Changes in bowel habits, abdominal pain, bloating, stomach burning, and dysphagia are common complaints that patients see their primary care physician about, often leading to referral to a gastroenterologist. Challenges in the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders include the nonspecific nature of symptoms, no definitive diagnosis by standard testing, and lack of specific treatment options. A structured, evidence-based approach to the management of patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms is recommended.

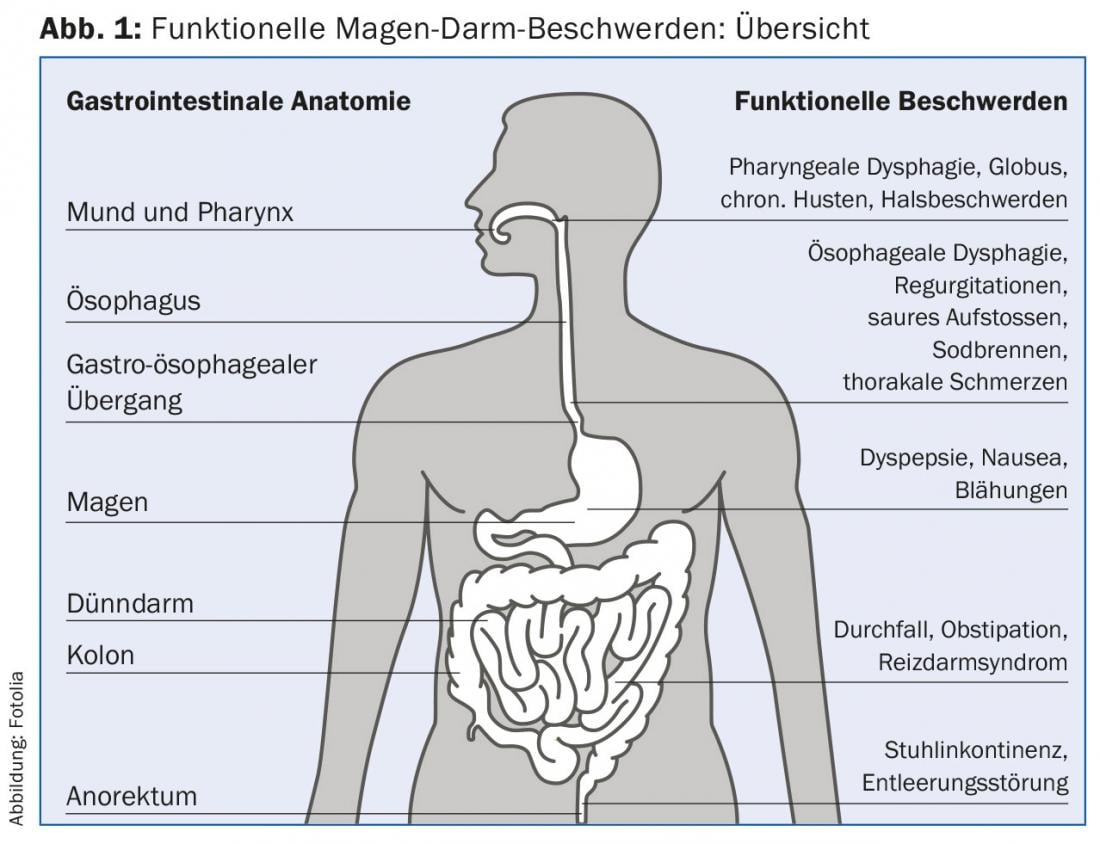

From the moment a bolus of food is swallowed to the moment it is excreted, symptoms of impaired gastrointestinal function may develop (Fig. 1) .

Dysphagia, stomach burning, abdominal bloating, abdominal pain, and changing stool consistency and frequency are very common. A recently published survey shows a prevalence of 5-15% in Europe for gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, and irritable bowel syndrome [1]. It is therefore not surprising that “functional gastrointestinal symptoms” very often lead to consultations with the family doctor and then to referrals to the gastroenterologist. Investigation and treatment of these conditions contribute to high health care costs [2]. Restricted work performance and sick days cause costs for the patient and society. Although the life expectancy of affected patients is normal [3], their quality of life may be as limited by these complaints as in a patient with heart failure or tumor disease [4].

