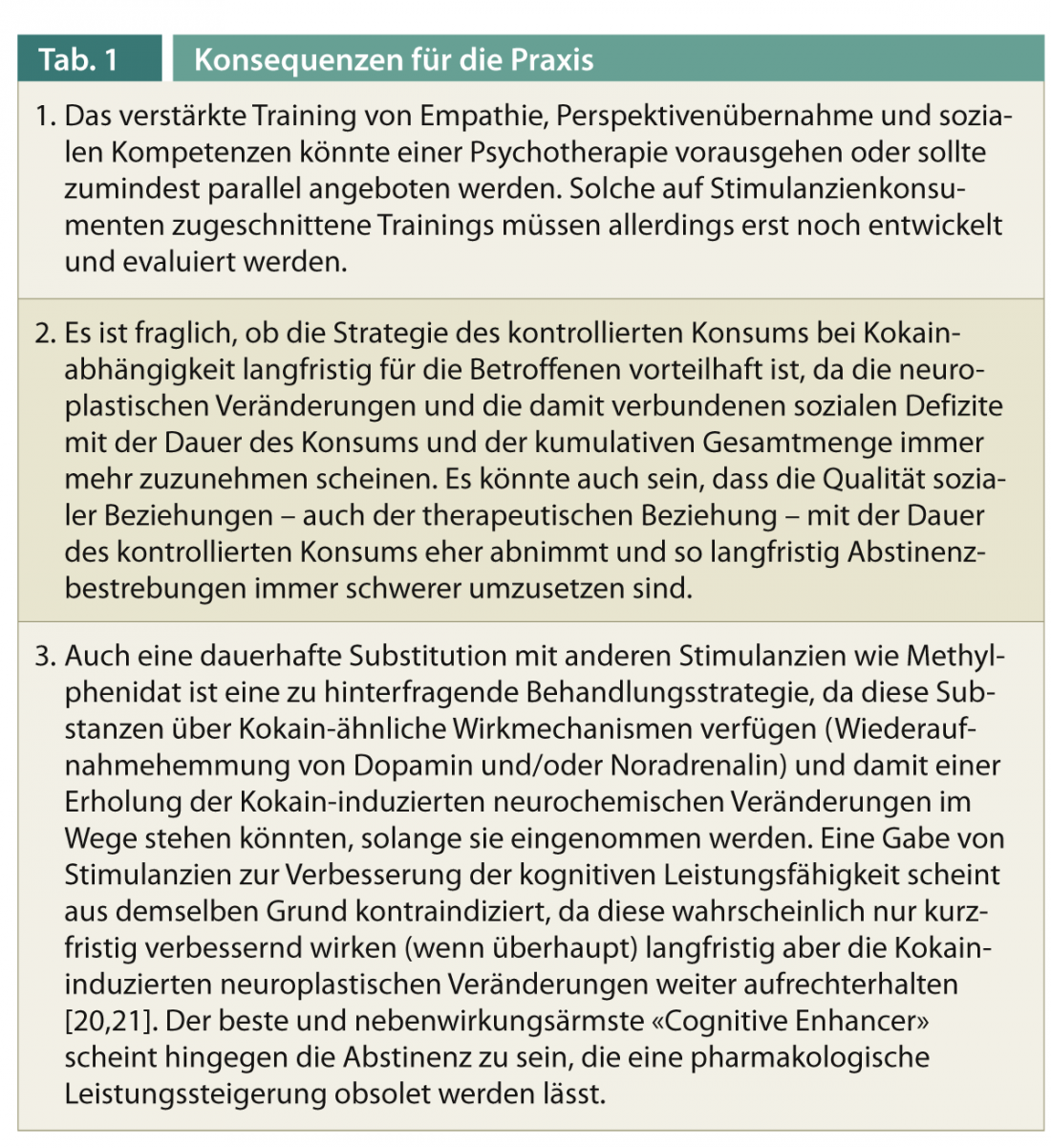

Cocaine users show specific impairments in social-cognitive skills that are linked to their social functioning in everyday life. They exhibit less social contact and deficits in empathy, while heavier use adds problems in perspective taking. Cocaine users also behave somewhat less prosocially on average. Like the impairments in attention and memory, the empathy deficit appears to be at least partially substance-induced. It is likely that these disturbances in social perception and behavior may also make a therapeutic relationship with these individuals difficult, which may help explain the high relapse rate among severely cocaine-dependent individuals, even after intensive therapy. Since social-cognitive impairments seem to be partially reversible after abstinence, these findings could be implemented in therapy practice in several ways (Table 1).

