The pleura is involved in approximately 30% of all diseases affecting the respiratory system. This is often characterized by the appearance of an effusion. The total incidence of pleural effusions in Western industrialized countries is approximately 300/100,000.

The pleura is involved in approximately 30% of all diseases affecting the respiratory system. This is often characterized by the appearance of an effusion. The overall incidence of pleural effusions is high, approximately 300/100,000 in Western industrialized countries. Concomitant cardiac, hepatic and renal diseases are usually transudates with a proportion of 40-46%. Exudates requiring clarification are estimated to be as high as 60% in a mixed internal medicine patient population. These are divided 40-45% by inflammatory-microbial causes, 20-30% by malignant effusions, and 10-18% by reactive effusions, e.g., thromboembolism. The remainder includes rare causes and idiopathic effusions.

Basic

The pleural space measures approximately 5-30 µm. Normally, up to 15 ml of pleural fluid is found in the pleural cavity, a microvascular filtrate of the parietal pleura. Pleural pressure results from the expanding force of the thoracic wall, the elastic retraction force of the lung, and hydrostatic capillary pressure and oncotic pressure. The result is a slight influx of fluid into the pleural space. Fluid is exchanged via the lymphatic vessels of the parietal pleura, usually about 15-30 ml per 24 h and per hemithorax. This can be increased to 500 ml. Changes in pressure ratios, drainage ratios, or increased production in the setting of inflammatory or malignant processes ultimately lead to the development of pleural effusion, the former usually resulting in a transudate, the latter in an exudate.

Thoracic ultrasonography, as a technique available almost everywhere, or computed tomography can better visualize pleural changes, far better than the chest radiograph. They allow a descriptive classification. The character and extent of pleural changes, presence of effusion, its size, chambering, relations of changes to the lung and thoracic wall are recorded. In addition, a targeted biopsy can be performed using imaging techniques. However, they may also reveal etiologic clues such as central thrombi as a clue to pulmonary emboli.

W. Frank suggested four key questions to set up the diagnosis: (1) does thoracentesis need to be performed? (2) Is it a transudate or an exudate? (3) What is the underlying etiology of the effusion in the case of exudate? (4) When are which bioptic techniques indicated? Already the effusion diagnosis leads with a high probability to a clarification (up to 75% of the cases). The addition of endoscopic-bioptic procedures leads to an increase to over 90%. This is the basis for the algorithm presented.

Pleural puncture – thoracentesis

Thoracentesis is indicated when effusion is present and clinical considerations do not clearly support a transudate. Today, the puncture is usually performed with sonographic support. The needles should not be undersized in order to be able to remove viscous material if necessary. Local anesthesia can be useful, but does not always have to be performed, since the mere trial puncture hardly exceeds the extent of the anesthetic puncture. Multiple punctures may be necessary for chambering, but may also yield different findings. Bilateral effusions usually do not require invasive workup on both sides because they correlate predominantly with respect to key parameters. A collection of 20-30 ml of effusion is sufficient for diagnostics. Withdrawal of larger volumes is usually done for therapeutic indication to reduce respiratory distress and is often an emergency measure.

First assessment steps

First, the effusion is visually assessed. Clear or cloudy effusion and pus (empyema) are distinguished, as well as bloody or chyle effusion. The smell is also an important criterion. Foul odor often characterizes empyema. Sedimentation and centrifugation may reveal turbidity due to cell debris. Hemoglobin or hematocrit determination allows differentiation between hemorrhagic effusion and hematothorax. Differential diagnosis between chylous and pseudochylous effusions is possible by determining the triglycerides in the effusion.

