Year after year, the available accident statistics show us very clearly: sporting activities cause with astonishing regularity about 300,000 accidents, the majority of which fortunately are not too serious.

Whether contusion or bruise, strain or sprain, in all these frequently occurring mostly favorable sports injuries, the pathophysiological moment is identical: due to the damaging unexpected uncoordinated application of force, there is damage to one or several types of tissue (capsule, tendon, muscle, ligaments, even cartilage and bone) with release in the milieu of damaged cells from these affected structures, as well as blood from the local vessels that are also injured (Fig. 1). These “foreign substances” automatically trigger a chain of reactions: wound healing. This healing process begins at the time of injury in all traumas.

Support healing process

With a treatment that specifically intervenes in the healing process, regeneration can be promoted and the healing time shortened. It is therefore important to move away from purely symptomatic treatments towards therapies that specifically support the healing process. To do this, it is necessary to understand the different phases of the processes.

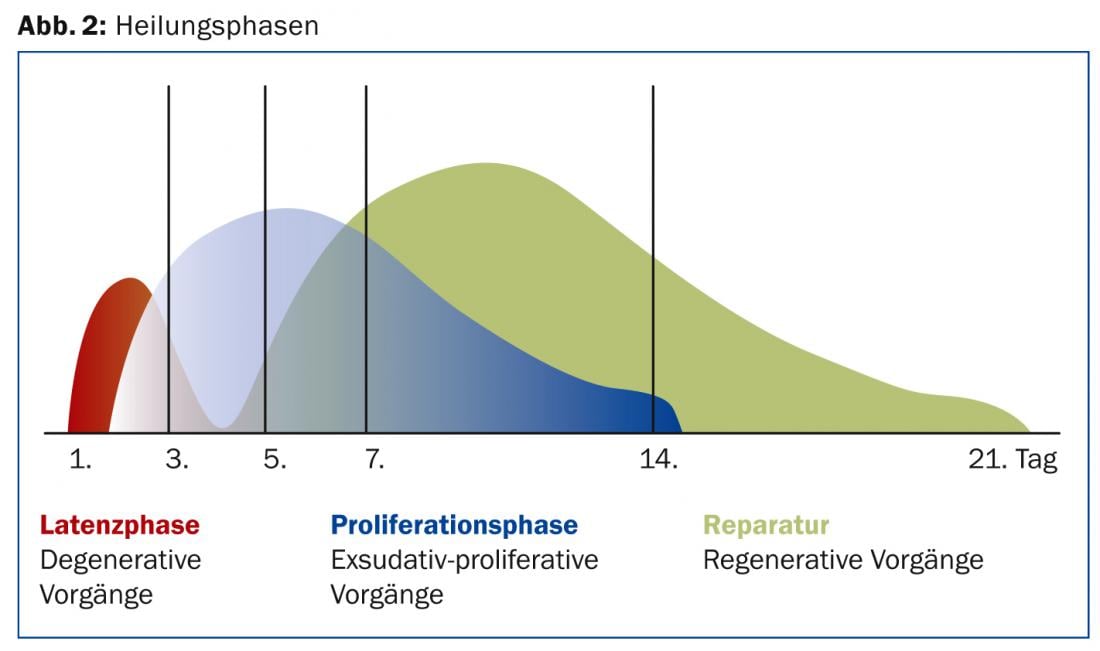

The healing phases are basically the same for each tissue and differ only in some tissue-specific features. In the first catabolic phase of healing, which is characterized by inflammation and wound cleansing, there is initially a hematoma consisting, among other things, of a fibrin clot, the structure of which is important for the further course. The cells subsequently need this fibrin to regenerate from it and form new extracellular matrix. In the following anabolic proliferation phase, the tissue cells, i.e. fibroblasts and keratinocytes, already start working again to form tissue. Finally, the basic substance of the tissue, i.e. the matrix, is formed in the repair phase (Fig. 2).

What is the time course?

The individual phases of the healing process occur at different times. These three phases do not run strictly one after the other, but overlap. Their duration is also variable and varies from individual to individual. Data from the literature range from 16 to 50 weeks.

The hematoma forms after only a few seconds to a few minutes. A few hours to days later, fibroblasts become active and change the tissue. The regeneration phase begins about a week after the initial trauma and can last up to a year, depending on the tissue type. Different cell types play different roles in the different phases of healing. All the processes involved are closely interconnected. The healing phases are not simple linear processes. Rather, they are intertwined and cannot be separated in time or space. The duration of the individual healing phases often depends on the size of the hematoma caused by the injury. Cells of the immune system with its network of cytokines are also involved in all processes of wound healing in different ways. These components of the immune system stimulate tissue regeneration by controlling cell growth and stimulating differentiation, cell metabolism and protein synthesis. Interleukin-1 and TNF-X are particularly active, but growth factors such as TGF-β also play an important role by inhibiting pro-inflammatory T cells. TGF-β stimulates tissue regeneration by stimulating fibroblast activity.

Despite this highly subtle process, this tissue healing can be negatively affected by several factors. These include nicotine use, initiation of therapy, age, and NSAIDs.

Phase-adapted therapy concept makes sense

A so-called phase-adapted therapy concept has proven very successful. In the early phase (inflammatory stage), the focus is on controlling post-traumatic swelling. For this purpose, the PECH scheme (P=pause, E=ice, C=compression, H=hyperposition) is applied.

These well known but unfortunately too often forgotten simple cheap measures are not only useful on the sports field or in the immediate first aid and moreover still efficient, but also subsequently as part of the medically prescribed further treatment.

We take a critical view of the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as these medications hinder the naturally programmed healing process on the injured tissue. If absolutely desired, then topical applications such as patches will suffice.

In case of ligament injury (knee, OSG), the patient can be immediately fitted with an orthosis. Relief with canes may also be useful on a case-by-case basis. After a few days of such immobilization, the area is further stabilized with the orthosis and weight bearing is gradually reestablished over two to four weeks.

Semirigid orthoses or tape dressings are suitable for the proliferation phase.

In the regeneration phase, controlled mechanical loading promotes proper orientation (alignment) of collagen fibers. This is where physiotherapy, although it can be prescribed from the beginning, will have its main effect.

Healing completed – what now?

After healing is complete, support of the injured area with a bandage is recommended, especially for patients who exercise regularly. To meet the requirements of phase-adapted rehabilitation, bandages can also be used whose stability can be gradually downgraded. Accompanying sensorimotor training is desirable and should begin after about four weeks.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(4): 4-5