Important developments in CF treatment and management strategies have led to improvements in the health status of people with this disease. It is widely recognized that survival is improving, at least in part due to early and aggressive treatment and therapeutic advances. However, the use of multiple medications and therapies can be complex, demanding, and time-consuming for both the patient and their family.

Important developments in CF treatment and management strategies have led to remarkable improvements in the health status of people with this disease. It is widely recognized that survival is improving [2], at least in part due to early and aggressive treatment and therapeutic advances [3]. However, the use of multiple medications and therapies can be complex, demanding, and time-consuming for both the patient and the patient’s family [4,5]. As a result, members of the multidisciplinary CF team often have long and sometimes intense relationships with patients and their families. The team must provide holistic and patient/family-centered care to help people with CF achieve a balance between optimal treatment and quality of life [6].

While both CF teams and patients readily embrace this philosophy of care, the reality is that complex treatment regimens place an ever-increasing burden on patients and their families. This can lead to poor adherence to therapy [7,4] and low competence in administering therapy, which can adversely affect health outcomes [4]. “Treatment adherence” is a preferred term to describe how patients’ health behaviors are consistent with the agreed-upon recommendations of CF team members [8]. Optimal treatment adherence is difficult to define, but it almost always means taking the right treatment in the right way at the right time. It is well known that treatment adherence varies depending on the complexity of the treatment regimen and how it is measured [9,3].

Consequences of suboptimal treatment adherence in CF.

Optimal treatment adherence is closely related to better treatment outcomes and lower risk of hospitalization [10–12]. Suboptimal treatment adherence has been shown to be the leading cause of treatment failure [13] and leads to poor health outcomes [14]. It is explicitly associated with treatment failure, lower quality of life, reduced baseline lung function, and higher morbidity, and is also predictive of the need for intravenous antibiotics [8,10–12,14,15]. For this reason, improving treatment adherence is one of the most important psychosocial challenges in CF care [16].

Factors associated with treatment adherence

There are many issues that can impact adherence to CF treatments and interventions. An overview is given in Table 1 [1], in which the possible factors are divided into the following core areas: Patient-Related Factors, Health System-Related Factors, Disease-Related Factors, Socioeconomic Factors, and Therapy-Related Factors.

For example, patient-related factors that affect treatment adherence are broad and include factors unique to each patient. It is known that the patient’s knowledge, skills, and abilities influence treatment adherence, including knowledge of treatment [17] and disease [18], ability to perform therapy [19], and educational level [20]. The patient’s personal attitude and organization also play a role in treatment adherence [21] and beliefs [22,23] just like the ability to manage time [18] and prioritize [24]. Patient mental health may also affect treatment adherence through depression and anxiety [25]. This also applies to factors related to the patient’s immediate environment, such as the role of family/caregivers and the social environment. Family/caregiver support and organization can help or hinder treatment adherence [26]. In addition, social life and social pressures [21,27,28] and the availability of non-family support systems [29] may also contribute to treatment adherence.

