As a symptom of many dermatologic but also internal diseases, chronic pruritus poses a challenge to dermatologists and primary care providers alike. About diagnosis and therapy of this common disease.

Chronic pruritus is defined as itching that persists for more than six weeks. Approximately 14-17% of the population is affected by chronic pruritus, which is ranked among the 50 most significant diseases worldwide. For the affected patients, it represents a great burden with a severe restriction of the quality of life, and for the treating physician it is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge [1].

The neurophysiological processes involved in chronic pruritus are not fully understood. In most cases, no single and clearly definable trigger exists. Rather, chronic pruritus arises from a complex interaction between keratinocytes, immune cells in the skin, and the peripheral and central nervous systems. This interaction is mediated by a variety of mediators such as substance P and the interleukins (IL) IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, which act on receptors of the corresponding target cells [2]. The immune cells of the skin involved, which play a role especially in itching in chronic inflammatory skin diseases, include mast cells and eosinophilic granulocytes. These cells appear to accumulate in particular topographic proximity to peripheral nerve fibers in the skin in atopic dermatitis. In addition to the well-known histamine, mast cells secrete other mediators that can lead to activation and even hyperplasia of peripheral nerve fibers and thus trigger itching. Eosinophilic granulocytes release mediators similar to those released by mast cells and thus may also contribute to itching in chronic inflammatory skin diseases. Recently, it was shown that eosinophilic granulocytes release IL-31, which increases peripheral nerve fiber growth, possibly promoting itch [3].

Chronic pruritus is a frequent symptom of numerous dermatological and internal diseases. Since this article is aimed at a wide range of specialists from primary care physicians to dermatologists, pruritus in common internal or systemic diseases as well as exemplified by a common chronic skin disease, namely atopic dermatitis, will be discussed below.

