Diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever and weight loss – non-specific symptoms that together are typical of Crohn’s disease. But watch out: Intestinal tuberculosis can also be hidden behind the appearance. Accurate diagnosis is crucial, as the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy for suspected Crohn’s disease promotes the progression of tuberculosis.

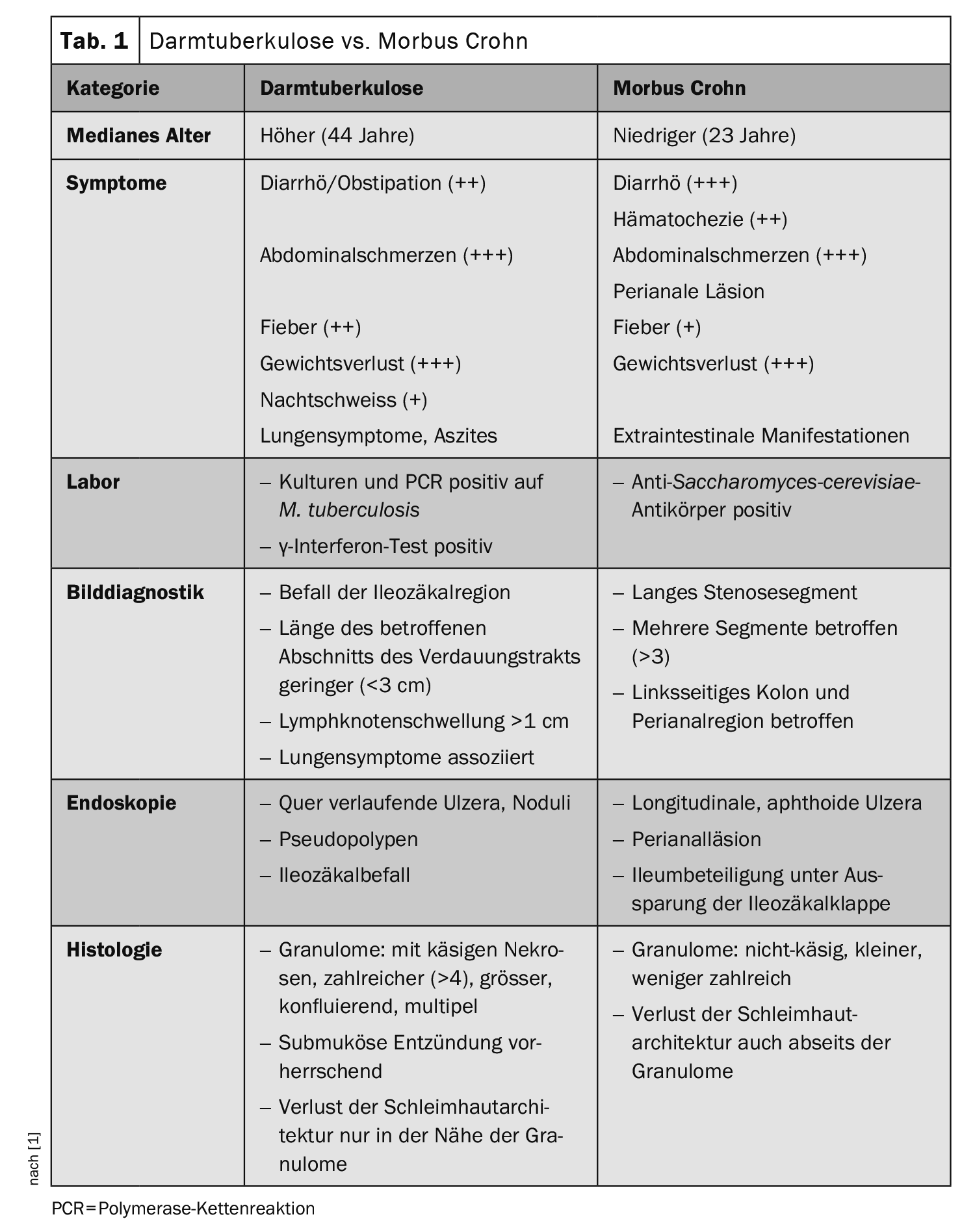

In Switzerland, around 550 people are affected by tuberculosis (TB) every year. The incidence is 6.5 cases per 100,000 people, 77% of those affected come from abroad. The majority of cases affect the lungs (approx. 70%), but in principle any organ can be affected. Intestinal TB is particularly difficult to diagnose, as the symptoms suggest confusion with Crohn’s disease ( Table 1).

