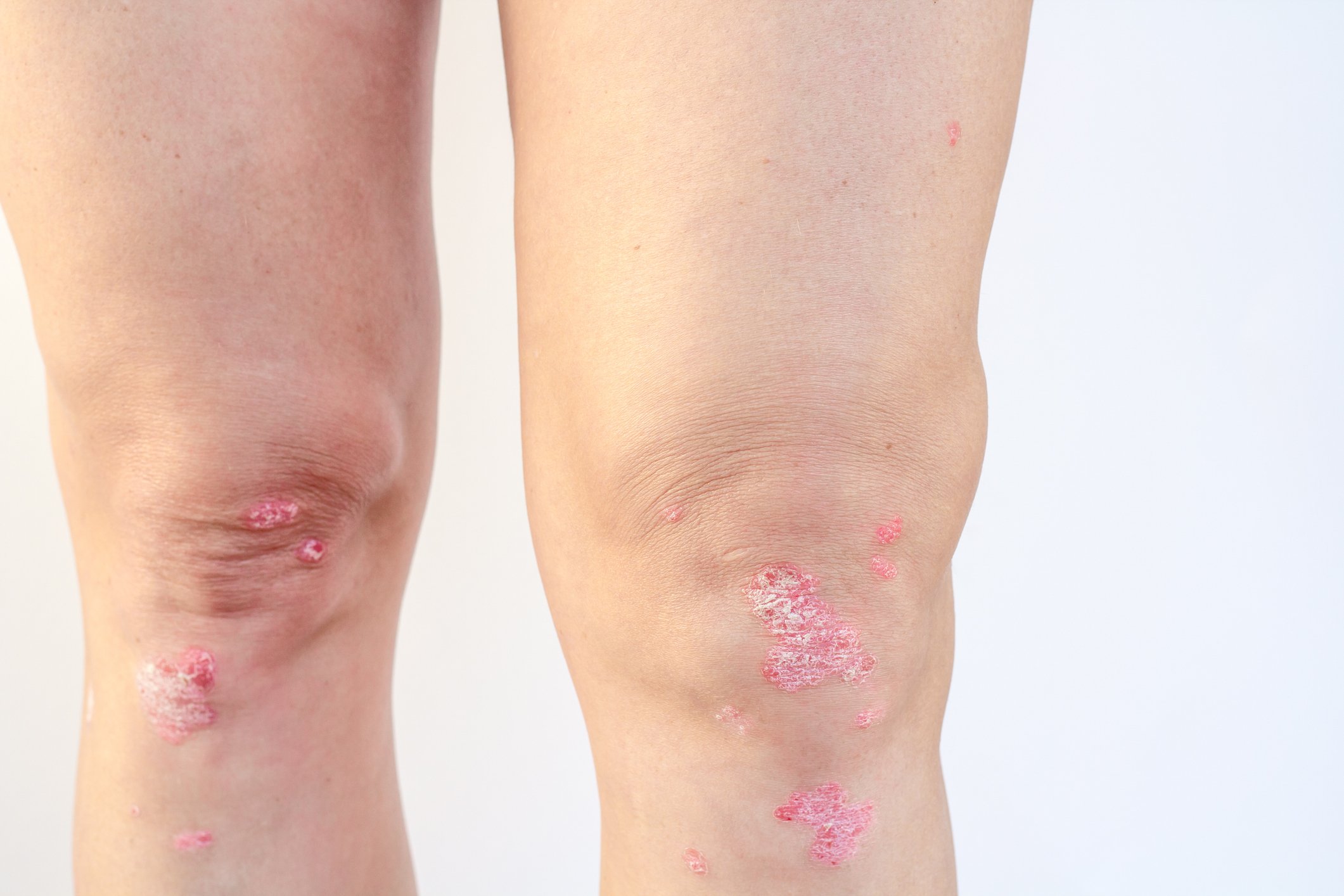

Patients with spondyloarthropathies (SpA) often suffer from extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (EMMs), which can also affect the gut [1, 2]. These multifaceted diseases with a complex clinical picture have both physiological and psychological effects [3, 4]. [3, 4]. Treatment must be individually tailored to the needs of those affected.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are among the most common EMMs associated with SpA [5]. In ankylosing spondylitis (AS), the prevalence of IBD is estimated at 5-10% and an increased risk of IBD has also been found in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [2, 6, 7]. In addition, 25-49% of AS patients were found to have subclinical inflammation and 50-60% microscopic inflammation, i.e. non-symptomatic intestinal inflammation [1]. These prevalences suggest a link between the gut and joints and raise questions about the potential involvement of the gut in SpA [8].

