As a meeting place of people from diverse habitats and -absections, the physician’s office represents a potential hotspot for infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The importance of good prevention is correspondingly high. This is important not only to protect vulnerable individuals, but also to be able to maintain health care services.

Medical practices closed for quarantine reasons and infections of staff and patients must be avoided. Thus, medical practices are also officially required to comply with hygiene and distance rules [1]. But what is the best way to implement this commitment?

Know transmission paths

In order to optimally counter the risk of infection, it is important to know the transmission routes of the virus and thus to be able to identify critical situations and processes. In principle, the virus is most often transmitted during close and prolonged contact. And the longer and closer this contact is, the more likely infection is. Although we would like to take our time with our patients, a focused, structured and well-prepared consultation makes sense in the current situation to minimize contact time.

Droplets, aerosols, surfaces, and hands are the main routes of transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. When breathing, speaking, sneezing or coughing, droplets containing viruses can get directly onto the mucous membranes of other people in the immediate vicinity. This is also where the famous 1.5 meter rule comes from. Likewise, transmission by aerosols – i.e. very fine droplets – over greater distances is possible, but occurs much less frequently. It plays a role mainly in activities with increased breathing and in poorly ventilated rooms, especially small ones. Infectious droplets on hands and surfaces provide an additional source of infection.

It is often the air

With air dryness, longer stays indoors and less motivation to ventilate, the cold season exacerbates the risk of infection via aerosols. Mouth-to-nose protection with a surgical mask can significantly reduce the expulsion of viruses, but not stop it completely. The combination of different measures promises the most success in maintaining air quality [2]. These include, for example, regular ventilation, the use of a humidifier and the targeted use ofCO2 monitors. If ventilation is not sufficient, it is recommended to purchase an air purifier.

At relative humidity around 50%, human mucous membranes are most resistant to infection and viruses survive in aerosol particles for less time than in drier or more humid air [2]. Reason enough, therefore, to keep the humidity at 40 to 60% with the help of a humidifier – especially in the doctor’s office.

The fresh air supply can be controlled by usingCO2 measuring devices. When the carbon dioxide concentration reaches a value of 1000 ppm, it is high time to open the window. Because this indicates that there is a lot of exhaled air – and therefore potentially a lot of virus – in the room. In a recent paper published by the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) in collaboration with researchers from New Delhi, Rome, and Colorado, a minimum efficiency of MERV-13 (Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value; US standard) is recommended for the ventilation and air conditioning system [2]. This ensures that even small particles are filtered out of the air.

In cases where adequate ventilation is not possible, air purifiers can be used to reduce the concentration of virus in the air. However, these cannot replace the supply of oxygen and fresh air. It is important that they have a so-called HEPA (High Efficiency Particle Absorbing) filter.

In addition to the use of air hygiene aids and consistent ventilation, aerosol-generating processes should be avoided if possible in the current situation. This includes, for example, the use of medications administered via a nebulizer. A metered dose inhaler is a less dangerous alternative. The entire overview of potentially aerosol-forming activities is accessible on the Swissnoso website. To estimate and illustrate the transmission risk from aerosols, the Max Planck Institute has developed the “COVID 19 Aerosol Transmission Risk Calculator”. an easy-to-use online tool for risk calculation [6].