The first part of this review outlines a structured approach to examining patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. In the second part the possibilities of a specialized clarification of patients are presented, in whom with routine clarifications no cause of the symptoms could be found.

Clarification for functional gastrointestinal complaints

Functional gastrointestinal disorders are defined according to the Rome III criteria by gastrointestinal symptoms for at least three months during the six months preceding diagnosis and without demonstrable organic pathology [5]. Depending on the question, tumor diseases, gallstones, peptic diseases, celiac disease, colitis, etc. are ruled out by means of endoscopy, imaging procedures and laboratory tests. Patients with mild symptoms and negative test results can often be treated well with simple measures (e.g., acid suppression, stool regulation with swellable fibers). In particular, the certainty that no serious disease is present should not be underestimated in its importance for the development of symptoms. For patients with persistent symptoms despite therapy, the exclusion of serious diseases is not sufficient. A specialized clarification in a functional laboratory is necessary in such cases.

The goals of these specialized examinations are etiologic clarification of symptoms and definitive diagnosis as a basis for rational and effective treatment. In the past, medical technology options for assessing gastrointestinal motility and function were very limited. Therefore, only patients with clinical suspicion of severe motility disorder (achalasia), with severe reflux disease, or with regard to surgical remediation of fecal incontinence were further specifically evaluated. Even in these patients, diagnoses were often more subjective, based on clinical presentation rather than the result of objective examinations [6].

New technologies such as high-resolution manometry (HRM) improve the accuracy and clinical utility of physiological measurements. The use of these technologies in situations close to everyday life (e.g., during a test meal) shows the investigator whether gastrointestinal events (contractions, reflux, gas production) are related to patient symptoms.

Initial assessment

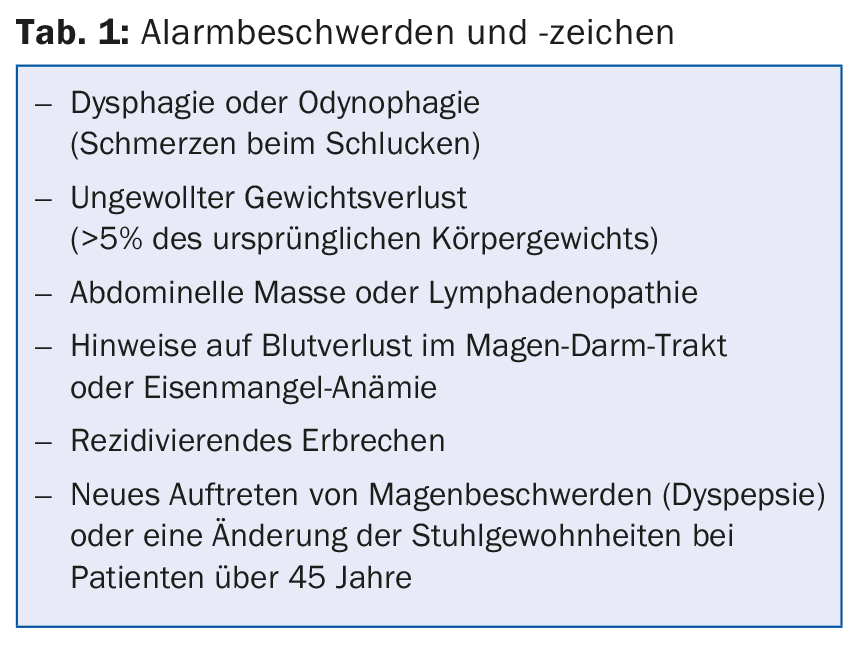

In the initial evaluation of a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms, it is important to look for alarm signs such as dysphagia or weight loss as a possible indication of neoplasia, ulcer disease or inflammatory bowel disease (Tab. 1). If alarm signs are present, the first step is to perform an endoscopy or imaging procedure. Prospective studies and meta-analyses show that alarm signs are associated with serious illness in 5-10%, compared with a 1-2% risk in patients without these symptoms [7,8].

