Seasonal flu vaccination is the most effective, easiest and least expensive prevention. However, the effectiveness is suboptimal in people with weakened immune systems. Therefore, they rely on indirect protection from fellow vaccinated individuals.

Every winter, the wave of influenza can surprise us by the moment of its outbreak, its intensity and its effects. Variability depends, among other things, on the virulence of circulating influenza strains, preexisting immunity in different age groups, vaccination coverage, and the match between antigens in the vaccine and circulating viruses. In Switzerland, influenza leads to 109,000 to 275,000 physician consultations annually (and, according to the Sentinella reporting system [1], to several thousand hospitalizations [2] and hundreds of deaths). Children usually contract the disease most frequently, whereas approximately 90% of deaths affect the elderly [3]. Healthcare workers are at higher risk of contracting influenza in the course of their work, and absenteeism places an additional burden on the team (of practices, hospital departments, homes, or Spitex organizations) [4].

In 42 countries in Europe, influenza A viruses predominated in 87% of 2000-2015 (417 influenza epidemics), and influenza B predominated in 13%. The flu wave seems to spread mostly from Great Britain and Southern Europe towards Eastern and Northern Europe. In Switzerland, the peak of influenza A-dominated influenza waves is on average in February (towards the end of the month), and for influenza B in March (beginning of the month). However, the temporal variability is large [5].

Influenza subtype A(H3N2) tends to cause somewhat more severe courses of illness than subtype A(H1N1), particularly in the elderly. In contrast, influenza type B tends to be milder but affects children somewhat more frequently [6].

The most important and common complications of influenza disease are primary or (more commonly) secondary bacterial infections of the throat, nose, and ears, and pneumonia, often caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Staphylococcus aureus. Primary viral influenza pneumonia is very rare, but it has a high lethality. During the 2016/2017 influenza season, pneumonia occurred in 4.3% of all reported suspected influenza cases, and this proportion was 14.3% in those aged 64 years and older [7]. Other complications include exacerbation of (chronic) respiratory or other underlying diseases, myocarditis, and CNS disorders (e.g., encephalitis or Guillain-Barré syndrome). More often affected by a severe course of the disease and complications are people with a weakened immune system: seniors, pregnant women, infants (especially premature babies) and patients with chronic diseases. Especially in the elderly, the consequences of influenza can lead to a significant loss of autonomy and occasionally, directly or indirectly, to death.