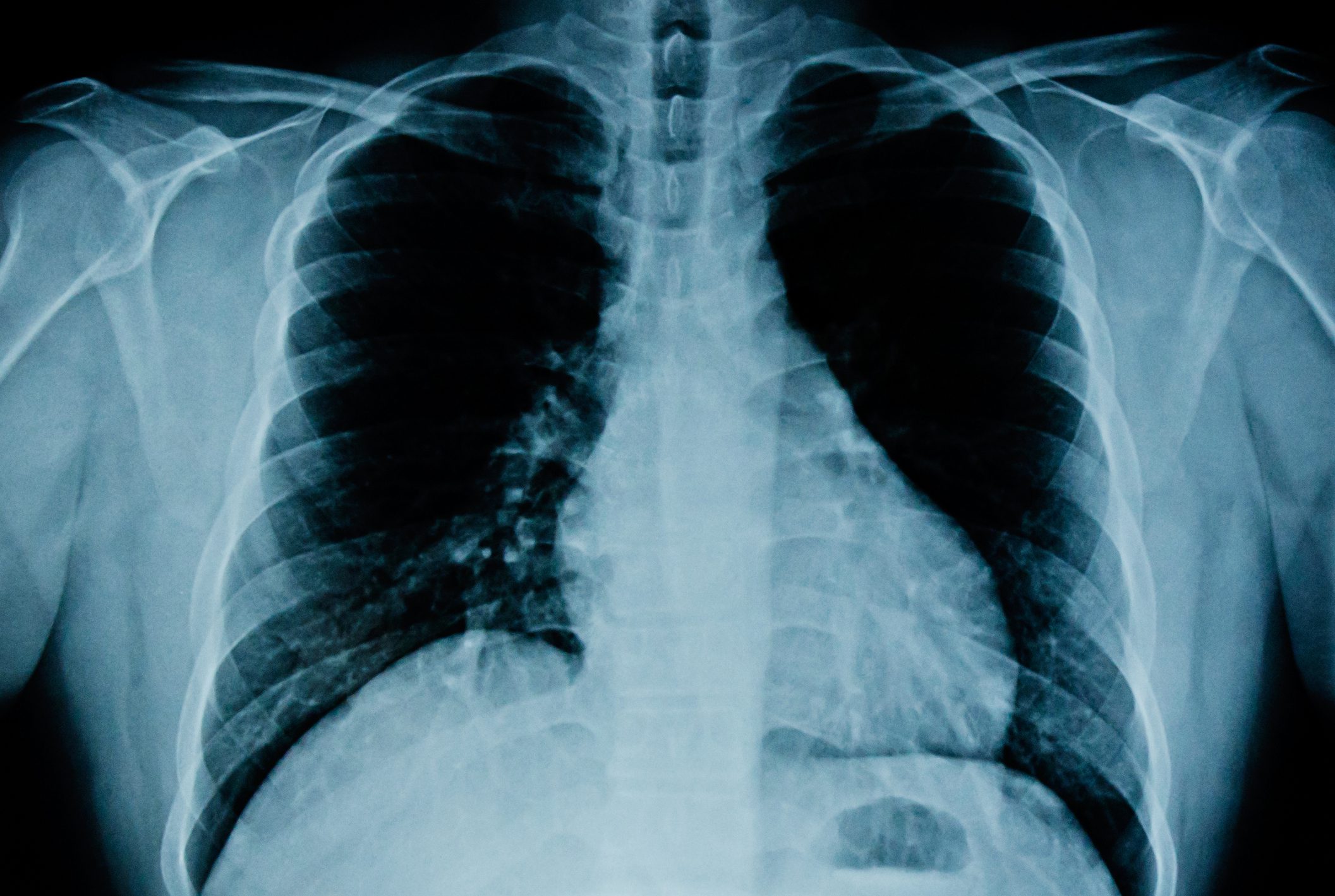

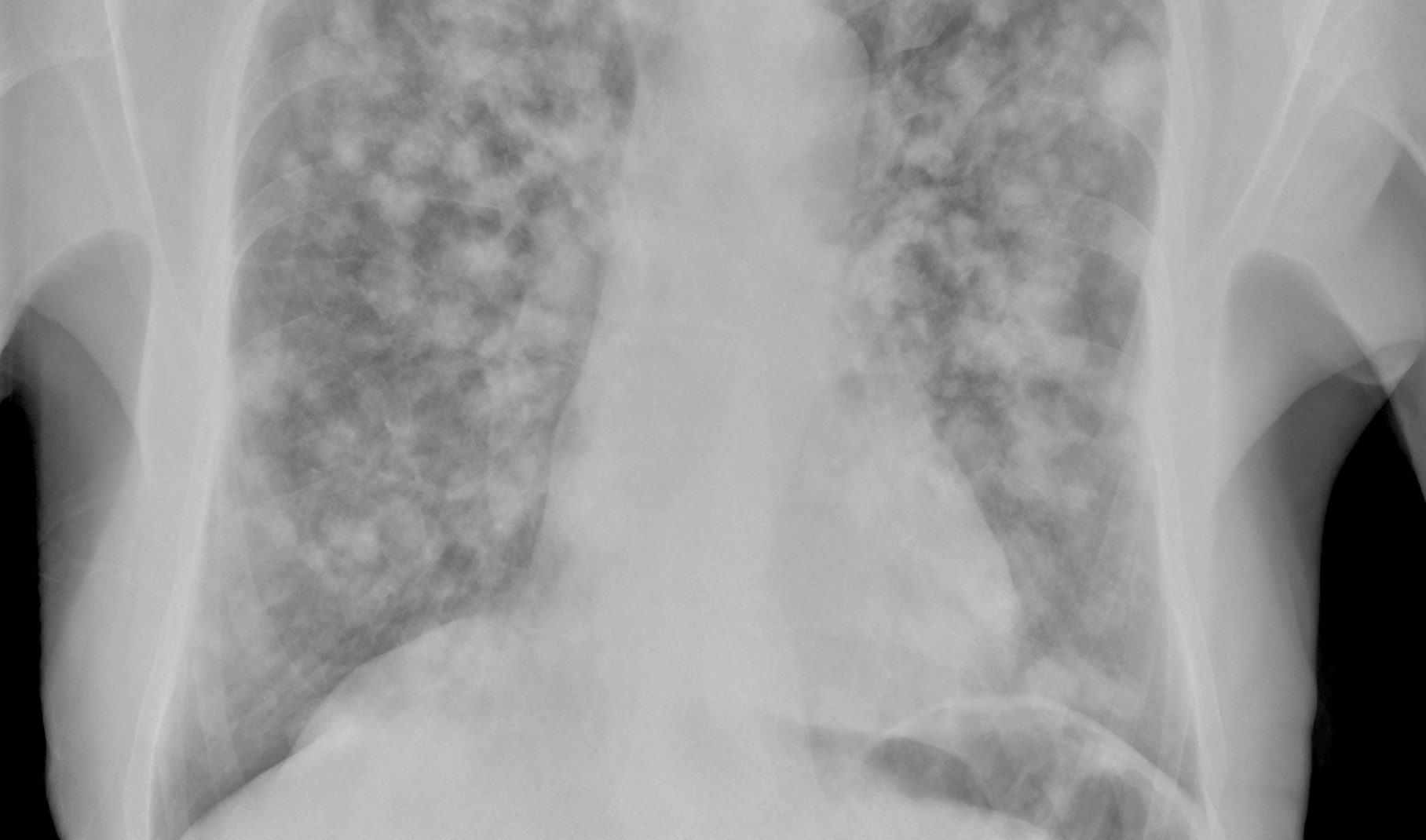

Disease severity and progression, as well as the presence of comorbidities, may also affect treatment adherence and functioning, including recent pulmonary exacerbations and/or hospitalizations [10–12], relationship to disease progression [30,31], and physical comorbidities [32] and psychological comorbidities [33].

In addition, there are a variety of factors that may impact treatment adherence that are related to the specific treatments and interventions in which patients with CF participate. These include perceived benefits and complexity of treatment, as well as frequency and duration of treatments. For example, patients may also experience fatigue, exhaustion or burnout from daily treatments. In addition, the treatments can cause stress and inconvenience in daily life [34]. Furthermore, adverse effects and polypharmacy are also barriers to treatment adherence [35].

The health care system and CF team members interact with patients in a variety of ways to support treatment adherence both in daily life and at key transition points. Critical to the functioning of CF teams and their support of treatment adherence are the knowledge, awareness, and communication skills of the team [8]. The way the health care system is organized in terms of multidisciplinary team support [36] and therapy adherence protocols and assessments [37,38] also affects patient adherence. In addition, while digital monitoring tools can support adherence [39], adherence to these tools also depends on factors such as patient preference [40], which must be considered.

Furthermore, there are social and financial resources available to the patient that can support treatment adherence. Social resources include educational level [20] and aspects of the family environment. [41]. Financial resources include household income [42] and prescription drug coverage [43]. These factors may also affect aspects of the previous four areas.

Treatment adherence measurement

Accurate measurement of treatment adherence is very important, as the data serves as the basis for any intervention with patients. Different and unreliable measurement methods (e.g., self-report, bottle counting, and prescription recording) are important factors responsible for inconsistency in reported treatment adherence rates. Even in cases where patient understanding of the disease and treatment plan is satisfactory, accurate measurement of treatment adherence rates (expressed as a percentage of prescription) is methodologically problematic.