Many therapeutic psychologists and psychiatrists observe that chronic or dependent cocaine users change in personality over the course of their use careers. Clinically and phenomenologically, it is noticeable that some patients become increasingly emotionally flat and egocentric [1, 2]. Cocaine users also show up to a 22-fold increased risk of comorbid antisocial personality disorder [3].

Previously, it was thought that a personality disorder characterized primarily by the violation of social norms was more likely to condition consumption; however, whether chronic consumption may also promote antisocial behavior has not previously been studied. Finally, in numerous imaging studies, chronic cocaine users show alterations specifically in those brain regions that we now know are of great importance for social skills and preserved social interaction ability [4–8]. These mainly include the medioprefrontal (MPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the anterior cingulate (ACC), temporal cortical areas such as the insula, and the temporal pole region, where either gray matter thickness or glucose metabolism was decreased. However, to date, systematic and experimental studies have been lacking to objectively characterize and quantify the social-cognitive impairments of cocaine users. This is despite the fact that we have recently learned how important these social skills can be for the development, course, and treatment of psychiatric disorders, as has been demonstrated many times using the example of schizophrenia [9].

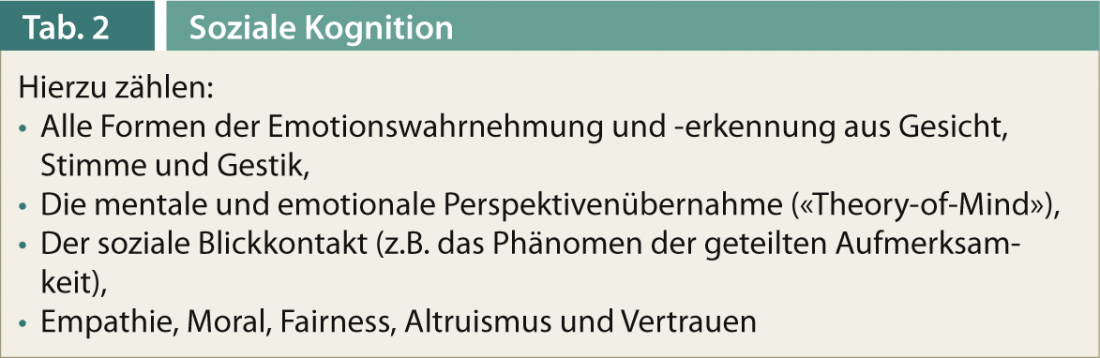

It has also been suggested that social cognition may have a strong influence on the development and progression of stimulant addictions as well as their treatment [10, 11]. Whereas social cognition is a somewhat unfortunate collective term used to summarize various cognitive functions that enable an individual’s ability to interact socially (Table 2). Thus, impairments in social-cognitive functioning are thought to promote social isolation, aggressiveness, and depression proneness, which contributes to the maintenance of dependent use [10]. It has also been postulated that addiction affects brain functions that are relevant to social functioning (see above). Substance use leads to a reduction in the importance of social sources of reinforcement and thus to social withdrawal, while the importance of consumption as the main source of reward is increasingly important [11, 12]. The importance of social relationships to treatment success is reflected in the recent finding that greater social support was also associated with significantly longer duration of abstinence among alcohol-dependent individuals [13].

