The treatment of allergic diseases, regardless of the triggering source resp. of the agent, is based on three principles: avoidance, symptomatic treatment, and allergen-specific treatments such as specific immunotherapy. Most commonly, symptomatic/medicinal therapy is used due to exposure prophylaxis, which can be difficult to achieve, and in ignorance of allergen-specific treatment. Nowadays, we have various effective substance groups at our disposal, which, used individually or in combination, often lead to a good therapeutic result.

To trigger allergic, IgE-mediated symptoms, sensitization to the triggering substance is required, i.e. there must have been contact with the causal allergen at least once before the reaction. In general, the therapeutic options for allergic diseases – regardless of the allergen – are based on three principles:

- Avoidance of the allergen (whenever possible)

- Drug treatment (for symptoms)

- specific therapy.

Avoiding a trigger is not always an easy task. For example, it is easier to prescribe an alternative to a penicillin antibiotic for an infection treatment than to avoid a wasp sting.

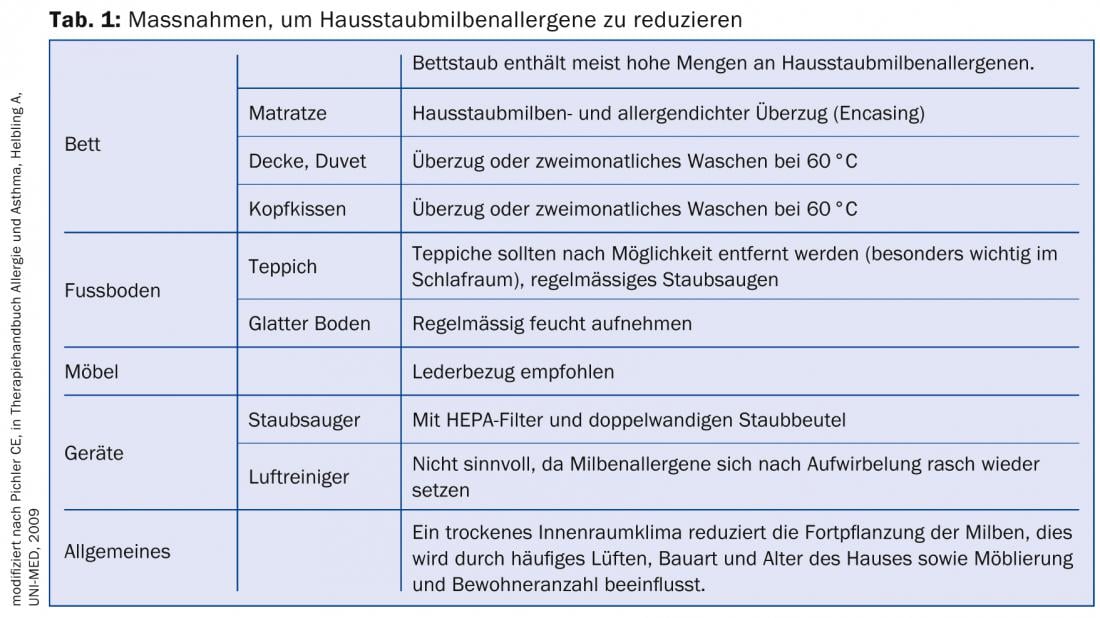

In the case of perennial allergen exposure – usually residential or indoor allergy – avoiding a source is often particularly difficult. Exposure to house dust mite allergens is usually not acutely perceived, as latent inflammation manifests itself at the beginning only under certain circumstances, such as during sports activities with respiratory distress. Once a house dust mite allergy has been diagnosed, the concentration of mite allergens can be reduced by consistent sanitation measures so that the living conditions for the mites are made more difficult (Tab. 1).

Although often discredited, dust mite allergen-proof encasings are useful measures because the encasings tested can significantly reduce allergen levels [1]. However, the costs are currently not covered by health insurance.

The procedure for a diagnosed pet allergy is more problematic because both cats and dogs are considered “family members.” In these situations, it is urgent that the animals at least no longer have access to the bedroom. Basically, the same remedial measures apply as for dust mite or mold allergy, i.e. regular cleaning of living spaces, carpets and dust deposit areas. In principle, allergy sufferers are advised not to keep pets.

Mucosal and respiratory symptoms can often attenuate with regular to chronic allergen exposure. Although there is usually persistently obstructed nasal breathing or the eyes are always slightly reddened, the patient finds the complaints less disturbing than the pollen allergy sufferer, who reacts acutely from one hour to the next with sneezing, watery rhinitis or conjunctivitis [2].