Therefore, it is critical for CF teams concerned about their patients’ adherence to therapy to follow current best practice guidelines. These include (i) measuring knowledge of the disease and treatment, understanding of the disease and treatment plan, and factors that block treatment adherence at both the individual and family levels, (ii) the preparation of comprehensive treatment plans with written copies for patients and parents; and (iii) triangulating data by using at least two assessment modalities (e.g., daily diary and electronic monitoring) and then examining agreement between two or more outcomes, with electronic data taking precedence [44,45].

Important key stages in the process of support

Working with patients to improve treatment adherence consists of six key phases. These phases must occur as part of routine clinic and ward visits.

Build collaborative relationship: Interventions start with conversations. For a CF team to effectively discuss potentially sensitive issues with a patient, there must be a sense of commitment and connection between the two. In the National Health Service (NHS) in England, for example, the most common written complaint in 2020 was about communications [46]. In CF treatment, the importance of optimized communication between physicians and individuals and families living with CF is well known, especially with regard to daily care, treatment adherence, and psychosocial concerns. In a study published in 2020, CF clinicians emphasized the need for resources and training to better engage their patients in high-priority areas such as social, psychological, and economic challenges; preparing for the transition to adulthood; and maintaining daily care. In addition, advanced communication skills that promote trust building have been identified as extremely valuable [47].

The foundation of good communication is listening. Listening and understanding help shape consultations to get the most clinical information out of patients. It is important to recognize that good listening is not a passive process; it involves more than just sitting still. Active listening leads patients to become actively involved in their healthcare and creates a true collaborative relationship between them and their healthcare professionals. It also leads to a more honest and ultimately useful dialogue. In turn, an optimal reaction consists of “OARZ” [48]:

Open questions: These questions cannot be answered with a single word or sentence. For example, instead of asking, “Do you like to drink?” the question might be, “What feelings do you have about drinking?”

Affirmations: Support and comment on a patient’s strengths, motivation, intentions, and progress. It is very important to maintain morale, especially if you want the patient to take a difficult step, such as continuing treatment, where self-confidence is an important factor.

