Multiple sclerosis (MS) does not adversely affect fertility, pregnancy, fetal development, or birth. Post partum, there is a 30% increased risk of relapse, although this depends on the relapse rate before pregnancy. During pregnancy, the relapse rate tends to be reduced. Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation and must be discontinued.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common neurological disease in young adulthood (onset of disease usually between 20 to 30 years of age) with the potential risk of future disability. More than two million people worldwide suffer from MS, and women are three to four times more likely to be affected than men. Therefore, the question of childbearing and pregnancy plays a central role in MS patients in connection with their MS. Historical views advising against pregnancy or even abortion, as well as insufficient education, have until not too long ago repeatedly led to MS patients deciding against pregnancy (or being urged to do so) despite wanting to have children. In the meantime, the exact opposite is the case: no woman is to be advised against her desire to have children for reasons related to the diagnosis of MS. Patients, on the other hand, are informed that there are no negative effects of MS on the unborn child, that the (type of) birth can be done according to the patient’s wishes and that, conversely, pregnancy has no negative effect on the further course of MS. It is even possible that the further course of MS is favorably influenced by (a) pregnancy(s).

Neuroimmunological aspects of pregnancy

In the course of pregnancy, there is also a change in the female immune status. This is due to maternal, fetal, and placental factors that lead from a cellular-dominated maternal immune response to enhanced humoral immunity during pregnancy. This “physiological immunosuppression” ensures that the fetus, which presents immunological factors foreign to the mother, is not rejected by the maternal immune system. Autoimmune diseases whose pathogenesis is predominantly due to the cellular effector apparatus of the immune system, such as MS, generally show a better course during pregnancy. In contrast, diseases dominated by a humoral immune response, such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum diseases, tend to worsen during pregnancy.

Influence of multiple sclerosis on fertility and pregnancy

MS does not generally affect a woman’s fertility. While at first glance women with MS have on average fewer children than healthy women, this is more likely due to the fact that MS patients sometimes have an altered sexuality/body perception and, on the other hand, fear that they may not be able to adequately care for their child(ren) in the future.

MS has no negative effects at all on the unborn child, pregnancy and birth. The risk of, for example, spontaneous abortion, fetal malformation, premature birth, or neurological complications during pregnancy (such as eclampsia) is definitely not increased by MS. The mode of delivery (whether spontaneous or by caesarean section) can be chosen entirely according to the woman’s wishes (or, if necessary, for obstetric reasons) – there are no fundamental restrictions here either, as with any other woman.

Influence of pregnancy on the course of multiple sclerosis

Numerous detailed studies demonstrated the significant decrease in the frequency of disease episodes during pregnancy, but also show an increase in the first three months after birth. The above-mentioned studies (but also everyday clinical experience) prove that disease relapses during pregnancy are reduced by almost 100% from trimester to trimester, which means that disease relapses during pregnancy are extremely unlikely. In addition, it could be shown that the further course of MS (annual relapse rate and degree of disability) was not negatively influenced by pregnancy, obstetric measures (for example, epidural anesthesia or caesarean section), or breastfeeding. On the contrary, women with pregnancy after the onset of their MS appear to have a lower risk of secondary chronic progressive MS progression.

However, all these positive effects are offset by an increase in inflammatory MS activity in the postpartum period: In the first three months after birth, about one third of MS patients have a new disease episode. However, after four to six months, this thrust risk reduces back to pre-pregnancy levels. It appears that the frequency of relapses before pregnancy determines the risk of relapses after birth, meaning that a relapse in the three months after birth can only be expected if the frequency of relapses was already high before pregnancy.

Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy

The initial manifestation of MS in pregnancy is very rare and the clinical presentation then does not differ from non-pregnant patients.

If MS typical symptoms occur in a pregnant woman, the usual diagnostic measures (MRI, CSF diagnostics) should be initiated. While native MRI scanning is considered a safe method in pregnancy and no adverse effects to the fetus have been demonstrated, the use of contrast agents should be discouraged. Contrast agent is placental and can thus enter the fetal blood circulation and amniotic fluid.

