If the formation of new blood cells in the bone marrow is disturbed, a rare form of chronic blood cancer may be the cause. Hyperproliferation of the three cell series in the bone marrow causes erythrocytosis, thrombocytosis, and leukocytosis in polycythaemia vera. The result is, among other things, a significant increase in hematocrit levels and thus also in the risk of thromboembolic events.

Polycythaemia vera (PV) is a very rare, chronic myeloproliferative neoplasia and is characterized by increased hematopoiesis. The majority of PV patients have a mutation in the JAK2 tyrosine kinase gene [1]. It results in increased cell proliferation as well as increased production of proinflammatory cytokines. The overproduction of erythrocytes and consequently increased hematocrit levels increase blood viscosity. In this way, the occurrence of thromboembolism is favored: 45% of all deaths in PV are due to thromboembolic complications [2]. However, the prognosis is generally favorable. The median age at diagnosis is 65 years.

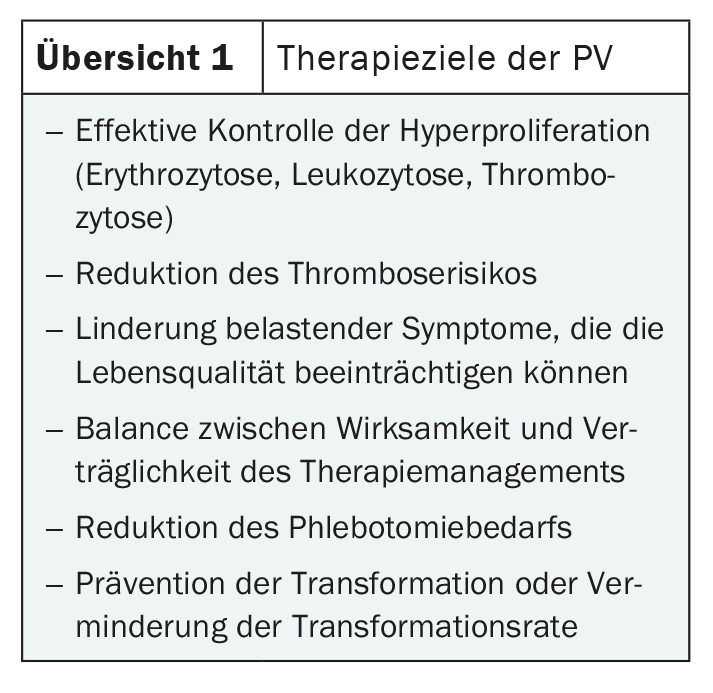

Although the symptoms are varied, they are generally rather unspecific. Therefore, the diagnosis is often made only by chance. Possible symptoms include headache, visual disturbances, fatigue and pruritus, as well as bone pain and pain in the upper abdomen. These are often caused by splenomegaly typical of PV [1,2]. The increased blood cell mass can cause circulatory disorders, which can lead to severe venous and arterial thromboses such as pulmonary embolism, apoplexy or myocardial infarction. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are therefore indicated (Overview 1) [3].

In the chronic phase, which usually lasts for years, the focus is on the clinical features of increased myeloproliferation. The most frequent and potentially threatening complications are arterial or venous thromboembolism in up to 40% of patients. In the late phase of the disease, the main problem lies in a so-called ‘delayed’ phase. This is characterized by a decrease in erythrocytosis and an increase in splenomegaly, associated with fibrosis of the bone marrow, which may be followed by transformation into (secondary) post-PV myelofibrosis and/or acute leukaemia [1]. The overall rate of post-PV-MF is around 15% after a median observation period of 10 years and 50% after 20 years.

Risk-adapted treatment

Because prevention of thromboembolism is paramount, phlebotomy is often considered the treatment of choice. This can lower the hematocrit (Hct) to below 45% and reduce the hyperviscosity of the blood. Studies have shown that setting Hct below 45% can reduce the rate of cardiovascular death in PV to one quarter [4]. However, a phlebotomy is very tiring. Treatment with low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) should therefore also be initiated initially. The treatment recommendation is then based on the risk score. A low risk can be assumed for younger patients <60 years of age who have not previously had a thrombosis. It is currently being discussed whether cytokine-reducing treatment should also be considered for them under certain conditions.

However, the majority of PV patients are at high risk anyway. In them, initiation of cytoreductive therapy is indicated. Hydroxyurea (HU) or interferon alpha (INF) are recommended for primary treatment [5]. However, HU in particular is not suitable for all patients and can cause serious side effects (Overview 2) [6]. Therefore, INF is more commonly used in younger patients of childbearing potential. If first-line therapy is not tolerated or clinical symptoms do not resolve sufficiently, treatment should be switched. The JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib has been shown in trials to control increased myeloproliferation while being well tolerated [1]. Many PV-associated symptoms, such as fatigue and pruritus, also regressed. In addition, the effect occurred very quickly in most patients, within the first four weeks. Busulfan can be used as an alternative therapy in patients of advanced age. However, the leukemogenic potential of this substance is always under discussion, which is why it should only be used with restraint. Anagrelide may be considered as a combination partner to, for example, HU or INF. This is aimed exclusively at reducing platelet production and can act as a supplement if satisfactory results are not achieved with the other substances alone.

Literature:

- www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/polycythaemia-vera-pv/@@guideline/html/index.html (last call on 23.04.2024).

- Vannucchi AM, et al.: N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 426–435.

- Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV: Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, andemerging treatment options. Ann Hematol 2014; 93: 1965–1976.

- Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et et al.: Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 22–33.

- Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al.: Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European Leukemia Net. Leukemia 2018; 32: 1057–1069.

- Barosi G, Birgegard G, Finazzi G, et al.: A unified definition of clinical resistance and intolerance to hydroxycarbamide in polycythaemia vera and primary myelofibrosis: results of a European LeukemiaNet (ELN) consensus process. Br J Haematol 2010; 148: 961–963.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2024; 12(2): 38