Whereas in pollen allergy sufferers the symptoms are triggered by messenger substances released from mast cells, such as histamine or leukotrienes, in house dust mite allergy sufferers there is chronic mucosal inflammation maintained by lymphocytes and eosinophils. This explains why antihistamines are not always sufficiently effective despite obvious allergy, but only anti-inflammatory drugs such as topical corticosteroids (KS) lead to the goal. Sometimes the inflammatory process progresses, as in the case of some occupational allergies (e.g. isocyanates, platinum), so that even a change of location or occupation does not always lead to a reduction in symptoms.

Seasonal allergen contacts can hardly be avoided and are usually treated symptomatically or then specifically by means of immunotherapy. Pollen allergy can occur even where the triggering plant blooms miles away. Nevertheless, certain preventive measures can be taken in the case of aerogenically triggered allergies. For example, you can find out about the flowering phases of the allergy-relevant plant using pollen apps or on the Internet and preferably keep the windows closed at this time and limit outdoor stays to the bare minimum.

Drug treatment of respiratory allergies

Symptomatic is the most commonly used therapy, as it is usually rapid and well effective. Various preparations can be purchased as “over-the-counter” (OTC) products directly from the pharmacy. But often the treatment is to optimize, so a visit to the doctor is inevitable. The main problem with drug therapy success is the lack of knowledge about how and when to use the drugs so that freedom from symptoms results. It is important that if symptoms are present, therapy is administered consistently for two to three weeks regardless of climatic conditions. Several treatment options for allergic rhinitis or conjunctivitis are available on the market. Two classes of agents, namely antihistamines and topical KS are considered evidence-based therapy for both seasonal and perennial allergic diseases, both in children and adults [3].

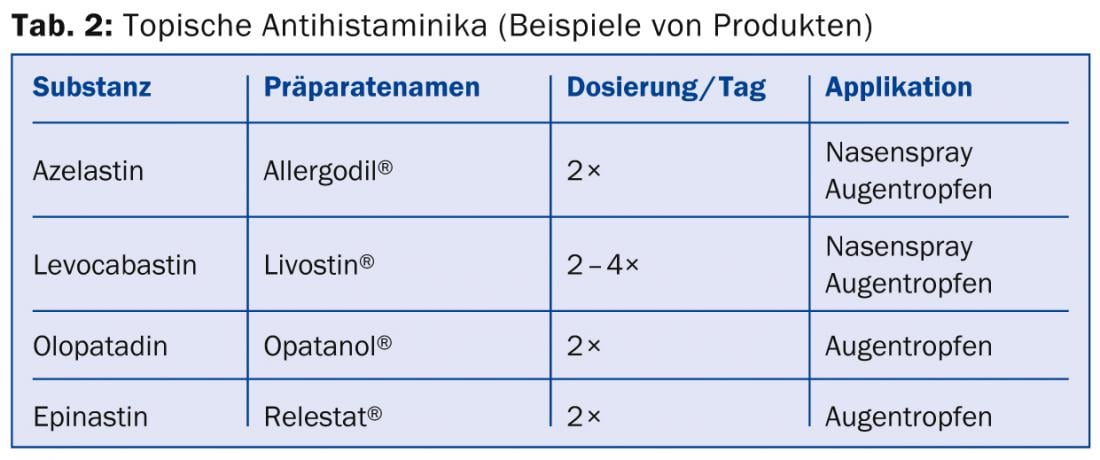

Antihistamines: Since histamine is considered the most important mediator substance for acute allergic symptoms, the use of antihistamines is understandable for most users. In cases of low distress, the use of topical antihistamines may be sufficient for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis or rhinitis (Tab. 2) . Lens wearers should observe the recommended time of 10 minutes between application of the drops and insertion of the lenses or refrain from using contact lenses during the symptomatic phase.