MS specific therapies during pregnancy

Current MS therapies can be divided into three groups: Corticosteroids to treat the acute MS relapse, the disease-modifying (immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive) interval therapies to prevent relapses and disease progression, and symptomatic therapies to improve existing MS symptoms.

Acute relapse therapy: methylprednisolone, the standard therapy for the treatment of acute MS relapses, can also be used in pregnancy according to the usual regimen (3×1000 mg methylprednisolone iv on three consecutive days).

There are no studies that have specifically investigated the treatment of pregnant MS patients with corticosteroids, however their short-term use is considered safe. So far, teratogenic effects have only been demonstrated in animal studies and the risk in humans, although not excluded, seems to be extremely low.

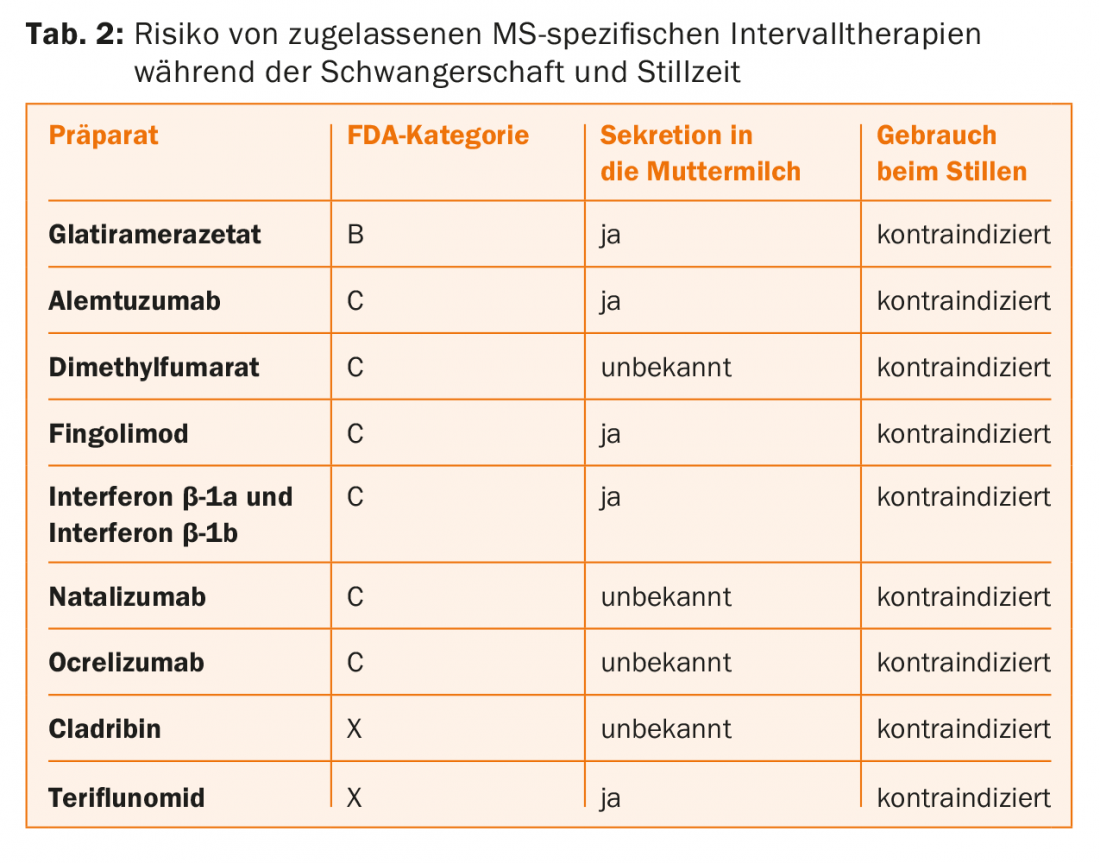

Immunomodulatory/suppressive interval therapies: According to the technical information, all interval therapies (with the exception of glatiramer acetate and natalizumab) are contraindicated in pregnancy. However, it is important for the expectant mother to know that interval therapy during pregnancy is only necessary in extremely rare exceptional cases anyway, because the pregnancy itself has a protective effect with regard to further relapses during pregnancy (see above).