The seasonal flu vaccination

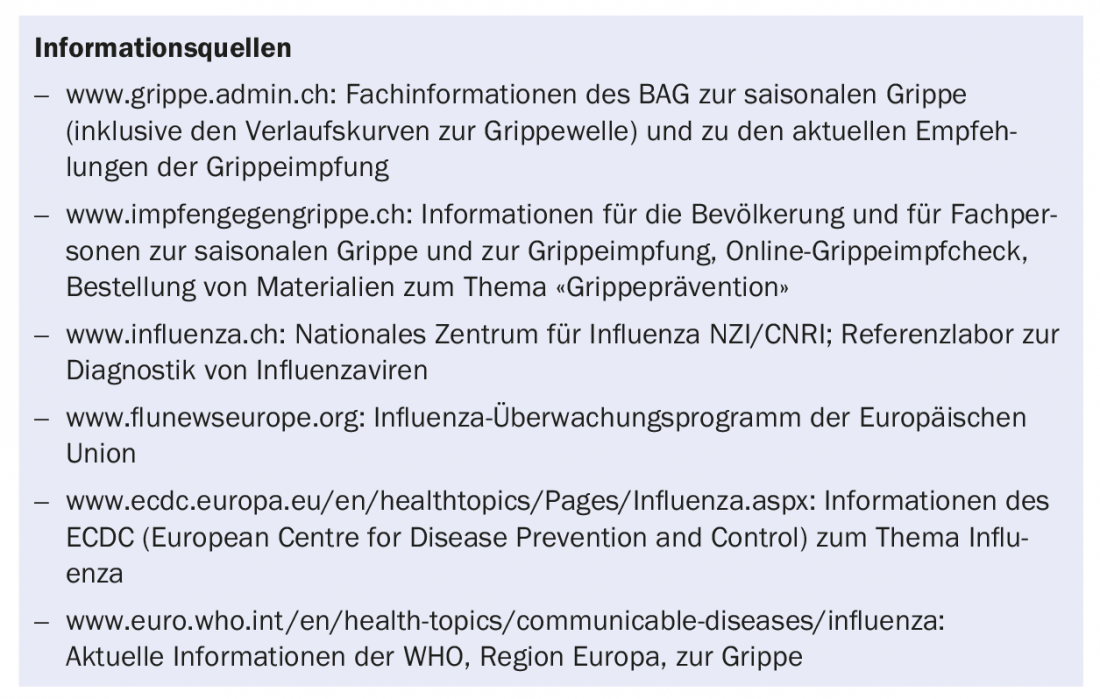

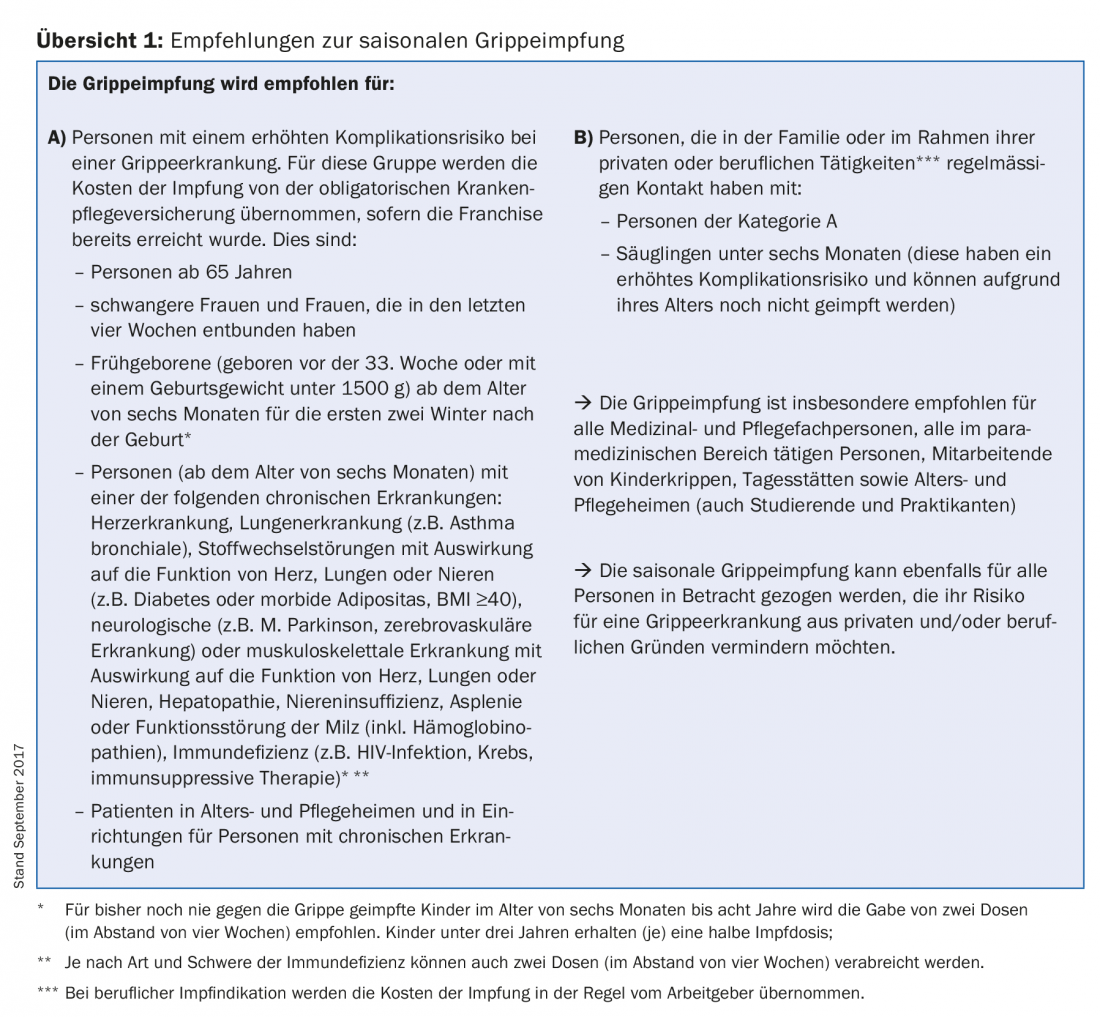

The recommendations for seasonal influenza vaccination have remained unchanged since 2013 (overview 1). Since then, it has been recommended for pregnant women not only during the second or third trimester, but throughout pregnancy. The flu shot is safe and it helps protect expectant mothers and their children from flu complications.

