The clinic of degenerative changes is difficult to distinguish from that of peripheral arterial disease (PAVD), and measurement of ABI is indicative.

Exertional leg pain (intermittent claudication) is a common reason for medical consultation. Particularly in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, intermittent claudication is due to peripheral arterial disease (PAVD), also known as “window shopper’s disease.” The cause of PAVK is with more than 90% arteriosclerosis with the known main risk factors age, cigarette smoking, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus as well as genetic predisposition. In addition to the chronic form, acute ischemia of the extremities may occur less frequently. Causes of acute ischemic events are embolic or locally thrombotic arterial occlusions. In both cases, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) values are pathological (Table 1). In intermittent claudication, a vascular cause with a pathological ABI value is distinguished from a non-vascular cause with a normal ABI value (Table 2).

Rare vascular causes with pathologic ABI.

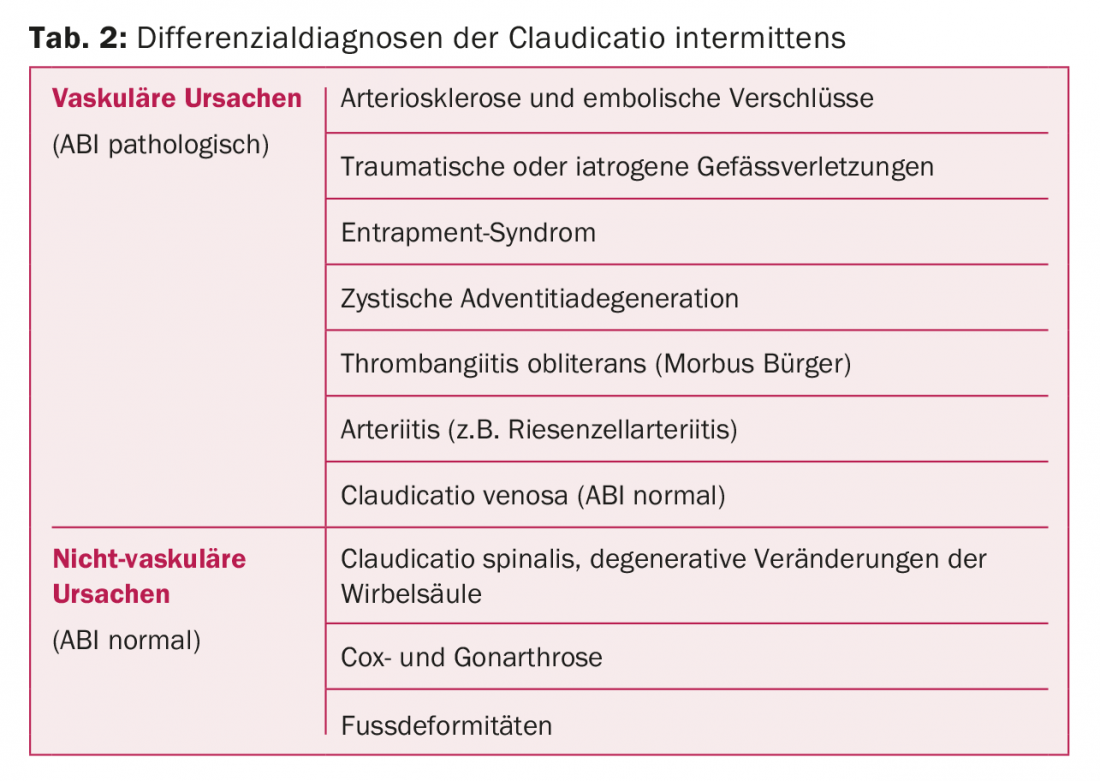

Traumatic or iatrogenic causes: A major symptom of traumatic or iatrogenic causes of vascular injury is acute onset of symptoms in temporal proximity to trauma or intervention (PTCA or PTA). The cause of arterial dissection by trauma is often distortion with shear forces acting on the vessels. Arterial dissection is usually an emergency situation because – in contrast to arteriosclerotic acute-on-chronic occlusion of the artery – the collateral circulation formed by chronic ischemia is absent (Fig. 1) . Traumatic arterial dissections should be remembered especially after whiplash (carotid or vertebral artery) or after a

Distortion of the extremities to think about. Iatrogenic vascular injury becomes symptomatic immediately after surgery or catheter-based interventions such as PTCA or PTA and affects the extremity perfused by the affected artery.

