A variety of medications can cause drug side effects on the small and large intestines. The focus will be on the major gastrointestinal drug side effects and their main triggers. The five major gastrointestinal symptoms discussed here are diarrhea, constipation, nausea, gastrointestinal bleeding, and abdominal pain. The triggering drug groups discussed are mainly antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), chemotherapeutic agents, psychotropic drugs and opiates.

A variety of medications can cause drug side effects on the small and large intestines. In the following, we will focus on the most important gastrointestinal drug side effects and their main triggers. The five major gastrointestinal symptoms discussed in this manuscript are diarrhea, constipation, nausea, gastrointestinal bleeding, and abdominal pain. The triggering drug groups discussed are mainly antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), chemotherapeutic agents, psychotropic drugs and opiates. In addition, individual special aspects of gastrointestinal drug side effects are discussed.

Gastrointestinal drug side effects are symptoms of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that significantly improve or subsequently disappear when drug therapy is omitted. Evidence of GI side effects is considered to be recurrence on re-exposure. However, because therapeutic alternatives often exist and the impairment from side effects can be significant, re-exposure should be resorted to only when no reasonable therapeutic alternatives exist.

Essential to identifying drug side effects on the GI tract is a careful (drug) history. Without this, attempts to identify a cause for GI symptoms often lead to repeated endoscopies with and without mucosal biopsies, which ultimately pose a (small) risk to patients, incur significant health care costs, and are generally frustrating for both physician and patient because they do not explain symptoms. The history is often complicated by polypharmacy and also by potential drug interactions. Before therapy of gastrointestinal symptoms that are not further explained by further drug prescriptions, drug side effects should be considered in any case.

In recent years, new insights have emerged that should be taken into account in clinical practice. This often allows drug side effects to be detected and clearly identified at an early stage. However, new possibilities for the therapy of such drug side effects have also been described. Because multimorbid patients are often seen on a number of medications in the clinical setting, knowledge of gastrointestinal side effects and potential drug interactions is increasingly important.

Drug-induced diarrhea (DID).

Diarrhea is one of the most common drug side effects of all. It accounts for more than 7% -of- all drug adverse events [1]. There are over 700 active ingredients known to cause diarrhea [1]. Basically, it can be stated that almost all drugs can trigger diarrhea in individual cases. Even opiates, for which constipation is the main gastrointestinal side effect, can be the cause of diarrhea in individual cases. This will be discussed later.

The mechanisms that trigger diarrhea are different for each drug class. Thus, both secretory or osmotic diarrhea or a mixed form occur as drug side effects. In addition, drugs can affect motility or, in individual cases, trigger inflammation of the intestinal mucosa. Only in the latter case will a histologic correlate to the symptomatology be found; in the vast majority of cases this is not the case (Table 1).

The symptom of drug-induced diarrhea is particularly common as a side effect of antibiotic administration (e.g., 2-3% with azithromycin but up to 19% with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) [2]. In addition, diarrhea is particularly common with proton pump inhibitors (PPI), antihypertensives, and metformin. In addition, it should be taken into account that magnesium can be a cause of diarrhea. Thus, diarrhea occurs in -11-37% of all patients treated for muscle spasms [3]. In addition, it should be taken into account that the use of laxatives also naturally leads to diarrhea. Laxatives are not always perceived as such or chronic -diarrhea attributed to laxative use by the patient. A careful anamnesis should therefore also include the question of the use of laxatives when diarrhea occurs. Their frequent prescription and easy availability as “over the counter” medications lead them to be a major cause of diarrhea as a -drug side effect [4,5]. It is not uncommon for laxatives to be used intentionally for weight loss.

As mentioned, the most common side effect of opiates is constipation. This will be discussed in more detail later on. Very rarely, however, opiates can also cause diarrhea. It should be borne in mind that opiate tablets can sometimes contain lactose as a filler, which can of course trigger diarrhea in patients with lactose intolerance. For example, there are morphine tablets that contain 90 mg of lactose, especially in low doses of 10 mg [6]. Oxycontin, which is widely used in the United States and Canada, contains 69 mg of lactose in the 10 mg dosage. Even in the 80 mg dose, it still carries 78 mg of lactose [6]. So, in case of doubt, it is also important to look at the composition of the drug preparations. Lactose is still frequently used as an additive. So occasionally it is not the actual ingredient in the medication, but one of the additives that causes diarrhea.