Reflective listening: A physician can demonstrate that he or she has heard and understood the patient by reflecting back what the patient has expressed. There are different ways to do this, from the simple (just reproduce what was said, maybe change a few words) to the more complex (reproduce the meaning of what was said).

Summaries: It can be very useful to summarize what has been said. The summary provides a good pause in the conversation before moving on in another direction. Summarizing different strands can also be very telling, such as the different ways someone has talked about their concerns.

In a collaborative relationship, CF teams can have an open and honest discussion with patients. Along the way, information and education are provided, and the patient is empowered to make decisions that affect him or her with support. During such discussions, patients feel they have some control over their treatment plan. They are informed about CF and its treatment and can then negotiate with their team from an informed perspective.

Assess: Good assessment does not focus only on current treatment adherence, although this is important. The assessment should include all factors that may influence treatment adherence. In general, a complete assessment should identify current behaviors and knowledge, explore current beliefs and resources, explore the role of the patient’s family/friends/partners, explore barriers/supporters, and explore problem situations in detail.

Negotiation: The principles of true collaboration lead to open and honest conversations, conveying key messages, and listening to and understanding an actively engaged patient. This is because discussions and negotiations about treatment plans can only take place effectively within the context of a collaborative relationship. Although CF teams have clinical responsibility and cannot openly condone reduced/modified therapy, this position must be balanced with a realistic assessment of what a patient will actually do when discharged from an inpatient stay or when leaving the clinic. In many cases, it will be necessary to discuss the issue with the patient.

Motivate: The thought of change is in the air, but the decision is, of course, up to the patient. However, we know that it is always easier for individuals to stay with the same old thing, especially if the change they are seeking is difficult and means having to deal with some scary or troubling thoughts about their illness. So how should a CF team member try to counteract the bias against maintaining the status quo? The CF team can address this issue by helping patients explore all thoughts and feelings about the decision. Ultimately, this involves the confrontation of incompatible or contradictory beliefs.

Active listening must be used to identify discrepancies between patients’ thoughts and behaviors. In this way, it is possible to assess how important patients consider change (i.e., improvement in their adherence to treatment) to be and how confident they are in achieving it.

Plan: Once you’ve decided to make a change, having a plan can make the difference between success and failure. The first step in the planning phase is to set goals. It is tempting to set vague goals, but if the goals are not clear, change can prove problematic and success is impossible to judge. The best way to set goals is therefore to formulate the goals “SMART” (SMART = Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound). The “SMART” formula allows goals to be clearly defined, measured with an acceptable degree of certainty, realistic, related to the patient’s goals, and achieved within a reasonable time frame. It is worth noting that it is usually best to start with small, preliminary steps to gain the patient’s trust.

Whenever someone starts a change, it is very likely that they will encounter obstacles. These obstacles can delay, stall, or completely prevent the change process. A useful strategy to help patients overcome barriers is to implement implementation plans. Research has shown that the use of this simple technique can have a moderate to large effect on target achievement rates [49–51]. Implementation plans help patients create an action plan for any barriers to change. Most importantly, write down the obstacle and solution before attempting the change. The solution is then well rehearsed before the problem occurs.

Positive reinforcement can be used effectively to help a patient plan for change. It is advisable for a CF team member to spend some time determining what patients might do to reward themselves if they are successful in bringing about change. It should be clear what it is and when this reward can be granted. Useful to document this. It is important that the rewards are actually perceived, because this associates the behavior with the reward. The most effective rewards are psychological because they make the patient feel in control and do the right thing, and they make them feel proud and confident. On the other hand, most also respond to material rewards.

Monitoring and review: the final phase is about monitoring what happens after a patient initiates a change. It is important to take time to review progress, reflect on successes, and revise the plan if it is not working. Above all, morale should be kept high and the focus should be on change. Change is not easy and often requires several attempts to be successful.

The motivational interviewing (MI)

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an intervention developed for situations where a patient needs to make a behavior change but is unsure or even dismissive of the idea. It is based on the idea that the first step in any counseling is to start a conversation. Subsequently, certain strategies are used to steer this conversation toward change.

The background is in the treatment of people with alcohol problems, where the traditional approach was to confront the person with the consequences of their drinking problem, assuming that they would not get better unless they admitted they had a problem. As a rule, those affected defended themselves by denying that they had a problem. It was then tempting for counselors to blame the patient and imply that he had “no willpower” and “no motivation.”

Psychologist Bill Miller addressed this issue in depth and, contrary to prevailing opinion, suggested that denial should not be viewed as a lack of willpower or motivation to solve the problem, but rather that this outcome should be seen as a product of the situation in the counseling session. Miller went on to suggest a number of ways a consultant might try to avoid confrontation, laying the groundwork for MI [52]. MI was further developed in collaboration with Stephen Rollnick, a clinical psychologist working in the field of addiction in the United Kingdom. Rollnick recognized the relevance of this approach to the field of physical health, particularly lifestyle change and subsequent treatment adherence. A directional, client-centered counseling style that elicits behavior change by helping clients explore and resolve ambivalence [53].