Similar inflammatory signaling pathways in joints and intestines

The link between joints and the gut is thought to be based on similar inflammatory signaling pathways [2]. Interleukin (IL-)17 plays a key role in the inflammatory responses underlying IBD and SpA and at the same time appears to have a potential protective function in the gut [8, 9]. In addition, signaling pathways via IL-23 and T helper cells-17 (TH17) are probably involved in the immune defense of the mucosa and epithelial tissue repair [9]. In vitro studies have shown that IL-17 and the IL-17-producing γδ T cells play a protective role in the intestine [9]. New cases and exacerbations of IBD have also been observed in clinical trials with IL-17 inhibitors [10, 11]. However, other molecules such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors can also be used for immunosuppression in inflammatory diseases. They act intracellularly and can thus modulate the response of a variety of proinflammatory cytokines involved in the development of intestinal inflammation [12]. Current data show that no IBD relapses were observed in AS patients treated with the JAK inhibitor RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) (15 mg/T) [13].

The treatment of SpA in EMMs

For patients with complex disease profiles, treatment should be tailored as closely as possible to their needs [14, 15]. It is therefore important to consider possible EMMs and pay attention to symptoms that may indicate IBD in addition to the rheumatic disease. In addition to the general condition and intestinal symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain or fecal incontinence, these include weight loss, anemia of unexplained cause and a higher than expected C-reactive protein (CRP) level [16, 17]. Preferred investigations for these symptoms include a colonoscopy including biopsies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a complete blood count [16, 17]. Other options include the measurement of fecal calprotectin, which can be influenced by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or an ultrasound examination [18, 19]. In individually tailored treatment, symptoms of active IBD are considered a contraindication to the use of IL-17 inhibitors [14]. In SpA patients, however, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms can always occur for reasons unrelated to IBD (abscesses, infections) [17]. If symptoms of IBD manifest, it is advisable to refer patients to gastroenterologists without delay. This also applies to clarification if the indications of IBD are not conclusive (Fig. 1) [20].

Figure 1: Practical considerations for the treatment of SpA patients with intestinal inflammation. EAM = extra-articular manifestations; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Adapted from [15-17].

New approval of RINVOQ® for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [21]

In addition to the approvals in rheumatology (rheumatoid arthritis [RA], PsA and AS) and atopic dermatitis (AD), the JAK inhibitor RINVOQ® is now also approved for the treatment of UC and CD in Switzerland* [21]. In contrast to rheumatic diseases, RINVOQ® is used in UC and CD as induction therapy (45 mg/T for 8 weeks [UC] or 12 weeks [CD]) and maintenance therapy (15 mg/T or 30 mg/T [UC & CD]) [21]. In the induction studies, patients in both indications showed a rapid response within a few days with a significant improvement in symptoms relating to bowel movement frequency and rectal bleeding [22, 23]. At week 52, 73 % (UC) resp. 60 % (CD) of bio-IR patients** treated with the higher dose of 30 mg/T RINVOQ® achieved clinical remission, compared to 8 % (UC) or 13 % (CD) with placebo [24, 25].

No new safety signals for RINVOQ® in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

In addition to rapid and sustained response, the placebo-controlled clinical UC and CD studies confirmed the favorable benefit-risk profile of RINVOQ® without any new safety signals, even at the higher doses (30 mg/T or 45 mg/T) [21, 24, 26]. Herpes zoster (15 and 30 mg), hepatic disorders (15 mg only) and neutropenia (30 mg only) occurred in a larger number of UC patients treated with RINVOQ® compared to placebo [27]. In contrast, side effects such as severe cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism and malignant diseases were comparable to the placebo group in UC patients even at the higher dosage of 45 mg/T RINVOQ® in the induction phase and 30 mg/T RINVOQ® in the maintenance phase [27]. The safety profile in patients with Crohn’s disease taking RINVOQ® is also consistent with the known safety profile of RINVOQ® [21].

Conclusion

JAK inhibitors are used for immunosuppression in inflammatory diseases. They act intracellularly and can thus modulate the response of a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in the development of intestinal inflammation [12]. The rapid and sustained remission as well as the favorable benefit-risk profile of RINVOQ® have also been confirmed in the two IBD indications UC and CD [21]. Practicing rheumatologists should monitor IBD as a possible EMM and consult a gastroenterologist if symptoms manifest [20].