Chemical analysis

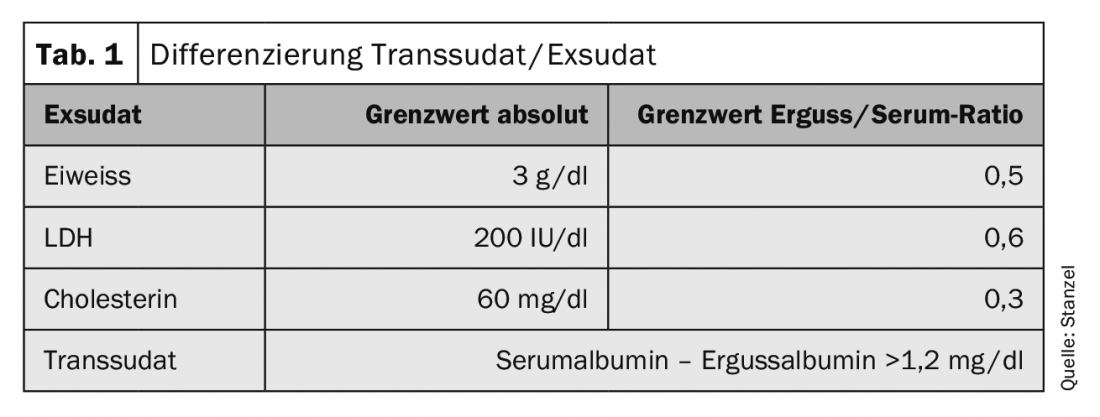

The next step is the analysis of the protein content. Classification into transudate or exudate is performed according to the Light criteria. If there is a clear explanatory disease for a transudate, the general doctrine is that there is no need to proceed further diagnostically. Also, malignant effusion is largely excluded if a transudate is present. Passive transudates have been described in lymphangiosis carcinomatosa of the pleura or in malignant lymphoma of the pleura, so that occasionally the diagnosis must also be extended in the case of transudate. Repeated punctures and therapies such as diuretic medication may also cause a change. The additional LDH determination may be helpful to detect transudates whose protein levels are elevated only because of diuretic therapy. In the case of exudate, however, further clarification is usually required.

A decisive step is the protein determination in the pleural fluid (Tab. 1) . The significance is improved by evaluating the pleural value in relation to the serum value. Additional analysis of the LDH level in the pleural effusion in relation to the serum value improves sensitivity. The determination of cholesterol can contribute to further differentiation. In chylous effusion, the determination of triglycerides or chylomicrons leads to the diagnosis in addition to the visual characteristic findings. Differentiation of “pseudoexudates” can be difficult. These are chronic transudates or transudates modified by diuretic therapy. Amylase determination in effusion may reveal an association with acute and chronic pancreatitis or esophageal perforation. Other parameters can also be included in the diagnostics. Depending on the underlying disease, the determination of neutrophils, pH, NT-proBNP or rheumatoid factor or other parameters may be helpful.

Determination of pH is important in both parapneumonic and malignant effusion. A pH ≤7.30 is usually found only in empyema, rarely in tuberculous effusion or advanced malignant pleural effusion. In conjunction with decreased glucose, this suggests pleural thickening and inhibition of transfer between blood circulation and pleural space. For pH determination, the fluid obtained is analyzed in the same way as a blood gas analysis. pH and glucose depression are measures of the severity and extent of a pleural process.

The diagnosis of tuberculous effusion is particularly challenging. Marked lymphocytosis in the effusion, high protein and LDH levels with concomitant decreased glucose may be indicative of a tuberculous etiology. Microscopic and cultural detection of tuberculosis is not easy and is successful in only about 25% of cases on average. Determination of adenosine deaminase (ADA), a macrophage- and T-cell-associated inflammatory enzyme, can increase sensitivity at a cut-off of 47 U/ml in the enzyme assay. DNA amplification techniques to detect DNA sequences specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis are useful. These may allow rapid detection of tuberculous pleurisy. However, sensitivities and specificities vary more widely. The diagnosis should therefore never be based on a single finding alone.

Cytology

Cytologic examination of the effusion is a very simple and widely used procedure and should be included in the initial examination of the pleural effusion except for the transudate. Malignancy may already be proven by a positive cytologic finding, whether due to malignant infiltration of the pleura or pleural involvement by metastasis. However, the results of studies vary widely depending on tumor disease and extent. Patients with a malignant effusion and an effusion pH below 7.30 had positive cytologic findings in 78%. At an effluent pH above 7.30, this value dropped to only 51%. Molecular and cell biology methods enable new approaches. Both inflammatory and oncologic markers are now well established. Immunocytology in particular allows earlier and more sensitive diagnosis. In addition, when a panel of diverse markers is used, the differential diagnosis between mesothelioma and adenocarcinoma becomes easier.

