Venous ulcers are based on chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). Compression therapy directly combats congestion and edema and is therefore the most important component of successful treatment. The local therapy depends on the amount of exudate, pain level or wound margin damage, among other factors.

A wound is the separation of the tissue context on external and/or internal body surfaces, with or without tissue loss. If this wound persists for more than 8 weeks, it is called a chronic wound, whereas wounds that develop in connection with certain diseases (venous or arterial vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus or decubital ulcer) are considered chronic from the time of their occurrence. An ulcer is a deep wound that extends at least into the dermis [1].

In Europe, venous leg ulcer (Ulcus cruris venosum) is the most common chronic wound. Secondary data analyses (analysis of health insurance data in Germany) have shown that between 810,000 and 1.1 million people in our neighbors suffer from a chronic wound each year. This corresponds to 0.9-1.2% of the population and is in line with figures from other Central European countries [2]. Venous ulcers account for approximately 60% of all chronic wounds. Venous ulcers are found more frequently in older populations [3].

Etiology

Venous ulcers develop on the basis of chronic venous insufficiency. The function of veins is to transport oxygen-depleted blood loaded with products of cellular metabolism from the periphery to the central organs of the heart and lungs. While the arteries can use the pressure pump of the heart to perform their task, this pressure has been exhausted in the venous portion of the circulation, after passing through the arterio-venous capillary territory. With the body in a horizontal position, the pressure gradient from the postcapillary region to the heart is just sufficient to ensure reverse flow. The flow pressure is then 15-25 mmHg in the venules, 8-20 mmHg in the V. femoralis communis, and 5-7 mmHg still in the right atrium. However, this “low pressure system” contains 85% of the total blood volume. In 24 hours, about 800 liters of blood must be drained per leg.

In sitting and standing, there is a pressure load due to the resulting hydrostatic pressure of about 80-90 mmHg as well as a displacement of 300-350 ml of blood from the thoracic cavity to the periphery and thus a dilatation of the venous capacity vessels. Several mechanisms are required to maintain venous return in this situation and lower the pressure back to 10-20 mmHg.

Respiration acts like a pressure-suction pump by opposing intrathoracic and intraabdominal pressure fluctuations.

Cardiac action accelerates venous blood flow, on the one hand, by draining blood from the right atrium and vessels near the heart into the right ventricle and, on the other hand, by shifting the valve planes during the expulsion phase.

The muscle pumps, especially the combined calf muscle and ankle pump, have an essential role. In the soleus muscle, pressure increases from about 13 to about 85 mmHg during contraction. This squeezes the muscle veins (the gastrocnemius muscle reaches a pressure increase from 11 to 23 mmHg and the quadriceps femoris muscle from 0 to 15 mmHg). Loss of this muscle/joint pump due to limited mobility results in arthritic congestion syndrome.

The venous valves are designed to prevent the backflow of blood to the periphery. They usually consist of two, sometimes three, sails with a convex edge projecting into the vessel lumen [4].

Consequences of a malfunction

A malfunction in a draining system leads to an increase in the volume of fluid (in this case, blood) to be disposed of. The term venous insufficiency summarizes conditions with impeded venous return of various etiologies. According to the localization of the cause, a distinction is made between subfascial and suprafascial venous insufficiency, and according to the course of the disease between acute and chronic insufficiency.

The venous ulcer develops in the course of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), which in turn, however, may well have arisen as a result of an acute event (deep vein thrombosis). In the subfascial region, CVI develops either as a result of thrombosis or deep conduction vein insufficiency, a varicose degeneration of the deep veins. The consequences of deep vein thrombosis are determined by the location of the thrombosis. Whereas isolated iliac vein thrombosis virtually never leads to ulcers if the distal veins are intact, thrombosis of the popliteal vein or the deep veins of the lower leg leads to visible consequences relatively quickly.

In the suprafascial portion of the venous system, dilatation of the veins known as varicosis with loss of valvular function can lead to CVI. Here, isolated dilation of the large truncal veins (V. saph. magna and V. saph. parva) has less dramatic consequences than varicose degeneration of single or multiple perforating veins.

A classification of CVI still in common use is that introduced by Widmer [5] in 1981 and named after him:

- Stage I describes the appearance of ankle edema with increased filling of small veins in the ankle area (corona phlebectatica paraplantaris).

- In stage II, the edema expands and skin changes occur. Hyperpigmentation (purpura jaune d’ocre), stasis dermatitis and sclerosis of cutis and subcutis (dermatoliposclerosis). Macular hypopigmentation is called atrophie blanche (Fig. 1). The decapillarized areas, which appear as white skin areas, are surrounded by dilated giant capillaries visible as reddish dots.

- Stage III is assigned to patients who have or have had a florid ulcer, designated a or b according to Marshall [6].