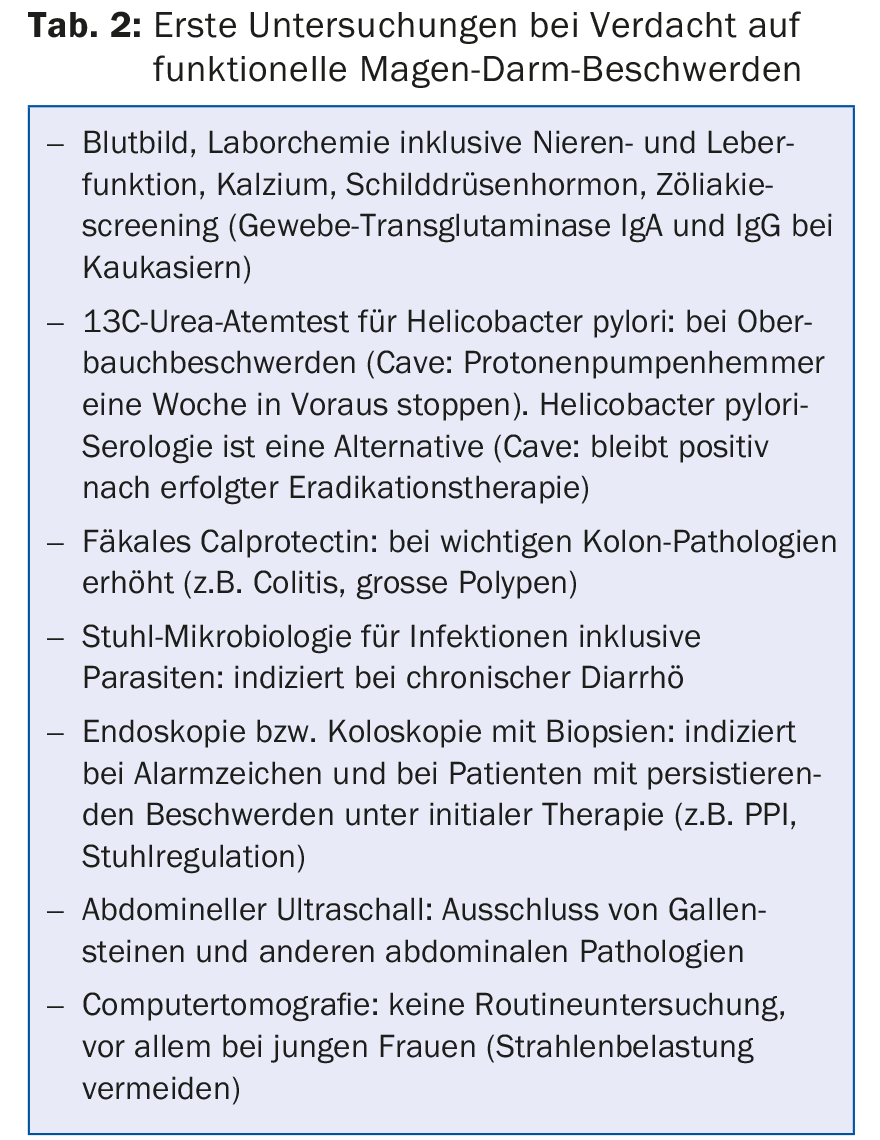

If there are no signs of possible serious disease, invasive investigations are not mandatory [9,10]. In this case, the diagnosis of functional GI disease can be made based on the clinical presentation and negative laboratory results (Table 2).

