Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck is rare. However, it behaves much more aggressively compared to cutaneous malignant melanoma. Corresponding leading symptoms should be the reason for a rapid ENT specialist clarification.

Mucosal melanomas are rare and account for 1% of all malignant melanomas. Half of them are found in the head and neck area. Compared to cutaneous malignant melanomas, they show a much more aggressive behavior and are more prone to regional and distant metastases. Local recurrences are also common, leading to an increased disease-specific death rate.

The peak incidence of these melanomas is between the ages of 60 and 80 . There appears to be a slight male dominance in the gender distribution here. Due to their hidden location, mucosal melanomas of the head and neck region are often diagnosed only at a locoregionally advanced stage. Lymph node metastases are seen in 5-48% of patients at diagnosis, and distant metastases in 4-14%. The nasal cavity is the most frequently affected region. Here, melanomas are usually located in the anterior portion of the nose, followed by the middle and inferior turbinates. Melanoma of the superior turbinate, olfactory groove, or ethmoid is an absolute rarity. In the oral cavity, the most commonly affected sites are the palate and gingiva. Very rarely, mucosal melanoma may be found in the pharynx, larynx, or upper esophagus. The most common location in the larynx is the supraglottic region.

The appearance of the tumor varies from macular to ulcerated or nodular to polypoid. The color varies from black to gray or pink to red. Severe pigmentation occurs in approximately 75% of oral melanomas, but only in 50% of sinunasal melanomas. In contrast to cutaneous melanoma, mucosal melanoma of the head and neck typically presents at the time of diagnosis in a more aggressive vertical growth phase with invasion of the underlying submucosa. As a consequence, the accompanying superficial horizontal extension is often missing in this case.

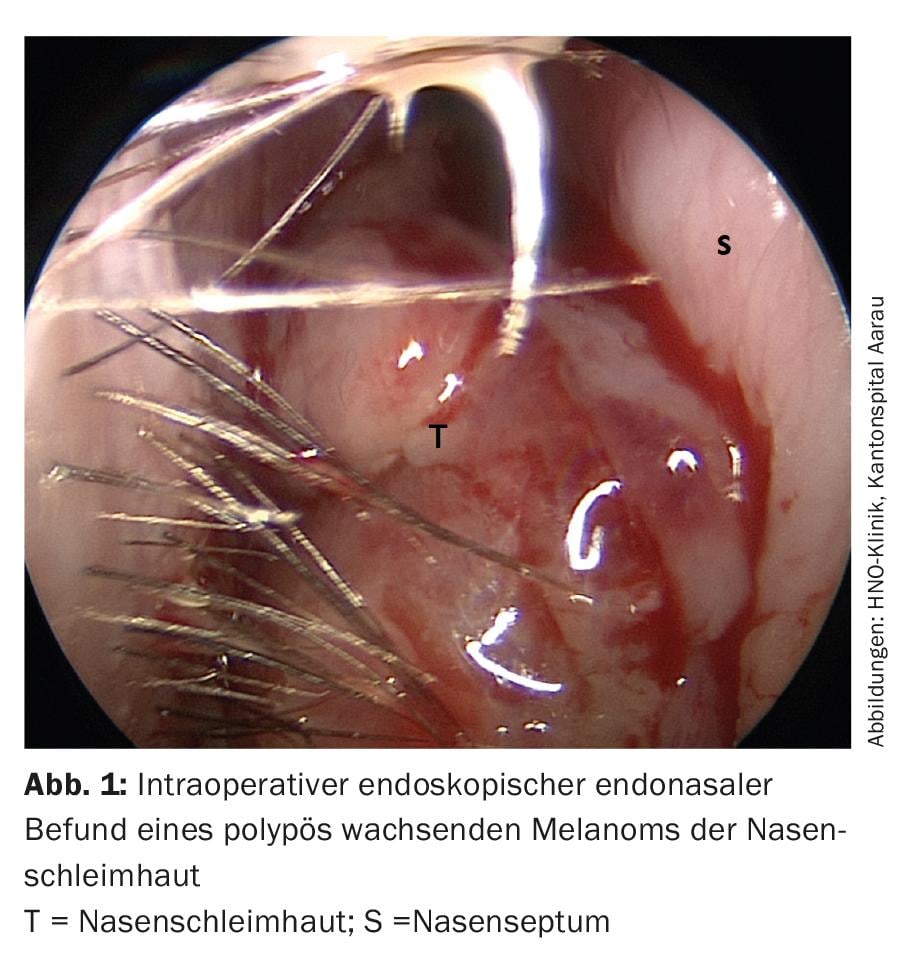

Most patients with sinunasal mucosal melanoma present with unilateral nasal obstruction, tumor mass, epistaxis, or a combination of the symptoms (Fig. 1). Rhinorrhea, epiphora, facial pain and swelling are more common in advanced cases. The predominant clinical presentation of tumors in the oral cavity is a painless mass. Ulceration and bleeding may often be present.