Popliteal entrapment: This is a rare cause of intermittent claudication, mainly in the younger male patient. Due to an altered position of the popliteal artery caused by embryonic development or altered insertion sites of the medial gastrocnemius muscle, the popliteal artery is mechanically compressed. Less commonly, the soleus or popliteus muscle in the popliteal fossa causes constriction. Functional entrapment syndrome is possible due to muscle hypertrophy in (strength) athletes. Clinically, the symptoms are highly variable and often not typical of an incipient circulatory disorder. In some cases, claudication can occur after only a few meters. Critical ischemia may present with symptoms such as rest pain or skin defects. Diagnostically, pulse status or duplex sonography at rest and under provocation (plantar flexion with the knee extended) provide evidence of entrapment syndrome. Imaging is performed with MR angiography or angiography in the provocation position.

The therapy of choice is surgical pressure relief. If the arterial wall is not yet damaged by the constant compression, the compressing structures alone can be cut. If damage is already present, PTA, surgical vascular reconstruction, or even femoropopliteal or femoral arthroplasty must be performed. crural bypass will be discussed.

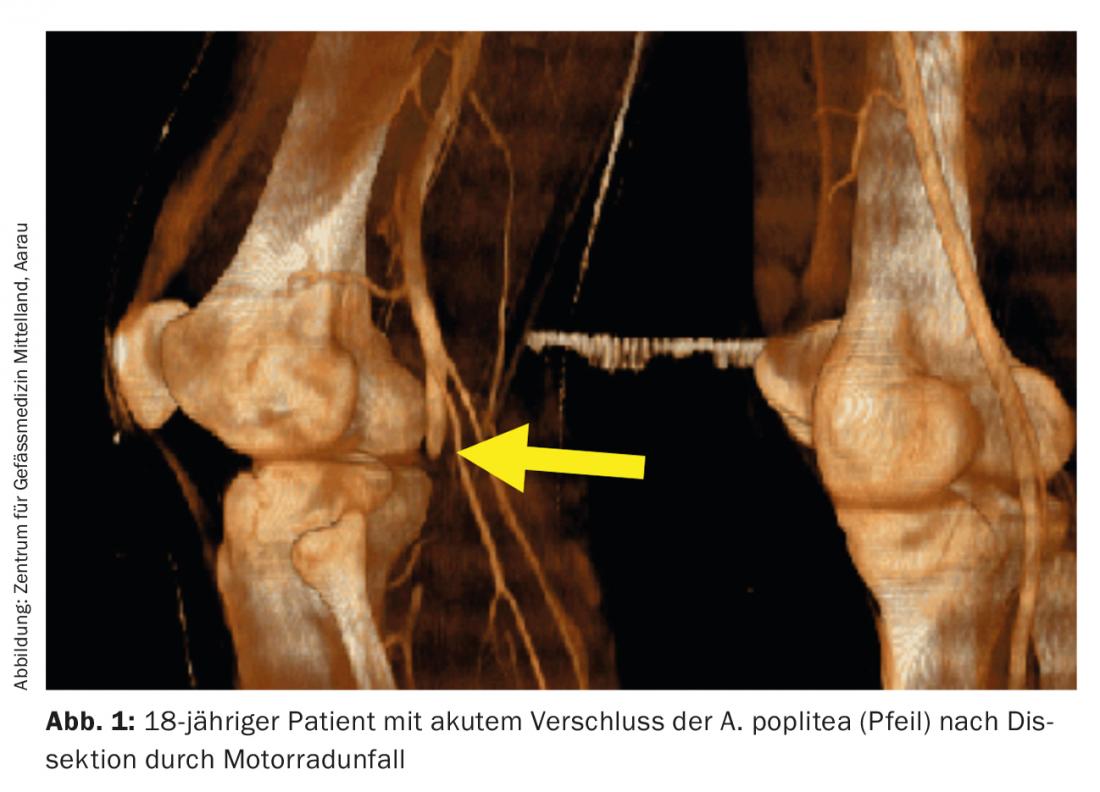

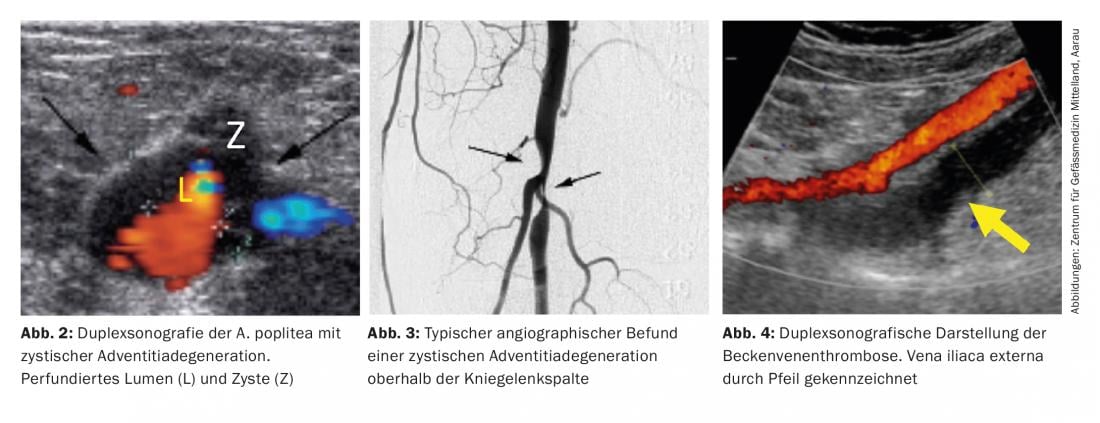

Cystic adventitia degeneration (CAD): this rare cause of symptomatic stenosis (0.1%) is an important differential diagnosis of claudication in middle-aged men without cardiovascular risk factors. The diagnosis is made by means of duplex sonography (Fig. 2) and shows the typical finding of a high-grade narrowing of the artery in non-atherosclerotic vessels (Fig. 3). The genesis is not completely known; the popliteal artery is most frequently affected [1].

Therapeutic options include surgery with vein interposition and sonographically guided drainage by puncture [2]. In rare cases, spontaneous healing may occur as a result of resorption, displacement, or extravasation of the cyst contents.