The choice of the right protective material

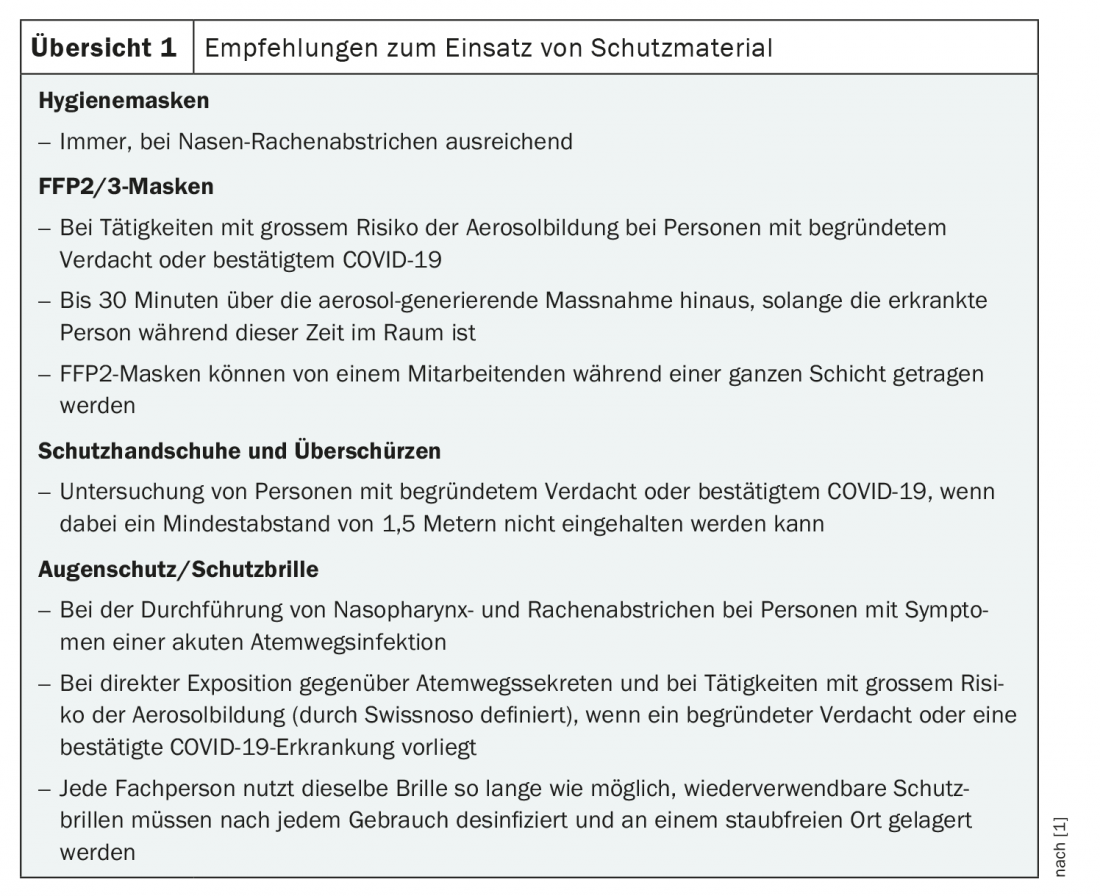

In addition to sufficient distance, regular disinfection of materials and surfaces, clean air and good hand hygiene, protective material can also contribute significantly to safety in the medical practice (overview 1) . In principle, clothing should be changed daily and worn exclusively in the practice. Tying back long hair prevents unnecessary grabs to the face [3].

In doctor’s offices there is a general obligation to wear masks for staff, patients and accompanying persons. If no strong aerosol formation is to be expected, the wearing of hygiene masks is sufficient here. This also applies to the performance of smears. However, if the risk of aerosol formation is high and COVID-19 is suspected or even confirmed, the FOPH recommends that healthcare workers wear an FFP2/3 mask [1].

And what about protective gloves, aprons and goggles? Their use is extremely useful depending on the situation (overview 1) . If the distance of 1.5 meters from suspected patients or those with a confirmed COVID-19 infection cannot be maintained, additional protection by means of an overapron and protective gloves is indicated. Safety glasses are recommended in those situations where the risk of aerosol formation is high or direct exposure to respiratory secretions may occur. Eye protection should also be worn when performing nasopharyngeal swabs on individuals with symptoms of acute respiratory infection [1].

Not only must the presence of these protective materials be ensured, but also their correct handling. Here, well-rehearsed processes in the team are certainly an advantage and appropriate coaching is time well spent. Materials that are readily available at any time – especially masks and disinfectants – make it easier not only for patients to implement protective and hygiene measures, but also for practice staff.

Actively manage patient pathways

The best prevention of infection is and remains to avoid personal contact as much as possible. This is where telemedicine comes into play, on the one hand, and actively managing patient pathways in the practice, on the other. Where possible, telephone consultations can be used, for example. While this is a fine line in terms of quality of care, it can work well on a selective basis. The presence of accompanying persons should be kept to a minimum.

To avoid accumulations of patients, there are no limits to creativity. For example, in addition to thinning out the seating in the waiting area, floor markings, barriers, time and/or space separated COVID-19 consultations, or appointment slots may be introduced. Depending on the premises, the separation of patient pathways may look different. Recommendations that apply to all practices include removing magazines and other materials that potentially pass through multiple hands and keeping doors open. In this way, infections via the door handle can be prevented. If this is not possible – for example, for reasons of privacy – door handles as well as other surfaces must be disinfected regularly.

Not only can active management of patient pathways contribute to safety in the practice, but so can deliberate planning of staff assignments. For example, if work is always done in the same teams, contacts with each other can be reduced. There is a high risk of infection, especially during breaks. Here it is important to observe the rules of hygiene, even when eating and chatting. This aspect is often overlooked in the hectic daily routine of the practice and must not be neglected when planning measures. Where possible, home office may also be an option in medicine. The high documentation requirements of our time also have their advantages in this respect.

Hopefully, the application of these measures will keep as many practices open as possible and provide care during this challenging time. Also from non-Corona patients.

Information sources

Further information can be found on the websites of the FMH, Swissnoso and the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), among others [1,3,4]. The German guideline “Pandemic Planning in the Medical Practice” [5] is also helpful. This contains checklists and sample templates, some of which are also suitable for use in Switzerland or can be easily adapted for this purpose.

Literature:

- FOPH: Coronavirus: protective concepts and measures. www.admin.ch/bag/ (last accessed on 15.01.2021)

- Ahlawat A, et al: Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Hospitals and Nursing Homes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(22).

- FMH: COVID-19: FMH protection concept for the operation of medical practices. 29.12.2020. www.fmh.ch (last accessed on 15.01.2021)

- www.swissnoso.ch (last accessed on 15.01.2021)

- Dorbath M, Lupo C: Pandemic planning in the physician’s office – A guide to dealing with Corona. Competence Center (CoC) Hygiene and Medical Devices of the Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the Federal Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians; 2020. www.kbv.de/html/1150_48655.php (last accessed on 15.01.2021)

- Max Planck Institute: COVID 19 Aerosol Transmission Risk Calculator. https://www.mpic.de/4747361/risk-calculator (last accessed on 17.01.2021)

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(1): 39-40 (published 2/24/21, ahead of print).

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(1): 34-35.

CARDIOVASC 2021; 20(2): 35