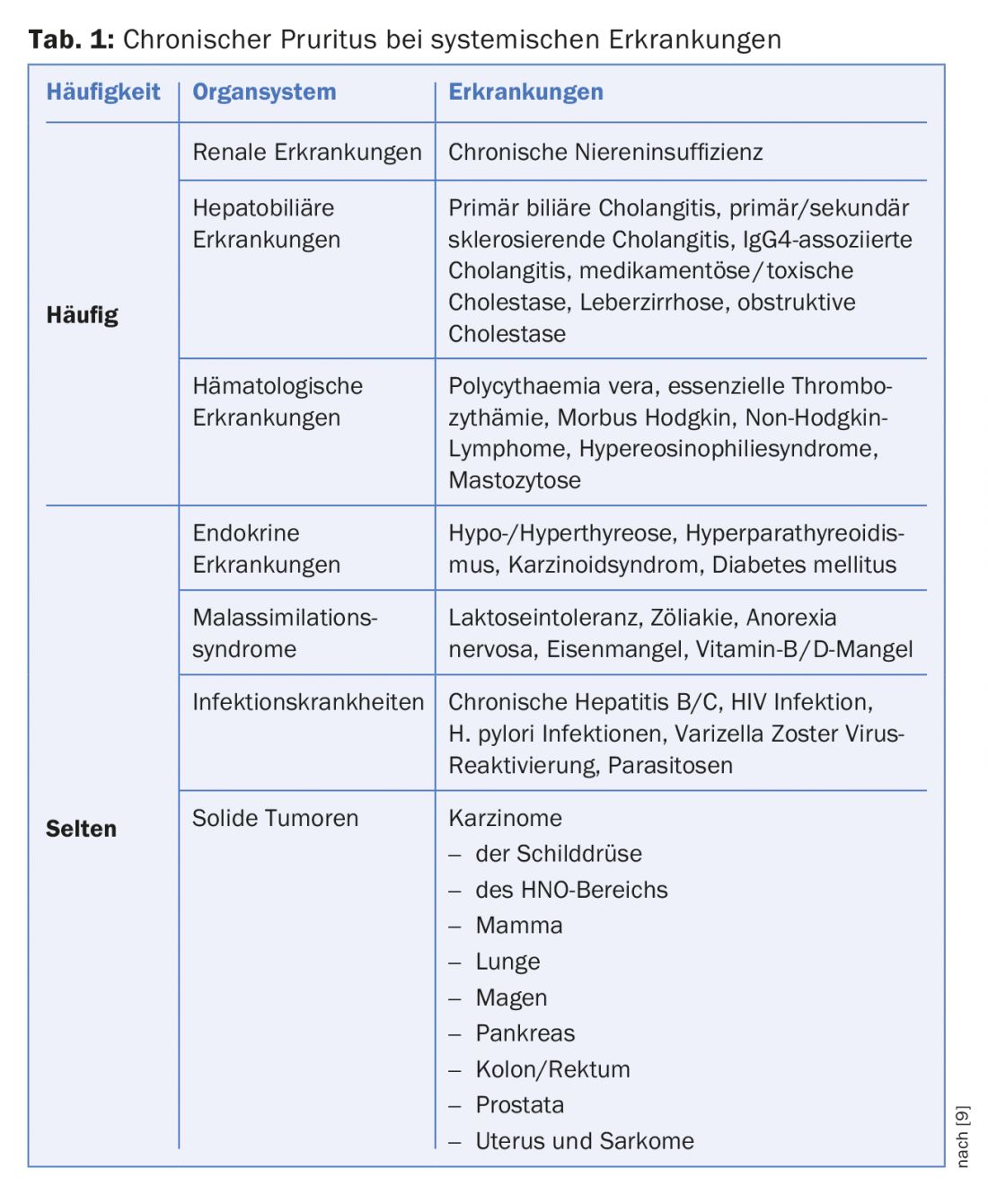

Chronic itching in internal diseases

As shown in Table 1, renal, hepatobiliary, and hemato-oncologic diseases are the most common systemic diseases that may be associated with chronic pruritus. Initially, patients usually suffer from pruritus without skin lesions, so this form is typically referred to as “pruritus on noninflammatory skin” (formerly called “pruritus sine materia,” although this term should no longer be used). In the course of the disease, the constant scratching causes the secondary florescences typical of pruritus, such as excoriations, sometimes with crusting, pigmentary shifts, scars and often also prurigo nodules.

Pruritus in renal diseases

Nephrogenic pruritus typically occurs in patients with chronic renal failure, whereas patients with acute renal failure or renal disease without decreased renal function usually do not have pruritus. Up to 50% of all patients requiring dialysis complain of pruritus. Half of the patients report pruritus over the whole body, while the remaining patients are mostly affected on the head or back [4]. The exact mechanism leading to pruritus in chronic renal failure remains unclear. Very different factors seem to play a role, such as the skin dryness and damage to nerve fibers caused by renal insufficiency, as well as the increased release of known itch mediators such as substance P.

No therapy generally recognized as effective exists for nephrogenic pruritus. The basis of any antipruritic therapy must be consistent refatting of the skin. In addition, corticosteroids, the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus, or capsaicin (an extract of chili pepper) are often applied topically. This often leads to success in mildly to moderately affected patients and regular use. Commonly used systemic therapeutics include the calcium channel blockers gabapentin and pregabalin [4]. A recent review reaffirms the good therapeutic outcome of phototherapy and photochemotherapy for chronic pruritus in internal and inflammatory skin diseases [5]. Finally, nephrogenic pruritus usually improves when chronic renal failure itself is successfully treated, for example, by renal transplantation.

Pruritus in hepatobiliary diseases

A variety of diseases of the liver and biliary tract system may be associated with chronic pruritus (Table 1) . The frequency of affected patients with pruritus varies greatly depending on the disease and ranges from 15% of patients with chronic hepatitis C to 100% of all patients with pregnancy cholestasis. Pruritus can often be generalized, but usually affects the extremities and the palms and soles of the feet. The pathogenetic mechanisms leading to pruritus, as in nephrogenic pruritus, are not conclusively understood.

The basis of therapy is the treatment of the underlying disease, which, if possible, can lead to an improvement of the itching very quickly. If this is not possible or difficult, such as in intrahepatic cholestasis, ursodeoxycholic acid is very commonly used. This is well effective in gestational cholestasis, but often inadequate in other forms of cholestasis such as primary biliary cholestasis or primary sclerosing cholestasis. Many reviews recommend the use of cholestyramine, rifampicin, naltrexone, or sertraline [6].