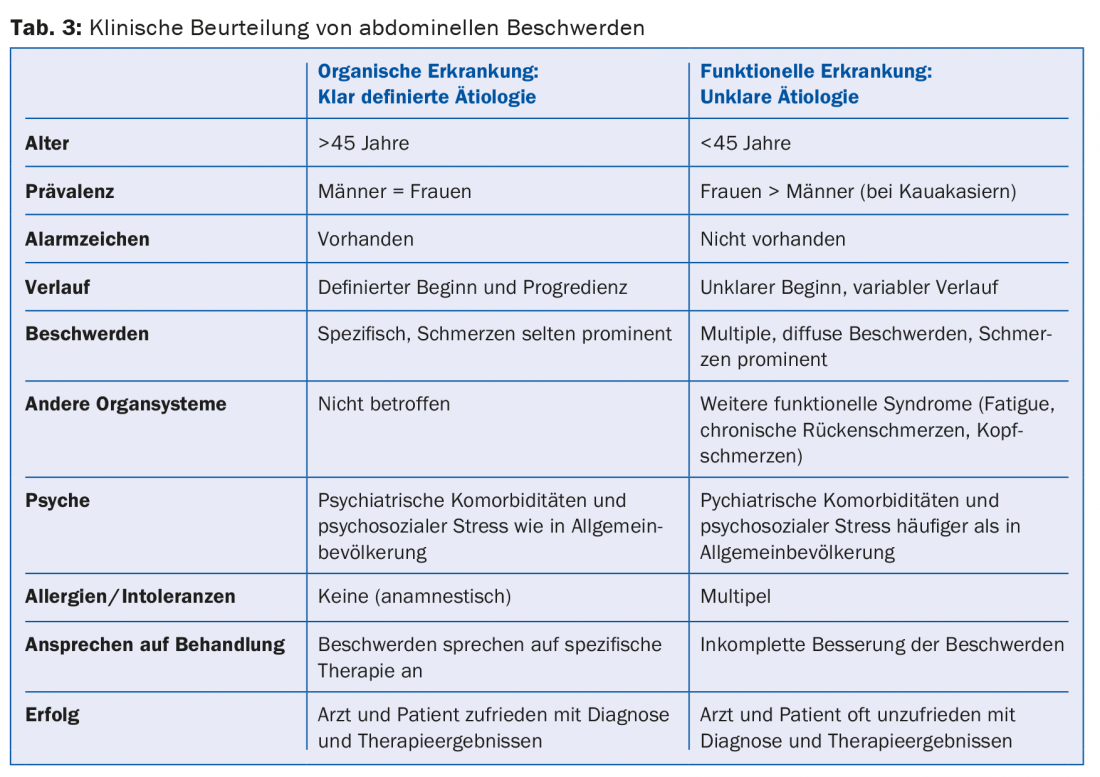

Several clues help to distinguish between organic and functional diseases (tab. 3). In an organic etiology, symptoms are stable or progressive over time, whereas in a functional etiology, patients often complain of multiple and changing symptoms. Patients with functional bowel disease suffer in up to 50% from a psychiatric disorder such as anxiety, depression or somatization. In patients with organic diseases (e.g. colitis) it is about 20%, in the whole population about 10% [13,14]. Furthermore, psychosocial stressors are often associated with a pronounced complaint pattern, inability to work and non-response to specific therapies [15]. Questionnaires are very helpful in this context to ensure that clinically relevant psychopathology is identified and treated early.

Empirical therapy

If, after initial assessment, dysfunction is considered the most likely cause of the complaints, this must be communicated to the patient. If a severe motility disorder (e.g., achalasia) is suspected, referral to a GI function laboratory is indicated. In other cases, empiric therapy is appropriate before further investigation is performed. For reflux symptoms and peptic symptoms, a therapeutic trial of proton pump blockers, administered twice daily, is reasonable [9,10]. Meta-analyses demonstrate that acid suppression may be helpful for reflux and dyspeptic symptoms (e.g., omeprazole combined with alginates or antacids for breakthrough symptoms). Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori (if present) is also useful, but the effectiveness is rather low (about 10% better than placebo) [18].