The CEAP scheme [7] describes in detail the

- Clinicalsigns in stages 1-6 (where 6 denotes the florid ulcer).

- Etiologicalclassification (primary, secondary)

- Anatomicdistribution (superficial, deep, perforators, not known)

- Pathophysiologicaldysfunction (reflux, obstruction, reflux and obstruction, not known)

The exact cause of the transition from CVI, which is by no means inevitable in all patients and can also be understood as a consequence of the only limited or eliminated pressure drop in the venous system during walking (ambulatory venous hypertension), to venous leg ulcers has not been conclusively clarified. Proteolytic enzymes and inflammatory mediators play a role. Ulcers can occur spontaneously or as a result of minor trauma.

Diagnosis

Successful treatment of venous ulcer requires correct diagnosis. The general history should include previous illness, surgery, occupation, family disposition, known allergies (contact sensitizations), current medications, and special exposures.

Specific questions must be asked about thrombotic events, previous ulcers, possible trauma involving the legs, onset of skin changes, and the first time the skin defect is noticed. The intensity of pain is best demonstrated by the patient using an 11-digit scale (from 0-10, visual analogue scale, VAS).

During inspection, attention is paid to visible varices, edema, joint changes, circumferential difference of the legs, localization of the ulcer, condition of the surrounding skin, condition of the wound edges. The condition of the wound surface and the amount of exudate (+, ++, +++) should be recorded. Palpation is used to assess pulse status, edematous swelling, dermatosclerotic changes, and pain points. Stemmer’s sign describes the inability to lift a fold of skin from the back of the second toe with two fingers and is seminal in the diagnosis of lymphedema. The instrumental diagnostics include

- directional (cw) Doppler ultrasonography of the arteries with determination of the Ankle Brachial Index (ABI),

- directional (cw) Doppler sonography of the veins with reflux diagnostics,

- a functional examination procedure such as light reflection rheography (LRR) or digital photoplethysmography (DPPG), and

- imaging procedures such as B-scan (possibly compression) sonography, color-coded duplex sonography and, only in rare justified exceptional cases, phlebography.

Specialized centers are reserved for 20 MHZ ultrasonography of the skin, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, laser Doppler, capillary microscopy, and measurement of transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen.

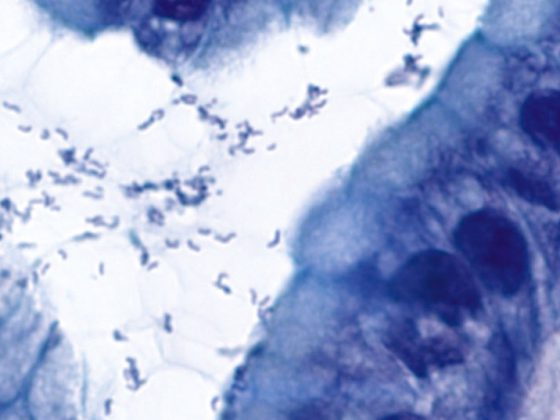

Laboratory diagnostics make do with a modest range: differentiated blood count, ESR and CRP as inflammation parameters, and blood sugar, uric acid, and cholesterol as metabolic parameters are routine. If contact sensitization is suspected, allergy diagnostics may be useful. Coagulation diagnostics should be performed if consequences for the patient or his relatives are to be expected. Ulcers that are resistant to therapy must be clarified histologically, if only to detect any underlying malignant causes. Wound swabs are of limited value but should always be performed.

In the wound documentation, the greatest length and greatest width of the wound are measured. The outlines of the ulcers can be traced with the help of foils. On some slides, a size indication can be obtained by counting boxes. Suitable documentation programs allow the planimetric evaluation of the foils. A digital camera should be used to take a photo of the wound with the centimeter measurement next to it. Digital photos integrate well with practice or clinic software. The rulers should include the patient code, date of admission, and body side. Legal aspects are becoming increasingly important. Photo documentation requires the written consent of the persons concerned at least if there is a possibility of public use of the photos for training purposes. Photo captions should not include names or reanonymizable information such as dates of birth.

Causal therapy must be aimed at eliminating the congestion in the venous system and preventing its recurrence. Compression therapy is the most important and effective measure in the fight against venous ulcer. It increases the flow velocity in the capillaries, reduces the diameter of the large veins, leads to the reabsorption of connective tissue fluid into the vessels and prevents renewed edema formation through effects on the vessel walls. Effects on the local inflammatory response, such as a decrease in the cytokines involved, may be involved in pain relief and healing. Impressive healing rates can be found after only 12 weeks of adequate compression alone.

Doppler sonographic control of the arterial supply should always precede the application of consistent compression therapy. Arterial pressures of 60-80 mmHg (corresponding to an ankle-brachial index of 0.5 in most cases) just allow compression, under observation, although it must be explicitly pointed out that such pressures already correspond to critical ischemia and compression therapy considered absolutely necessary here requires careful monitoring. Similarly, a cardiac cause of edema must be ruled out before starting compression to avoid a life-threatening volume shift. In the case of acute inflammations (e.g. erysipelas), compression must be avoided.