Efficacy in protecting against influenza illness is usually between 50% and 90% in healthy young adults. In comparison, it is sometimes significantly lower in older people and in people with a weakened immune system [8,9]. Vaccination is therefore also recommended for their close contacts in the private and professional environment, which can reduce the risk of transmission [9,10]. According to estimates, in the 2016/2017 influenza season, which was dominated by influenza strain A(H3N2), vaccination protected approximately 38-48% of all vaccinated individuals-including those with compromised immune systems-from becoming ill [7].

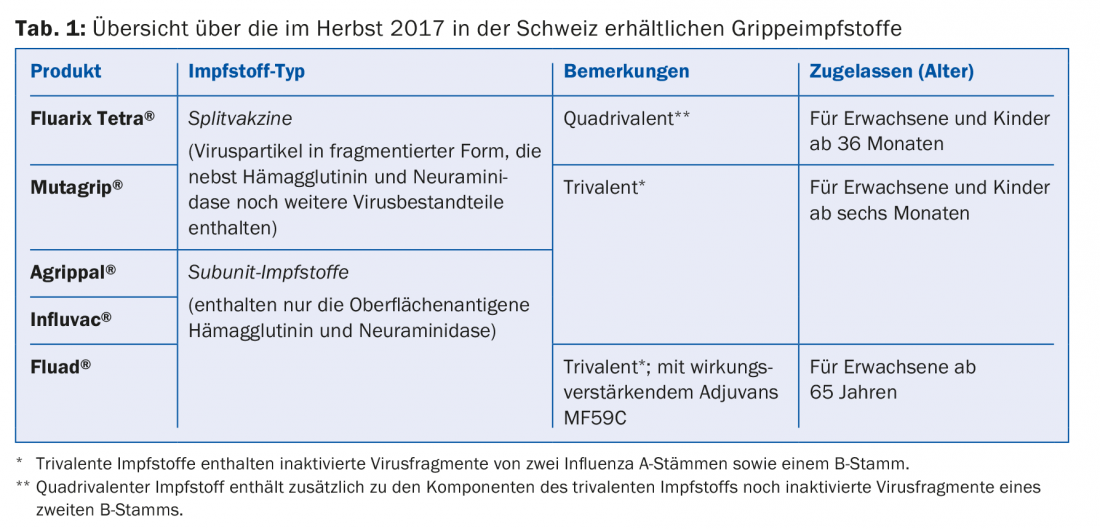

Ideally, the flu vaccination is given between mid-October and mid-November. But even after that, depending on your personal situation (state of health, pregnancy, etc.), it may make sense to catch up on a missed vaccination (if possible) before or shortly after the start of the flu season. Traditionally, seasonal influenza vaccines are produced using chicken egg culture, they are inactivated, i.e. they cannot cause influenza themselves, and they are free of mercury and aluminum compounds. Table 1 provides an overview of the influenza vaccines available in Switzerland.

Adverse inoculation reactions (UIE): The most common is a local reaction at the injection site in 10-40% of cases, which resolves after a few hours or a maximum of two days without therapy. General symptoms such as fever, malaise, muscle pain, joint pain, and headache are seen in 5-10% of those vaccinated. Severe allergic reactions such as angioedema, asthma, or anaphylaxis are very rare (<1/10,000) and usually due to hypersensitivity to chicken egg proteins. Therefore, vaccination is not recommended in cases of known severe allergy to chicken egg. Neurological manifestations are extremely rare, e.g. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) – the latter is found in about one person per million vaccinated, although a causal relationship is unclear [9].

Flu prevention support

The FOPH provides healthcare professionals with a wide range of information and training materials for influenza prevention in healthcare facilities and for patient information. Various information materials can be ordered free of charge (www.bundespublikationen.admin.ch, search term “flu”).

