The vast majority of care for dementia patients is provided by family members. In over 90% of cases, care is provided by women, and over 60% live in the same household as the person with dementia. Family caregivers are often burdened, especially by the progression of the disease and the associated helplessness, but also by personal limitations. Communicating the diagnosis as early as possible and providing information about the disease are essential. There are many relief options for family caregivers, which they need to be educated about. Psychotherapeutic methods are particularly helpful, which, in addition to providing information and modifying the problematic behavior in relatives, also include the emotional components and address the individual stress situation. Psychotherapeutic interventions may also need to be combined with antidepressant-anxiolytic drug therapy.

Dementia, along with depression, is the most common neuropsychiatric disorder of aging. Currently, the number of patients with dementia in Switzerland is about 110,000. The number of new cases is estimated to be up to 25,000 per year, with an increase to up to 220,000 individuals in 2030 [1]. The prevalence of dementia increases with age: only 1.4% of 65- to 69-year-olds are affected, compared with 32% of those over 90 [2]. The most common dementia is Alzheimer’s type dementia, followed by vascular dementia. There is an increasing number of patients suffering from Lewy body dementia, which now accounts for up to 30% of all patients diagnosed with dementia [3,4]In addition to the cognitive impairment, which is associated with the reduction of everyday functionality, dementias are characterized by behavioral disorders and psychopathological syndromes (behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, BPSD), which contribute primarily to the burden of the social environment and thus the relatives. [5,6].

For the primary dementing diseases (neurodegenerative and vascular diseases), no curative treatments are available, although drug and non-drug interventions can favorably influence the course of the disease. In contrast, BPSD can be well treated by specific drug and non-drug therapeutic interventions in many cases [7]. The treatment as a whole is more promising the earlier it is started.

In subcortical dementias, such as Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementias, motor dysfunction is added to the loss of cognitive abilities and behavioral disturbances, so care for this group of patients involves an additional aspect.

Need for care and family caregivers

The overall need for long-term care increases from 2% in the 65-69 age group to 14% in the 85-89 age group. The exponential increase in the need for long-term care from the age of 70 is largely determined by dementia [2]. Due to the further increase in dementia, elderly care will face a major challenge in the coming years. Both the knowledge about dementia diseases, their symptomatology and their course, as well as the knowledge about possible relief is therefore of great relevance. Partners and children are the largest group of caregivers. Recently released figures show that 90% of family caregivers are female, with an average age of 56. 71% of them cared for their parents, and 65% lived with their parents [6].

Factors influencing the burden on relatives

The burden on caregivers depends on the severity of the disease [2]. With increasing disease duration, progression of cognitive decline, and increase in behavioral disturbances, the amount of care required for Alzheimer’s dementia increases. In contrast, vascular dementias require more care in the early stages of the disease, but less care in the later stages than Alzheimer’s dementia [8]. In particular, non-cognitive symptoms, and of these, apathy and depressive symptomatology, contribute to caregiver burden, whereas for cognitive symptoms this relationship is not so clear [9]. In the Alzheimer’s patients, a higher burden of care among the relatives is mainly related to the impairment of social behavior, while in the patients with vascular dementia it is more the impairment of memory and disruptive behavior [2]. From this it can be deduced that especially in frontotemporal dementias the burden is even higher, and in the case of frontotemporal symptoms in atypical Parkinson’s syndromes (based on tauopathies) it increases even more. A higher burden on caregivers has also been found for Lewy body dementia, where primary and secondary dementia symptoms (cognitive impairment, behavioral impairment) are compounded by motor impairment [10].

Other influencing factors are also involved in the development of the burden on relatives. These can be divided into unchangeable contextual conditions as well as changeable factors [11]. Invariant contextual conditions include age and gender, health status, generational relationship, socioeconomic circumstances, and cultural background. It is well known that women are more heavily burdened by the caregiving role than men. This applies to spouses as well as daughters and daughters-in-law.

Other factors associated with increased stress include:

- Care of a spouse (compared to care of a parent).

