Physicians have a central role to play with regard to tobacco cessation. Smokers need to be identified in the consultation so that they can be referred to appropriate treatment. The combination of counseling and drug support promises the greatest likelihood of success.

The starting position is clear: smoking endangers health! Not only smokers themselves are affected, but also their environment. It has also been proven that stopping smoking makes sense for our patients far beyond the health aspect. Many smokers would like to quit smoking. A recent publication from the Centers for Disease Control examined data from smokers in 28 countries. The prevalence of smoking averaged approximately 23%, with approximately 43% of smokers having had a quit attempt within the previous 12 months [1]. It remains sobering that only about 2-3% of spontaneous smoking cessation attempts are successful [2]. In contrast, it is encouraging that medical advice to stop smoking can double this result (Relative Risk, RR: 1.66 [95% confidence interval, CI 1.42-1.94]) [3].

Our central role as physicians is characterized by identifying smokers in the consultation and then providing them with appropriate counseling or care. This is especially true in light of the fact that about 80% of smokers see a doctor within a year.

Achieving freedom from smoking often poses major challenges for both our patients and us: There are major and minor hurdles to overcome along the way. This article aims to provide practicing physicians with an overview of the process and therapeutic approaches of smoking cessation and to point out possible solutions to any difficulties.

Guidelines Procedure Stop Smoking Counseling

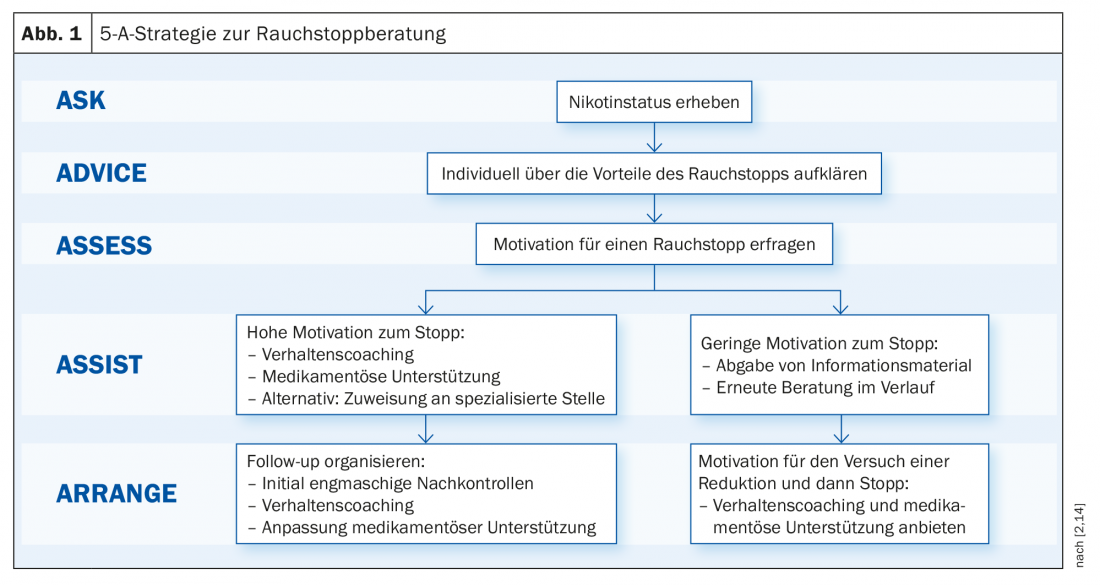

Different guidelines exist for approaching smoking cessation counseling in primary care. There is agreement on the need to educate smokers about the importance of quitting and to offer supportive measures such as medications and counseling regarding behavior change. Figure 1 summarizes the “5-A strategy” for smoking cessation as recommended in the 2012 and 2016 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for Cardiovascular Prevention.

The steps “Ask – Advice – Assess” are also called brief intervention. They do not require a great deal of time, but they do form the basis for further treatment. Specifically, it includes the following steps:

- Ask: Identify smokers.

- Advice: educate smokers individually about the health aspects of their tobacco use.

- Assess: elicit motivation to quit smoking.

The latest expert consensus from the American College of Cardiology goes a step further and recommends offering treatment options (behavioral coaching and medication) directly, or to prescribe if the patient agrees [4].