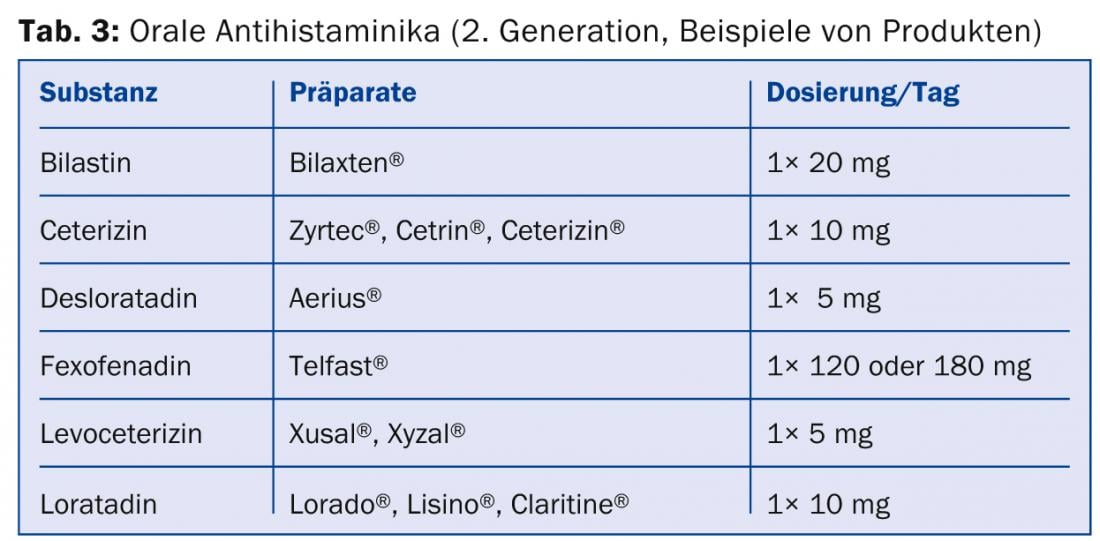

After oral administration, antihistamines take effect within 30-60 minutes. Since first-generation antihistamines are generally sedating and may have other unpleasant side effects such as dry mouth, second-generation antihistamines should be prescribed for the treatment of everyday allergic symptoms (Table 3) . Fexofenadine and bilastine in particular do not appear to cross the blood-brain barrier [4]. On the other hand, cetirizine, of which several OTC generics are available, virtually obligatorily causes fatigue when the dose is doubled. Therefore, especially drivers of cars or airplanes should be made aware of these potential side effects of antihistamines [5].

