Older divers are at increased risk for incidents. Fitness, technique and calculated risk reduce potential hazards and problems during diving. Diving and sports medicine consultation is important.

For decades, recreational diving has enjoyed great popularity. The technical developments of the equipment, but also the great spread of diving lead to new challenges – also for the general practitioner as examiner and advisor in questions around diving trips. Scuba diving is a relatively safe sport, even though fatal incidents are reported in the daily press from time to time. To what extent can primary care physicians help ensure that safety remains this high?

SUHMS is the professional society of Swiss underwater and hyperbaric physicians. Continuing education is offered on a regular basis for the examination of divers. The question of the suitability of the older diver for diving is not only of concern due to the frequency of the question, but also because there is hardly any scientific literature on the subject to date. The question is too young. The Manual on Fitness for Diving [1] was published by Swiss experts and provides a basis for assessing divers with regard to their medical problems.

Research Situation

Significant research data in the field of diving often comes from military and/or professional diving (offshore). These data have provided many diving physiology and pathophysiology insights, but are not necessarily applicable to recreational diving because the requirements for recreational divers are different. Newer databases such as that of DAN, with hundreds of thousands of registered dives, provide practical data, but have not yet been evaluated in all respects.

Basic research shows us changes that occur with age. Epidemiology adds to this the pathologies typical of old age.

Last but not least, we find in exercise physiology and sports medicine safety-relevant preventive possibilities, so that the older diver resp. competently advise the aging diver. Intraindividual differences are enormous, so it is worthwhile to identify risk factors as well as protective factors and resources for safe diving. Own diving experience offers an advantage not to be underestimated.

Diving medical relevant changes in old age

Body composition changes throughout life. Muscle mass decreases from about the age of 45. This often leads to sarcopenia in older age. Muscle strength decreases 1-2% per year with significant acceleration after retirement age. In particular, the fast muscle fibers (type 2) dwindle, which is of great importance for the reserve capacity of the neuromuscular system. Fast reactions, sprinting performance and high power efforts are only possible to a reduced extent. In turn, fat mass increases in most individuals.

The changes in the musculature lead to reduced resilience under difficult diving conditions. The increase in fat mass leads to an increase in so-called slow tissue, which can lead to an increased risk of decompression sickness for saturation/desaturation, especially during repetitive dives (such as those performed during diving vacations).

During diving, ambient pressure results in a fluid shift toward the heart because venous pooling no longer functions as it does under standard gravity conditions. This leads via an increased preload to greater cardiac stress and ultimately to the well-known diver’s diuresis. A barely compensated heart can decompensate or fail under this increased load. coronary artery disease lead to acute coronary syndrome.

From the scientific, epidemiological and diving medical literature, the following facts are essential for our assessment of fitness for diving and for counseling: Evidence of cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and metabolic disease, especially diabetes mellitus, should be systematically sought. If the history reveals symptoms such as dyspnea or a drop in performance, further clarification is indicated.

Evidence on risk at older ages

In the classical diving medical literature, the diver over 40 years of age is referred to as an older diver. The literature here is based primarily on studies with professional divers, which is not useful for our purposes.

It appears based on a smaller study (Hawaii with approximately 100 incidents) that older divers are at increased risk for decompression illness of more severe severity and with less recovery. However, the data situation is not solid due to the small numbers.

The number of dives by older divers is steadily increasing, so we will probably have better data regarding the risk of older divers in the future. Evaluation of large cohorts (e.g., recorded dives and incidents DAN), diving incidents (Australia 2001-2014, UK BSAC annual reports), and incidents reported through DANSuisse or recorded through the FTU does not allow reliable conclusions about the risk of incidents at older ages.

How fit is “diving fit”?

Ultimately, no one can answer this question precisely. However, there are indications of what physical performance in METS (1 MET = resting conditions) is required under certain diving conditions. This serves as a reference. Under calm diving conditions, the output is approximately 7 METS. The goal is to be significantly higher with the possible performance or to minimize the dive-related risks accordingly. If one builds in a reserve for sudden aggravated conditions, one can probably assume a performance of 10 METS. If this performance is achieved without any problems on the ergometer or treadmill, one may assume safe diving under usual conditions with little additional risk.

Microgas bubble formation appears to be increased in overweight individuals and those in poor physical condition, which in turn increases the risk of a decompression incident.

Calculated risk

Particularly relevant for the consultation are the available physical and technical reserves compared to the risk taken. Well trained, technically proficient and experienced older divers have correspondingly much greater reserves if they find themselves in a situation with increased demands. This is e.g. the case with longer swimming distances (boat place not found, boat gone), with unexpectedly occurring currents or with drift diving as well as with health and technical problems with the diving partner or with oneself with the necessity to fix the problem under water, to make a controlled emergency ascent or even a partner rescue with subsequent surface transport.

In these and similar situations, the physical and mental demands are significantly increased and limited reserves are quickly depleted. This can trigger an acute somatic problem (for example, essoufflement or acute coronary syndrome) in predisposed divers or a panic reaction with ultimately uncontrolled ascent and risk of pulmonary barotrauma or decompression sickness. Effort underwater leads to increased nitrogen saturation, which in turn increases the risk of decompression sickness.

These dangers are countered primarily through prevention and, for our target group, through the exclusion of a predisposing disease and training. If you take preventive measures, you stay fit for diving longer and dive considerably safer.

Knowledge around diving and good underwater diving skills are desirable. Low-stress diving and good breathing further reduce exertion. This also reduces the amount of lead required and comparatively reduces the physical strain. A training-induced increase in physical reserve therefore postpones the limit to exhaustion and thus reduces the risk of a panic reaction with uncontrolled ascent. Safe diving means having reserves. Training means building up reserves.