- Higher age of the caregivers

- Lower income

- Physical and mental illnesses of the caregivers

- Shared household with the person to be cared for

- Effort required for the supply

Another area that intensifies the burden on family members is the personal limitations associated with caregiving. Conflicts arise here between the demands of caregiving and the demands of work, especially family, but also the desire for leisure activities and social relationships with friends. This leads many relatives to neglect their own needs to the point of neglecting their own health [11,12].

Difficulties and tensions also arise from the change in the relationship with the partner or parent, which is associated with a change in the assumption of roles.

The dementia patient is increasingly subject to a change in personality, the father or spouse is no longer as he once was. He may show reactions and behaviors that were not known in him, but which are not an expression of the personality, but of the disease. Recognizing this and also accepting it is a basic element of successful care.

Despite these interpersonal stress factors, many relatives succeed in creating a climate of closeness and familiarity and thus in maintaining the emotional bond with the patient [11]. The better the relationship between the partners or with the affected parent before the illness, the more successful this will be [13].

These multiple stresses faced by the family caregiver can lead to increasing exhaustion, both physical and psychological. In particular, the experience of helplessness, both in influencing the disease process and within everyday situations, the often missing appreciation (which the affected person can no longer give or only to a limited extent) and the lack of support from the social environment represent a burnout constellation. Without correction, this can lead to a state of exhaustion (in the sense of a burnout syndrome) and ultimately also to depression or anxiety disorder or to physical illnesses (especially cardiovascular diseases) [14].

Factors, which affect this stress process, are – in the sense of the stress model of Lazarus – the subjective evaluation of the situation, in which the member is, as well as the availability of coping strategies, in order to master the requirements [3,4]. Successful coping first requires acceptance of the situation and the burden at hand, then planning ahead and seeking concrete help. Stress increases when support from other family members, the social environment, or care providers is not available, or support that is available is not perceived as helpful. Avoidance and denial have a negative effect and support a developing burnout process. In particular, the acceptance that the relative’s illness is irreversible and that the formerly equal partner can no longer see eye-to-eye and is increasingly changing in his or her ability to cope with everyday life is a basic prerequisite for coping with the stresses and strains in the role of the family caregiver. It has proven to be very helpful if the family caregivers succeed in experiencing their caregiving activity as meaningful, which gives them a purpose in life. Seeking only emotional support is not enough.

Interventions to support family caregivers.