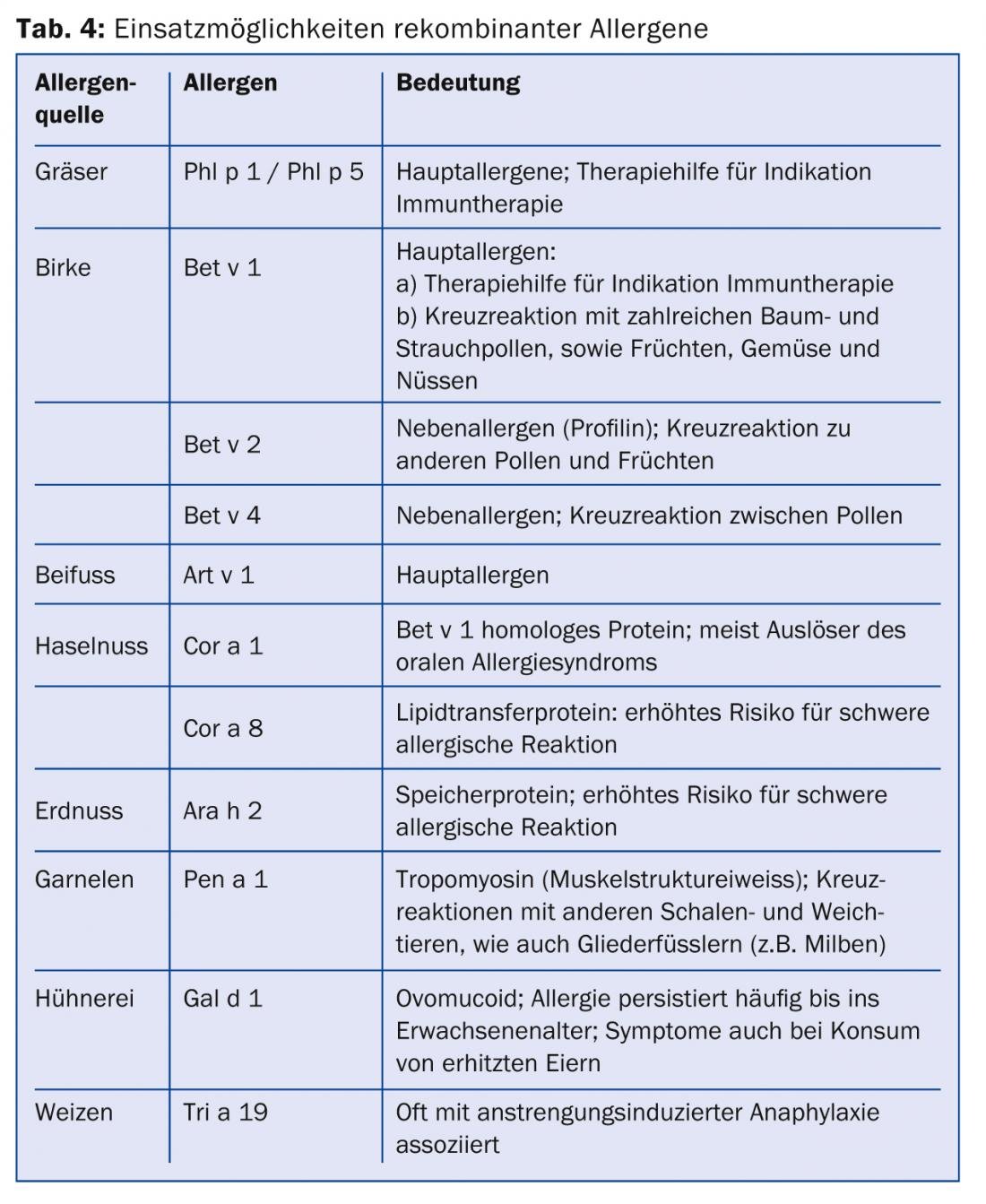

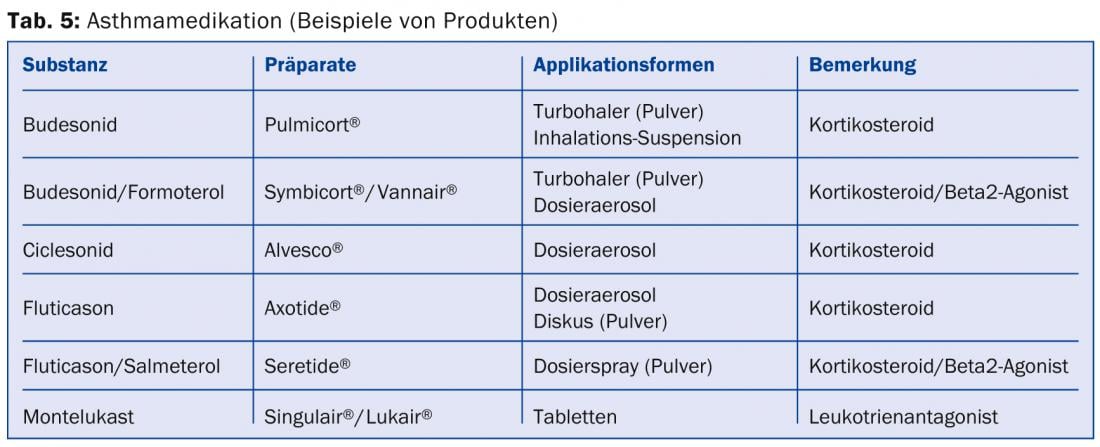

Topical corticosteroids: Allergic reactions result in inflammatory reactions triggered by T cells, eosinophils and basophils with release of various cytokines and mediators, which explains the efficacy of corticosteroids (Tables 4 and 5) .

They are indicated, for example, when there is a chronic inflammatory reaction with blocked nasal breathing. Some studies have shown that topical corticosteroids are more effective than oral antihistamines, especially in the presence of obstructive rhinopathy, which is why they are used as first-line therapy for intermittent allergic rhinitis in some countries [6]. The optimal therapy effect is achieved after three to five days. Topical corticosteroids can be used for several months.

The most common side effect of nasal application is dry mucous membrane with increased susceptibility to nosebleeds, which can be reduced by additional use of a greasing nasal ointment. With consistent use of topical nasal corticosteroids, a decrease in concomitant allergic conjunctivitis is also often observed.

Topical corticosteroids also form the basic therapy in asthma, in combination with a beta2-agonist depending on the severity of asthma [7]. Side effects may include hoarseness or, rarely, pharyngeal candidiasis, which can usually be prevented by consistent mouth rinsing after application or by using priming chambers (general recommendation for metered dose inhalers). If hoarseness occurs, switching to another preparation may also be beneficial. Although the side effects of topical corticosteroids are low compared with systemic corticosteroids, it is not yet clear whether long-term use with higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids carries an increased risk of osteoporosis [8].

Leukotriene receptor antagonists: Leukotriene antagonists are valuable drugs in allergic respiratory diseases, although their value is often questioned. They attenuate the inflammatory response and have an effect on tissue and blood eosinophilia. Montelukast has been shown to be effective in allergic rhinitis and asthma primarily as an add-on therapy [9, 10]. Thus, in combination with an antihistamine, a stronger effect is achieved for nasal symptoms than when using the individual preparations. In asthma, additional prescription of montelukast to baseline treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid may achieve a better effect than doubling the dose of the topical corticosteroid.