Diagnostics

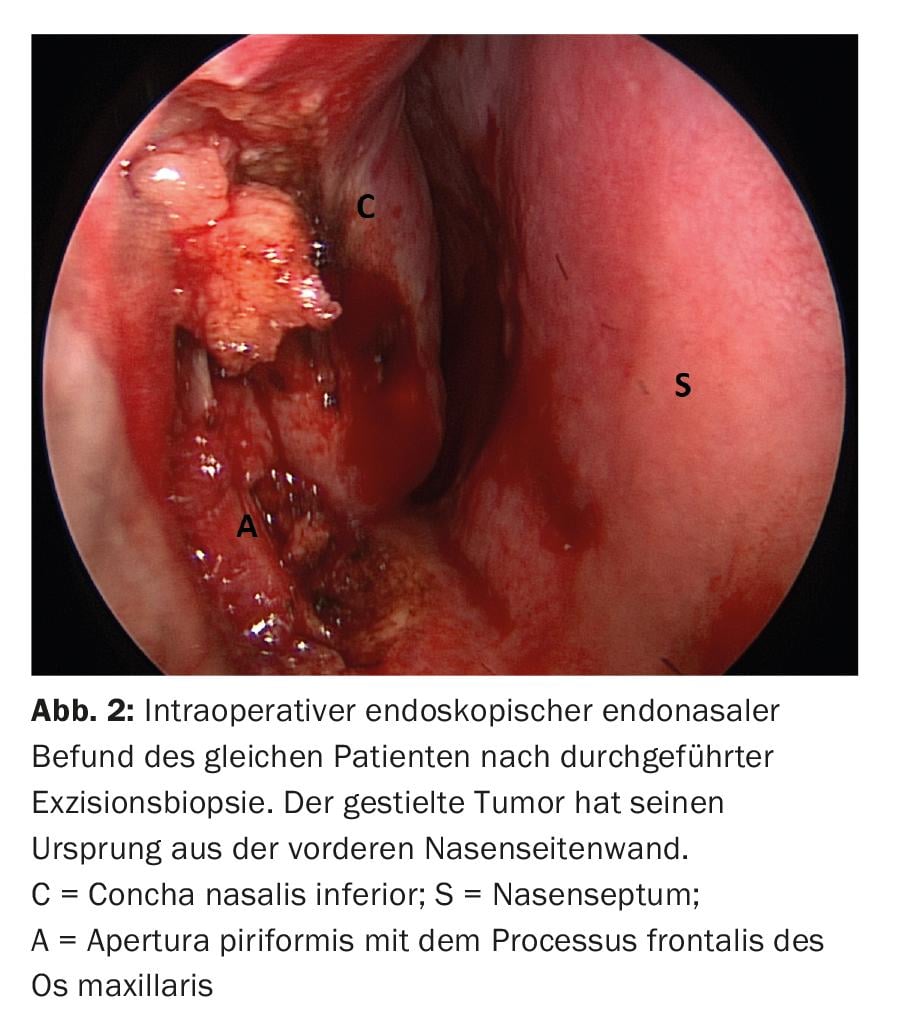

The presence of a pigmented lesion in the oral or nasal cavity should raise suspicion of mucosal melanoma, and a biopsy of the lesion should be obtained promptly (Fig. 2) . Diagnosis is dependent on the identification of intracellular melanin. Nevertheless, immunohistochemistry is often required to diagnose malignant melanoma because only 50-70% of lesions in the oral cavity have melanin. Melanomas show high positivity of the immune marker S-100, a calcium-binding protein found in neural tissues. However, this protein is present in a variety of normal and neoplastic cells. The frequency of S-100 immunoreactivity in mucosal melanomas varies from 86-100%. A reactive antigen that is more specific for melanoma cells is HBM-45 (cytoplasmic melanoma antigen). Melanoma also responds to antivimentin and NK1/C-3 antibodies, but not to antikeratin or antileukocyte antigen antibodies.