The ingredient of drug preparations does not always cause diarrhea via direct mechanisms, as shown in Table 1 . Recently, it has been described that 24% of all drugs can alter the intestinal microbiome, indirectly leading to diarrhea [7]. Maier and coworkers studied more than 1000 marketed drugs with respect to the growth of 40 representative intestinal bacterial strains. 24% of the tested drugs from all therapeutic classes inhibited the growth of at least one bacterial strain and thus, at least theoretically, altered the composition of the gut microbiome [7]. Among the drugs identified as altering the microbiome, certain classes, such as antipsychotics, were overrepresented. The authors refer here to “antibiotic-like side effects” that a number of substances exhibited [7].

One important group of drugs that causes diarrhea is, of course, antibiotics. The risk of antibiotic-induced diarrhea is higher with combination treatment than with monotherapy [8]. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea occurs in approximately 5-25% of patients treated with antibiotics [9–11]. They develop diarrhea within 2-20 days. Thus, the development of diarrhea with latency is also possible. Most antibiotic-associated diarrhea is associated with an alteration of the gut microbiome; it is bothersome but not of clinical significance. They also show spontaneous rebound when antibiotic therapy is stopped. However, again, it may take up to 3 or 4 weeks for bowel movements to return to normal.

However, Clostridioides-associated diarrhea may be present in 10-20% of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, or 0.5-5% of all antibiotic intakes [12]. Clostridioides difficile causes colitis by producing two typical toxins, A and B. These cause diarrhea by different mechanisms, one via direct epithelial cell damage and the other via a secretory mechanism. Clindamycin, broad-spectrum cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones are most commonly associated with Clostridioides difficile-associated colitis [12]. However, any antibiotic can lead to this clinical picture. The triggering mechanism is thought to be that antibiotics lead to the death of bacteria that produce a bile acid metabolite toxic to Clostridioides difficile. This allows Clostridioides difficile spores, which are found in the intestines of many people, to develop into bacteria capable of multiplying. The severity of diarrhea varies widely. Severe courses up to the formation of megacolon occur, but have become very rare for unknown reasons. Not all evidence of toxin A or B positivity requires treatment. The clinical picture and clinical severity are critical.

Importantly, in this context, there is evidence that such Clostridioides difficile-related colitis can be prevented by certain probiotics. This was shown again recently in a large cohort study in which the incidence of CDI was 0.66% that concomitant administration of Saccharomyces boulardii along with antibiotics could reduce CDI incidence [12]It was 0.56% in patients given Saccharomyces boulardii together with antibiotics and 0.82% in patients given antibiotics alone without the probiotic. This means that the risk for patients to suffer from colitis was significantly reduced with the administration of Saccharomyces boulardii , the odds ratio was 0.57 [12].

However, it should be noted that meta-analyses on the effect of probiotics as prevention of Clostridioides difficile infection are inconsistent. Not all probiotics seem to have the same effect. A 2018 meta-analysis suggests an effect of probiotics in principle, but concludes that specific probiotics have different effects [13].

At the end of the considerations on diarrhea as a drug side effect, it should be mentioned that even seemingly harmless food additives can have negative effects. Therefore, the question about complementary medications is also an essential part of the clarification of a new onset of diarrhea. Zackular and coworkers showed in 2016 that dietary zinc alters the intestinal microbiota in a way that makes Clostridioides difficile infections more likely to occur [14]. In an animal model, dietary zinc increased the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection and caused severe inflammation [14]. Whether these data are directly transferable to humans is questionable. However, it is important to note here that in individual cases, even seemingly harmless food additives should be included in the considerations.