Main principles of MI

Although MI has its roots in clinical practice, it is now clear that the main principles of MI have a very long history. They can be summarized in six general principles.

Principle 1: Patients should not be told what to do. Even when a member of the CF team gives the right advice, most patients don’t comply when they are simply told what to do. When people feel they have no choice, they feel a real need not to do what they have been told – to prove they still have free will. This phenomenon is described by the “reactance theory” developed by Jack Brehm in 1966.

Principle 2: Listen. If a member of the CF team is unable to listen to patients and engage them in conversation, patients are unlikely to change. This part of MI has its roots in patient-centered counseling, proposed by Carl Rogers, who argued that change can be facilitated by giving people therapists who use a nondirective style, who are empathic, sincere in their attempts to understand, warm in their responses, but mainly listen [54].

Principle 3: The patient should tell the CF team member that they need to change. The best thing that can happen is for patients to tell a member of the CF team why they should change. When patients say it themselves, without the CF team member saying it first, it is much more effective. The reasons are also usually stronger. If someone does something because he thinks it is right, he is more likely to carry it out than if he does it to please someone else.

Principle 4: Cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance was proposed by Leon Festinger in 1957 as a feature of situations in which people struggle with a decision to change that makes them uncomfortable. When handled appropriately, it creates momentum toward change. MI refers to and aims to use an understanding of the principles to promote change. When the contrast between the two choices becomes clear, people feel the urge to resolve the conflict by making a choice.

Principle 5: People need to feel safe before they try to change. Even if patients are convinced of the need for change, they are unlikely to try it if they do not feel safe. Worse, they may be depressed when they become aware of their predicament. When self-confidence is high, patients feel confident and have a much greater chance of succeeding. The MI specifically states that morale must be kept high.

Principle 6: Ambivalence is normal. It is normal for people to be unsure of what to do, especially when the decision is difficult or involves a difficult change.

MI strategies

MI has a hands-on focus. The strategies are persuasive rather than compelling, supportive rather than argumentative. The motivational interviewer must proceed with a strong sense of purpose, clear strategies and skills to pursue that purpose, and a sense of timing to intervene in a special way at crucial moments. The four main strategies of MI are [55] as follows: Expressing empathy through reflective listening, developing the discrepancy between goals/values and current behavior, adjusting to resistance rather than confronting it directly, supporting selfadvocacy, and increasing self-confidence.

Express empathy through reflective listening: The CF team’s first goal when working with a patient is to open the conversation. Even when the CF team is concerned about a patient, especially when behavior change is urgently needed, actions taken quickly can come to naught if reflective listening is not done. It doesn’t matter if a health care provider has access to the best medical treatments available; if patients don’t show up for an appointment, they can’t benefit. This is a difficult situation, but in most cases it is more important to engage with patients so that patients are more likely to respond to what is said and come back.

Conversations can be conducted on two levels. At the first rather superficial level, interactions are polite and formal. On the second deeper level, you take time to find out what is going on with the patient and how they are feeling. The first level is typical of most counseling sessions in the clinic. In the vast majority of cases, this is also sufficient. However, sometimes the first level is not enough to gain a good understanding of the patient’s problems and help them. The second level describes the conversations people have with those they are close to and trust. If there is a significant problem that is interfering with treatment adherence, it is unlikely to surface in the clinic unless the conversation goes to a deeper level.

Most people are skilled at having conversations on a deeper level. In the clinic, CF team members typically adopt a way of interacting that keeps things at a more superficial level. In this way, the CF team members can concentrate very well and use the time effectively. Sometimes, however, physicians need to give themselves permission to use their natural abilities to open a conversation with a patient on a deeper level to help them solve a problem with therapy fidelity.

Developing the discrepancy between goals/values and current behavior: Once the conversation is underway, the CF team member’s role is to help the patient think about change. A team member might wonder if it is necessary to use techniques that focus on change, since the topic of change will likely come up during the conversation with the patient. This is a valid concern, but in situations where change is charged with emotion, such as when the thought of increasing medication intake triggers thoughts about the consequences of illness and nonadherence, a person’s natural tendency is usually to try not to think about it.

In this context, the CF team’s role is to “level the playing field,” i.e., to ensure that there is an honest discussion about the consequences of changing or not changing. Many techniques that can be helpful in this situation aim to raise awareness of the problem and focus on the discrepancy between beliefs and goals, what patients would like to do (or what they think they should do) and what they actually do.

CF team members can achieve this goal through summaries. With approval, a team member may also include objective assessments such as test scores or diaries. One technique used in addiction therapy is for the healthcare professional to keep a “drinking diary” with the patient: The healthcare professional shares a sheet of paper with the patient on which the days are marked, and together they enter the amount of alcohol that the patient believes he or she drank in a given period of time. The healthcare professional then asks the patient to add up the amounts and asks if they find the total surprising. This technique can be adapted for many other situations, including treatment adherence.