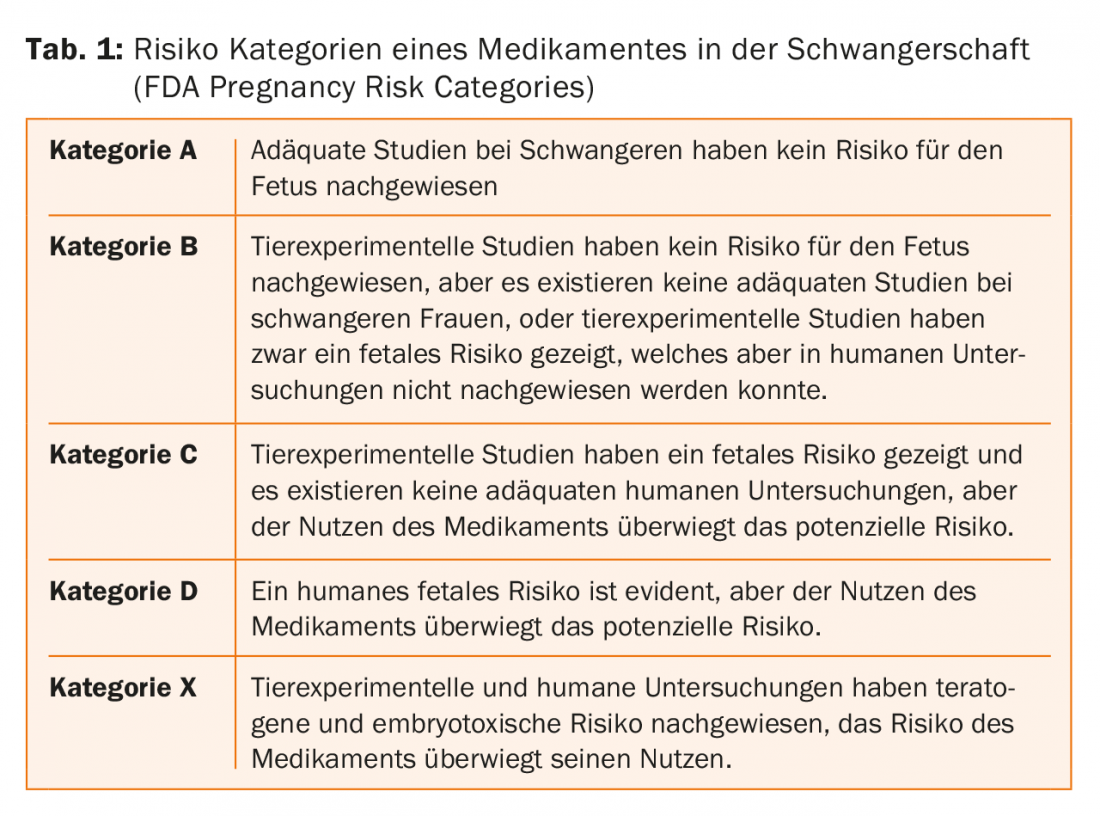

The risk of a drug to be taken during pregnancy is determined by the so-called “pregnancy risk category” of the FDA (=US Food and Drug Administration) (Tab. 1). In concrete terms, this means that some interval therapies must be terminated as soon as pregnancy is planned, while others can be given until the onset of pregnancy or, in exceptional cases, even during pregnancy. (Tab.2). This is relevant in practice because half of all pregnancies usually occur unplanned.

Based on the available data (phase II and III studies, postmarketing analyses, pregnancy and therapy registries) and the sometimes long-term clinical experience, the following approach is recommended for the approved interval therapies:

- Interferon-β preparations, glatiramer acetate, and natalizumab may be administered/taken until pregnancy occurs. Glatiramer acetate and natalizumab can also be used in pregnancy in very individual cases under appropriate risk-benefit assessment. These drugs are contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Fingolimod: effective contraception must be used during this therapy because fingolimod may cause fetal malformations/damage. If a patient on fingolimod therapy expresses a desire to have children, fingolimod must be discontinued, but contraception must be continued for an additional two months after fingolimod discontinuation. Fingolimod is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Teriflunomide: Effective contraception must be used during this therapy because teriflunomide may cause fetal malformations/damage. If an MS patient on therapy with teriflunomide plans to become pregnant or even becomes pregnant, then teriflunomide must be “washed out” with cholestyramine (3×8 g daily for 11 days) and then the plasma concentration of teriflunomide determined (a concentration <0.02 mg/L is no longer considered teratogenic). Teriflunomide is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Alemtuzumab: Women of childbearing potential must use a reliable method of contraception during the treatment period and until four months after the last infusion. Alemtuzumab is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Dimethyl fumarate: Data and experience are still limited here, so that it is currently recommended that women should already discontinue therapy with dimethyl fumarate if they are planning to become pregnant. Dimethyl fumarate is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Cladribine: Is contraindicated in pregnant women due to risk of malformation, so women must use a reliable method of contraception until at least six months after last cladribine use. Men capable of procreation must also use reliable contraception during treatment with cladribine and for at least six months after the last dose. Cladribine is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

- Ocrelizumab: Women of childbearing potential must use effective contraception during treatment with ocrelizumab and for 12 months after the last infusion. Ocrelizumab is contraindicated during the breastfeeding period.