To illustrate this, Thomas Calixte, Internal Medicine at the CHUV in Lausanne, and colleagues report on a 48-year-old patient of Turkish origin who had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease for 2 months [1]. Previously, the man had experienced diarrhea with asthenia, weight loss of 15 kg and night sweats over a period of one year. An ileocolonoscopy showed two ulcers with erythematous borders of the mucosa of the terminal ileum and an ulcer in the caecum with slightly erythematous mucosa.

Corticosteroid therapy was initiated, followed by additional treatment with azathioprine (after a negative γ-interferon test). Cough and worsening B-symptoms finally led to a chest CT, which revealed several caverns in the left upper lobe. A PCR test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the sputum was positive and confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. As the digestive symptoms with diarrhea did not change, intestinal tuberculosis was considered and confirmed by PCR testing for M. tuberculosis in the previously taken ileocecal biopsies.

The immunosuppressive treatment was then discontinued, after which the pulmonary and intestinal symptoms gradually improved in the course of quadruple anti-tuberculosis therapy.

Ileocecal region is most frequently affected

Intestinal tuberculosis is usually caused by the ingestion of sputum contaminated with M. tuberculosis in the presence of pulmonary tuberculosis, the authors write. Less frequently, infestation occurs via the hematogenous or lymphatic route or through contact infection. The ileocecal region is most frequently affected, accounting for 65% of cases. Respiratory symptoms such as coughing, bloody sputum or dyspnea can occur in advanced forms due to the lung infestation.

According to the recommendations of the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO), a diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis can be made if one of four criteria is met:

- Tissue cultures positive for M. tuberculosis (colon biopsy, lymph nodes)

- Positive PCR test for M. tuberculosis

- Histological detection of typical acid- and alcohol-resistant rods (should be confirmed by PCR test for M. tuberculosis )

- Histological evidence of caseous granulomas (should be confirmed by PCR test for M. tuberculosis ).

Diagnostics using PCR test

According to the authors, the routine laboratory tests are unspecific. The γ-interferon test, which is mainly used as a screening before the initiation of immunosuppression, can provide an indication of the diagnosis if the result is positive, but does not in itself indicate active tuberculosis. Radiologically, infestation of the ileocecal region, a short length of the affected section of the digestive tract (<3 cm) und das Vorhandensein von Lymphknotenschwellungen>1 cm can indicate a diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis.

Endoscopic examination can also reveal few specific features, but has the advantage that biopsies can be taken for histopathological examination. In histopathology, intestinal tuberculosis can be diagnosed according to the WGO by the detection of acid and alcohol-fast rods or a cheesy granuloma (preferably in the ileocecal biopsy). However, the low sensitivity (68%) with the high risk of false-negative findings must be taken into account. The authors therefore refer to the possibility of increasing sensitivity by repeated sampling (at least 8-10 biopsies).

The sensitivity of cultural detection is also low (10-35%). A PCR test for M. tuberculosis complex promises greater success in cases of suspected TB. The sensitivity of PCR on ileum biopsies is up to 65%, the specificity is very high at 93-100%. A negative PCR test therefore does not rule out intestinal tuberculosis. Microscopically, the detection of acid- and alcohol-resistant rods offers a rapid and very specific test (100%), although with low sensitivity (17.3-31%) depending on the study. The WHO recommends a PCR test for M. tuberculosis complex if tuberculosis is suspected.

Medication responds well

If intestinal tuberculosis is not treated or treated inadequately, complications such as intestinal obstruction (24%) can result, associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Perforations, stenoses, intestinal fistulas and bleeding in the digestive tract are also described.

The response to standard drug treatment (2 months of quadruple therapy with rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide, followed by 4 months of dual therapy with rifampicin and isoniazid) is considered to be very good. The risk of non-indicated surgical intervention can therefore be reduced by correct diagnosis, Calixte and colleagues write. Monitoring antituberculosis drug concentrations may be useful to limit the risk of over- or underdosing in view of the possibility of malabsorption due to intestinal inflammation.

Literature:

- Calixte T, Konascha A, von Garnier C, et al: Intestinal tuberculosis: The great imitator. Swiss Medical Forum 2023; 23(44): 1404-1407; doi: 10.4414/smf.2023.1265460377.

GASTROENTEROLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 2(1): 19-20

Cover picture: This photomicrograph reveals Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria using acid-fast Ziehl-Neelsen stainMagnified 1000 X. The acid-fast stains depend on the ability of mycobacteria to retain dye when treated with mineral acid or an acid-alcohol solution such as the Ziehl-Neelsen, or the Kinyoun stains that are carbolfuchsin methods specific for M. tuberculosis.

Author: CDC/Dr. George P. Kubica (wikimedia)