The consultation

The goal of the counseling session is to help patients change their behavior from smoker to non-smoker. For this purpose, the technique of “motivational interviewing” has proven to be an effective tool [5]. This style of counseling is based on encouragement and support, rather than evidence and persuasion. In this way, a positive interpersonal atmosphere is sought, which prepares the ground for behavioral change.

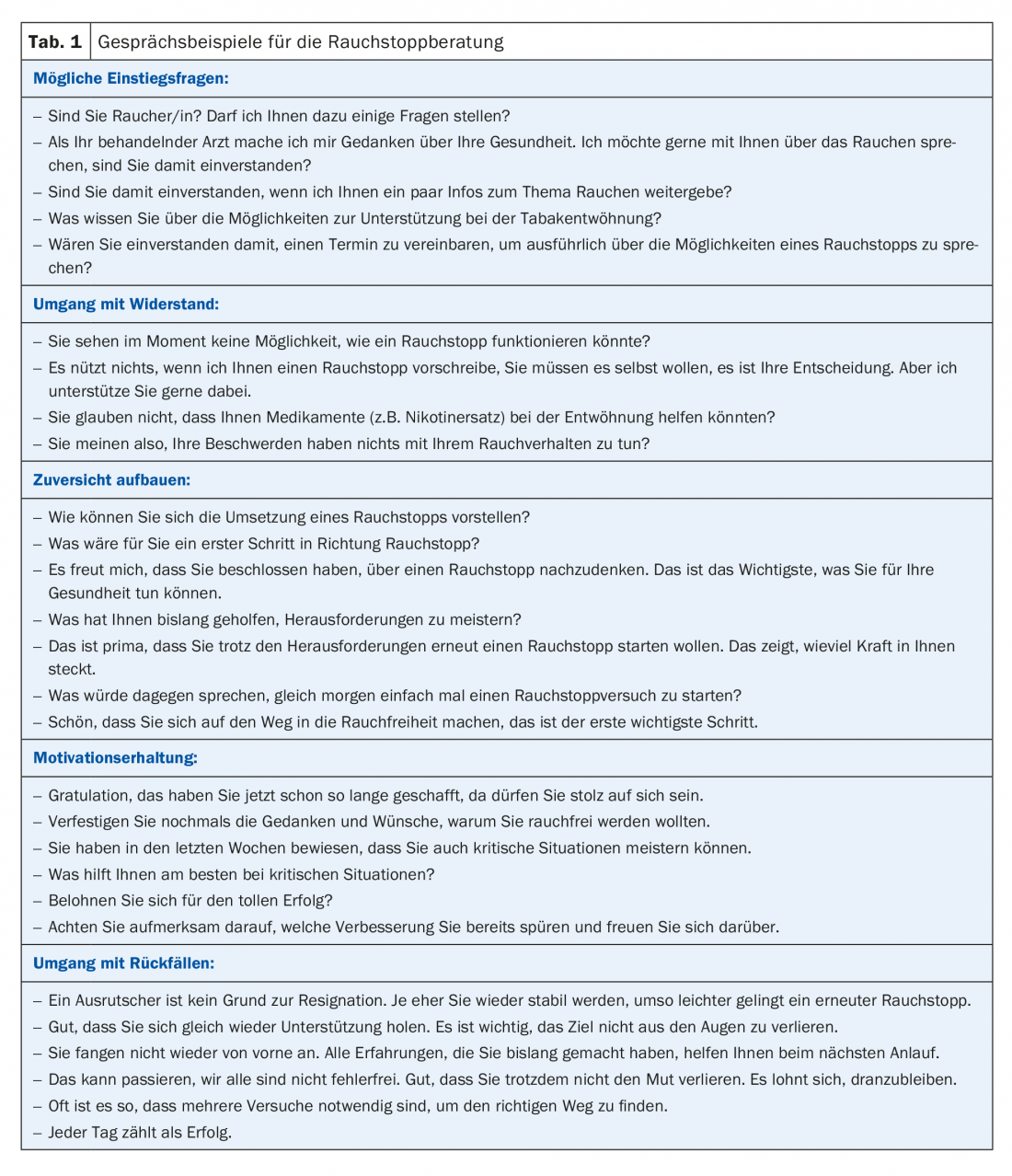

This includes the basic principles of approaching the patient in an empathetic and supportive manner, meeting him on an equal footing and accepting his point of view. Contrary to common belief, deterrent or anxiety-inducing statements generally have little effect and are more likely to impair the doctor-patient relationship. It is also important not to fight resistance with counter-arguments, but rather to understand this as a signal that the patient is announcing his limits to us here. It is then helpful to support the patient in specifying his ambivalences in order to move him forward in decision-making. The attending physician has the role of understanding the patient’s point of view – without, however, always having to endorse it. It is advisable to highlight individual benefits of quitting smoking and avoid accusations or judgmental statements about behavior. The motivation for change lies within the patient and should be elicited and strengthened. Conversation examples for dealing with resistance can be found in Table 1.