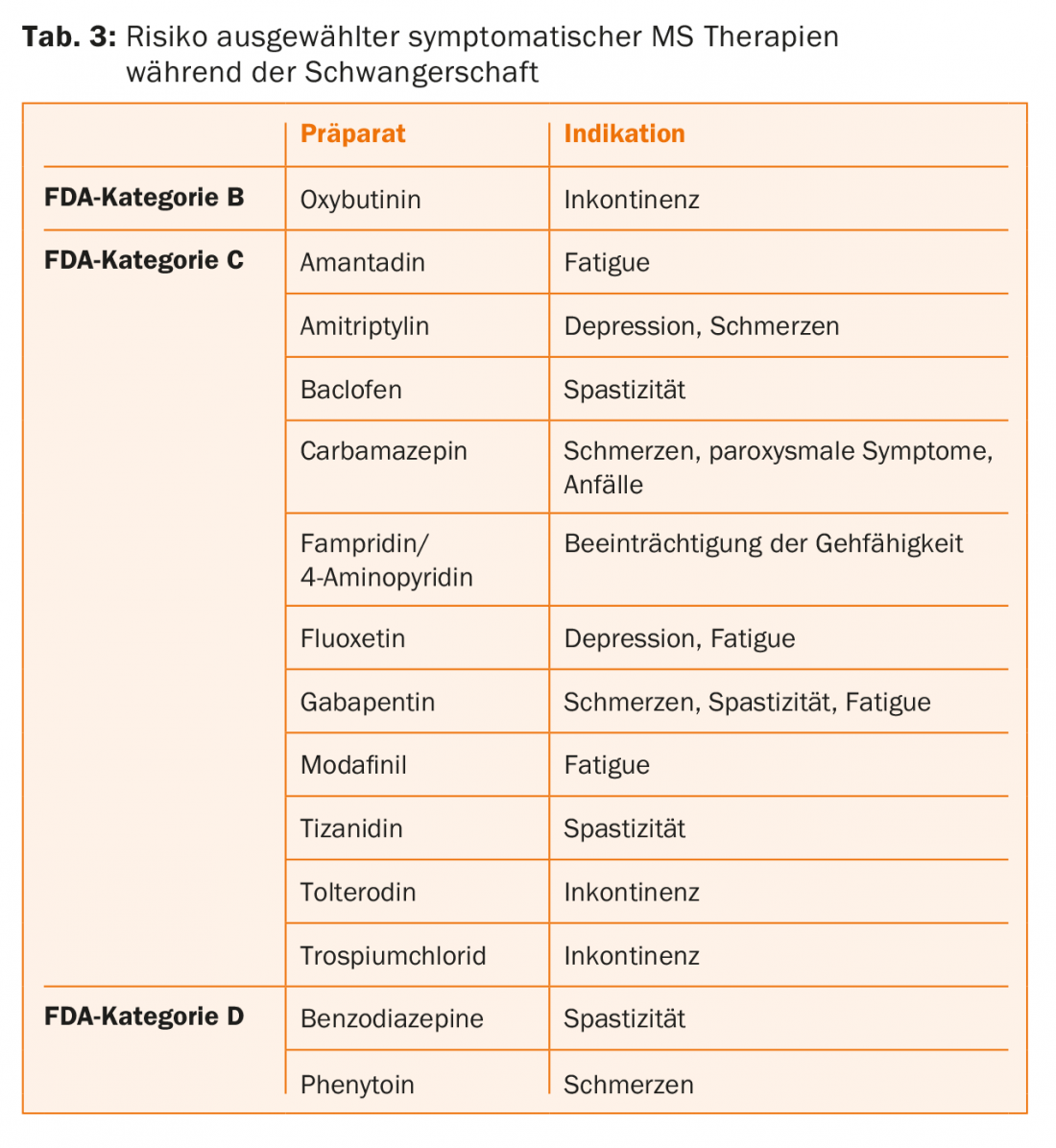

Symptomatic therapies: In addition to the disease-modifying interval therapies described above, a variety of medications are used in MS patients for symptomatic treatment of existing neurologic complaints (including spasticity, ataxia, impaired ambulation, neurogenic bladder dysfunction, fatigue, and depression). These medications should also be discontinued if pregnancy is planned or has occurred, according to their FDA risk assessment (Table 3) , and more nonpharmacologic therapies such as neurophysiotherapeutic interventions should be prescribed.

Breastfeeding

In general, MS patients should be encouraged to breastfeed their children because breastfeeding seems to have a beneficial effect on disease activity after birth. However, if a patient is not breastfeeding or has weaned, then the usual criteria for a treatment decision should be followed and immediate restart of paused therapies should be recommended. If an episode occurs during breastfeeding, then standard therapy with methylprednisolone is generally possible. However, care should be taken to separate steroid therapy and breastfeeding in time (about 3-4 hours) because corticosteroids may pass into breast milk.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulins (which are in principle safe during breastfeeding) immediately after birth as a preventive measure against the increased risk of relapses during the first three months is discussed again and again. However, since evidence of the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulins for this situation has not yet been established, this therapeutic approach cannot generally be recommended. However, in special exceptional cases, especially if a patient had a lot of relapses before pregnancy, this therapeutic option may be considered.

Education and counseling

Pregnancy issues should be fully discussed with MS patients at an early stage. When it comes to family planning, MS patients are concerned mainly because of two uncertainties: the lack of prediction about individual disease progression and concerns that pregnancy may have a negative impact on the course of MS. Here, the neurologist must provide the patient with the comprehensive information about the current state of knowledge and the basically beneficial influence of pregnancy on MS. This also includes the optimal individual therapy planning in case of a principled desire to have children. This is to ensure that an MS patient receives the best possible education and support in her most personal decision to have a child, especially to eliminate any uncertainty.

Take-Home Messages

- MS has no adverse effect on fertility, pregnancy, fetal development, or birth.

- The mode of birth, as with any other woman, can be entirely according to the patient’s wishes (or obstetric necessities, if any).

- Pregnancy has no negative impact on MS. There is a significant reduction in the relapse rate during pregnancy. The risk of MS relapse post partum seems to depend on the relapse frequency before pregnancy.

- Despite the 30% increased risk of relapse post partum, pregnancy has no negative effect on further MS disease progression.

- Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation and must be discontinued.

- Methylprednisolone may be used in the event of an episode during pregnancy.

- After the end of the breastfeeding period, the usual criteria for a therapeutic decision should be followed and the immediate restart of paused therapies is recommended.

Further reading:

- Berger T: Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy. In: Berger T, Brezinka C, Luef G (eds): Neurological diseases in pregnancy. Springer Verlag, Vienna, 2006, pp 231-51.

- Confavreux C, et al: Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group.

- N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 285-291.

- Specialty information on disease-modifying MS therapies (Aubagio®, Avonex®, Betaferon®, Copaxone®, Gilenya®, Lemtrada®, Mavenclad®, Ocrevus®, Plegridy®, Rebif®, Tecfidera®, Tysabri®).

- Gold SM, Voskuhl RR: Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol 2016; 38: 709-718.

- Reich DS, et al: Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 169-180.

- Vaughn C, et al: An Update on the Use of Disease-Modifying Therapy in Pregnant Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2018; 32: 161-178.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(5): 38-41.