M. Bürger (thrombangiitis obliterans): This disease occurs mainly in the young male smoker. The small and medium-sized arteries of the extremities are affected by segmental thrombotic vascular occlusion. The ABI is often normal at rest, and vascular occlusions are usually more distal than the measurement point. Clinically, there is recurrent ulceration of the lower extremities or critical circulatory disturbances of the toes or, less commonly, the fingers.

Especially in cases of critical ischemia, interventional therapy is attempted before amputation of the toes or fingers [3]. Apart from absolute smoking cessation, treatment options are controversial. The use of phosphodiesterase V inhibitors partially improves the wound situation. New treatment concepts include progenitor cell therapy, immunoadsorption, endothelin receptor blockade with bosentan, and surgical sympathectomy and drug sympatholysis.

Giant cell arteritis (RZA): According to the 2012 revision of the CHCC nomenclature, RZA is defined as large-vessel vasculitis involving the aorta and its major arterial branches [4] or, in the case of cranial symptoms, involving the branches of the carotid and vertebral arteries. Clinically, the cranial form is classically dominated by bitemporally accentuated, analgesic-refractory headache, scalp tenderness, masticatory claudication, and temporal artery abnormalities (tenderness, swelling, pulseless). The ophthalmological involvement is feared: Without treatment with corticosteroids, the disease can lead to blindness. In rare cases, the extremity arteries are affected. Granulomatous inflammation of the tunica media causes stenosis in the affected area. Clinically, the resulting claudication is indistinguishable from that of arteriosclerosis. In up to 50% of cases, patients suffer from polymyalgia rheumatica and symptoms of systemic inflammation.