* Indications/possible applications at www.swissmedicinfo.ch

** bio-IR: Patients who had an inadequate response to treatment with a biologic prior to RINVOQ® therapy, i.e. insufficient response, loss of response or intolerance to ≥1 biologic.

Brief technical information RINVOQ®

Literature

1 El Maghraoui, A., Extra-articular manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis: prevalence, characteristics and therapeutic implications. Eur J Intern Med, 2011. 22(6): p. 554-60.

2 Rudwaleit, M. and D. Baeten, Ankylosing spondylitis and bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2006. 20(3): p. 451-71.

3 Magrey, M., et al, The International Map of Axial Spondyloarthritis Survey: A US Patient Perspective on Diagnosis and Burden of Disease. ACR Open Rheumatol, 2023. 5(5): p. 264-276.

4 Bernabeu, P., et al, Psychological burden and quality of life in newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients.Front Psychol, 2024. 15: p. 1334308.

5. de Winter, J.J., et al, Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther, 2016. 18(1): p. 196.

6 Eppinga, H., et al, Prevalence and Phenotype of Concurrent Psoriasis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2017. 23(10): p. 1783-1789.

7 Li, W.Q., et al, Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn’s disease in US women. Ann Rheum Dis, 2013. 72(7): p. 1200-5.

8 Speca, S. and L. Dubuquoy, Chronic bowel inflammation and inflammatory joint disease: Pathophysiology. Joint Bone Spine, 2017. 84(4): p. 417-420.

9 Lee, J.S., et al, Interleukin-23-Independent IL-17 Production Regulates Intestinal Epithelial Permeability. Immunity, 2015. 43(4): p. 727-38.

10 Hueber, W., et al, Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut, 2012. 61(12): p. 1693-700.

11 Targan, S.R., et al, A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Study of Brodalumab in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol, 2016. 111(11): p. 1599-1607.

12 Salas, A., et al, JAK-STAT pathway targeting for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020. 17(6): p. 323-337.

13 Poddubnyy D. et al. Development of Extra-musculoskeletal Manifestations in Upadacitinib-treated Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, or Non-radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. OP0061 presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR), May 31-June 3, 2023, Milan, Italy.

14 Ramiro, S., et al, ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis, 2023. 82(1): p. 19-34.

15. NICE NG65‡. Spondyloarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng65. Last viewed: July 2024.

16 Magro, F., et al, Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis, 2017. 11(6): p. 649-670.

17 Gomollón, F., et al, 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis, 2017. 11(1): p. 3-25.

18 Waugh, N., et al, Faecal calprotectin testing for differentiating among inflammatory and non-inflammatory bowel diseases: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess, 2013. 17(55): p. xv-xix, 1-211.

19 Zakeri, N. and R.C. Pollok, Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol, 2016. 22(7): p. 2165-78.

20 IBD Standards. Standards for the Healthcare of People who have Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). 2013 Update. Available at: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/files.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/Publications/PPR/ibd-standards.pdfZuletztViewed: July 2024.

21. current technical information for RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) at www.swissmedicinfo.ch.

22 Loftus, E.V., Jr, et al, Upadacitinib Therapy Reduces Ulcerative Colitis Symptoms as Early as Day 1 of Induction Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023. 21(9): p. 2347-2358 e6.

23 Colombel, J.F., et al, Upadacitinib Reduces Crohn’s Disease Symptoms Within the First Week of Induction Therapy.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2024. S1542-3565(24)00254-4 Epub ahead of print.

24 Vermeire, S., et al, Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in patients responding to 8 week induction therapy (U-ACHIEVE Maintenance): overall results from the randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 maintenance study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023. 8(11): p. 976-989.

25 Schreiber SW. et al. P630. Upadacitinib Improves Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Moderate to Severely Active Crohn’s Disease Irrespective of Previous Failure to Respond to Biologics or Conventional Therapies. Poster Presented at ECCO March 2023. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2023(17)S1:i759–i760.

26 Loftus, E.V., Jr, et al, Upadacitinib Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med, 2023. 388(21): p. 1966-1980.

27 Blumenstein I. et al. P179 Comparative benefit-risk profile of induction and maintenance therapy with upadacitinib versus placebo in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. JCC, 2023. 17(Suppl.1): p. i333-i334.

The references can be requested by professionals at medinfo.ch@abbvie.com.

This article was produced with the financial support of AbbVie AG, Alte Steinhauserstrasse 14, 6330 Cham.

This article has been released in German.

Text: Dr. sc. nat. Katja Becker

CH-RNQ-240014 08/2024