Burnout with leading symptom exhaustion is usually associated with an excessive demand due to chronic stress factors in the professional context. However, clinical experience and intensive research in recent years show that the overload underlying a burnout process can also result from the parenting role.

Burnout with leading symptom exhaustion is usually associated with an excessive demand due to chronic stress factors in the professional context. However, clinical experience and intensive research (www.burnoutparental.com/international-consortium) in recent years show that the overload underlying a burnout process can also result from the parenting role. Parent burnout occurs when there is a persistent mismatch between perceived demands and personal resources in parental responsibilities. The importance of parental burnout is particularly high, as the well-being of the children and the partner resp. of the partner is directly affected and the parental role, unlike a job, cannot be terminated.

Typically, the beginning of the development of parent burnout shows an increasing exhaustion, from which an emotional distance to the child can develop. The affected parent experiences dissatisfaction with his or her role as a parent and a discrepancy with the previous parental self-ideal [1]. The aforementioned emotional distance from the child should be classified as a “red flag”, as it negatively influences the further course of burnout and can be associated with potentially dysfunctional behaviors towards the child [2].

Diagnostic classification

A burnout process can lead to a mental illness, especially depression, anxiety disorder or somatoform disorder. Physical symptoms and exacerbations of physical ailments may also increase as a result of stress processing disorders. According to ICD-10, the resulting illness is diagnosed, e.g. a depressive episode. To specify the burnout context, a Z diagnosis can be added (Z73 “Being burned out”, in the category “Problems related to difficulties in coping with life”). In the new ICD-11, burnout is exclusively related to the work context under “factors that may affect health” – despite the available scientific evidence on parent burnout – which is controversially discussed by experts [3].

Parent burnout must be diagnostically distinguished from maternal postpartum depression, which occurs after childbirth and is primarily due to hormonal changes. Parent burnout does not occur until later in parenthood [4]. The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA) with 23 questions is available for the diagnosis of parental burnout [5]. It has been translated into many languages and can be used free of charge via www.burnoutparental.com/instruments-and-materials.

Demographics

Point prevalence is at least 3% of parents in Western industrialized countries such as Switzerland. Twice as many women as men are affected [5–7]. However, the consequences in men are more often severe, especially the risk for escape and suicidal ideation is increased. Parent burnout occurs significantly more often in our individualized societies than in collectively organized societies [8]. Women, single parents, parents of young children, parents with multiple children, and parents of children with chronic conditions and special needs (ADHD, Asperger’s, etc.) are particularly affected. Demographic factors have a much smaller impact on the etiology of parent burnout than individual factors [9].

Risk factors

Parents with perfectionism and poor emotion and stress management skills are especially at risk for developing parent burnout. Inconsistent parenting practices and lack of routines in the organization of family life also increase the risk. Parents with difficulties in the couple relationship are also at risk, especially if they disagree on parenting issues, do not support each other, do not recognize or even denigrate their partner. A high parenting burden also exists in the absence of support from extended family or friends. Little available time for individual or partner leisure activities, recreation, and “quality time” with children – time devoted to family relationship maintenance independent of daily tasks – are other factors that increase the risk for parent burnout [10].

Therapy approach

While there is a good body of scientific data on the demographics, symptomatology, and risk and protective factors of parent burnout, there is little empirical research on treatment, particularly no randomized-controlled trials with follow-up. Based on the multimodal, scientifically tested therapy program “SymBalance” for burnout treatment by Ballweg et al. and the evaluated model for balancing resources and risks in parent burnout by Mikolajczak & Roskam, the following treatment model was developed and established in clinical practice [11,12]:

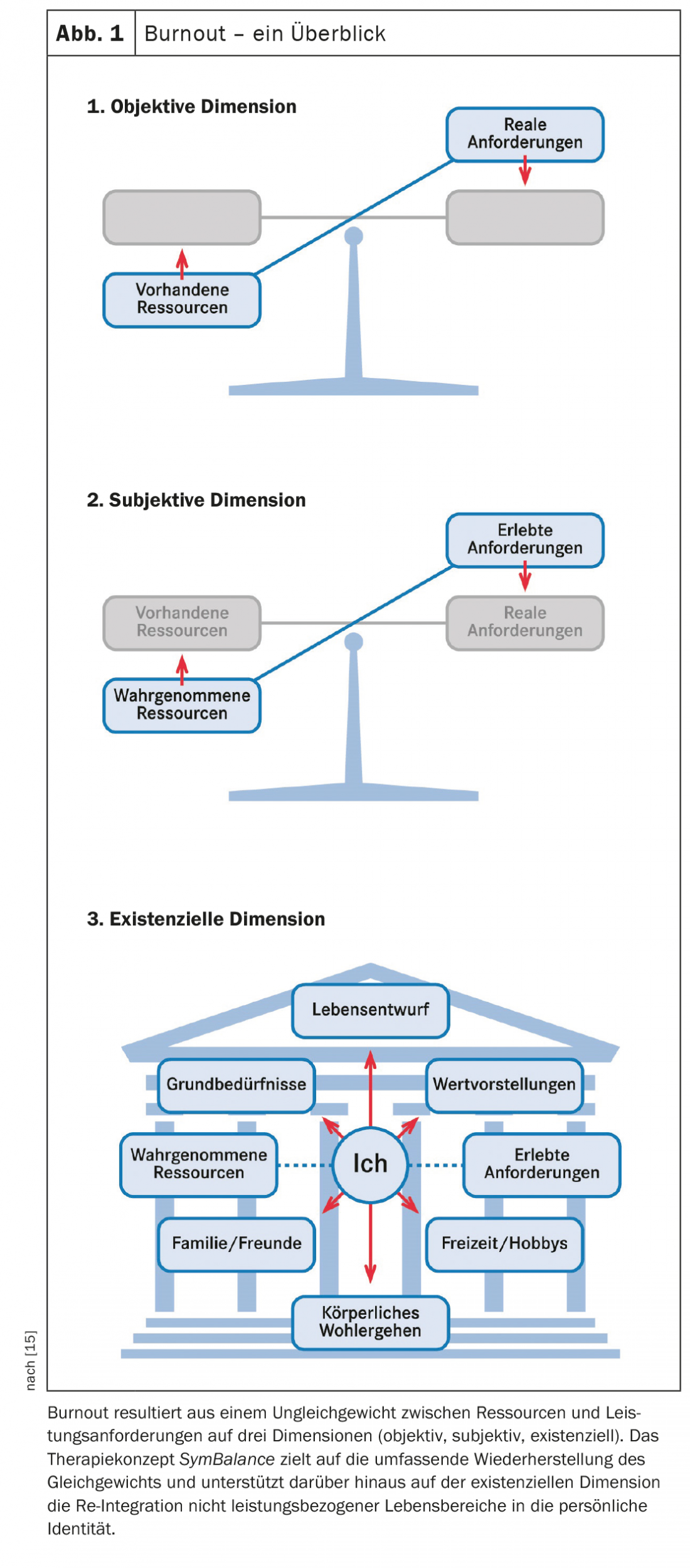

The therapy approach includes three stages: 1. recognition and initial interventions, 2. clarification, 3. coping. The goal of the therapy approach is to strengthen parental self-efficacy through the psychotherapeutic process. It is an individualized approach that assesses personal resources, stress factors as well as dysfunctional patterns and derives therapeutic interventions from them. Systemic factors of couple and family interaction are also considered. The established model of Effort-Reward Imbalance by Siegrist, which describes how an imbalance of effort and reward can lead to the development of stress, is used as a basis, whereby three different dimensions (objective, subjective and existential) are distinguished [11,13]. The distinction is important because parent burnout in particular can only be partially explained by objective situations of excessive demands in the family. Much more important is the imbalance on the subjective level, which results on the one hand from too high expectations and demands on oneself and on the other hand from subjectively inaccessible, although basically available, resources. The existential level considers how a persistent imbalance affects the person’s self-concept (Fig. 1). The psychotherapeutic approach should be complemented in clinical work by social counseling and support, assistance with parenting issues, approaches to regeneration and promotion of the ability to relax, and – if necessary – by drug treatment. The involvement of the partner is almost always indicated.