Needle biopsy

Adding a biopsy of the pleura when an initial cytologic examination did not clarify the situation is controversial and rarely used today. Only for the clarification of tuberculous pleurisy just the pleural biopsy contributes significantly. Caseating granulomas were detectable in needle biopsies in 79.8% of patients in a study of 254 patients, and the others were confirmed by cultural examination. The clearing rate depends on the number of biopsies and reaches an optimum when six or more biopsies are taken or when pleural tissue is detected in at least two of the biopsies. With a high incidence of tuberculosis, the combination of ADA determination, lymphocyte predominance, and needle biopsy yields the highest rate of diagnosis in unexplained exudate.

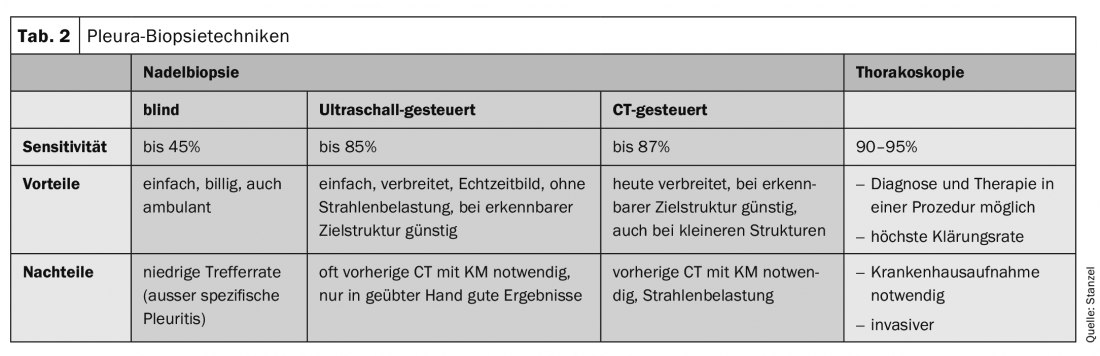

In malignant effusion, blind needle biopsy is far less sensitive than effusion cytology. Compared with thoracoscopy, needle biopsy is also significantly inferior (36% vs. 87%). In conjunction with modern imaging techniques such as thoracic sonography or CT, definitive diagnoses are more frequently made. The quality of biopsies obtained with the automatic cutting needle is excellent because they are usually obtained without artifact and correspond to smoothly cut punch cylinders. Needle biopsy under sonographic control or CT-guided yields good results, especially when pleural thickening or nodularity is detectable and can be targeted with the needle under imaging control (Table 2).

Thoracoscopy

After exhausting the possibilities mentioned so far, a not inconsiderable proportion of about 20-25% of effusions remains unexplained. The algorithm is then followed by thoracoscopy as the next step. Wait and see” is usually only an option in critically ill patients in very poor general condition. If definitive clarification is reasonable, desired, and there are no contraindications and the results of thoracoscopy are likely to modify the procedure, it should be performed. Another argument for thoracoscopy is often the additional option of thoracoscopic pleurodesis, especially in cases of large and/or recurrent effusions. In this way, diagnosis and interventional therapy even take place in one step.

Jacobaeus first performed thoracoscopy in 1910 to diagnose exudative pleurisy. Already since the 1970s with Brandt and Loddenkemper in Germany and Boutin in France, this method was established in Europe for the clarification of pleural diseases and pleural effusions. In combination with modern video technology, this gave rise to the video thoracoscopy in HD quality that is common today (Fig. 1).