Under the auspices of the College of Family Medicine (KHM) and with the support of the FOPH, primary care physician organizations held the 14th National Influenza Vaccination Day on Friday, November 3, 2017. On this campaign day, the approximately 1,600 participating medical practices throughout Switzerland each offer the population the opportunity to be vaccinated against influenza for the recommended flat rate of 30 Swiss francs and without advance notification. Detailed information and addresses of participating physician practices can be found on the KHM website.

Implementation of the National Strategy for the Prevention of Seasonal Influenza (GRIPS).

The FOPH, the cantons, and numerous other health care stakeholders have been involved in influenza prevention and vaccination promotion for several decades. However, the disease is still often mistaken for a simple cold, and vaccination coverage is below target for most vaccination recommendation audiences. In a representative telephone survey conducted in March 2017 with a total of 2669 respondents, vaccination coverage was 32% among persons 64 years and older, 29% among persons with chronic conditions, and 25% among health professionals. Ideally, influenza vaccination should become an annual routine for persons at increased risk of complications and their close environment.

However, the evaluation of the last influenza vaccination promotion strategy (2008-2012) also made clear that dissemination of the core messages is best achieved through multipliers (physicians, cantonal authorities, mass media, companies, etc.). The FOPH’s information material achieved a high level of awareness, was considered useful and credible by influenza prevention multipliers, and was disseminated to target groups.

The current National Strategy for the Prevention of Seasonal Influenza (GRIPS) aims to optimize and complement existing influenza prevention measures at the national, cantonal and institutional levels. In addition, the implementation of GRIPS will provide a basis for better assessing the disease burden of influenza (complications, hospitalizations, deaths) on the one hand, and the benefits and cost-effectiveness of various prevention measures on the other. Based on these findings, target-oriented prevention measures will be derived. GRIPS focuses on the following three areas of action:

- Public health research (public health).

- Patient Protection

- Promotion of prevention measures.

The overarching goal is to reduce the severe illness caused by seasonal influenza, especially in those at increased risk of complications. Currently, GRIPS is being implemented by the FOPH, the cantons and the stakeholders involved. The latest implementation information can be found at www.bag.admin.ch/grips-de.

Take-Home Messages

- The primary goal of seasonal influenza vaccination is to reduce severe influenza complications, especially in people with

- weakened immune system and thus increased risk of complications, hospitalization and death. Especially in these, the effectiveness of vaccination is also suboptimal. Therefore, they are particularly dependent on indirect protection from their vaccinated peers.

- The current recommendations have been in place since 2013. Seasonal flu vaccination remains the most effective, easiest and least expensive prevention. Especially in healthcare facilities, but also outside, many infections can be prevented.

- To reduce severe influenza cases, improve vaccination coverage in target populations, and provide additional data on the burden of disease, the federal government, cantons, and national stakeholders are currently implementing the National Strategy for the Prevention of Seasonal Influenza (GRIPS).

- The FOPH provides information material for patients, relatives and practices.

Literature:

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH): Sentinella reporting system. 2017. www.bag.admin.ch/sentinella

- Cloetta J, et al: Influenza surveillance in Switzerland. Social and Preventive Medicine SPM 1997; 42(Suppl 2): S88-S91.

- Brinkhof M, et al: Influenza-attributable mortality among the elderly in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2006; 136(19-20): 302-309.

- Burls A, et al: Vaccinating healthcare workers against influenza to protect the vulnerable – is it a good use of healthcare resources? A systematic review of the evidence and an economic evaluation. Vaccine 2006; 24(19): 4212-4221.

- Caini S, et al: The spatiotemporal characteristics of influenza A and B in the WHO European Region: can one define influenza transmission zones in Europe? Eurosurveillance 2017; 22(35). DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.35.30606.

- Hamborsky J, et al: Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. (The Pink Book). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.13th edition. 2015. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH): Seasonal report on influenza 2016/2017. FOPH Bulletin 2017; 31. www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/service/publikationen/bag-bulletin.html

- Kelly HA, Valenciano M: Estimating the effect of influenza vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2012 Jan; 12(1): 5-6.

- World Health Organization (WHO): Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012 Nov 23; 87(47): 461-476.

- Pagani L, et al: Transmission and effect of multiple clusters of seasonal influenza in a Swiss geriatric hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2015; 63(4): 739-744.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(11): 16-20