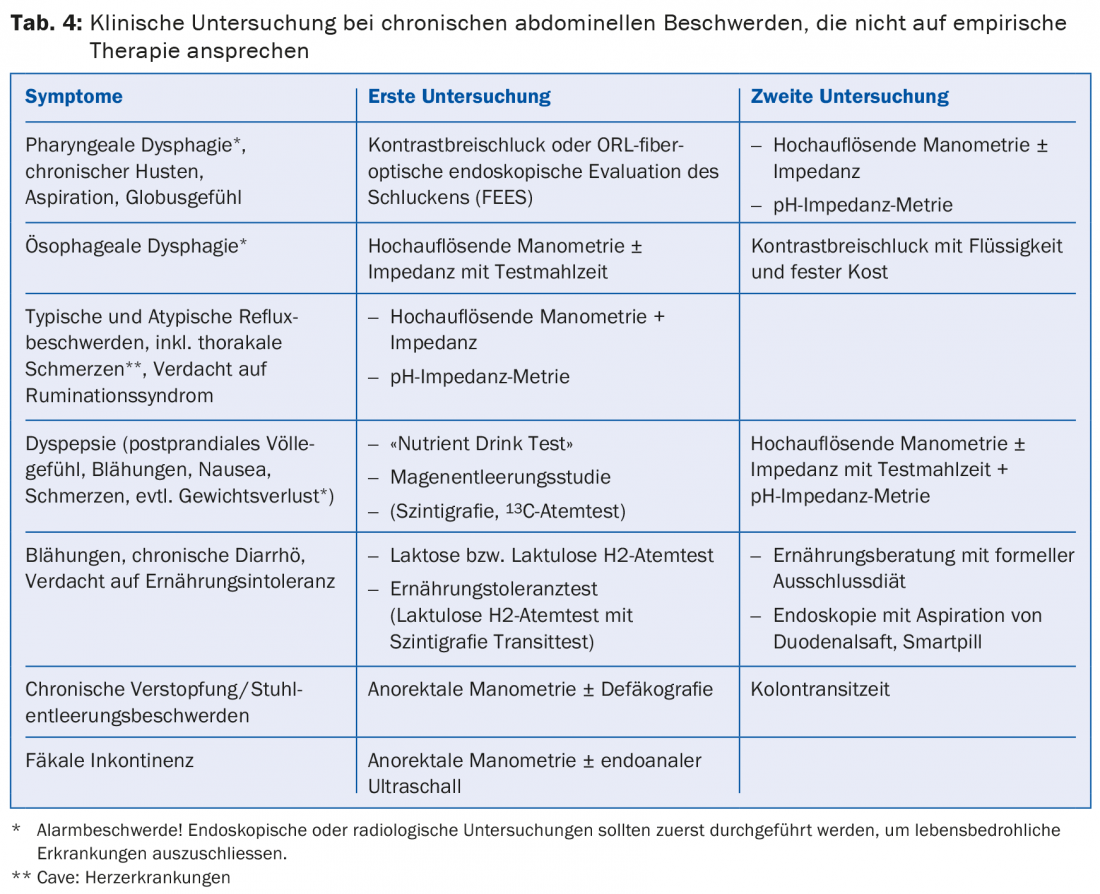

In patients with colorectal symptoms, empirical therapy with antispasmolytics and stool regulation with dietary fiber (e.g., psyllium) is performed. Medications that regulate stool frequency and consistency (e.g., loperamide, polyethylene glycol) may be additionally administered [19]. Low-dose antidepressants (e.g., amitryptiline, mirtazapine, citalopram) are often effective for functional GI symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, and visceral hypersensitivity [20–22]. If psychiatric comorbidity is suspected, referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist is recommended. If these initial strategies fail, therapies such as nutritional counseling and physical therapy should be considered. If these measures do not lead to an improvement of the complaints, a referral to the functional laboratory is indicated in order to determine clinically relevant pathologies and thus enable a targeted therapy. (Tab.4).

Part 2 in the next issue

Literature list at the publisher

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(11): 31-34