MI involves the use of scaling questions. These focus on the two things that together make up “readiness”: Importance (“I know I should change”) and Confidence (“I know I can change”). The CF team should ask about the importance. How important does the patient think it is for them to change at this time, on a scale of 0 to 10, followed by a similar question about confidence in being able to change.

Visual analog scales can be very useful; they immediately focus the conversation on the here and now and can highlight potential barriers to change long before they interrupt the work. After asking the patient to rate their importance and confidence, the CF team member can ask, “What would it take for you to achieve X?” where X is a slightly higher rating than the one the patient gave.

In some ways, MI can be thought of as a decision-making tool for those deciding whether or not to change a behavior. The metaphor of the scales is useful; the physician’s job is to help patients weigh the pros and cons of change and encourage them to be open and honest when advocating for change. A useful technique is to make the advantages and disadvantages clear using a decision matrix (Table 2) [1] that can be completed with the patient, listing the benefits and costs of retention and change. This grid can be used to discuss the benefits of not switching and the costs of switching. The grid also makes it possible to discuss the benefits of change. It is suggested to move through the grid by first discussing the benefits of retention, then the costs of retention, then the costs of change, and finally the benefits of change.

Be prepared for resistance rather than confronting it head on: When the topic of change is under discussion, the CF team must be prepared for some resistance. This is an understandable and common reaction. Avoiding confrontation can reduce resistance, but not eliminate it completely. An important factor is that a CF team member pays attention to the words used. After some practice, it is usually easy for a team member to recognize words that indicate a patient is thinking about change and words that indicate a patient is not doing so or is resisting. Examples of resistance or status quo conversations include arguing, interrupting, denying, and ignoring.

Research shows that strong change talk, especially toward the end of a session, is associated with subsequent change. The CF team must pay attention to elements summarized in the acronym “DARN” [56]: Desire, Ability, Reason, and Need. However, a CF team member may also face resistance instead of DARN words. Poor treatment adherence may also be intentional, although this may not be explicit. A patient may be aware of the need for change but be too fearful to consider it as an option. In such cases, after a good relationship has been established, a team member needs to talk to the patient about the problematic behavior. This should be addressed openly as long as it does not tell the patient what to do. Once the conversation begins, a CF team member is likely to be confronted with some old familiar thoughts and phrases that represent resistance to change. This is to be expected; it is a difficult topic that the patient has probably dealt with several times.

Dealing with this resistance is one of the most useful skills the CF team can develop. Some resistance is a feature of many counseling sessions. After all, few patients like to go to a hospital to be told about things they have to do, and resistance to the idea of a long-term, drastic treatment method is perfectly understandable. It is important for the CF team to ensure that resistance does not prematurely end the discussion about change. Most people’s natural reaction to expressing resistance is to disagree, to try to persuade them, or conversely, to drop the subject altogether. What is common, but not helpful, in this case is for a member of the CF team to respond by trying to convince the patient that they are in the wrong. Clinicians need to avoid the “righting reflex.” In clinical situations, this tendency can be very strong. Unfortunately, when indulged, it almost always leads to unhelpful answers.

“Rolling with resistance” is the term used in MI to describe the act of not responding with conviction, but dodging an argument and furthering the conversation. MI suggests that the CF team should recognize that ambivalence toward a decision that leads to some resistance to change is completely normal. When a CF team member does this, the resistance immediately decreases. Alternatively, the CF team member can use reframing and reflective listening to promote discussion and provide the patient with alternatives. The most important principles for dealing with resistance are as follows: Resistance should not be responded to with confrontation, statements should be rephrased, empathy and reflective listening should be used, ambivalence should be recognized as normal.

Encourage self advocacy and increase self-confidence: when a patient is committed to making a change, a lack of confidence in their abilities can lead to great frustration. He now knows he needs to change, but doesn’t feel able to. In the worst case, this can increase the level of suffering. MI therefore explicitly aims to build confidence and self-efficacy. Even if a patient has decided to make a change, there are usually many ways to achieve it.

A central principle of MI is therefore that individuals take responsibility for their own actions. This is important if change is to be firmly established, but can be difficult in the clinical setting, especially when the patient’s best interests are paramount. However, it is also important to remember that behavior change is usually short-lived unless the patient takes responsibility for his or her decision to change behavior. Respect for the patient helps to increase self-esteem and can facilitate discussion about the real goal of behavior change.