Staging

There is no universally accepted staging system for melanoma of the mucosa of the head and neck. The classic TNM classification is nevertheless frequently used. Due to the lack of histologic landmarks analogous to papillary and reticular dermis, the prognostic value of various levels of invasion as established in the Clark classification for cutaneous melanoma does not apply to mucinous melanoma. Therefore, the following three stages are often distinguished:

- Stage I: localized disease

- Stage II: regional lymph node metastases

- Stage III: distant metastases.

Imaging

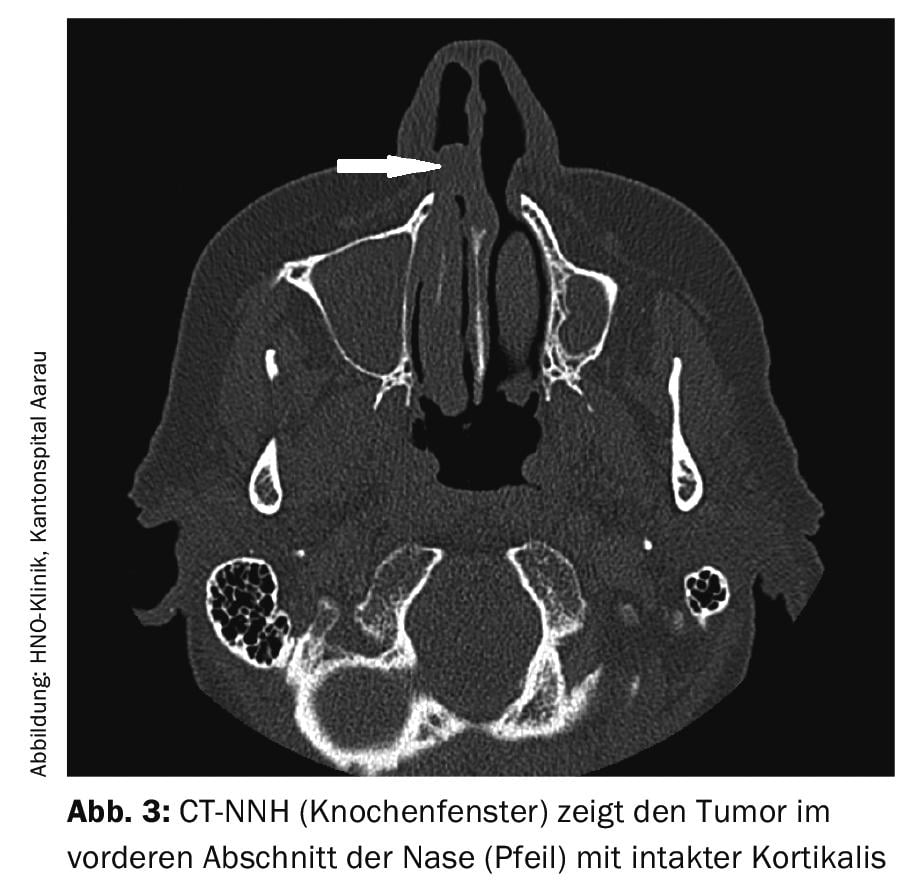

Magnetic resonance imaging is much more specific than computed tomography for the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. This is due to the paramagnetic properties of melanin. Often, the diagnosis must be supplemented by computed tomography to assess possible invasion of bony structures (Fig. 3).

Because mucosal melanoma metastasizes early regardless of the size of the primary tumor, whole-body PET/CT scanning is relevant to more accurate tumor staging.

Surgical therapy

The first-line treatment for mucosal melanoma is similar to that for cutaneous melanoma and involves complete excision with adequate margin of safety. As a result of the close proximity in the head and neck region to surrounding relevant anatomic structures, positive surgical margins are not uncommon. Nevertheless, a radical surgical approach should be pursued as long as there is complete topographic resectability and the associated morbidity appears acceptable. If regional lymph node metastases are present, “neck dissection” is indicated. In contrast, the relevance of elective neck dissection in localized tumor is still questionable. Controversy remains regarding the value of sentinel lymph node excision. This compares to cutaneous melanoma, where this technique is gaining more acceptance.