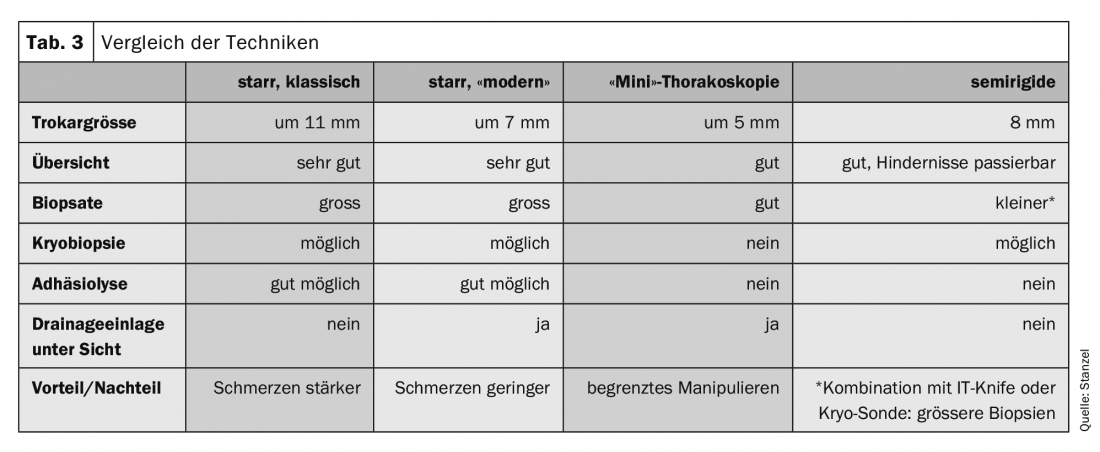

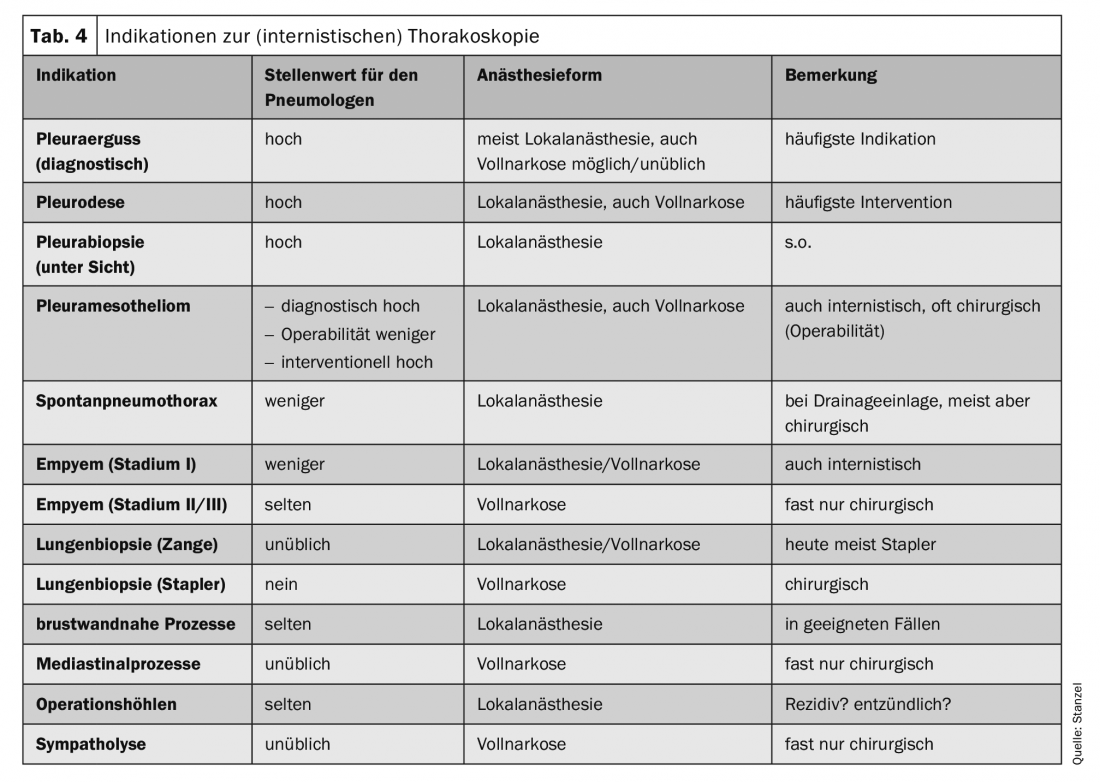

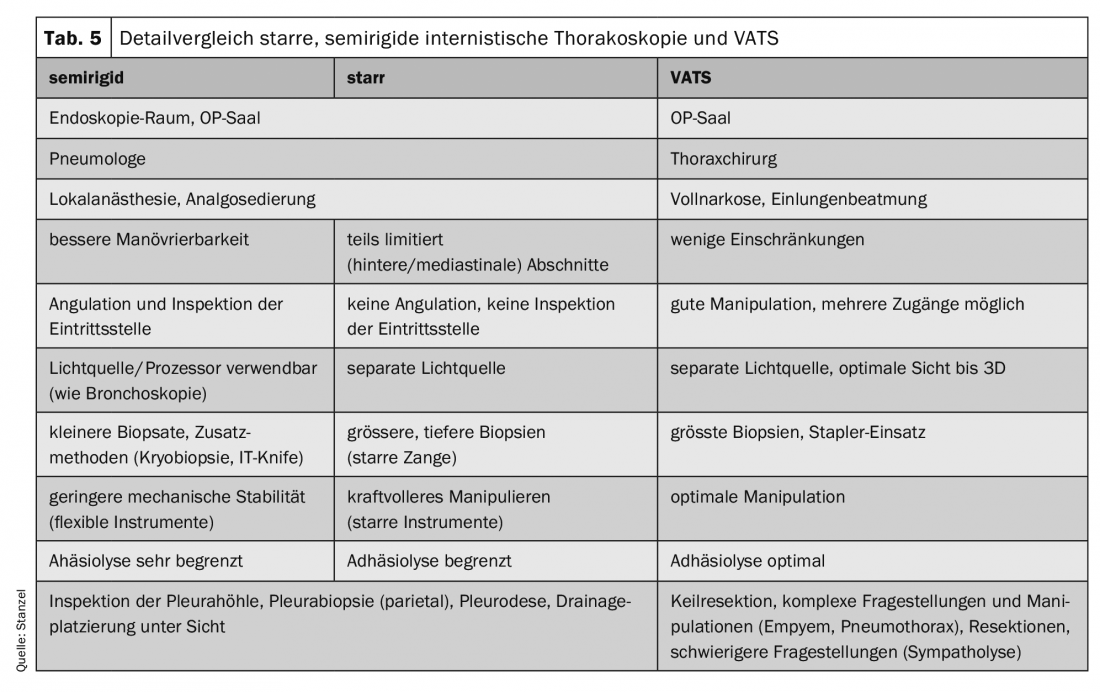

Classically, internal thoracoscopy – “medical thoracoscopy” in English – is performed under local anesthesia in sedation in endoscopy rooms with reusable instruments and has a predominantly diagnostic character (tab. 3) . However, there are also therapeutic options in the hands of the interventional pneumologist. Thoracoscopy, especially interventional thoracoscopy, can then be performed under general anesthesia. The indications for thoracoscopy are listed in Table 4. The respective indication is very closely linked to the anesthetic form and technique. In Germany, only the clarification and therapy of pleural effusion and pleural biopsy under visual inspection are still widespread and more widely accepted as internal medicine indications.