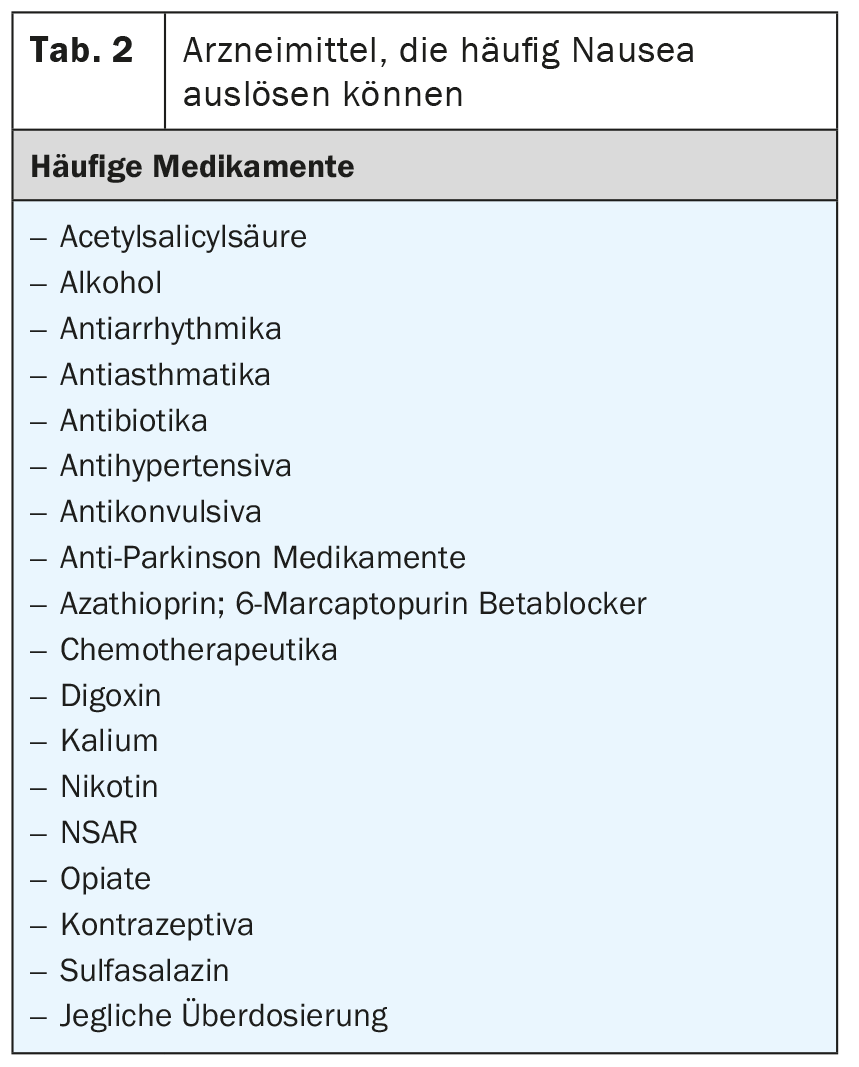

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are very common gastrointestinal side effects of drug therapy [15,16]. A list of medications commonly associated with nausea and vomiting is compiled in Table 2 . Of course, any overdose or withdrawal of a drug can acutely cause nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, in addition to drugs, there are a number of toxins from the environment that can trigger these symptoms. Overlays are possible. Concomitant drugs are also capable of inducing nausea [17].

Nausea is most commonly described after chemotherapy, of course. However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. In a recently published study looking at 241 patients, more than 20% reported chronic nausea and, in addition, more than 30% reported persistent diarrhea [18]. Interestingly, Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) was found in 54% of symptomatic patients [18]. In addition, bile acid malabsorption was found in 43% of patients [18]. We now know that SIBO and bile acid malabsorption often occur together.

Certainly, it is not always necessary to look for SIBO when nausea occurs after chemotherapy has been administered. However, if the nausea lasts longer, this investigation seems to make sense.