Radiotherapy

The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma is not clearly defined. Malignant melanoma has traditionally been considered relatively insensitive to radiation, yet some studies have shown a positive benefit. Numerous clinical and basic science evidences support the theory that melanoma has a high capacity for sublethal damage repair, making it resistant to conventional fractionation procedures.

Therefore, treatment with higher doses often seems more successful. Radiotherapy is usually used as an adjuvant measure, especially in cases of positive resection margins, local recurrence, or in palliation. To date, various study analyses have failed to confirm that surgery with additional radiotherapy significantly improves overall patient survival. Despite lack of significance, patients with combined therapy had the longest survival in some studies. In contrast, the addition of radiotherapy has been shown to decrease the local recurrence rate.

Chemotherapy and immunotherapy

Chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy are used in both the adjuvant setting and with palliative intent. The most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents are dacarbazine, the platinum analogues, the nitrosoureas, and the microtubular toxins.

Immunotherapy is currently effective in only a small percentage of patients with malignant melanoma. An increased response rate was observed when interleukin 2 (IL-2) and interferon-alpha (IFN-α) were used with cisplatin.

Forecast

Most recurrences occur within the first three years. Primary recurrence occurs in approximately 40% of nasal cavity lesions, 25% of oral cavity lesions, and 32% of pharyngeal lesions.

According to a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center study, clinical stage at presentation, tumor thickness >5 mm, vascular invasion on histologic examination, and development of distant metastases are the only independent predictors of overall survival. The prognostic significance of cervical or nuchal lymph node metastases is still unclear. Some studies have shown that lymph node involvement reduces median survival to 18 months. In turn, other studies showed no survival disadvantage in patients with positive regional lymph nodes compared with patients with an N0 situation.

Histologically, invasion of the lamina propria and deeper tissue is a poor prognostic factor. Likewise, the presence of sarcomatoid, pseudopapillary structures, and undifferentiated cells appears to be associated with poorer disease-specific survival.

Take-Home Messages

- Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck is a rare clinical entity, but behaves much more aggressively compared to cutaneous malignant melanomas.

- The occurrence of leading symptoms such as persistent sore throat, throat swelling or unilateral nasal discomfort should always be cause for a rapid ENT specialist clarification.

- Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment with the goal of excising the tumor as radically as possible. Adjuvant radiotherapy is becoming increasingly important, especially for local control of the disease. In addition, a clearer understanding of the biology of the disease process is leading to the implementation of new immunotherapies.

- A multicenter prospective study is needed to objectively identify better staging regimens and optimal treatment regimens for this rare entity.

Further reading:

- Bakkal FK, et al: Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: recurrence characteristics and survival outcomes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015 Nov; 120(5): 575-580.

- Warszawik-Hendzel O, et al: Melanoma of the oral cavity: pathogenesis, dermoscopy, clinical features, staging and management. J Dermatol Case Rep 2014 Sep 30; 8(3): 60-66.

- Prasad ML, et al: Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: a proposal for microstaging localized, Stage I (lymph node-negative) tumors. Cancer 2004 Apr 15; 100(8): 1657-1664.

- Saida T, et al: Histopathological characteristics of malignant melanoma affecting mucous membranes: a unifying concept of histogenesis. Pathology 2004 Oct; 36(5): 404-413.

- Christopherson K, et al: Radiation Therapy for Mucosal Melanoma of the Head and Neck. Am J Clin Oncol 2015 Feb; 38(1): 87-89.

- Temam S, et al: Postoperative radiotherapy for primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer 2005 Jan 15; 103(2): 313-319.

- Sun CZ, et al: Treatment and prognosis in sinonasal mucosal melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 65 patients from a single cancer center. Head Neck 2014 May; 36(5): 675-681.

- Heppt MV, et al: Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes in 444 patients with mucosal melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2017 Aug; 81: 36-44.

- Dreno M, et al: Sinonasal mucosal melanoma: a 44-case study and literature analysis. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2017 Sep; 134(4): 237-242.

- Song H, et al: Prognostic factors of oral mucosal melanoma: histopathological analysis in a retrospective cohort of 82 cases. Histopathology 2015 Oct; 67(4): 548-556.

- Goerres GW, et al: FDG PET for mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 2002 Feb; 112(2): 381-385.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2018; 6(1): 20-22.