The Zurich Cocaine Cognition Study

In order to broadly investigate social cognition and interaction in dependent and non-dependent cocaine users for the first time, we developed and conducted the Zurich Cocaine Cognition Study (ZuCo2St), funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (http://p3.snf.ch/Project-123516). This longitudinal study was designed not only to characterize the various facets of social cognitive skills and social behavior under experimental conditions, but also to provide clues as to whether changes in this domain are more predisposed or may also be a consequence of cocaine use. We focused not only on dependent users, but we also studied regular but (still) non-dependent users, who represent the largest group of cocaine users. In addition, we focused on comparatively pure cocaine users, as we were able to exclude any form of polysubstance use on the basis of toxicological hair analyses.

A total of 250 cross-sectional subjects (145 cocaine users, 105 healthy controls) were studied, of whom approximately 100 users and 70 control subjects made comparable for age, education, smoking, and sex were included in the final analyses. 46 users had to be excluded because of polytoxicomania, lack of cocaine use, or psychiatric comorbidities. Longitudinally, we examined a total of 132 individuals a second time over the one-year course, but of these, only about 105 participants were suitable for longitudinal analysis because some users had meanwhile switched substances (most frequently from cocaine to MDMA) or met other exclusion criteria (e.g., intervening stroke, medication with psychotropic drugs, etc.).

Cognition, color vision and early information processing

First, we were able to confirm in the cross-sectional study that dependent cocaine users exhibit broad cognitive deficits that already exist in somewhat milder form in regular but non-dependent users [14]. In dependent users, changes in working memory were most pronounced, whereas in non-dependent individuals, concentration and attention were most likely to be affected. Overall, 12% of nondependent and 30% of dependent users showed clinically significant and daily-relevant cognitive impairment (>2 standard deviations), with a particularly sharp increase in risk for cognitive decline beyond 500 g of lifetime cocaine use. These findings could not be explained solely by clustered symptoms of the often comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or depression. Test performance also correlated strongly with consumption parameters, i.e., the more consumed, the greater the impairments. It was also shown that the age at which consumption begins plays a major role in the development of intellectual performance deficits, as individuals who began using before the age of 18, and thus before brain maturation was complete, revealed the most severe deficits [14].

We were also able to show that occasional as well as dependent users exhibit alterations in color perception and early information processing, suggesting a change in neurochemistry (dopamine and/or norepinephrine systems) that already begins with occasional use. Thus, 40-50% of cocaine users showed clinically relevant color vision deficits, mostly in the form of an otherwise rather rare blue/yellow deficiency, explained by disturbances of the retinal dopamine balance. The occurrence of blue/yellow color vision impairment was also associated with more severe cognitive losses [15]. The electrophysiologically measured changes in early attentional filtering were also strongly associated with cocaine craving, suggesting neurochemical changes resulting from cocaine use. These abnormalities were also already found among non-dependent, regular users [16].

In the initial analysis of longitudinal data, we focused on the one-year trajectory of cognitive performance among individuals who either greatly reduced (mean -72%) or terminated or greatly increased (mean +297%) their use. Cocaine concentration in a 6-cm hair sample was used as an objective measure of cocaine use over the previous six months. The data show that large reductions in consumption within a year lead to improved cognitive performance, especially in working memory, but also in attention and long-term memory. Individuals who stopped using cocaine altogether even reached the performance level of the control group, while individuals who massively increased their use showed a further significant decline in cognitive performance [17]. This suggests that the cocaine-associated cognitive deficits may be partly substance-induced. The reversibility of some deficits also indicates that neuroplastic and adaptive processes are involved, which can probably also be influenced psychotherapeutically or pharmacologically.

Social cognition and interaction

In our research on social skills, we focused on two main aspects: social cognition, i.e., recognizing, understanding, and feeling other people’s emotions and intentions, and social interaction, where we focused on fairness preferences and prosocial behavior. To measure emotion perception and recognition, we presented emotional facial expressions, complex emotional visual scenes, or emotionally colored speech presentations in various tasks. Here, cocaine users were fully capable of correctly recognizing and naming emotions in visual material (faces, pairs of eyes, complex image content) [12]. However, they showed problems in recognizing the correct emotion from speech melody (prosody) as well as in detecting emotionally mismatched visual and speech material [18]. The latter indicates a deteriorated integration of different channels of emotion perception. To measure empathy ability, we employed complex emotional imagery. Here, it was found that both dependent and non-dependent consumers reported being less emotionally resonant when confronted with emotional image content [12].

