A workshop at the SGIM Great Update in Interlaken dealt with the topic “Emergencies in Children”. In particular, it was about sharpening the clinical eye for impending internal medicine emergencies. Furthermore, a concise overview of the most important current therapeutic approaches for various pediatric conditions was provided.

PD Dr. med. Daniel Trachsel from the University Children’s Hospital of Basel first emphasized the importance of correctly recognizing an emergency: this includes disturbances of essential organ functions that pose an acute threat to life. Problems with brain function can be seen in alertness and spontaneous activity. Respiratory difficulties sometimes present as moans; respiratory function and rate must be examined. Disturbances in the circulation can be measured by pulse and acral skin temperature.

CNS Emergencies

The main symptoms of pediatric CNS emergencies are: reduced alertness, loss of consciousness and seizures, rarely headache and vomiting. The causes may be oxygen deprivation, epilepsy or febrile convulsions, or sepsis. In addition, hypoglycemia, trauma, infections, shock, hemorrhage and stroke, poisoning, or psychological factors such as hysteria or hyperventilation are also possible.

Possible measures are even before hospitalization:

Oxygen deficiency: clear airways, measure FiO2, bag ventilation.

Epilepsy or febrile convulsions: clear airways, antiepileptic drugs.

Hypoglycemia: blood glucose measurement

Sepsis: Give volume.

Breathing difficulties

“Most often, respiratory failure in children is based in fatigue,” Dr. Trachsel said. “The top five signs of dyspnea in infants are: Tachypnea, retraction, moaning, cyanosis, and dilation of the nostrils.”

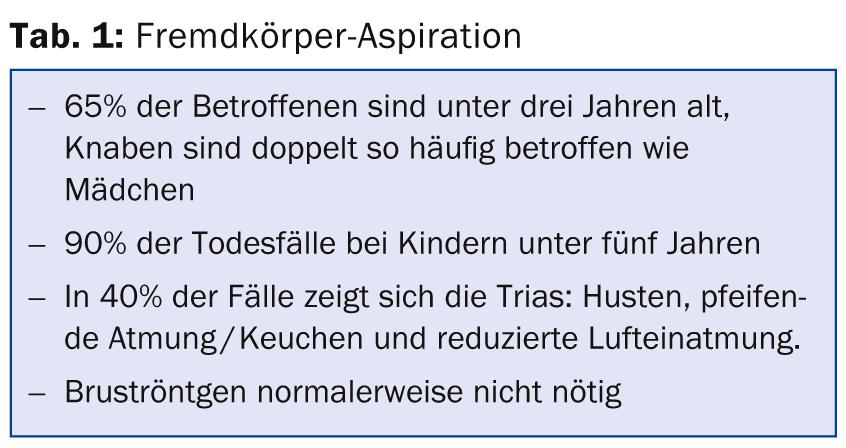

Inhaled foreign bodies: Causes of respiratory distress can be inhaled foreign bodies (tab. 1), especially with sticky sausages (Wienerli) one risks an obstruction of the airways in infants under three years of age, because they are still so small.

“A mother brings her two-year-old girl to your office, suspecting foreign body aspiration. When she arrives at your office, the girl is unconscious. What would you do? The correct answer is: briefly check the oral space for any visible foreign bodies and then immediately start resuscitation. Backslaps” or the Heimlich maneuver are not suitable immediate measures in the event of loss of consciousness. These are to be performed only when the patient is fully conscious,” Dr. Trachsel explained.

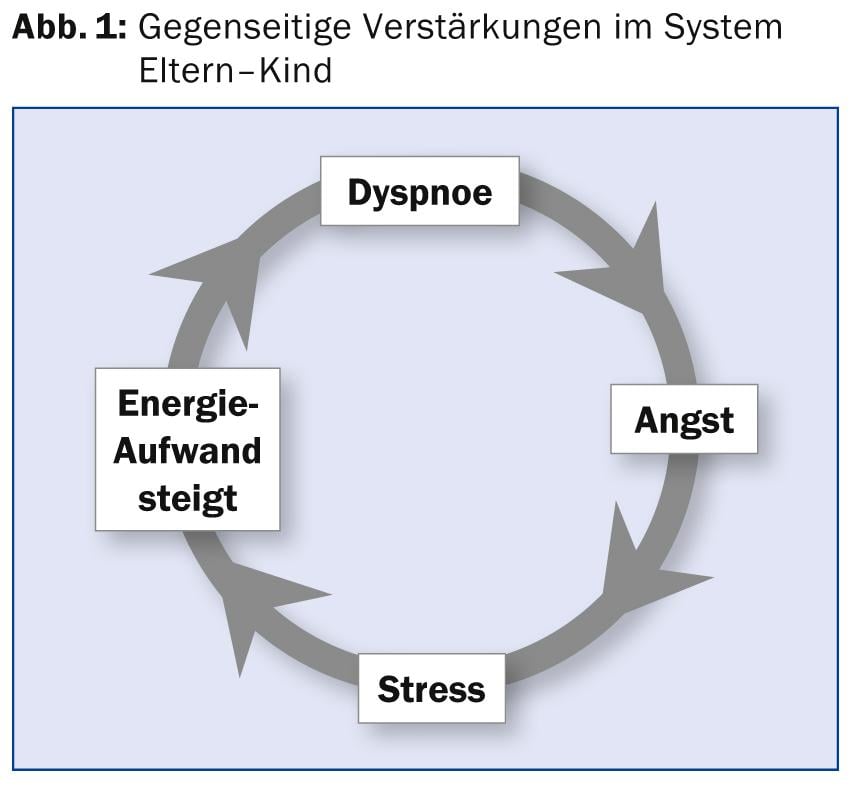

Krupp: With Krupp, the first step is to bring calm into the parent-child system. The self-propelling vicious circle must be interrupted (Fig. 1). Afterwards, humidifying measures must be taken and corticosteroids given. Step three in severe cases is inhalation with epinephrine (possibly hospitalization), step four is intubation. The antiphlogistic effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has no proven effect on the course of croup.

Febrile respiratory inflammation: “A two-year-old boy who has been suffering from a febrile respiratory infection for three days is brought to your office. Shortly before, he lost consciousness. Now he shows no spontaneous movements. What do you do? First, check for a pulse. If there is no pulse, cardiac massage with ventilation mask must be initiated immediately for two minutes,” Dr. Trachsel explained. Generally, respiratory defects precede cardiac arrest (major exception: congenital heart disease [Arrythmien]).

Septic shock

In the management of septic shock, the key word is “early goal-directed therapy”: central venous oxygen saturation (SzvO2) should be ≥70% and cardiac index between 3.3 and 6.0 l/min/m2. Adequate peripheral circulation should be sought. Controlled randomized trials have shown that SzvO2-guided therapy can reduce 28-day mortality from 39.2% to 11.8% [1].

“Early recognition and resuscitation by a primary care provider is so important because each additional hour that shock persists is associated with a twofold increase in mortality [2],” Dr. Trachsel concluded.

Source: “Emergencies in Children”, Seminar at SGIM Great Update, November 14-15, 2013, Interlaken.

Literature:

- de Oliveira CF, et al: ACCM/PALS haemodynamic support guidelines for paediatric septic shock: an outcomes comparison with and without monitoring central venous oxygen saturation. Intensive Care Med 2008 Jun; 34(6): 1065-1075. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1085-9. epub 2008 Mar 28.

- Han YY, et al: Early Reversal of Pediatric-Neonatal Septic Shock by Community Physicians Is Associated With Improved Outcome. Pediatrics 2003; 112(4): 793-799.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(1): 57-58