Stent insertion should be avoided because of the fragile nature of the vessel; in severe symptomatology, PTA with a drug-eluting balloon catheter should be considered. In most cases, the symptoms are rapidly regressed by cortisone therapy.

Rare vascular causes with normal ABI.

Claudication venosa: Less well known is venous claudication of the lower extremities. Due to venous outflow obstruction (e.g. thrombosis), claudication-like symptoms occur under stress. Since the outflow obstruction often affects the iliac veins (Fig. 4), the entire leg is usually affected. Clinically, there is a pressing, bursting pain character that persists longer after cessation of exercise than in classic PAVD-related calf claudication. In May-Thurner syndrome, the iliac sinus vein is pinched off between the dorsal promontory and the right iliac artery in the pelvis. Clinically, this results in leg swelling and – due to compression – fibrosis of the vein walls with possible pelvic vein thrombosis (stasis and endothelial lesion, especially in young women).

Therapy is anticoagulation and catheter revascularization with stent placement due to venous claudication. More rarely, atresia of the abdominal veins, which often do not become clinically apparent until young adulthood, can lead to venous outflow obstruction with corresponding symptoms.

Non-vascular causes with normal ABI.

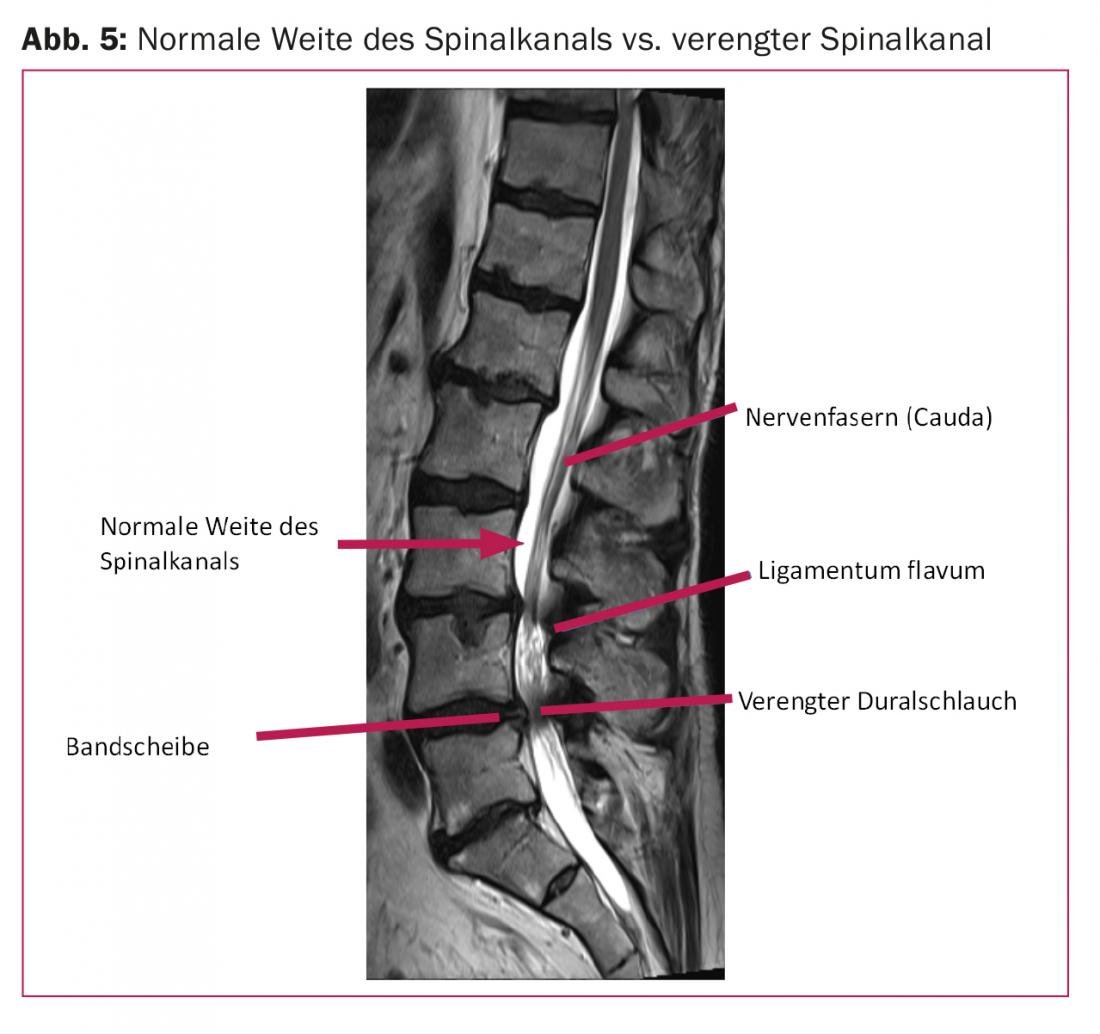

Claudication: A relatively common differential diagnosis of PAVD in daily practice is lumbar spinal stenosis. There is a mismatch between the neural structures and the space available within the spinal canal. The neural structures are compressed (Fig. 5). The cause is usually degenerative changes in the motion segments (intervertebral discs, facet joints, ligamentum flavum). The exact pathophysiological mechanisms are still the subject of controversial discussions. Clinically, spinal stenosis is usually noticeable during walking as spinal claudication (pseudoclaudication, neurogenic claudication) with rapid improvement when bending over. In contrast to PAVD, symptoms often occur under stress from gluteal pulling through the dorsal thighs to the lateral lower legs as well as feet and toes. The complaints may be unilateral or bilateral. Accompanying leg heaviness, dysesthesias, and burning pain may occur.

Physiotherapy-guided exercises to strengthen the stabilizing deep back and abdominal muscles, gait training, and lordotic exercises are the conservative approaches to therapy. Should the symptoms still progress, surgical therapy must be discussed.