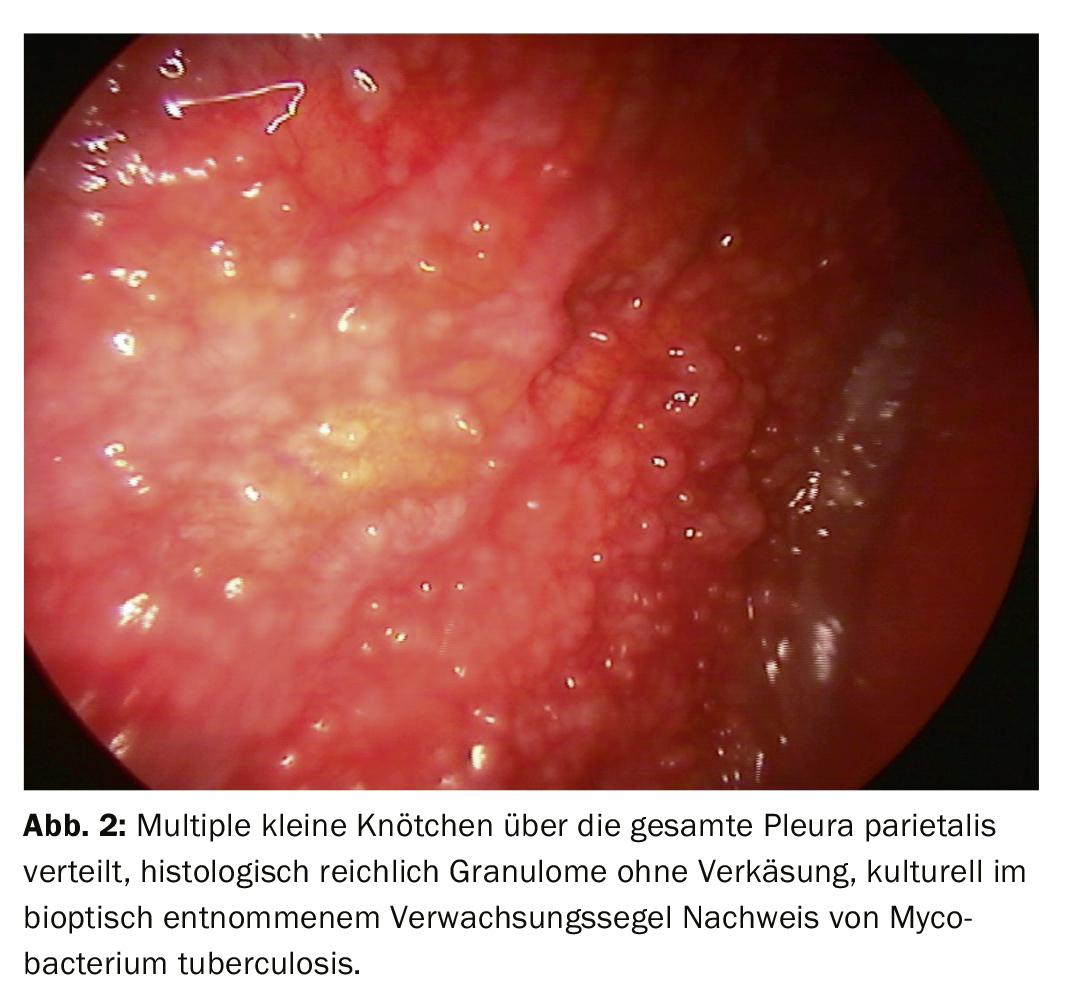

After a stepwise process of diagnosis, the focus is usually on differentiating an inflammatory event from a malignant effusion (Fig. 2). Histology from forceps biopsies of the pleura allows clearer classification. In modern oncology, however, the further processing of tumor tissue also plays a major role because molecular analyses can have a decisive influence on therapy, particularly in the case of lung carcinoma. Thus, it may be important to provide not only cytologic material but also larger biopsies for examination, which can be easily obtained via direct forceps biopsy or cryobiopsy during thoracoscopy, even if only discrete tumor manifestations are apparent (Fig.3). Pleural mesothelioma as an important differential diagnosis in malignant effusion has decreased significantly in frequency. However, especially in this case, the better differentiation and histological classification based on the biopsy material obtained during thoracoscopy can be a good indication (Fig. 4).

Some pulmonologists also consider the early phase of parapneumonic effusion or empyema an indication for internal thoracoscopy, but then more from a therapeutic point of view. As the clinical picture progresses to complicated empyema, VATS by the thoracic surgeon comes into consideration more and more because debridement becomes more important. When differentiation of pleurisy from specific pleurisy cannot be made with sufficient certainty by less invasive diagnostic methods, thoracoscopy results in a clarification rate >90%. In addition to histological and additional microbiological processing of tissue samples, materials obtained during debridement (fibrin deposits, sails and chambers) must also be given for further examination (Fig. 2) . In the case of these issues, the material must also be processed further in a suitable manner (saline solution, rapid processing). Highly sensitive techniques such as PCR are less frequently required.

In pneumothorax, thoracoscopy is now usually performed as VATS by the thoracic surgeon when there is an indication for surgery. In some centers, it is or has been argued that when a chest drain is inserted in a symptomatic pneumothorax, an internal thoracoscopy can very well also determine the further strategy and this can be done via the same access before drain insertion. However, since recommendations for pneumothorax are currently moving toward single puncture with small-lumen catheters as initial therapy, internal thoracoscopy is rarely performed with this indication.