Through in-depth social network interviews, we also found that cocaine users have fewer social contacts overall and that such contacts were judged to be more emotionally stressful. Cocaine users also had a history of committing more crimes. Interestingly, the ability to empathize was correlated with the size of the social network as well as with the number of crimes, such that less empathic individuals also had fewer social contacts and were at higher risk for criminal behavior [12].

Using video-based stimulus material in which a complex everyday event was depicted (a meal between two prospective couples), we were able to examine realistically the understanding of other people’s emotions and intentions. This mental and emotional perspective-taking (“theory-of-mind”) is important in order to be able to move appropriately in the social environment. In fact, only the dependent consumers showed slight deficits here, often recognizing the correct intention or emotion but placing excessive importance on the actions or emotions, thereby exaggerating perspective taking. This could indicate a cognitive compensation mechanism and also supports our hypothesis that the integration of complex emotional information in particular is more difficult in chronic cocaine users. Perspective taking as well as social network were correlated with cocaine use, i.e., the more used, the poorer the understanding of others’ actions and the fewer social contacts were present [12].

To test social interaction skills, we additionally applied interaction tasks borrowed from economic game theory, in which participants were asked to divide amounts of money between themselves and a fellow player. Here we saw that cocaine users acted less altruistically and even when the total amount of money available became smaller, they increased their own profit to the disadvantage of the other player. Thus, consumers behaved in a more self-centered manner and this behavior was not correlated with consumption parameters, which may indicate that this is more of a predisposing personality trait [19].

Preliminary analyses of longitudinal data now suggest that empathic ability may also covary with increasing or decreasing cocaine use. Again, empathy improved among users who greatly reduced or stopped use, while individuals who greatly increased it showed worsening emotional empathy. Thus, social functions can be affected by substance-induced neuroplastic adaptation processes, but apparently also improve after prolonged abstinence.

Deficits not linked to dependence

It should be emphasized again at the end that cognitive and social deficits only develop after intensive use, but are not linked to dependence. We also saw in our sample that one third of the users were able to reduce or completely stop consumption (13%), partly without any therapeutic measures, the majority of the users did not show any major changes in consumption (39%), while a not inconsiderable proportion increased consumption very strongly (27%) or changed substance (14%) within a year. We are now conducting further analyses to try to determine whether risk or resilience factors for increased consumption can be gleaned from our extensive data.

Prof. Dr. Boris B. Quednow

Literature:

- Spotts JV, Shontz FC: Int J Addict 1982; 17: 945-976.

- Spotts JV, Shontz FC: Int J Addict 1984; 19: 119-151.

- Rounsaville BJ: Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56: 803-809.

- Bolla K, et al: J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16: 456-464.

- Ersche KD, et al: Brain 2011; 134: 2013-2024.

- Franklin TR, et al: Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51: 134-142.

- Makris N, et al: Neuron 2008; 60: 174-188.

- Volkow ND, et al: Synapse 1992; 11: 184-190.

- Couture SM, et al: Schizophr Bull 2006; 32: 44-63.

- Homer BD, et al: Psychol Bull 2008; 134: 301-310.

- Volkow ND, et al: Neuron 2011; 69: 599-602.

- Preller KH, et al: Addict Biol 2013a; In press.

- Mutschler J, et al: Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2013; 39: 44-49.

- Vonmoos M, et al: Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 35-43.

- Hulka LM, et al: Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013a; 16: 535-547.

- Preller KH, et al: Biol Psychiatry 2013b; 73: 225-234.

- Vonmoos M, et al: Cognitive impairment in cocaine users is drug-induced but partially reversible: evidence from a longitudinal study. 2013b; Submitted.

- Hulka LM, et al: Cocaine users manifest impaired prosodic and cross-modal emotion processing. Front Psychiatry 2013b September 5th; doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00098.

- Hulka LM, et al: Psychol Med 2013c; In press.

- Quednow BB: BioSocieties 2010a; 5: 153-156.

- Quednow BB: AddictionMagazine 2010b; 36: 19-26.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry No. 5/2013