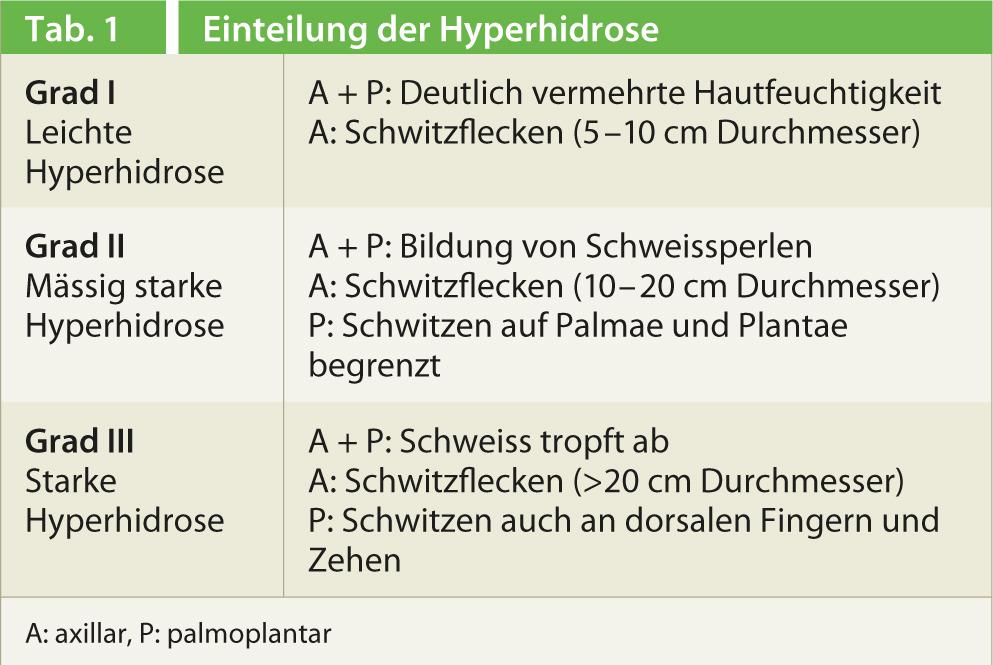

Sweating is a physiological, vital process that protects the organism from overheating. In hyperhidrosis, there is an excess of sweating beyond the requirements of thermoregulation. “Hyperhidrosis is not at all rare in this context,” explained Markus Streit, MD, Aarau, at the beginning of his presentation. Work from the USA found a prevalence of 2.9% [5]. “Men and women are equally affected. However, mainly young people, i.e. children, teenagers and young adults suffer from it.” The AWMF S1 guidelines classify hyperhidrosis clinically according to severity(Tab. 1) [6]. Hyperhidrosis is very debilitating. For example, studies have shown that quality of life is more impaired by hyperhidrosis than by vitiligo, severe acne, or psoriasis, for example [7].

Etiologically, a distinction is made between primary (idiopathic) and secondary hyperhidrosis [6]. “Primary hyperhidrosis has a typical focal symmetric pattern,” Dr. Streit said. The predilection sites are armpits, palms, soles and forehead. “Hyperhidrosis typically begins during puberty, sometimes as early as childhood or in adolescents.” It is a resting sweat that is not effort- or heat-dependent. “Unlike secondary hyperhidrosis, primary hyperhidrosis does not involve night sweats,” the speaker added. Secondary hyperhidrosis is caused, for example, by an underlying disease such as hyperthyroidism or diabetes mellitus. However, secondary hyperhidrosis can also occur during menopause or with the use of certain medications (parasympathomimetics, glucocorticoids, antibiotics, antidepressants, etc.). “But, of course, you have to think about conditions in which the basal metabolic rate of the body is elevated, such as tumors or infections,” Dr. Streit emphasized.

According to the AWMF guidelines, routine laboratory and imaging tests are not indicated for the diagnosis of primary hyperhidrosis in the absence of clear evidence of secondary hyperhidrosis [6]. The iodine strength test according to Minor can be used to color-code the actively secreting area, e.g. in the axilla. However, the test does not allow quantitative statements to be made.