The equipment used to perform thoracoscopy consists of rigid instruments such as trocar with sleeve, valve, optics, forceps, and suction (Tab. 3, 5). For examination under local anesthesia, instruments with smaller diameters are common today, usually around 6-7 mm. Larger instruments with 10-12 mm diameter are also used, mainly under general anesthesia. mm diameter are used, but are hardly common anymore. A larger instrument diameter also causes more pain and discomfort during and after thoracoscopy. The “minithoracoscopy” is performed with even smaller instruments around 3 mm in diameter, the sleeve then has an outer diameter around 5-6 mm. Then the procedure is less invasive and associated with less pain. The results are comparable to the standard procedure.

Alternatively, a semirigid instrument was developed that resembles a flexible bronchoscope and can also be moved around obstacles due to the angulation capability. Main disadvantages are smaller biopsies and often more difficult biopsy removal than with rigid forceps. However, these disadvantages can be partially compensated by using additional techniques (electric knife with electrocautery or cryobiopsy technique).

The pneumothorax required for the examination is created either passively by admitting room air, usually after or with removal of an effusion, or actively via an insufflator. Localization of the effusion and pneumothorax creation are most easily performed under sonographic control. Pneumothorax creation can be safely performed even in the presence of the smallest effusions or absence of effusion. The fluoroscopy control is hardly common today. In most cases, the examination is performed via only one access. Occasionally, it may be necessary to create a second access site, especially if adhesions are present, to view additional areas and take biopsies.

Thoracoscopic results are best in pleural carcinomatosis (Figs. 3, 4). Needle biopsy clears 44%, cytology 62%, thoracoscopy alone as much as 95%, and in combination with the other procedures as much as 97%. In malignant mesothelioma, thoracoscopy makes a significant contribution to histologic confirmation, although it is more difficult. An exact staging and determination of the further procedure are carried out. It can also be clarified whether resection is promising. For tuberculous pleurisy, the figures for clarification are: needle biopsy 51%, + culture 61%, thoracoscopy (+ culture) 99% (Fig. 2).

One advantage of thoracoscopy is more accurate diagnosis. In a French study, 168 internal thoracoscopies were analyzed. In 66 patients, the diagnosis was nonspecific pleurisy after the entire diagnostic workup. In only 34 was the diagnosis confirmed by thoracoscopy. On the other hand, 16 were found to have malignant mesothelioma, 10 had pleural carcinomatosis with adenocarcinoma, 3 had undifferentiated carcinoma, and 3 had specific pleurisy. Relatively often, the diagnosis finally made thoracoscopically changes the entire subsequent procedure. The procedure was modified in 155 of 182 patients.

Biopsy of the pleura is performed under direct vision, and the number of biopsies taken should be between 2 and 6. In any case, sufficient material should also be available macroscopically, especially if additional comprehensive diagnostics are performed as is common today (immunohistology, molecular analysis). If a clear target structure is lacking, multiple areas should be biopsied. The biopsy should be performed parietally on the rib. Visceral biopsies are associated with the risk of prolonged air leak, and those in the intercostal space with bleeding from the intercostal vessel or injury to the nerve. By lifting and pulling sideways, the pleura can often be peeled off in a tapestry-like fashion, allowing a larger biopsy to be obtained safely. In this process, patients may move and become restless even under analgesia when in pain. An additional local injection is unusual and usually not necessary. As a rule, the biopsy material is placed in formalin and histologically processed. If the cause is infectious, especially if a specific cause is suspected, material must also be placed in saline and rapidly transferred to an appropriate laboratory. Electrosurgical biopsy or cryobiopsy are new ways to increase yield, especially when working with the semirigid instrument.

Patients who have malignant pleural effusion and are symptomatic often have extensive effusion. Chemotherapy is not always a promising treatment, especially when effusion-related respiratory distress is the primary concern and needs to be remedied quickly. Here, thoracoscopy simultaneously offers a therapeutic option with the performance of pleurodesis, usually by additional talc insufflation. Success rates are usually reported as >90%.

An absolute contraindication to thoracoscopy is adhesion and agglutination of the pleural space, as can occur in advanced malignant processes, especially pleural mesothelioma. Inflammatory processes and empyema can also cause this, as can previous surgery or pleurodesis. Relative contraindications include marked dyspnea or hypoxemia that is not effusion-related. Others include an unstable cardiovascular situation, a bleeding condition, an insatiable cough, and marked pulmonary hypertension or obesity.