The way we start the consultation often determines whether we can have an open conversation. Thus, the opening of the conversation has a significant role to play (see Opening Questions Table 1).

Smoking cessation attempts often end in relapse despite a great effort of will and are therefore a frustrating endeavor for many of our patients. Promoting motivation and confidence is thus an important component of counseling (tab. 1) . The targeted explanation that sustained success is usually preceded by several attempts is often able to counteract frustration. It can also be helpful to explain the effects of nicotine and the associated potential for dependence, and to address possible withdrawal symptoms. This also promotes readiness for complementary drug treatment.

Regular follow-up visits to support weaning should be part of any treatment. The content is to work out coping strategies to maintain abstinence in order to counteract relapse. Potential risk situations should be discussed in order to anticipate them and to develop behavioral strategies for appropriate situations (avoid triggers, wait, distract, resist, etc.). Medication efficacy should also be reviewed and adjusted if necessary. The following schedule is recommended for follow-up appointments: 1, 2, 4, 8 weeks; 3, 6, 12 months.

Talk is silver – coaching and medication are gold

A good counseling session is a fundamental pillar of patient management in the context of smoking cessation. As mentioned at the outset, the combination of counseling and medication support is superior to a counseling alone but also to a medication alone approach with regard to the effectiveness of smoking cessation. Therefore, the counseling session and drug treatment should be offered in combination whenever possible.