When discussing goals, the CF team can use many techniques to increase the patient’s self-efficacy and chances of success. One technique is to look for past successes. When a patient is in a bad mood or anxious, they can often see past events from a very negative perspective. Reframing these thoughts can be helpful. When discussing practical considerations for behavior change, the CF team can use techniques to encourage creativity in the process, such as problem solving and brainstorming. It is also important for CF team members to be realistic and build bridges from the therapy session into real life; thus, a team member should set smaller rather than larger goals. If patients wish, they can bring people to the session who may be important in implementing their behavior change, such as friends or relatives. Using a simple goal-strategy-goal formula can also be helpful. Writing down these goals makes a difference; they serve as reminders and encourage a greater commitment to change. Sometimes patients also need practical help, such as acquiring skills that the CF team can teach them or learning a new skill.

Take-Home Messages

- Adherence to therapy is required to achieve optimal outcomes in CF; however, suboptimal adherence is a known problem

in CF patients. - Adherence to treatment is influenced by a number of factors, including the patient’s environment, individual characteristics, and behavior and understanding toward treatment and illness.

- Motivational interviewing can be used to bring about behavior change in patients who show resistance.

- Clinicians and CF teams can use motivational interviewing techniques to probe patients’ beliefs and increase their motivation to change.

Literature:

- CF CARE: The management of suboptimal adherence with motivational interviewing (MI). Available at: www.cfcare.net/sites/default/files/file/2021/09/Adherence_and_its_management_booklet-en.pdf.

- Burgel PR, Bellis G, Oleson HV, et al: Future trends in cystic fibrosis demography in 34 European countries. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 133-141.

- Lopes-Pacheco M: CFTR modulators: The changing face of cystic fibrosis in the era of precision medicine. Front Pharmacol 2020; 10: 1662.

- Sawicki GS, Tiddens H: Managing treatment complexity in cystic fibrosis: challenges and opportunities. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012; 47: 523-533.

- Sawicki GS, Ren CL, Konstan MW, et al: Treatment complexity in cystic fibrosis: trends over time and associations with site-specific outcomes. J Cyst Fibros 2013; 12: 461-467.

- Duff AJA, Abbott J, Cowperthwaite C, et al: Depression and anxiety in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis in the UK: A cross-sectional study. J Cyst Fibros 2014; 13: 745-753.

- Bregnballe V, Schiøtz PO, Boisen KA, et al: Barriers to adherence in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: A questionnaire study in young patients and their parents. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011; 5: 507-515.

- Duff AJA, Latchford GJ: Motivational interviewing for adherence problems in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010; 45: 211-220.

- White H, Shaw N, Denman S, et al: Variation in lung function as a marker of adherence to oral and inhaled medication in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1600987.

- Eakin MN, Riekert KA. The impact of medication adherence on lung health outcomes in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013; 19: 687-691.

- Mikesell CL, Kempainen RR, Laguna TA, et al: Objective measurement of adherence to out-patient airway clearance therapy by high-frequency chest wall compression in cystic fibrosis. Respir Care 2017; 62: 920-927.

- Quittner AL, Zhang J, Marynchenko M, et al: Pulmonary medication adherence and health-care use in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2014; 146: 142-151.

- Thee S, Stahl M, Fischer R, et al: A multi-center, randomized, controlled trial on coaching and telemonitoring in patients with cystic fibrosis: conneCT CF. BMC Pulm Med 2021; 21: 131.

- Eakin MN, Bilderback A, Boyle MP, et al: Longitudinal association between medication adherence and lung health in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011; 10:258-264.

- Briesacher BA, Quittner AL, Saiman L, et al: Adherence with tobramycin inhaled solution and health care utilization. BMC Pulm Med 2011; 11: 5.

- Muther EF, Polineni D, Sawicki GS: Overcoming psychosocial challenges in cystic fibrosis: promoting resilience. Pediatr Pulmonol 2018; 53: S86-S92.

- Pakhale S, Baron J, Armstrong M, et al: Lost in translation? How adults living with Cystic Fibrosis understand treatment recommendations from their healthcare providers, and the impact on adherence to therapy. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 1319-1324.

- Ohn M, Fitzgerald DA: Question 12: What do you consider when discussing treatment adherence in patients with cystic fibrosis? Paediatr Respir Rev. 2018; 25: 33-36.

- Zanni RL, Sembrano EU, Du DT, et al: The impact of re-education of airway clearance techniques (REACT) on adherence and pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. BMJ Qual Saf 2014; 23(suppl 1): i50-55.

- Flores JS, Teixeira FÂ, Rovedder PM, et al: Adherence to airway clearance therapies by adult cystic fibrosis patients. Respir Care 2013; 58: 279-285.

- Arden MA, Drabble S, O’Cathain A, et al: Adherence to medication in adults with Cystic Fibrosis: An investigation using objective adherence data and the Theoretical Domains Framework. Br J Health Psychol 2019; 24: 357-380.

- Happ MB, Hoffman LA, Higgins LW, et al: Parent and child perceptions of a self-regulated, home-based exercise program for children with cystic fibrosis. Nurs Res 2013; 62: 305-314.