Cox/Gonarthrosis: Osteoarthritis is caused by mechanical wear of the joint cartilage. The cartilage, which is becoming thinner and thinner, tears. The increase in pressure on the bone increases and osteophytes develop, leading to increased immobility of the joint. In the final stage, bone lies on bone. At the onset of the disease, clinical symptoms are present only after prolonged ambulation in the joint or even radiating into the thighs. In the advanced stage, there is characteristic pain on start-up and fatigue in the area of the affected joint. In case of gluteal complaints under stress (especially when walking uphill), a differential diagnosis of obstruction of the internal iliac artery should be considered. In the case of an isolated finding, the ABI value may also be within the normal range.

Foot deformities: The skeletal changes that accompany advancing age also occur in the foot area. In most cases, there are changes in the longitudinal arch with buckling of the flat foot (pes planusvalgus). The resulting rigid flat feet and deformities can sometimes cause pain radiating into the calf under stress. Particularly in diabetics, neuropathy leads to incorrect and excessive loading of certain regions of the foot [5]. With such changes in the static and dynamic situation of the foot, individual, orthopedically adapted insoles can often already bring about a significant reduction in complaints.

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease may, in rare cases, have a differential diagnosis of vascular foot claudication on exertion. In this case, arteriosclerotic changes in the distal arteries of the lower leg and/or small arteries of the foot are responsible for the ischemic symptoms.

Take-Home Messages

- The clinic of degenerative changes is difficult to distinguish from that of PAVD, and measurement of ABI is directional.

- However, with a normal ABI, a circulatory disturbance is not completely excluded.

- In young women with load-dependent lower extremity pain, venous claudication should be considered.

Literature:

- Levien LJ, Benn CA: Adventitial cystic disease: a unifying hypothesis. J Vasc Surg 1998; 28: 193-205.

- Do DD, Brunswick M, Baumgartner I, et al: Adventitial cystic disease of the popliteal artery: percutaneous US-guided aspiration. Radiology 1997; 203: 743-746.

- Modaghegh MS, Hafezi S: Endovascular treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s Disease). Vasc Endovascular Surg 2018; 52: 124-130.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al: 2012 revised international chapel hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 1-11.

- Rheumaliga Schweiz, ed.: Update Rheumatologie 2016 für Hausärzte. The painful foot. Efficient diagnostics – successful therapy.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(5): 17-20