Gastrointestinal bleeding and pain

It is well known that inhibition of cyclooxigenase 1 and 2 by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) contributes to the development of gastric ulcers [19]. It is therefore not uncommon for a proton pump inhibitor to be administered in parallel with the NSAID in patients at risk from the outset [19]. However, it must be taken into account that PPI only prevent the formation of ulcers in the stomach. COX inhibition-induced -ulceration in the small or large intestine is not prevented:

Meiden and coworkers administered 75 mg diclofenac 2× daily for 14 days to 40 volunteers in 2005 and also gave 20 mg omeprazole 2× daily. Capsule endoscopy and calprotectin measurement were performed before and 2 weeks after diclofenac intake. Elevated calprotectin was seen in 75% of subjects [20]. Capsule endoscopy was pathologic in 68% of subjects, showing bleeding, ulceration, or erythema [20]. The lesions seen on capsule endoscopy could not be differentiated from Crohn’s disease lesions [20].

A similar study was published in 2010 by Fujimori and collaborators. Fifty-five healthy men received 75 mg of diclofenac per day for 2 weeks along with 20 mg of omeprazole as gastric protection. Again, capsule endoscopy was performed before and after NSAID treatment. Before NSAID treatment, 6 mucosal lesions were evident in 6 of 55 subjects (11%). [21,22]. After NSAID treatment, 636 lesions appeared in 32 of 53 subjects (60%) [21,22]. There were 115 de-epithelialized areas in 16 subjects, 498 erosions in 22 subjects, and 23 ulcers in 8 subjects [21,22]. The erosions appeared mainly in the upper small intestine, ulcerations mainly in the distal small intestine. These lesions occurred under gastric protection with a PPI, as mentioned [21,22].

Colon lesions have also been described with NSAIDs. Shibuya and coworkers showed in 2010 that NASR use significantly increased the risk of colonic mucosal lesions [23]. In both short-term and long-term use of NSAIDs, the authors found ulceration in up to 65% of all patients. However, some ulceration was also found in over one-third of those not taking NSAIDs [23].

The aspect of intestinal mucosal damage by NSAIDs becomes particularly important in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. In 2006, Takeuchi and coworkers showed that naproxen, diclofenac, and indomethacin can induce clinical relapse within 4 weeks of starting NSAID use in 10-25% of pa-tients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission [24]. In addition, they worsen the course of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the active phase [24]. Occasionally, the triggering of an episode is found even with the intake of a few tablets of NSAIDs, e.g. after tooth extraction or for the treatment of muscle pain after sports injury. Therefore, except for acetaminophen and novalgin, all NSAIDs are relatively contraindicated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and should be avoided. The self-help organization Crohn’s and Colitis Switzerland provides on its homepage a list of medications that can be considered relapse triggers in inflammatory bowel disease and should be avoided [25]. Selective COX-2 inhibitors, on the other hand, appear to be safe. At least for celecoxib, this was shown in a randomized, double-blind trial [26].