Therapy level 1 – Diagnostics and first interventions

If there is evidence of parent burnout, specific stress factors and symptoms can be assessed by questionnaire [5]. The discussion and psychoeducational processing of the questionnaire helps patients to understand their problem, which can provide emotional relief, reduce anxiety and improve compliance in the further course of treatment. In the evaluation of the questionnaire, the extent of emotional distance should be particularly considered and additionally explored. In order to ensure the care of the children and to relieve the domestic situation, social support options should be addressed at an early stage and organized if necessary. Antidepressant or sleep-inhibiting medication should be considered and established in the presence of moderate depression or manifest sleep disorders. After clarification of the situation and initial measures for stabilization, a recommendation is made for further treatment – depending on the severity and complexity – in the outpatient or also in the inpatient setting.

Therapy level 2 – Clarification

The therapy concept provides for clarifying the stressful situation of the parental role on three levels: objective, subjective and existential. The aim is to work together with the patient or the to develop an individual etiological model for the patient in order to derive appropriate therapeutic interventions. The following points can be used as a guide for this:

Objective dimension

- family daily routine

- Tasks and division of tasks in the family as partners

- own professional tasks and resulting conflicts of objectives with family demands

- Analysis of the family system

- Exposure of role stereotypes with consideration of gender issues

- Opportunities for balance/recreational activities alone or as a couple.

- specific challenges in education

Subjective dimension

- Typical cognitions and emotions related to the parenting role (especially stress-inducing imperatives on oneself and associated feelings of guilt, anger, fear, or helplessness).

- Identification of emotionally stressful situations and conflicts

- Parenting styles (with special attention to consistency or inconsistency) and extent of cooperation in the sense of co-parenting

- Satisfaction with the partnership relationship

- Personality traits (especially perfectionistic, emotionally unstable traits, increased need for control, and a tendency toward self-sacrifice).

Existential dimension

- ideal mother-image/father-image, also in connection with one’s own biography (personal background incl. one’s own attachment experiences as a child, role models and anti-models, grasping discrepancies in the sense of unfulfilled expectations of oneself)

- unfulfilled idea and expectation of the child/children (inner image of a “desired child”)

- implicit family and societal expectations (differentiation between self-expectations and expectations of others)

- “Identity” and role conceptions outside of parenthood.

Particularly relevant on the existential level is a clarification of biographically shaped schemas that impair or even prevent the experience of positive attachment experiences with the child [14]. These include, above all, avoidance schemas such as the fear of mistakes, failure and weakness or the fear of helplessness and loss of control. If avoidance schemes play a role, it is necessary to record as precisely as possible through which concrete behavioral strategies they are realized and how this limits the desire to experience closeness and affection for the child. The results of the analyses at the objective and subjective levels are also included.

Just as important as the clarification of problems and deficits is the recording of resources and resilience factors on all three levels. These include, on the one hand, motivational readiness in the sense of approach goals aligned with one’s own life plan or a positive family value system (existential level), on the other hand, competencies in dealing with oneself, one’s own thoughts and feelings, which are helpful for self-regulation (subjective level) and, finally, abilities to cope with crises and conflicts (objective level), especially if they are significant in the current family context. Non-specific resilience factors such as reliable social relationships or regular leisure activities (objective level) are also relevant.