Pruritus in oncological diseases

About 5-7% of all patients with chronic pruritus suffer from an oncological disease. Hematooncological diseases are particularly noteworthy. A typical example is polycythemia vera, a myeloproliferative disease in which there is an increase in all three blood cell series, especially erythrocytes. Thus, up to two thirds of all patients with polycythemia vera suffer from chronic pruritus, especially after contact with water (aquagenic pruritus). In another hematooncologic disease, Hodgkin’s disease, a B-cell lymphoma, up to half of patients develop pruritus, some of which is excruciating. In most cases, the skin of affected patients is clinically completely inconspicuous. The onset of pruritus may precede the actual manifestation of a new Hodgkin’s disease by years, but it may also herald a recurrence of a known Hodgkin’s disease. Therefore, patients with causally unexplained chronic pruritus should undergo regular hemato-oncologic screening. For the treatment of chronic pruritus in hemato-oncological diseases, the underlying disease should be treated on the one hand, and gabapentin and pregabalin, as well as acetylsalicylic acid or mirtazapine are also recommended.

In addition to hemato-oncologic diseases, solid tumors of any origin may rarely be the cause of chronic pruritus. The pathophysiologic relationships are not clear, but treatment of the underlying malignancy is the therapy of choice.

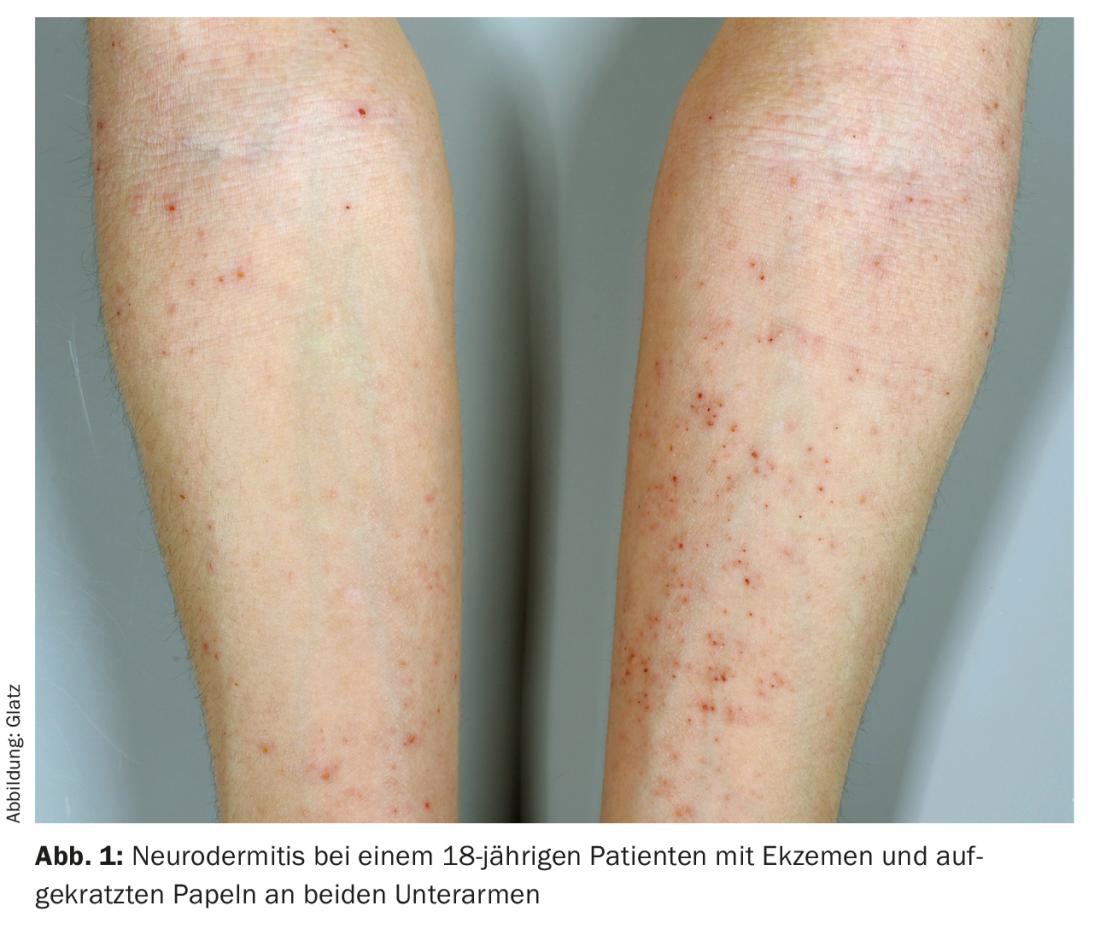

Chronic pruritus in inflammatory skin diseases. Example: Neurodermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic disease characterized by itchy skin eczema [7]. Atopic dermatitis is a very common skin condition, affecting 15-30% of children and up to 10% of adults. The relapsing course of neurodermatitis is typical, with phases of eczema and itching alternating with periods of often complete freedom from symptoms. Triggers for disease flare-ups vary from patient to patient, but often include mechanical irritation such as friction from clothing, sweating and, of course, neglect of therapy. Even more than the recurring eczema, the often massive itching has a negative impact on the quality of life of neurodermatitis patients. The pruritus is usually worst at night and thus leads to sleep disturbances with concentration problems and reduced performance during the day up to psychological stress states.

The most important therapy for atopic dermatitis and the pruritus that accompanies it is consistent, daily, and usually lifelong rehydration of the entire skin [8]. Every neurodermatitis patient must be instructed in the correct use of this basic therapy by his treating physician. The cream should be applied twice a day in the morning and evening. Creaming is done from the head, from the top down, to the feet. Every part of the body must be creamed, even the eczema-free and non-itchy skin. Skin areas with visible eczema and/or existing itching must be creamed with an anti-inflammatory cream or ointment 15-30 minutes after the refatting therapy. Steroid preparations or steroid-free topical calcineurin inhibitors are available for this purpose. Steroids are used once a day. Modern, double-esterified steroids should be used. Topical calcineurin inhibitors must be applied twice daily but are weaker in their effect than most steroids [8]. Additionally, UV therapy is a very effective treatment option for both eczema and pruritus.