Therapy of primary hyperhidrosis

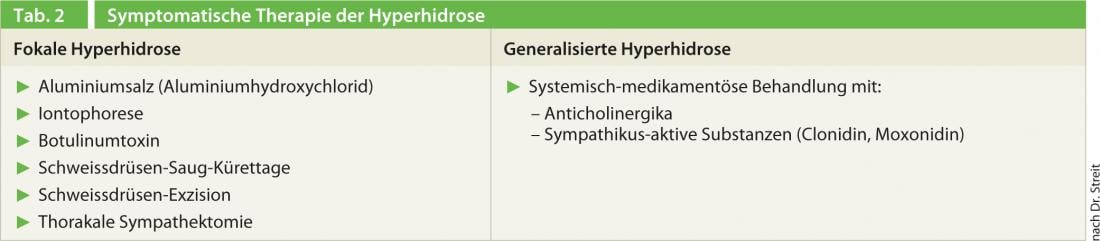

Treatment of primary hyperhidrosis is symptomatic. “An important prerequisite for therapy is recognizing the sweating pattern, i.e., whether it is focal or generalized sweating,” the speaker explained. “For generalized hyperhidrosis, medications are used; for focal hyperhidrosis, we stick to local measures”(Table 2). Intracutaneous injection of botulinum toxin A into hyperhidrosis areas is among the most effective methods for reducing excessive sweating [6]. Botulinum toxin A reversibly blocks the autonomic cholinergic postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers. Acetylcholine is no longer released and the eccrine sweat gland is thus chemically denervated. However, the effect wears off after about six months as new nerve endings sprout into the area. “Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis, but it is covered by insurance companies only if supplemental insurance is available,” Dr. Streit indicated.

In the axilla, sweat glands can also be surgically excised or removed by suction curettage. Dr. Streit studied the effect of suction curettage himself in 27 patients. “I was able to determine that a good effect could be achieved in the short term, but not in the long term.” That’s why he rarely uses this technique anymore. During thoracic sympathectomy, the borderline ganglia supplying the sweat glands are either completely severed, coagulated, or clamped with a metal clip. “The rate of surgical complications is low, but compensatory hyperhidrosis occurs in virtually 100% of cases and is also relevant in about 50% of cases,” Dr. Streit made clear. Hornberg et al. have proposed a graded treatment plan for focal hyperhidrosis depending on its location (axillary, palmar/plantar, or forehead/head) [9]. Anticholinergics such as atropine sulfate inhibit the action of acetylcholine by blocking the receptor. “The problem with anticholinergics is that they also affect other glands, such as salivary and lacrimal glands. This leads to side effects such as a dry mouth or visual disturbances. In my experience, about 50% of patients do not tolerate anticholinergic treatment and do not show any effect. You have to test this out on an individual basis.” Sympathetic-active substances such as clonidine or moxonidine are usually better tolerated than anticholinergics. Dr. Streit summarized, “So we can attack many places to influence excessive sweating. The most important prerequisite for therapy here is to identify the sweating pattern in each patient.”

Source: 2nd Swiss Derma Day, Lucerne, January 24, 2013

Literature:

- Geier J, et al: Der Hautarzt 2011; 62: 751-756.

- Mose AP, et al: Contact Dermatitis 2012; 67: 293-297.

- Lundov MD, et al: Contact Dermatitis 2011; 64: 330-336.

- Lundov MD, et al: Br J Dermatol 2011; 165: 1178-1182.

- Strutton DR, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 51: 241-248.

- AWMF S1 guideline: Definition and therapy of primary hyperhidrosis. Available at www.awmf.org/leitlinien.html

- Swartling C, et al: Eur J Neurol 2001; 8: 247-252.

- Streker M, et al: Dermatologist 2010; 61: 139-144.

- Hornberger J, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 51: 274-286.