Based on theoretical considerations, the risk of suffering more severe consequences or even death is significantly increased if a serious medical problem occurs underwater. This risk should be minimized by the diving medical examination and consultation.

The risks taken with the place of diving (natural hazards, safaris without fast medical care), the type of diving (compressed air, nitrox, technical diving with other mixed gases) and the exhaustion of the duration (decompression dives) as well as the number of dives per time are the responsibility of the diver. If these aspects are taken into consideration, the safety of diving can still be significantly increased.

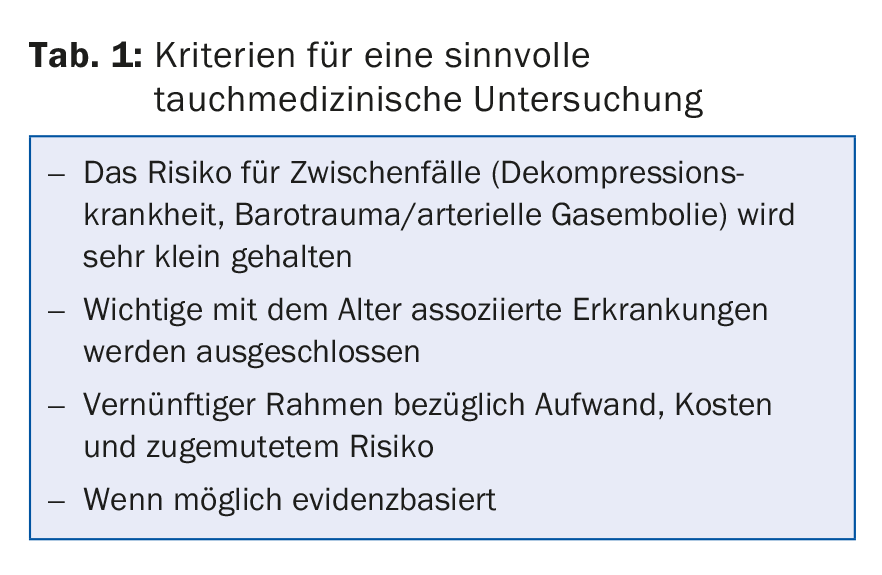

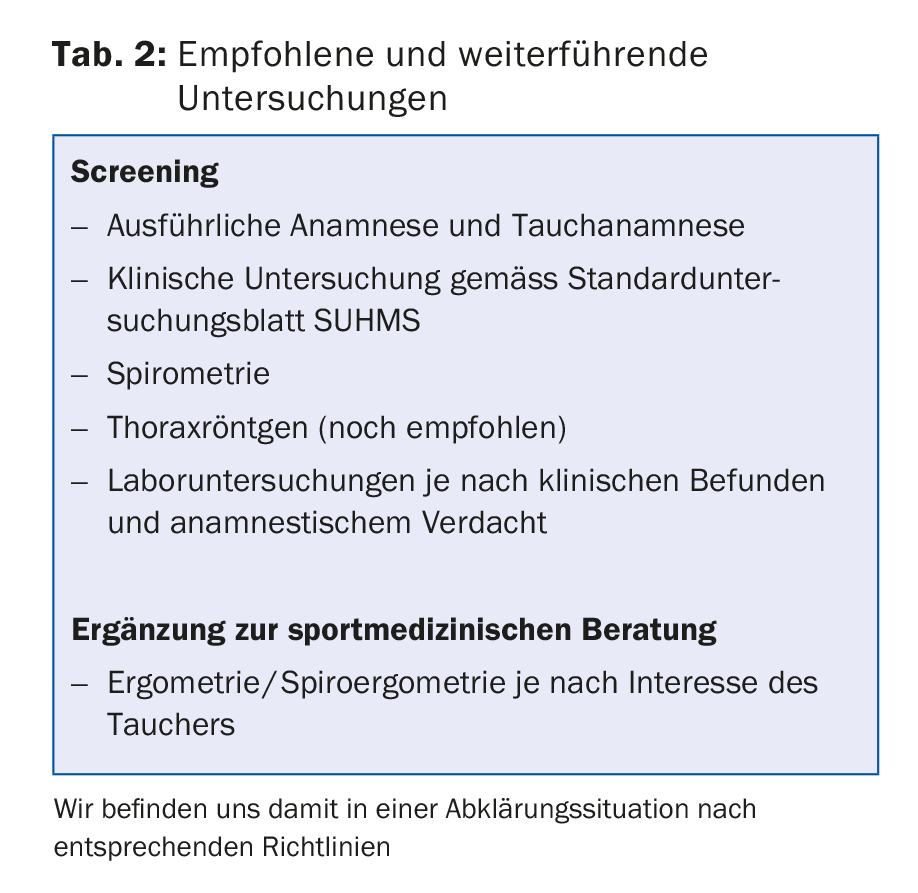

Our diving medical examination/consultation (Tab. 1 and 2) and the health behavior of older divers allow overall safe diving even into older age.

Take-Home Messages

- Older divers are at increased risk of diving incidents.

- Fitness, technique, and adjusted calculated risk allow for a significant reduction in potential hazards and problems during diving.

- Diving and sports medicine advice are basics for safe diving in old age.

Literature:

- Wendling J, et al: Manual Tauchtauglichkeit SUHMS. With the collaboration of GTÜM. 2nd edition, 2001.

Further reading:

- Carturan D, et al: Ascent rate, age, maximal oxygen uptake, adiposity, and circulating venous bubbles after diving. Journal of Applied Physiology 2002; 93(4): 1349-1356.

Further literature from the author

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 16-18