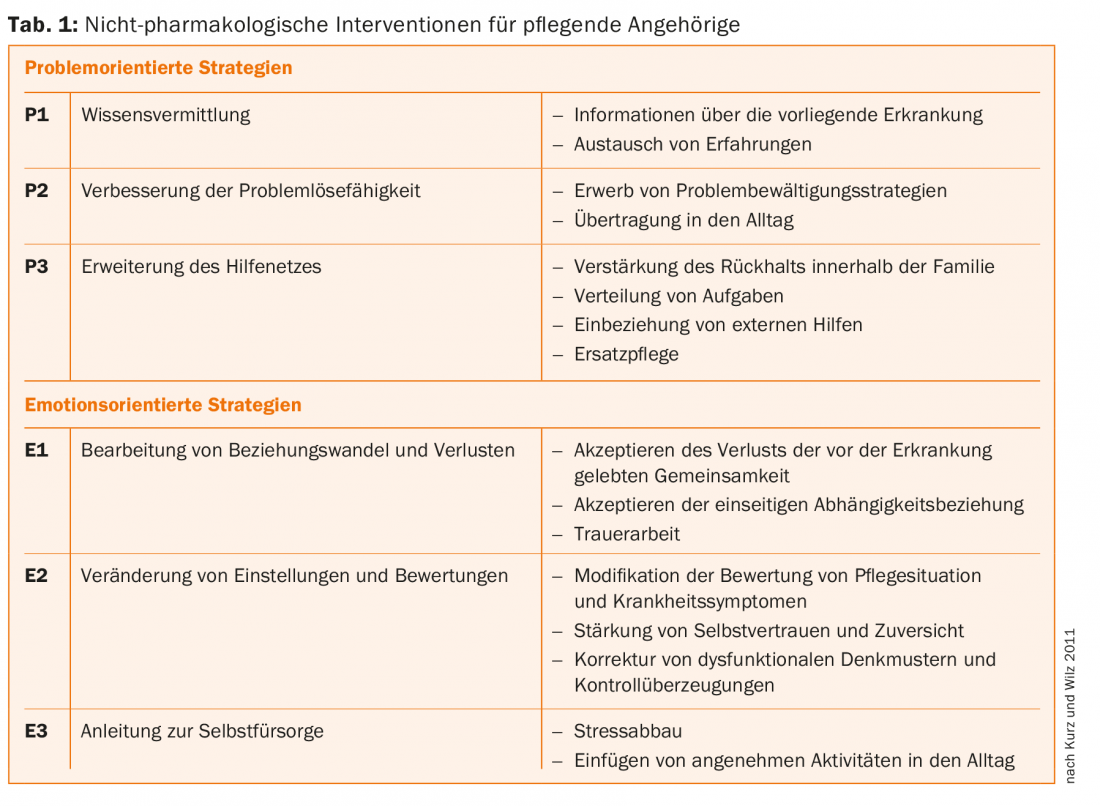

A number of interventions have been developed to reduce the burden on family members – due to the multiple influencing and originating factors. However, there has been little systematization and controlled evaluation of these to date. A basic distinction can be made between problem-oriented and emotion-oriented measures (Tab. 1) [11].

The primary purpose of the problem-oriented measures is to reduce the stress intensity of the objective circumstances, to modify the attitudes of the family caregiver, and to promote necessary coping strategies. Emotion-focused strategies focus on addressing negative feelings as well as correcting existing dysfunctional beliefs to increase confidence and well-being. Problem-oriented interventions are used much more frequently than emotion-oriented techniques [11]. One reason for this could be that there are not (yet) enough psychotherapeutic services available for the care of relatives of dementia patients. Expanding the help network, changing attitudes and evaluations, and dealing with role change and loss due to illness have been mentioned little in the work published to date. These elements, which are still underrepresented in family support, could be addressed as part of a complex, cognitive-behavioral therapy approach.

Huis et al. indicate the need to teach the relatives of dementia patients to self-manage, i.e., under the guidance of professionals, to strengthen the skills that relatives need to successfully cope with symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes [15]. In addition to the demands of caring for the patient, family members must also manage their own problems, such as the demands of family and work.

Therefore, as “informal caregivers,” family members often need the support of professional caregivers/treaters such as physicians, psychologists, and nurses. These provide support for decisions and the actions in everyday life. Five categories of self-management can be described [16]:

- Information about the disease (dementia)

- Relationship with the family

- Maintaining an active lifestyle

- Psychological well-being

- Availability of techniques to cope with memory impairment.

Evaluation of these categories in a meta-analysis found that, in particular, interventions that provided guidance on improving psychological well-being as well as information about the illness were of great effectiveness in terms of successful coping with the caregiving role [15,17]. Particularly effective were interventions that markedly reduced stress in relatives’ perceptions (regardless of the method used) and cognitive interventions that promoted relatives’ social support and improved their relationship with the patient and overall quality of life [15]. No effects were described for the category “maintenance of an active lifestyle,” although it should be noted that this intervention was not explicitly reported in the present work. Longer (more than 8 weeks) and more intensive (more than 16 hours) interventions were more effective than shorter ones. Psychoeducation seems to be an indispensable building block in intervention programs, as almost all effective programs contained psychoeducational elements. In addition, psychoeducational groups had better outcomes in psychological well-being and depression [12,15].