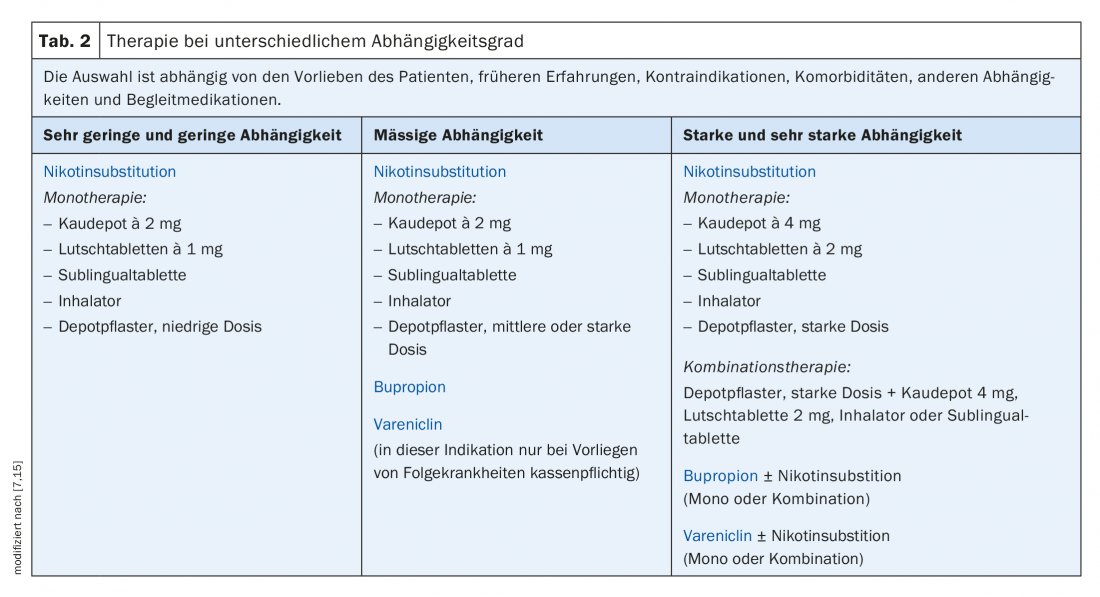

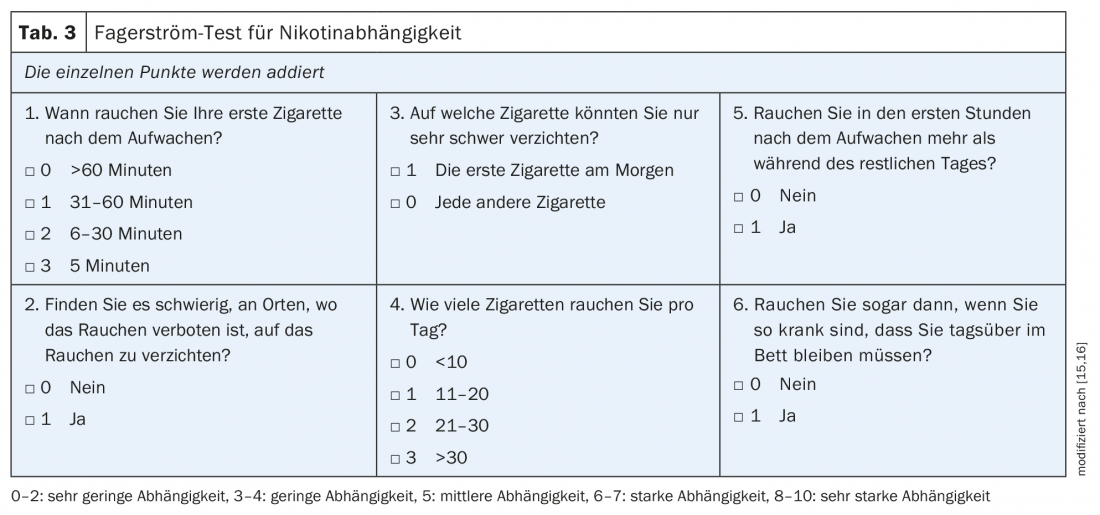

Three groups of medications are available as pharmacological aids for smoking cessation, namely nicotine replacement products (NEPs), varenicline, and bupropion. All three drug groups are more effective than placebo in achieving freedom from smoking after six months [4]. The choice of product depends on the strength of the dependency, which can be determined by means of the Fagerström test (Tab. 2/Tab. 3), and on the user’s preference. Especially with NEP, it is important to choose the dosage high enough and to apply the therapy for a sufficiently long time.

Nicotine Replacement Products: NEPs are available in a variety of dosage forms. A distinction is made between short-acting products, such as chewable patches or inhalers, and long-acting dosage forms in the form of depot patches. The combination treatment, consisting of a long-acting basic therapy (depot patch) supplemented with a short-acting demand therapy, achieves the highest efficacy [6]. The absence of absolute contraindications is a significant advantage of NEP.

Varenicline: This drug exerts its dual mode of action at the nicotinic receptor in the brain. The partial agonist results in partial stimulation of the receptor, leading to a reduction in withdrawal symptoms. At the same time, there is also an antagonistic effect, which manifests itself in the absence of an effect with simultaneous nicotine consumption. The patient may continue to smoke during the first two weeks of treatment and many patients have an altered, less positive smoking experience during this time. The most common side effects are gastrointestinal discomfort, such as nausea. This can be counteracted by slowly increasing the dosage or by taking the drug together with a small meal. Varenicline should not be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. In terms of efficacy, varenicline is equivalent to adequate combination therapy of short- and long-acting NEPs and superior to bupropion or mono-nicotine replacement therapy [6].

Bupropion: this atypical antidepressant can also be used to support smoking cessation. Its action is via central reuptake inhibition of dopamine and norepinephrine. Compared to the two substance classes mentioned above, the less favorable side effect profile, an increased interaction potential with co-drug, but also a reduced efficacy should be noted [6].

Table 2 shows a practical overview of the use of the drugs. For more information regarding the scope, please refer to the Swiss Recommendations for Tobacco Cessation [7,8] and the compilation “Medical Smoking Cessation Counseling” [9].

For tobacco-dependent adults who are motivated to quit smoking and receive the support of a healthcare professional to do so, health insurance covers a twelve-week treatment with varenicline and a seven-week treatment with bupropion, provided that either a secondary tobacco disease or a severe nicotine dependence (Fagerström test ≥6) is present. In the event of a relapse, health insurance will not pay for renewed medication costs for at least 18 months.