There are various systems for compression therapy in florid ulcers on the market. These range from the simple two-layer “Pütter” short-stretch bandages to multilayer dressings, ulcer stockings and adaptive bandages. The double-layer bandage with short-stretch bandages is the most widely used bandage in the treatment of venous leg ulcers in German-speaking countries. Its effectiveness and tolerability are based on the fact that it exerts hardly any pressure on the venous system at rest, but optimal pressure during movement (low resting pressure, high working pressure). The short-stretch bandages must be padded underneath.

Especially in the Anglo-Saxon countries, multi-layer bandages (combinations of e.g. absorbent cotton, short and/or long-stretch bandages) are used successfully. But also in Central Europe, several, mostly two-layer, systems have come onto the market in recent years. They offer increased comfort for both patient and practitioner with guaranteed compression pressures for several days.

Adaptive bandages can be individually adjusted to the patient. In addition, they can be used to respond well to a reduction in edema due to tighter wrapping. They are also suitable for self-investment. Single- or double-layer stockings for ulcer therapy have been successfully introduced They represent a hygienic, significant relief of patients’ lives. Intermittent appliance-based compression therapy is intended to accelerate the healing of florid ulcers. Multi-chamber systems are said to be superior to single-chamber systems in this respect.

Especially to prevent recurrences, round-knit compression stockings are prescribed after venous ulcers have healed. As a rule, compression class II stockings are used here (23-32 mmHg pressure in the ankle area). If the edema is more severe, compression class III (34-46 mmHg) may also be indicated. Manual lymphatic drainage and physiotherapy are highly effective ways of decongestion and complement compression therapy.

Surgical therapy

The purpose of surgical interventions in ulcer therapy may be to eliminate venous reflux, decrease intracompartmental pressures, or remove the ulcer. The purpose of surgical therapy measures:

- the elimination of insufficient epi- and transfascial vein sections

- the local ulcer therapy (shave therapy)

- Procedures involving the fascia cruris (fasciotomy, fasciectomy)

Endovenous procedures such as laser therapy, radiofrequency therapy, and foam sclerotherapy are good alternatives [8].

Vacuum therapy has proven particularly useful in the clinic and here especially in conjunction with subsequent mesh grafting. In Germany , it will also be reimbursed by payers in the outpatient sector from 2019.

Summary

Venous leg ulcer develops on the basis of chronic venous insufficiency, which in turn may have causes in both the deep and superficial venous systems or in the system of perforators. According to the cause, the most important therapeutic principle is stringent compression. Surgical measures should be incorporated into therapy wherever possible to achieve accelerated healing and prevent the occurrence of recurrences. Additional physical therapy procedures have proven effective.

Take-Home Messages

- Chronic wounds occur in the context of underlying diseases.

- Venous ulcers develop at the bottom of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI).

- Since compression therapy directly combats the consequences of CVI (congestion, edema), it is the most important component of successful therapy.

- The local therapy of the wound is based on current requirements such as exudate quantity, pain level or wound edge damage.

Literature:

- Dissemond J, Bültemann A, Gerber V, et al: Clarifying terms for wound care: recommendations of the Initiative Chronische Wunden (ICW)e.V. Dermatologist 2018; 69: 708-782.

- PMV Research Group University of Cologne. Epidemiology and care of patients with chronic wounds. An analysis based on the sample of insured persons AOK Hessen/KV Hessen 4/2016.

- Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, Bromen K, et al: Bonn Vein Study of the German Society of Phlebology 2003.

- Kügler C: Venous diseases. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH 2011; 11-21.

- Widmer LK, Kamber V, da Silva A, Madar G. [Overview: varicosis (author’s transl)]. Langenbeck’s Arch Chir 1978 Nov; 347: 203-207.

- Marshall M. Practical phlebology, in Ludwig M. (ed.) Gefäßmedizin in Klinik und Praxis, 3rd edition 2010; 82-87, Thieme Verlag. .

- Ludwig M, Rieger J, Ruppert V: Gefäßmedizin in Klinik und Praxis, Georg Thieme Verlag, 2nd edition 2010; 284.

- Carmel JE, Bryant RA: Venous Ulcers in Acute and Chronic Wounds. Elsevier 2016; 204-225.

- Medical compression therapy of the extremities with medical compression stocking (MKS), phlebological compression bandage (PKV) and medical adaptive compression systems (MAK), AWMF Register No. 037-005, valid until December 31, 2023, German Society of Phlebology.

- Stoffels I: Systematics of surgical therapies in Dissemond J, Kröger K. Chronic wounds. Elsevier Ltd 2019.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(3): 9-12