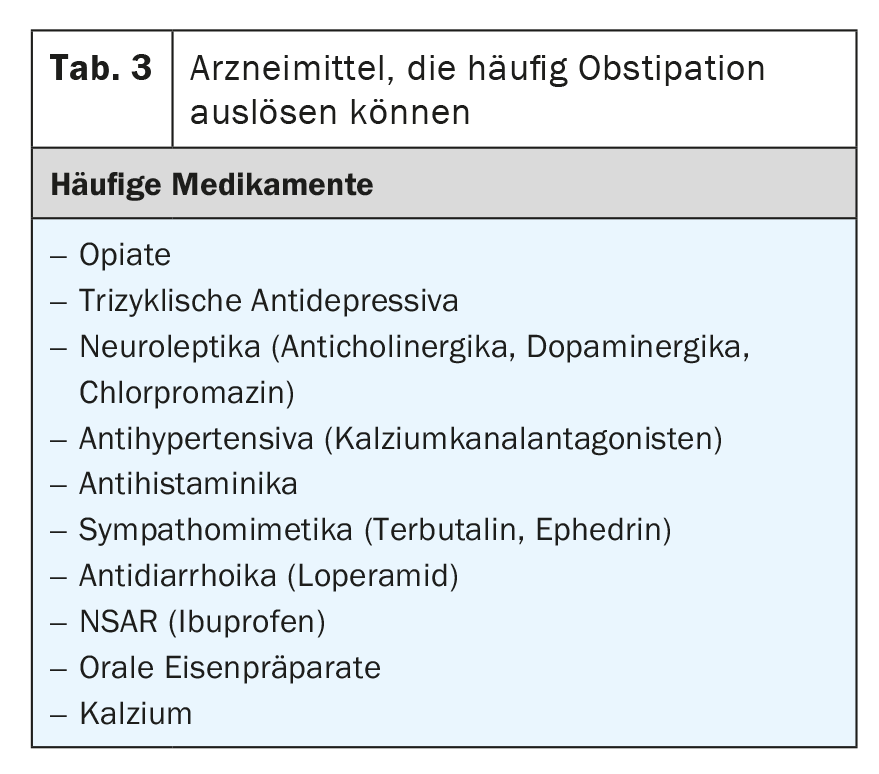

Constipation

As mentioned, constipation is also a very common medication side effect. However, it affects about 15% of the general elderly population in Europe in particular. It is often difficult to distinguish constitutional constipation from drug-induced constipation [27]. Nevertheless, the condition is important because patients with constipation have a significantly poorer quality of life and also incur significant health care costs compared to individuals without constipation.

A list of medications that can trigger constipation can be found in Table 3 . This includes only those substances that frequently to very frequently (1% to >10%) cause constipation. In principle, constipation can also be triggered by almost any medication, comparable to diarrhea.

Opiates and tricyclic antidepressants, as well as anticholinergics, are considered the strongest triggers of constipation [27]. The optimized effect of opiates often causes problems in the clinic, especially in tumor patients. In the USA, the so-called “Narcotic Bowel Syndrome” is now an entity for which there are dedicated specialists [28 –32].

Summary

Diarrhea, nausea, and constipation are among the most common drug side effects in gastroenterology. A medication history is therefore essential for the symptoms mentioned. A change in therapy should be given preference over symptomatic treatment of the side effects. Antibiotics and magnesium are very common triggers of diarrhea, but so are PPI or metformin. The gut-damaging effects of NSAIDs are often underestimated in times of PPI co-medication. However, PPIs only protect the stomach from ulceration. 24% of all non-antibiotic medications alter the microbiome and may contribute to changes in motility and fecal behavior. The actual medication is not always the problem: additives or accompanying substances (lactose) must be taken into account in the medical history. SIBO may be more common than thought; probiotic administration can probably reduce the risk after Clostridioides difficile infection.

Take-Home Messages

- Diarrhea, nausea, and constipation are among the most common drug side effects in gastroenterology. A medication history should always be taken when these symptoms reappear.

- A change in therapy should always be considered as a possibility.

- This is better and more sensible than symptomatic therapy of the side effects.

- Antibiotics and magnesium as well as PPI and metformin are common triggers of DID.

- Accompanying or filler substances such as lactose, rather than the actual pharmacon, can also cause side effects.

- The small and large bowel damaging effects of NSAIDs are often underestimated in times of PPI co-medication.

- Constipation as a medication side effect can severely impact quality of life and should always be taken seriously.

- Saccharomyces boulardii can prevent antibiotic-associated Clostridial colitis in about half of cases and should be used in high-risk patients.

Literature:

- Philip NA, Ahmed N, Pitchumoni CS: Spectrum of drug-induced chronic diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(2): 111-117.

- Hum SW, et al: Adverse Events of Antibiotics Used to Treat Acute Otitis Media in Children: A Systematic Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr 2019; 215: 139-143 e7.

- Garrison SR, et al: Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 9: CD009402.

- Alsalimy N, Madi L, Awaisu A.: Efficacy and safety of laxatives for chronic constipation in long-term care settings: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2018; 43(5): 595-605.

- Petticrew M, Watt I, Brand M.: What’s the “best buy” for treatment of constipation? Results of a systematic review of the efficacy and comparative efficacy of laxatives in the elderly. Br J Gen Pract 1999; 49(442): 387-393.