- Keyte R, Egan H, Mantzios M: An exploration into knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward risky health behaviors in a paediatric cystic fibrosis population. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2019; 13: DOI:1179548419849427.

- Nicolais CJ, Bernstein R, Saez-Flores E, et al: Identifying factors that Facilitate Treatment Adherence in Cystic Fibrosis: Qualitative analyses of interviews with parents and adolescents. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019; 26: 530-540.

- Quittner AL, Abbott J, Georgiopoulos AM, et al: International Committee on Mental Health in Cystic Fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus statements for screening and treating depression and anxiety. Thorax 2016; 71: 26-34.

- Prieur MG, Christon LM, Mueller A, et al: Promoting emotional wellness in children with cystic fibrosis, Part I: Child and family resilience. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021; 56:(suppl 1): S97-106.

- Hogan A, Bonney MA, Brien JA, et al: Factors affecting nebulised medicine adherence in adult patients with cystic fibrosis: A qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm 2015; 37: 86-93.

- Oddleifson DA, Sawicki GS: Adherence and recursive perception among young adults with cystic fibrosis. Anthropol Med 2017; 24: 65-80.

- Helms SW, Dellon EP, Prinstein MJ: Friendship quality and health-related outcomes among adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Psychol 2015; 40: 349-358.

- Lomas P: Enhancing adherence to inhaled therapies in cystic fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2014; 8: 39-47.

- Dziuban EJ, Saab-Abazeed L, Chaudhry SR, et al: Identifying barriers to treatment adherence and related attitudinal patterns in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010; 45: 450-458.

- Ronan NJ, Elborn JS, Plant BJ: Current and emerging comorbidities in cystic fibrosis. Press Med. 2017; 46: e125-e138.

- Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Tanny T, Breuer O, et al: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2018; 17(2): 281-285.

- Sawicki GS, Goss CH: Tackling the increasing complexity of CF care. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015; 50(suppl 40): S74-79.

- Narayanan S, Mainz JG, Gala S, et al: Adherence to therapies in cystic fibrosis: A targeted literature review. Expert Rev Respir Med 2017; 11: 129-145.

- Zobell JT, Schwab E, Collingridge DS, et al: Impact of pharmacy services on cystic fibrosis medication adherence. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017; 52: 1006-1012.

- Riekert KA, Eakin MN, Bilderback A, et al: Opportunities for cystic fibrosis care teams to support treatment adherence. J Cyst Fibros 2015; 14:142-148.

- Santuzzi CH, Liberato FMG, Morau SAC, et al: Adherence and barriers to general and respiratory exercises in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020; 55: 2646-2652.

- Calthorpe RJ, Smith S, Gathercole K, et al: Using digital technology for home monitoring, adherence and self-management in cystic fibrosis: a state-of-the-art review. Thorax 2020; 75:72-77.

- Calthorpe RJ, Smith SJ, Rowbotham NJ, et al: What effective ways of motivation, support and technologies help people with cystic fibrosis improve and sustain adherence to treatment? BMJ Open Respir Res 2020;7: e000601.

- Everhart RS, Fiese BH, Smyth JM, et al: Family functioning and treatment adherence in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol 2014; 27: 82-86.

- Oates GR, Stepanikova I, Gamble S, et al: Adherence to airway clearance therapy in pediatric cystic fibrosis: socioeconomic factors and respiratory outcomes. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015; 50: 1244-1252.

- Li SS, Hayes D Jr, Tobias JD, et al: Health insurance and use of recommended routine care in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Respir J 2018; 12: 1981-1988.

- Quittner AL, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, et al: Evidence-based assessment of adherence to medical treatments in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol 2008; 33: 916-936.

- NICE. Clinical guideline: CG76. Medicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence (January 2009). Available at:

www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76. Accessed July 2021. - NHS Digital. Data on Written Complaints in the NHS. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/data-on-written-complaints-in-the-nhs/2020-21-quarter-1-and-quarter-2. Accessed July 2021.

- Cooley L, Hudson J, Potter E, et al: Clinical communication preferences in cystic fibrosis and strategies to optimize care. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020; 55: 948-958.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 1991.

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P: Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 2006; 38: 69-119.

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P: Implementation intentions. Health behavior constructs: Theory, measurement and research. Cancer Control and Population Sciences. National Institutes of Health; 2008. Available at: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/constructs/goal_ intent_attain.pdf. Accessed July 2021.

- Gollwitzer PM: Weakness of the will: Is a quick fix possible? Mot Emot 2014; 38: 305-322.

- Miller WR; Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother 1983; 11: 147-172.

- Rollnick S, Miller WR: What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother 1995; 23:325-334.

- Rogers C: Empathic: An unappreciated way of being. Couns Psychol 1975; 5: 2-10.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 1991.

- Miller WR: Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. 2004. Available at: www.motivationalinterviewing.org/sites/default/files/MItheory.ppt. Accessed July 2021.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(10): 6-14