If motivation is lacking: If there is no willingness to stop smoking, we can hand out information brochures and obtain consent to bring up the subject again at a later time. A brief intervention is also considered a success if it results in the development of awareness of the problem or consideration of behavior change in the foreseeable future.

For patients who do not yet want to quit but are willing to reduce their cigarette consumption, we can nevertheless start drug treatment on a trial basis. A study of the effect of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients willing to reduce cigarette consumption demonstrated the following: 24 weeks of varenicline significantly increased smoking cessation rates compared with placebo at one year (27.0% in the varenicline group vs. 9.9% in the placebo group; Risk Difference, RD: 17.1%. [95%-KI 13,3–20,9%]; RR: 2.7 [95%-KI, 2.1-3.5]) [10]. Similar results were already shown in 2008 in a meta-analysis for the use of NEP [11]. Thus, even in smokers without a high motivation to quit smoking, probationary drug treatment can make sense. This more proactive approach to medication use is also currently recommended by the American College of Cardiology [4].

In addition, smokers should be sensitized with regard to creating a smoke-free environment for relatives and especially children (keyword: smoke-free home, smoke-free car).

By no means all patients achieve the goal of sustained tobacco cessation. Whenever possible, we should use a relapse to further motivate patients to quit smoking (tab. 1). Relapses can help to identify risk situations and to work out strategies for coping with a similar situation the next time.

A common phenomenon is that patients manage to reduce cigarette consumption significantly, but then get stuck with a small number of cigarettes. In this situation, the medication can be expanded, for example, through combination therapy. In particular, varenicline can be supplemented with NEP (patches, short-term routes of administration) or bupropion with NEP [4].

As a “last resort” after multiple frustrating attempts to quit smoking or if there is absolutely no motivation to stop smoking, the use of an electric cigarette in the sense of a “harm-reduction” can be useful. However, care should be taken to make a complete switch to truly achieve damage reduction. In the past year, several studies have shown that even the consumption of a small number of conventional cigarettes per day carries a substantial health risk. According to a paper by Hackshaw et al. the cardiovascular risk of smoking only one cigarette per day is still half that of smoking 20 cigarettes per day [12]. Accordingly, the mere reduction of conventional smoking shows less benefit than assumed, especially with regard to cardiovascular complications. Another paper showed that increased mortality can also be demonstrated in occasional smokers who consume less than one cigarette per day compared with nonsmokers [13].

Take-Home Messages

- Extensive evidence exists regarding the potential of smoking to endanger health, but also regarding the health benefits of quitting smoking.

- We physicians have a central role to play in identifying smokers as such in our consultations, and then directing them to appropriate treatment.

- Whenever possible, a combination of counseling and medication support should take place, as the combination is superior to a stand-alone treatment approach in terms of effectiveness of smoking cessation.

Literature:

- Ahluwalia IB, et al: Current Tobacco Smoking, Quit Attempts, and Knowledge About Smoking Risks Among Persons Aged ≥15 Years – Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 28 Countries, 2008-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(38): 1072-1076.

- Piepoli MF, et al: 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016; 37(29): 2315-2381.

- Stead LF, et al: Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (5): CD000165.

- Barua RS, et al: 2018 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Tobacco Cessation Treatment: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018.

- Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R: Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(3):CD006936.

- Cahill K, et al: Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (5): CD009329.

- Cornuz J: Tobacco cessation, part 2: recommendations for daily practice. Switzerland Med Forum 2004; (4): 792-805.

- Cornuz J: Tobacco cessation, part 1: How it works and what it brings. Switzerland Med Forum 2004; (4): 764-770.

- Cornuz J, Jacot Sadowski I, Humair JP: Physician smoking cessation counseling. The documentation for practice. 3rd ed. 2015.

- Ebbert JO, et al: Effect of varenicline on smoking cessation through smoking reduction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 313(7): 687-694.

- Wang D, et al: ‘Cut down to quit’ with nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation: a systematic review of effectiveness and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2008; 12(2): iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-135.

- Hackshaw A, et al: Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 2018; 360: j5855.

- Inoue-Choi M, et al: Association of Long-term, Low-Intensity Smoking With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(1): 87-95.

- Perk J, et al: European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012; 33(13): 1635-1701.

- Burkard TH: Smoking cessation. Information for daily practice. HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8(11): 22-27.

- Heatherton TF, et al: The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991; 86(9): 1119-1127.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(2): 27-32