- Bril S, Shoham Y, Marcus J.: The ‘mystery’ of opioid-induced diarrhea. Pain Res Manag 2011; 16(3): 197-199.

- Maier L, et al: Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 2018; 555(7698): 623-628.

- Ma H, et al: Combined administration of antibiotics increases the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in critically ill patients. Infect Drug Resist 2019; 12: 1047-1054.

- Messacar K: Narrow-spectrum, compared with broad-spectrum, antibiotics equally effective with fewer adverse events. J Pediatr 2018; 196: 324-327.

- Mittermayer H: Diarrhea induced by antibiotics. Wien Med Wochenschr 1989; 139(9): 202-206.

- Roehr B: Antibiotics account for 19% of emergency department visits in US for adverse events. BMJ 2008; 337: a1324.

- Wombwell E, et al: The effect of Saccharomyces boulardii primary prevention on risk of Hospital Onset Clostridioides difficile infection in hospitalized patients administered antibiotics frequently associated with Clostridioides difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2020.

- Goldenberg JZ, Mertz D, Johnston BC: Probiotics to Prevent Clostridium difficile Infection in Patients Receiving Antibiotics. JAMA 2018; 320(5): 499-500.

- Zackular JP et al: Dietary zinc alters the microbiota and decreases resistance to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Med 2016; 22(11): 1330-1334.

- Parkinson J, et al: Application of data mining and visualization techniques for the prediction of drug-induced nausea in man. Toxicol Sci 2012; 126(1): 275-284.

- Bytzer P, Hallas J: Drug-induced symptoms of functional dyspepsia and nausea. A symmetry analysis of one million prescriptions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14(11): 1479-1484.

- Lacy BE, Parkman HP, Camilleri M.: Chronic nausea and vomiting: evaluation and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(5): 647-659.

- Andreyev HJN, et al: The FOCCUS study: a prospective evaluation of the frequency, severity and treatable causes of gastrointestinal symptoms during and after chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2021; 29(3): 1443-1453.

- Hirschowitz BI: Minimizing the risk of NSAID-induced GI bleeding. Cleve Clin J Med 1999; 66(9): 524-527.

- Maiden L, et al: A quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopy. Gastroenterology 2005; 128(5): 1172-1178.

- Fujimori S, et al: Distribution of small intestinal mucosal injuries as a result of NSAID administration. Eur J Clin Invest 2010; 40(6): 504-510.

- Fujimori S, et al: Prevention of traditional NSAID-induced small intestinal injury: recent preliminary studies using capsule endoscopy. Digestion 2010; 82(3): 167-172.

- Shibuya T, et al: Colonic mucosal lesions associated with long-term or short-term administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12(11): 1113-1121.

- Takeuchi K, et al: Prevalence and mechanism of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced clinical relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4(2): 196-202.

- https://5f385573-02c2-4d44-bae0-195fc02c0ec5.filesusr.com/ugd/4cd18c_15f0fcbe982d4e549ff5667302c28aa5.pdf.

- Sandborn WJ, et al: Safety of celecoxib in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission: a randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4(2): 203-211.

- Wanitschke R, Goerg KJ, Loew D: Differential therapy of constipation–a review. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003; 41(1): 14-21.

- Kong EL, Burns B.: Narcotic bowel syndrome, in StatPearls 2021: Treasure Island (FL).

- Szigethy E, Schwartz M, Drossman D.: Narcotic bowel syndrome and opioid-induced constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16(10): 410.

- Buckley JP, et al: Prevalence of chronic narcotic use among children with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13(2): 310-315 e2.

- Azizi Z, Javid Anbardan S, Ebrahimi Daryani N: A review of the clinical manifestations, pathophysiology and management of opioid bowel dysfunction and narcotic bowel syndrome. Middle East J Dig Dis 2014; 6(1): 5-12.

- Kurlander JE, Drossman DA: Diagnosis and treatment of narcotic bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11(7): 410-418.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(8): 6-11