Therapy level 3 – Coping

In the actual process of change and coping, therapy goals and associated interventions are derived at all three levels according to the individually developed thematic areas of the etiology model. Overarching goals are to reduce parental stressors, develop resources for coping with stress in the family context, and promote self-esteem and self-efficacy in the parenting role. Typical topics on the different dimensions are:

Objective dimension

- Changes in everyday family life, workload, daily routines and task assignment

- Dealing with conflicting goals between family and career

- Promotion of parental own time

- Enabling social support

Subjective dimension

- Improvement of emotion regulation and modification of mental patterns, especially perfectionism and black-and-white thinking.

- Learning and integrating relaxation methods and mindfulness techniques.

- Reflection and change of parenting methods for the sake of consistency and co-parenting.

- Promote child-parent relationship

– Valuing the quality of the present moment in being with the children

– Promoting positive interactions with the child and enabling resonant experiences in the interaction. - Promote couple relationship, improve satisfaction in the partnership

Existential dimension

- revise ideal mother/father image (biography work) and work through own parent-child conflicts

– Reduce exaggerated expectations of children; say goodbye to the inner image of the “desired child” and accept the “real child”.

– Consider parents’ attachment experiences and stressful experiences in their own childhoods.

– Reflection of personal values and revealing discrepancies in their realization in everyday family life

– consciously give life a direction - Working on conflict schemas, strengthening the approach component (attachment), weakening the avoidance component (failure, weakness, loss of control).

Take-Home Messages

- A burnout process can also arise in the context of parenthood – with far-reaching consequences for the entire family system.

- The main risks for the development of burnout are individual factors, especially perfectionism and problems in emotion and stress regulation.

- The focus of treatment is psychotherapy oriented on three dimensions to restore parental self-efficacy.

Literature:

- Roskam I, Brianda ME, Mikolajczak M: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Front Psychol 2018; 9:758.

- Blanchard MA, Roskam I, Mikolajczak M, Heeren A: A network approach to parental burnout. Child Abuse Negl 2021; 111: 104826. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104826

- Hillert A, Albrecht A, Voderholzer U: The Burnout Phenomenon: A Résumé After More Than 15,000 Scientific Publications. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 519237. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.519237

- Scola C, Le Vigouroux S: Différences entre burn-out parental, dépression du post-partum et dépression majeure [Differences between parental burnout and postpartum depression]. Soins Pediatr Pueric. 2021; 42(323): 22-24. French. doi: 10.1016/j.spp.2021.09.005

- Roskam I, Brianda ME, Mikolajczak M (2018): A Step Forward in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Parental Burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology.

- Roskam I, Aguiar J, Akgun E, et al: Parental Burnout Around the Globe: a 42-Country Study. Affec Sci 2, 58-79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4

- Roskam I, Mikolajczak M: Gender Differences in the Nature, Antecedents and Consequences of Parental Burnout. Sex Roles 83, 485-498 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01121-5

- Super CM, Harkness S: Research on parental burnout across cultures: Steps toward global understanding. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2020; 2020(174): 185-192.

- Vigouroux SL, Scola C. Differences in Parental Burnout: Influence of Demographic Factors and Personality of Parents and Children. Front Psychol. 2018; 9:887. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00887

- Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ, Roskam I: Beyond Job Burnout: Parental Burnout! Trends Cogn Sci 2021; 25(5): 333-336.

- Ballweg T, Seeher C, Tschitsaz A, et al: SymBalace: a theory-based integrative therapy concept for the treatment of burnout. Swiss Arch Neurol Psychiatr 2013; 164(5): 170-177.

- Mikolajczak M, Roskam I (2018): A Theoretical and Clinical Framework for Parental Burnout: The Balance Between Risks and Resources (BR²). Frontiers in Psychology.

- Siegrist: The effort-reward imbalance model. In: Occupational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 2000; 15(1): 83-87.

- Grawe K: Neuropsychotherapy. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2004.

- www.symbalance.ch

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(5): 8-11.