Systemic corticosteroids: In cases of massive symptoms and/or insufficient response despite extended therapy (e.g., antihistamines combined with montelukast and/or topical corticosteroids), short-term oral administration of prednisolone (5-10 mg/d for three to four days and for asthma 0.5 mg/kgKG for four to seven days), a reduction in symptoms can usually be achieved rapidly with the continuation of other therapy. It is important to note that prednisolone taken orally is not effective for several hours. We advise against intramuscular application (e.g. Kenacort®), among other things because of the side effects caused by the depot effect.

Mast cell stabilizers: Mast cell stabilizers such as Chromone or Nedocromil are used topically as eye drops or nasal sprays. Chromones are not absorbed and must be applied several times daily due to their short half-life. Side effects have been poorly reported, making these drugs popular for pediatric indications or pregnancy.

β2-Mimetics: A short-acting β2-mimetic is always indicated for the treatment of attacks in asthma. Therapy with a β2-agonist alone as continuous therapy for asthma is not indicated [11].

Anti-IgE (Omalizumab): Because pure allergic asthma, especially seasonal asthma, is usually not severe, omalizumab is rarely used. Omalizumab is also effective in seasonal or allergic rhinitis, but is not very useful because of its high cost. Treatment with the anti-IgE could be a treatment option in patients with IgE-mediated occupational allergy (e.g., farmer, baker), but the necessary studies are lacking.

Specific therapies

Preventive as well as combined therapeutic measures are often necessary to control allergic symptoms.

Specific immunotherapy (SIT): SIT is the only causal therapy available for inhalant allergies [12, 13]. The indication should be made by the allergist, the therapy can usually be performed by the family doctor.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT): SCIT is the classic form of SIT. Pre-seasonal SCIT can be distinguished from perennial SCIT. Whereas perennial SCIT, after up-dosing, progresses to a three-year maintenance phase with one-month injection intervals, preseasonal SCIT is usually performed once a week for four to eight weeks prior to the pollen season for three consecutive years. In pollen allergy, the efficacy after three years of treatment is about 80% with reduction of medication consumption by 50%. The level of suffering can be significantly reduced; in most cases, symptoms are only realized when the pollen load is high.

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT): SLIT preparations have been available in aqueous suspension in Switzerland for a few years and are increasingly used as an alternative to SCIT, including since the introduction of “grass tablets” (Grazax® and Oralair®). Based on the latest meta-analyses, SLIT with selected allergens can also be used successfully in children with allergic rhinitis and asthma [14]. An important advantage, apart from its effectiveness, is that SLIT has clearly fewer and much less severe side effects compared to SCIT. Patients should be trained in the management of allergic reactions despite the rarity of side effects. In addition, it is important to keep an eye on patients’ medication adherence.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The therapeutic options for allergic diseases are based on three principles:

- Avoidance of the allergen

- Drug treatment (for symptoms)

- specific therapy.

- Symptomatic is the most commonly used therapy. It is usually fast and well effective. Antihistamines, topical corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, systemic corticosteroids, mast cell stabilizers, β2-mimetics, anti-IgE (omalizumab) are available.

- Preventive and also combined therapeutic measures such as specific, subcutaneous or sublingual immunotherapies are often necessary to control allergic symptoms.

Prof. Arthur Helbling, MD

Literature:

- Halken S, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003 Jan; 111(1): 169-176.

- Herwig LM, et al: Practice 2004; 93: 267-273.

- Brozek JL, et al: Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines 2010 Sep; 126(3): 466-476.

- Hindmarch I, Shamsi Z, Kimber S: Clin Exp Allergy 2002; 32: 133-139.

- Jáuregui I, et al: J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013; 23(1): 27-34.

- Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, Puy RM: BMJ 1998; 317: 1624-1629.

- http://ginasthma.org

- Buehring B, et al: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132(5): 1019-1030.

- Rodrigo G, Yanez A: Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96: 779-786.

- Price DB, et al: Thorax 2003; 58: 211-216.

- Hasford J, Virchow JC: Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 900-902.

- Bousquet, Lockey Malling: J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 102: 55-62.

- Zuberbier T, et al: Allergy 2010 Dec; 65(12): 1525-1530.

- Radulovic S, et al: Allergy 2011; 66(6): 740-752.

- Dürr C, Helbling A: Therapeutische Umschau 2012; 69(4): 253-259.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(2): 17-23