New therapies for chronic pruritus

Recently, the first effective biologic available for the treatment of atopic dermatitis is the IL-4/IL-13 receptor antagonist dupilumab. Many patients report a marked improvement in pruritus even before improvement in eczema. Other antibodies that have shown efficacy against pruritus in inflammatory skin diseases in clinical trials are directed against IL-31 and IL-17. Therapeutics with promising potential are the “small molecules” crisaborole and tofaticinib, of which crisaborole has recently been approved for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis in the USA. Another therapeutic option of the future may be neurokinin receptor antagonists, which prevent the release of substance P, and also seem to be effective in pruritus caused by systemic diseases. In any case, further innovative therapies will be tested in the coming years, at least in clinical trials.

Literature:

- Steinke S, et al: Humanistic burden of chronic pruritus in patients with inflammatory dermatoses: results of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Network on Assessment of Severity and Burden of Pruritus (PruNet) cross-sectional trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79(3): 457-463.e5. Epub 2018/08/19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.044.

- Mollanazar NK, Smith PK, Yosipovitch G: Mediators of Chronic Pruritus in Atopic Dermatitis: Getting the Itch Out? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016; 51(3): 263-292. Epub 2015/05/02. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8488-5.

- Feld M, et al: The pruritus- and TH2-associated cytokine IL-31 promotes growth of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138(2): 500-508.e24. Epub 2016/05/24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.020.

- Malekmakan L, et al: Treatments of uremic pruritus: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther 2018:e12683. Epub 2018/08/25. doi: 10.1111/dth.12683.

- Legat FJ: Importance of phototherapy in the treatment of chronic pruritus. Dermatologist 2018. Epub 2018/07/15. doi: 10.1007/s00105-018-4229-z.

- Mittal A: Cholestatic Itch Management. Curr Probl Dermatol 2016; 50: 142-148. Epub 2016/09/01. doi: 10.1159/000446057.

- Bieber T: Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(14): 1483-1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081.

- Ring J, et al: Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26(8): 1045-1060. Epub 2012/07/19. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04635.x.

- Kremer AE, Mettang T (2016). Pruritus in systemic diseases. Common and Rare. Der Hautarzt 2016; 67(8): 606-614.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(5): 10-13