However, interventions aimed purely at imparting knowledge only slightly increase the psychological well-being as well as the quality of life of family caregivers [11]. Nevertheless, information about the disease is of great importance, especially the explanation that a certain behavior of the affected person is directly related to the disease itself and less determined by the person of the counterpart. Both family members and case managers cited the earliest possible notification of the diagnosis as particularly important in terms of what needs to be organized [18]. Overall, evidence from this work suggests that a complex cognitive-behavioral therapy program that incorporates both problem- and emotion-focused intervention strategies and is designed as a long-term therapy has the greatest effectiveness on family members’ health. In one study, the use of such a program was shown to improve the relationship between the caregiver and the person being cared for and also to delay the institutionalization of the patient.

A controlled study is currently being evaluated at the University Hospital in Zurich using a complex cognitive-behavioral therapy program [12]. One can be curious about the results. In Switzerland, there is already a wide range of information about the disease and psychosocial support; the Alzheimer Society Switzerland (www.alz.ch) and its regional representatives provide this information. Nearly all memory clinics and the larger gerontological psychiatry units offer family counseling. At some memory clinics, there are also therapeutic groups for family members, where many of the elements mentioned above are worked on for successfully coping with the major challenges of caring for dementia patients.

Conclusion

The vast majority of care for dementia patients is provided by family members. In over 90% of cases, care is provided by women, and over 60% live in the same household as the person with dementia. The family caregiver is burdened in many ways, primarily by the progression of the disease and the associated helplessness, but also by personal limitations, financial losses and the conflict between caring for the demented relative and the rest of the family.

Interventions must include communication of the diagnosis as early as possible, as well as information about the disease, and a constant point of contact must be available. There are many relief options for family caregivers, which they need to be educated about. Psychotherapeutic methods are particularly helpful, which, in addition to providing information and modifying the problematic behavior in relatives, also include the emotional components and address the individual stress situation of the relatives. These complex psychotherapeutic programs must be used if the relatives have already developed a burnout syndrome; if necessary, the psychotherapeutic interventions must also be combined with antidepressant-anxiolytic drug therapy.

Literature:

- Swiss Alzheimer’s Association: For Relatives. How can we support you?, 2016. www.alz.ch/index.php/fuer-angehoerige.html

- Rainer M, et al: Family caregivers of dementia patients: stress factors and their impact. Psychiatr Prax 2002; 29: 142-147.

- Zaccai J, et al: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence studies of dementia with Lewy bodies. Ageing 2005; 34(6): 561-566.

- Mollenhauer B, et al: Dementia with Ley bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Dt. Ärzteblatt 2015; 102(39): 684-689.

- Feast A, et al: Behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia and the challenges for family carers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2016 May; 208(5): 429-434.

- Storti LB, et al: Neuropsychiatric symptoms of the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease and the family caregivers’ distress. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2016 Aug 15; 24: e2751.

- Savaskan E, et al: [Recommendations for diagnosis and therapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD)].

- Vetter PH, et al: Vascular dementia versus dementia of Alzheimer’s type: do they have differential effects on caregivers’ burden? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999; 54(2): S93-98.

- Donaldson C, et al: The impact of the symptoms of dementia on caregivers. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170: 62-68.

- Boström F, et al: Patients with dementia with lewy bodies have more impaired quality of life than patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2007; 21(2): 150-154.

- Kurz A, et al: The burden of caring relatives in dementia. Conditions of occurrence and possibilities for intervention. Neurologist 2011; 82: 336-342.

- Forstmeier S, et al: Cognitive behavioural treatment for mild Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers (CBTAC): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16: 526.

- Steadman PL, et al: Premorbid relationship satisfaction and caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2007; 20(2): 115-119.

- Hemmeter U: Burnout overlap of Diagnosis. In: Burnout for experts: Prevention in the context for Living and working. Springer Science and Media, New York, 2012.

- Huis In Het Veld JG, et al: The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self-management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatr 2015; 15: 147.

- Martin F, et al: Perceived barriers to self-management for people with dementia in the early stages. Dementia (London) 2013; 12(4): 481-493.

- Vernooij-Dassen M, et al: Cognitive reframing for carers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 11: CD005318.

- Khanassov V, et al: Family Physician-Case Manager Collaboration and Needs of Patients With Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med 2016 Mar; 14(2): 166-177.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(5): 8-11.