Internal thoacoscopy is a safe procedure and is characterized by a low complication rate when performed by a trained and experienced examiner. The BTS Pleural Disease Guideline reports a mortality of 0.34%, which is often at the expense of talc poudrage. Other complications such as empyema, hemorrhage, ductal metastasis, air leakage, pneumothorax, or pneumonia occur in up to 1.8%, and minor complications such as subcutaneous emphysema, minor hemorrhage, local infection, hypotension, or fever occur in up to 7.3%. There are slightly lower complication rates for semirigid thoracoscopy compared with rigid thoracoscopy. Bleeding from an intercostal vessel is a serious complication that can usually be avoided. Then thoracic surgery may be necessary. Therefore, it is sometimes recommended that thoracoscopy be performed only when a thoracic surgeon is available in an emergency.

Summary

Internal thoracoscopy is a safe diagnostic procedure with few complications and a high diagnostic rate. Key characteristics are less invasiveness compared to VATS, less effort, and lower cost. Thus, thoracoscopy is at the end of a workflow (algorithm) that leads to clarification of the cause of pleural disease in more than 90% and also provides therapeutic options, most commonly used in malignant effusion, but also in parapneumonic effusion or empyema and pneumothorax.

Take-Home Messages

- In the case of unclear pleural effusion, the clarification rate by internal thoracoscopy increases to more than 90%.

- Internal thoracoscopy is a minimally invasive procedure performed under local anesthesia with analgesia.

- Sonography of the thorax has replaced fluoroscopy as an adjunctive technique in the planning and performance of thoracoscopy.

- If circumscribed pleural lesions are present, sonographic- or CT-guided needle biopsy may clarify the situation; in the case of diffuse changes, thoracoscopy is usually the only option.

- The recurrent malignant effusion can be diagnostically clarified thoracoscopically in one session and definitely eliminated by talc poudrage.

Literature:

- Light R: Pleural Diseases. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2007.

- Collins TR, Sahn SA: Thoracocentesis. Clinical value, complications, technical problems, and patient experience. Chest 1987; 91(6): 817-822.

- Seijo LM, Sterman DH: Interventional pulmonology. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(10): 740-749.

- Hooper CE, Lee YCG, Maskell NA: Setting up a specialist pleural disease service. Respirology 2010; 15(7): 1028-1036.

- Stanzel F, Ernst A: Diagnostics of pleural diseases. Pulmonologist 2008; 5: 211-218.

- Frank W. Diagnostic procedure in pleural effusion. Pulmonology 2004; 58: 777-790.

- Ferrer J: Tuberculous pleural effusion and tuberculous empyema. Sem Crit Care Med 2001; 6/22: 637-646.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Janssen JP, Astoul P: Thoracoscopy: general overview and place in the diagnosis and management of pleural effusion. Eur Resp J 2006; 28: 409-421.

- Rahman NM, on behalf of the British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Local anaesthetic thoracoscopy: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2): ii54-ii60.

- Loddenkemper R: Thoracoscopy – state of the art. Eur Resp J 1998; 11: 213-221.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Janssen JP, Astoul P: Thoracoscopy: general overview and place in the diagnosis and management of pleural effusion. Eur Resp J 2006; 28: 409-421.

- Tassi G, Marchetti G: Minithoracoscopy: A Less Invasive Approach to Thoracoscopy. Chest 2003; 124: 1975-1977.

- Pyng L, Mathur PN, Colt HG: Advances in Thoracoscopy: 100 Years since Jacobaeus. Respiration 2010; 79: 177-186.

- Alraiyes AH, Dhillon SS, Harris K, et al: Medical Thoracoscopy: Technique and Application. PLEURA 2016; 3: 1-11.

- Janssen JP: Why you do or do not need thoracoscopy. Eur Respir Rev 2010; 19: 117, 213-216.

- Woolhouse I, on behalf of the BTS Mesothelioma Guideline Development Group: British Thoracic Society Guideline for the Investigation and Management of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Thorax 2018; 73: i1-i30.

- Blanc FX, Atassi K, Bignon J, Housset B: Diagnostic Value of Medical Thoracoscopy in Pleural Disease – A 6-Year Retrospective Study. Chest 2002; 121: 1677-1683.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(1): 8-14.